Calamity at Every Turn

To travel the Pony Express, riders had to brave apocalyptic storms, raging rivers, snow-choked mountain passes, and some of the most desolate, beautiful country on earth. To honor the sun-dried memory of those foolhardy horsemen, we dispatched Will Grant and a 16-year-old cowboy prodigy to ride 350 miles in a hurry.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

It took us 60 miles and two days on the to lose our horses. That morning, the four of us had hauled out of Granger, Wyoming, near the Utah state line, with a tailwind blowing scarves of dust before our cavvy of nine horses. We were rich in horseflesh but shy on experience, and we took our horses’ quiet demeanor as evidence that all nine had settled into the ride. We were mistaken.

That night’s camp lay on the east bank of the Green River. We rode in from the west, with the setting sun at our backs, and found the water running dark and dangerous. We crossed over the river on Highway 28, where the road narrowed to a two-lane bridge with no real shoulders and a rarely observed 70-mile-per-hour speed limit. Once across, we made ourselves at home, about a mile from the road in an oasis of grass and mosquitoes. We failed to notice, though, that our access road didn’t have a cattle guard—a grid of pipes set into the ground to prevent livestock from venturing where they shouldn’t.

for your iPhone to listen to more longform titles.

An hour after we’d turned the horses loose to graze, I was on a low bench above camp trying to get a better view of the river. Just then, three of the horses lifted their heads from the stream where they’d been drinking and began to vector worryingly toward the highway. Two of them wore hobbles, leather straps connecting a horse’s front feet to restrict its movement, provided the animal doesn’t jerk free of it. Which is exactly what these two did—and then broke into an easy trot headed for the blacktop.

I quickly gave chase, thinking I could get in front of them, when I remembered something my old horse-training mentor had told me: “T��� first thing your horses will do once they’ve rested up from the day’s work is trot right back in the direction they’d come.” Losing horses in wide-open country could be the kind of problem that takes days to sort out. Or cost an unsuspecting driver their life, should they fail to see three errant horses straddling the double-yellow line. I expected to hear squealing brakes and the dull thud of vehicle on flesh at any moment.

But help was on the way. Quirt Rice, a 16-year-old kid riding with us, saw what was happening, grabbed his bridle, caught one of his horses from where it grazed, and swung up onto its back without a saddle. He wore just his red union suit, jeans, a black hat, and boots. He spurred the small horse into a gallop and took off for the highway.

Quirt is the closest thing to a cowboy prodigy I’ve ever been around. He came on lofty recommendation from the old man who mentored me in Texas. “T��� kid’s got more talent with a horse than any young man to come through my barn,” he said. Now Quirt flew past in a blur, leaning low over his gelding’s neck and pounding down the dirt road.

The three outlaws crossed the slippery cement bridge with their heads high and the percussion of their footfalls ringing out in the humid evening air. Quirt followed closely behind them with the determined expression of a cowboy hell-bent on doing his job.

The herd quitters peeled off the highway to the south and broke into a gallop as they passed an Oregon Trail interpretive kiosk. Quirt swung wide, his horse taking long jumps as it cleared the sagebrush, badger holes, and irrigation ditches, and then all of them disappeared from view.

I was on the shoulder of the highway, struggling to see the chase, when a white Nissan Altima came roaring toward me. At the same time, the headlights of a car appeared from the other direction, and my girlfriend, Claire, stood in the middle of the road, waving her arms for the cars to slow down. Which they did, just as Quirt brought the horses back to the highway.

With a whoop and holler he pushed them up the road, in front of the stopped cars, and headed back to camp at a trot. All four animals were covered with sweat, their nostrils flaring and veins standing out on their necks. “Well, that was exciting,” Quirt said. “I haven’t ridden bareback that much in a long time.”

There were 290 miles of trail ahead of us. It looked like we’d earn every one of them.

When the Pony Express launched on April 3, 1860, it was the most impressive mail service in the world. The top speed of a human in those days was on the back of a galloping horse, and the Pony Express did everything it could to maintain that velocity across 2,000 miles of wilderness between Missouri and California. Prior to the service’s inception, the fastest way to get a letter to the West Coast was a 21-day stagecoach journey through the deserts of Texas and what had recently become the American Southwest.

That wasn’t nearly fast enough for the 380,000 people living in California, which had become a state in 1850. People there rallied for speedier communication, hungry for news of the political turmoil between the northern and southern states. In January 1860, Congress approved the hiring of a frontier freighting company—Russell, Majors, and Waddell, based in Leavenworth, Kansas—to set up a mail relay 1,966 miles between the end of the railroad at St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento via the Mormon settlement at Salt Lake in Utah. Off the ponies flew later that spring, beating out the relays between 157 stations spaced 15 to 20 miles apart. Riders were recruited primarily from local ranches, because they were good with horses and knew the country.

From the start, the proponents of the Pony Express—including a Unionist California senator—intended it to be a testament to the viability of a central mail route, one that stayed north of Mason and Dixon’s famous survey line. The riders proved them right by cutting the previous delivery time in half, delivering messages in just ten days.

But fast travel over wild country had its challenges. Though just one mail pouch was lost in the running—some reports say two—there were plenty of mishaps. On the last section of the first westbound mail package, a horse tripped, fell, and broke its rider’s leg. When a Wells Fargo stagecoach passed on the same trail, a company stage agent volunteered to finish the ride. He blazed into Sacramento to much fanfare, though the mail was 90 minutes late.

In a separate incident, a rider galloping out of San Francisco ran into an ox sleeping in the road and was crushed by his horse in the resulting fall; he died a short time later. Another rider became lost in a snowstorm in Nebraska and froze to death. Yet another died in a river crossing. One Express horse fell and broke its neck, leaving the rider to transport the mail afoot. During the Pony’s most famous act—carrying Lincoln’s inaugural address—a rider was shot through the arm and jaw by arrows, lost several teeth, and finished out the eight-hour, 120-mile relay through the Nevada desert badly wounded.

If all that sounds a bit like frontier snake oil, it’s because most of what we know about the Pony Express is shrouded in myth and whiskey. One of its earliest documentarians, William Lightfoot Visscher, a half-drunk Chicago journalist who rubbed elbows with the likes of Buffalo Bill, wrote an early account of the mail service in his 1908 book .

Critics charge that the book wants for accuracy, footnotes, and a bibliography, but Visscher’s contribution comes mainly in the form of first-person accounts. “It is a marvel that the pony boys were not all killed,” one former rider wrote Visscher. “What I consider my most narrow escape from death was being shot at by a lot of fool emigrants, who, when I took them to task about it on my return trip, excused themselves by saying, ‘We thought you was an Indian.’ ”

In addition to trigger-happy Yankees, the riders faced stampeding bison, flooded rivers, and long hauls on exhausted horses. There were scrapes with outlaws and horse thieves. The Indians could generally be outrun by the grain-fed Express horses, but the weather could not. A spill meant plowing into the ground at up to 30 miles per hour.

One hundred and fifty-seven years after the Pony launched, much of the trail is still rideable, though few attempt it. Today, reenactors keep the trail warm in an annual re-ride, galloping out 15-to-20-mile legs of the route. But I didn’t want to ride 15 miles. I wanted to see the trail at a slower pace over a longer distance—eating alkali dust and dragging a string of packhorses along the way. I wanted to know what it felt like to take in the horizon through the ears of a horse. I wanted to ride in June, when the days are long and the grass is tall, and to travel across the basins of intermountain Wyoming, where the land is public and the people are few. It would be a lesson in the history of the American West—part empirical grit and rawhide, part 19th-century lore. But first I needed a good hand. Quirt fit the bill.

Quirt was born in Rapid City, South Dakota, in 2000. Today he stands near to six feet tall, with light red, short-cropped hair and traces of a ginger beard clinging to his chin. Like most horsemen, his brawn lies in his forearms, grip, and legs. He began riding soon after he started eating solid food. When he was seven, he had a horse drop dead underneath him while herding a cow down a dirt road. His mother was in a pickup just behind. The incident spooked him from horses, but a year later his grandfather bought him a gentle brown pony named Coco.

“At first, Grandpa just led me around the corral, like I was a little kid or something and couldn’t even ride my own horse,” he said. “Both of my grandpas and my dad really helped me.”

At eight, Quirt trained a pair of oxen to pull a wagon. At 12, he was breaking colts, peeling broncs, and riding anything with four legs that would take a saddle. He’s since worked with horse trainers in Texas and Wisconsin, been hired as a cowboy in California and Wyoming, and put together his own herd of 26 cows. When I asked if he was game for the Pony Express ride, he just nodded in the affirmative. I asked if he had any dietary restrictions.

“I don’t much like vegetables, definitely not raw tomatoes,” he said. “Meat and taters pretty much works for me.”

We’d go with a photographer, Nate Bressler, and my girlfriend, Claire Antoszewski, a physician’s assistant in a hospital emergency room. We’d have nine horses and a support trailer—driven by a family friend of Quirt’s, Dale Deuter—that would meet us at designated camps most nights, to ensure sufficient feed and water for the horses. A handful of ranchers and landowners knew we’d be coming through and had offered us corrals, pastures, and access to the trail.

Help was on the way. Quirt Rice, a 16-year-old kid riding with us, saw what was happening, grabbed his bridle, caught one of his horses from where it grazed, and swung up onto its back without a saddle.

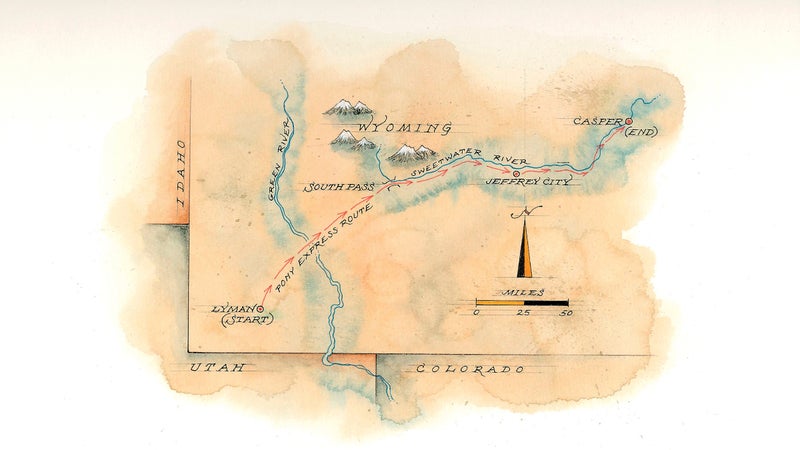

Our roughly 350-mile route along the Pony Express trail was almost entirely on Bureau of Land Management acreage. From Lyman, Wyoming, about 20 miles from the Utah line, we’d travel west to east across the Church Buttes gas field and the richest soda-ash deposit in the world, to the Green River. We’d skirt the dry watershed of the Great Divide Basin to the north and top out on the Continental Divide at South Pass, about 100 miles north of the Wyoming-Utah-Colorado border. From there we’d follow the Sweetwater River’s meandering valley past historic ranches and Mormon sites to the North Platte River. Fifty miles of near waterless trail would then bring us to Poison Spider Creek outside Casper, the end of our trail.

“That’s a hell of a long haul across there,” said Shawn McCoy, who bought and sold cattle before he opened the burger joint where we dined two nights before we hit the trail. “T���re’s basically nothing out there but rattlesnakes.”

It wasn’t the rattlesnakes that worried me: it was traveling overland with a herd of horses that would break for home when turned loose, come up with sore feet after a day on the rocks, and sink themselves in mudholes while carrying a pack. Dialing in our routines and caring for the horses pushed aside all other concerns. We’d ride four while the other five carried our supplies. Every one of them we rode came into the trip physically fit, able to handle a string of 30-mile days over rough country—but that didn’t mean they knew how to travel.

Ensuring our horses’ welfare and minimizing their workload were the priorities. “We want to avoid wrecks,” Quirt said. “We need our horses sound.”

Our most dreaded hours were the hot ones in the late afternoon, when the sun sapped the animals’ energy and the miles felt long. To avoid that, we started early. “Get up. We’re burning daylight,” Quirt said practically every morning.

At 4:30 A.M., we boiled water for coffee and oatmeal. Quirt needed eggs and meat for breakfast, so he and Nate ate while Claire packed the food that she would eat an hour down the trail. By first light, we’d loaded the panniers and saddlebags. Quirt would wrangle the herd—each night we kept at least two horses tied up in camp and turned the others loose to graze, two with bells around their necks to help us find them in the morning—and then we’d hit the trail.

On the first day, Nate asked, “When do we stop for lunch?”

“We don’t,” Quirt said, without turning around in his saddle.

“I was thinking we might have a picnic in the shade of some trees,” said Claire.

“We don’t stop. Can’t when you have packhorses,” Quirt said. “And there ain’t no trees out here anyway.”

The tallest features of the landscape for most of our journey were fence posts and pronghorn antelope. The sage and grass hills rolled by like slow midocean waves. The horizon hung below our stirrups, and snowy mountains sat low and purple in the distance. Our progress ticked off in half-mile segments, measured along much of the trail by concrete pylons standing four feet high, marked for the trails that ran there, usually the Oregon, California, Mormon Pioneer, and Pony Express routes.

The thoroughfares, which are a few miles wide in places, saw their first surge of emigrants in the 1830s, when settlers headed for Oregon came through walking beside their teams of oxen. Three hundred thousand gold seekers bound for California, along with Mormon settlers from the late 1840s into the 1850s, shared the same ruts. But of all the 19th-century traffic, the fastest men on the trail were the riders of the Pony Express.

Eighty men rode for the company, each carrying the mail for an average of 100 miles. Over that distance, a rider changed horses six or seven times, swapping his tired mount for a fresh one at each station. Sam Jobe, an Express rider in Wyoming, was quoted saying he could cover 21 miles in an hour. I mentioned that to Quirt as we tugged on the packhorses at a rate of three miles an hour. All he said was, “That’d be nice.”

One reason Quirt would have been a good rider for the Pony Express—other than that he’s skinny as a rail and rides like a Comanche—is that he’s always in a hurry. Stopping to smell the roses is fine by him, just make it quick. “When he was nine, Quirt made a very detailed list of what he wanted in life,” his mom told me when she showed up two-thirds of the way through the trip to drop off his guitar, the one piece of equipment he’d forgotten at home. His wish list included a pickup truck, a welder, and cows, among other western essentials. “He’s pretty much got it all by this point.”

He also has a weakness for sweets. He’s never had a Coca-Cola—he doesn’t like carbonated drinks—but he loves cookies. For all our generous provisioning of meat and potatoes, we hadn’t brought enough of them to satisfy demand. Scottish shortbread or gluten-free, it didn’t matter to Quirt—he’d eat a handful and then shove a few in his pocket (or under his hat) for later. The morning we left the Green River, Quirt reminded us that there was an ice cream shop in Farson, 28 miles ahead. “Let’s go get some ice cream,” he said, and whipped his horse over its hindquarters with his bridle reins.

We rode from camp at an easy gallop under a low ceiling of clouds. Halfway to Farson, the cavvy needed a drink, so we dropped into the valley of the Big Sandy River. The runoff from record snowfall in the Wind River Mountains had blown out every river and creek in the watershed. For two weeks prior to the trip, the National Weather Service issued flood warnings for the area nearly every day.

As a result, there was no shortage of water along our route, but it wasn’t always easy to get to. Mudholes and quicksand were everywhere. Cutbanks ran dark, smooth, and deep. On the edge of the 50-foot-wide Big Sandy, we scouted for a firm approach to the stream. Quirt didn’t like what he saw—the river had flooded its banks and ran over the sod, tall grass waving in the current—so he stood back. Nate, meanwhile, edged his horse up to the water while we watched his test.

During the Pony’s most famous act—carrying Lincoln’s inaugural address—a rider was shot through the arm and jaw by arrows, lost several teeth, and finished out the eight-hour, 120-mile relay through the Nevada desert badly wounded.

Nate’s horse, Brushy, was big—probably 900 pounds. When he lowered his head to drink, the submerged bank collapsed beneath him, and the horse slowly slid into the river. As the pair went down, Nate lifted his camera bag off his chest and scrambled for the bank. He crawled out, swearing like a Navy chief. Brushy plunged and splashed and came out wet. Nate’s cameras were fine, but his lower half was soaked through, and he had to empty his boots of river water.

“We gotta get a photo of this,” he said, giving his camera to Claire. He balanced one arm on my shoulder and poured a disappointingly small amount of water from his boot. Twenty miles of riding in wet jeans, though, left an impression on his butt and inner thighs: Nate’s saddle sores would only barely heal by journey’s end.

More than halfway into the trip, we arrived at the biggest town along our route: Jeffrey City, Wyoming, population 58. A family friend of Quirt’s, Molly Meyer, had secured an old roping arena where we could take a layover day. It would be our only time off, the idea being that the horses could fatten up and relax—though we’d been told to expect insects.

“Town isn’t much, just an intersection,” Molly had told me before we started. “T��� bar may or may not have food. Depends on who’s cooking. Also, I’m warning you, the mosquitoes can be bad. The place is kind of famous for them.”

She wasn’t lying. The bugs there would be enough to incite panic in an Alaskan caribou. Riding in, I ran a hand down my horse’s neck and pulled away a bloody fistful of insects. To the people who live there, the mosquitoes are hardly worth talking about. To the uninitiated or unprotected, they are maddening.

We’d made about 250 miles in seven days of travel. Other than a few mishaps, everyone was in good shape. Except we were hungry. The would be the only restaurant we’d encounter on the trail, so we left the horses to swish their tails while we went for cold beers and the possibility of chicken-fried steak. The bar had several big-game heads on the walls, as well as a few bovine skulls, at least two of which still had decomposing flesh on them. The jukebox ate several dollars’ worth of quarters but never quite seemed to play the chosen songs. Halfway through dinner, a very tired-looking man in a plaid shirt walked out of an unlit recess that contained a pool table as though he’d been sleeping back there. Which, we later learned, he was.

Of all the unforeseen circumstances we encountered, the compatibility of our group was the most welcome. Through stress and near disaster, we were amiable. Despite the navigational issues and discord over organizing the kitchen, we tightened into a familial bunch. As the days and miles passed, Nate came to think of Quirt as a younger brother.

“I’m coming to South Dakota to work for you, Quirt,” he said as we bent elbows at the Split Rock. “You can be the boss. I’ll park my camper in your yard, and I can do the whole ranch-hand thing.”

Thirty-six hours in Jeffrey City just about dried up our supply of Deet, and we figured our horses had let enough blood to the damn mosquitoes. At dawn we left our dust hanging in the air and headed east for Mormon territory, passing a landscape of discarded alcohol containers and bottles of urine fermenting in the sun along the shoulder of Highway 287. We knew that the ranchers, who I had contacted before the trip, would welcome us and our horses. The Mormons we weren’t so sure about.

In 1856, two parties of Mormon emigrants, both from Europe, left Iowa City with all they possessed loaded into handcarts. Too poor to afford livestock, the 1,100 pioneers resorted to pulling oversize wheelbarrows made of uncured wood. The carts fell apart, and early-winter storms found the Mormons stuck along the Sweetwater River at Devil’s Gate. By the time they reached Salt Lake, more than 200 of them had died of exposure and starvation.

Today the church maintains an extensive interpretive site along the trail. We rode through the front gate of the Sun Ranch visitor center just after 3 P.M. and were ushered into the old ranch house by Sister Judy, the missionary who would give us a tour. In one room of the house, she pointed to an Evans rifle over the fireplace. Buffalo Bill Cody had given it to the ranch’s owner, who, Sister Judy said, taught the famous westerner the frontier skills he would later popularize in his Wild West Show.

Buffalo Bill had little fear of exaggerating. He liked to say that he’d made the longest relay of any Pony rider—384 miles—when he was 14. It never happened. Though he lied about that experience, he did a lasting service to the Pony Express by including a depiction of it in his show.

Believe everything you read about the Pony and you might think that the riders straddled winged Pegasus himself, that they carried the very flag of Manifest Destiny as they galloped over the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada. Anyone who came close to the route or its riders seemed to fall under its romantic spell.

Though the Pony played a high-profile role in history—even the papers in Europe noted that it carried the news of Lincoln’s election in record time—it was a short-lived enterprise. Eighteen months into its tenure, the telegraph connected Missouri to California and the Pony was finished, having operated at a loss from its inception to the day it folded in October 1861.

“It did not involve more than 150 round trips,” wrote William Banning, who in 1928 published the superb Six Horses, about stagecoaching, freighting, and passenger conveyance in the developing West. “It did not cover a full nineteen months. Like a belated fragment of a storm it came and was gone. Yet the fact remains: a more glamorous contribution to our historic West than that of this ephemeral Pony would be difficult to name.”

“Hold your horses,” Quirt yelled on the shoulder of the highway. I wheeled my horse to see him pointing his .22 autoloader pistol at a buzzing rattlesnake in a cattle guard. For all the times that his gun came out, I never saw him draw it; I’d just turn and he’d be ready to shoot something. He never fired a round during the trip, but it’s a necessary part of any overland kit: a way to humanely put down injured livestock. To me it was yet another example of Quirt’s preparedness and my reliance on him and his gear.

He nearly always rode at the front of our column. As a pathfinder, Quirt was invaluable. He could see a gate in a fence several miles away that I could barely make out with binoculars. A whistle would stop him, and we’d look at the map or unpack a sandwich. As we rode, we talked about other adventures we had in mind. We’d round up a herd of mustangs, Quirt said, spend a week or two gentling them, and then drive the bunch right through downtown Rapid City, South Dakota, to the sale barn. We’d walk away with some easy money.

Like a lot of what Quirt does, the mustang scheme was a moneymaking idea. He knows the value of a dollar better than most adults, and he isn’t the type to let a nickel pass without at least swinging his rope at it.

“Last winter I raised four bottle calves on five goats,” he said, explaining how a gallon of milk per day from each of the goats was sufficient to raise the calves. “A mother cow can cost $4,000 per head, but I got five goats for $1,000, and they give better milk.”

Quirt had no shortage of knowledge about the hardscrabble business of ranching: Never buy a cow with pink udders, he said, because the sun reflecting off the snow will burn her skin and you’ll spend all spring rubbing oil on her. Narrow-shouldered bulls are the best. Through his business, Bar S Livestock, he sells calves and horses—including some of these in our string.

One reason Quirt would have been a good rider for the Pony Express—other than that he’s skinny as a rail and rides like a Comanche—is that he’s always in a hurry. Stopping to smell the roses is fine by him, just make it quick.

“T��� e sets the futures board for almost everyone in the cattle business, so we’re all dealing with the same market,” Quirt said, turning in his saddle. “But I got a guy in Scottsbluff, Nebraska, treats me good, gives me four or five cents back on the pound.”

To reach our final camp at Willow Spring, we covered 28 miles of unbroken sagebrush flats. We’d come about 325 miles in ten days. For the past two, one of Quirt’s horses, called Lunchbox, had been unwell. Named for the fact that he could be trusted to carry the food on pack trips, Lunchbox was 15 years old and the best-trained horse in our cavvy. Though we’d given the horse a break from carrying a rider or supplies for two days, we decided to shuttle him to Willow Spring in the trailer, to allow him an additional day of rest. Quirt was anxious to see him at camp.

That night, Lunchbox drank a little water and grazed but was lackluster and lethargic. At 1:30 A.M., Claire and I woke to the sound of the horse breathing heavily just outside our tent. He strained to draw a breath, grunting and moaning with the labor of his lungs. Claire woke up Quirt, and he gave the horse some painkillers and led him outside camp. At 2:15, I heard Lunchbox stumble through the tall grass toward our tent. He was moaning loudly. Then, in a violent fall of resignation, he threw himself down in the center of camp.

Quirt jumped out of his bedroll and held the horse’s head in his lap. Lunchbox had a quick seizure, kicked his legs a few times, and then lay still in the arms of the cowboy who loved him. Quirt sobbed quietly a few times. Claire sat beside him with her arm on his shoulder. I sat in my tent looking out at Quirt, Claire, and the dark form of Lunchbox. Sleep came that night only by the mercy of fatigue.

We don’t know why Lunchbox died. He had rested the three days before the night at Willow Spring, and his vital signs checked out normal. We don’t think he was overworked; the trail had been mostly level, and our pace had been steady and deliberate. After the trip, I called G. Marvin Beeman, an 84-year-old veterinarian in Littleton, Colorado, who has practiced large-animal medicine for 60 years.

Beeman agreed that the horse didn’t show signs of being overworked. Instead, there was likely some underlying condition that reared up doing our trip. “A horse is a wonderful biological machine,” he said, “but sometimes odd things kill them.”

People like Quirt rely on their horses for a day’s work, and it’s a relationship that’s deepened by its rarity. Which is why I still clench my jaw when I look at photographs of Lunchbox.

The next morning we had a quick breakfast over Lunchbox, whose body still lay in the center of camp. Quirt gathered the horses, and we fed them in the rope corral for the last time. “You guys ride on, and I’ll catch up in a few hours,” Quirt said.

Claire, Nate, and I rode out of Willow Spring to leave Quirt and our driver to deal with the carcass. On ranches, dead horses are usually interred via backhoe, while dead cows or sheep are placed on open land to be consumed by ravens, coyotes, and detrivores. A local rancher helped drag Lunchbox to a similar fate.

Quirt, like most people concerned with animal husbandry, confronts the passing of life on a regular basis. As we rode our final miles, he talked about Lunchbox and other horses he’d owned. In five strokes of bad luck, he’d had five horses die on him. The kid’s entitled to his own way of grieving, I thought. He also had his way of keeping Lunchbox in his life: he’d taken the horse’s tail to make a shoo fly that would hang from his saddle, and he’d skinned the horse to make rawhide.

“I’ll make buttons from the hide,” Quirt said. “T���re’s two ways things come back to life: by God and by rawhide.”

We loped our horses into Poison Spider Creek to finish our trail miles, waving our arms and yelling. Save for the loss of Lunchbox, the horses came through in good shape. With a day of rest, all would have been fit to carry on. As for me, I didn’t want the trip to end. I didn’t want a hot shower or clean clothes; I just wanted more of the windswept prairies from the back of my horse.

But after 12 days on the move, we pulled our saddles and sweaty blankets from the animals and let them roll in the tall grass of a hay meadow. We made cocktails and laid about camp all day without ambition, and the next morning we went our own ways.

When I called Quirt three weeks after the trip, he was in high spirits and had hardly been out of the saddle since returning home. He was rolling out of bed at 3 A.M., he said, to beat the heat and save his horses from working under the sun. His five pregnant mares were heavy with babies that would hit the ground any day now. I asked him if he’d ever saddle up for another long trip.

“T��� thing is, back in the days of the Pony Express, their horses were already trail horses. They already knew about being corralled in the ropes in the morning and all that,” he said. “By the time we finished, we were just getting the hang of everything.”

Will Grant () is a correspondent for the magazine. He wrote about searching for gold in Arizona in the March 2015 issue. is an ���ܳٲ��������contributing artist.