A Liar Standing Next to a Hole in the Ground

That's how Mark Twain defined a gold miner. But when our writer heard head-spinning treasure tales from a legendary prospector named Flint Carter, he organized a full-scale expedition into the mountains near Tucson, Arizona. Following a hand-drawn map, the team lit out for the harsh Sonoran Desert hopped up on gold fever in search of the fabled Lost City.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The old prospector was convinced it was gold, but the geologist couldn’t say for sure. Very small knuckles of a yellow mineral attached to cubes of pyrite were in question. Six of us stood around the rusty iron door that served as our camp table and was now piled high with ore and canvas sample bags inked with GPS coordinates. Flint Carter, the prospector, tipped back his cowboy hat, pulled a thin brown cigarillo from the chest pocket of his overalls, and lit it as the sun set over Arizona’s storied Cañada del Oro.

“That right there would make any miner happy,” he said, nodding at the table. He picked up one of the samples and held it to the dusky light. He moved his hand over the rock, covering it in shadow. “If it’s gold, it shines even when it’s shaded.”

Jason Price, a Ph.D. candidate at the California Institute of Technology with seven years of mineral exploration under his belt, including stints with four different gold companies, snickered at the comment.

“The only real way to tell if there’s gold in it is to send it to a lab,” Jason said. I pressed him about the yellow knuckles. “I just don’t know.… We’re dealing with an uncommon suite of minerals.”

Jason flipped open the hand lens that hung around his neck, held a piece of the rock up to his face, and started spewing mineralized gibberish that was hard to follow. I’d worked for Jason years ago as a geological field assistant mapping copper deposits in Alaska, and he was the most trusted rock nerd I knew. That’s why he was here: to be the voice of science and reason. But only a few hours earlier, he was glowing like a Coleman lantern as we bagged samples from the abandoned mine that Flint’s treasure map had (mostly) led us to. We may not have found the walls of gold supposedly at the end of that map, but there was no question that we were now looking at some high-grade rock. As I was about to write as much in my notebook, all hell broke loose.

The lead ropes of our three horses, which were tied to an overhead picket line between two oak trees, got tangled up, and the animals panicked. Paint Bucket’s lead was wrapped around Brownie’s midsection so tight, he looked like a couple of sausage links. As Brownie tried to buck himself free, Paint Bucket’s head took the beating. Cheeseburger cowered for his life at the end of his rope. The commotion sounded like a cavalry had stormed into camp.

By the time I was able to pop all three ropes with my knife, Paint Bucket was bleeding from her right front shin and Brownie had rope burns on his back legs and flanks and a wound on the inside of his right hock. Cheeseburger, bless his heart—the son of a bitch looked traumatized. All three stood with their heads hung low, like they’d just survived the movie War Horse. I was so pissed off I wanted to shoot ’em all.

The only problem with feeding the horses to the buzzards was that we needed a way to get the gold out of the canyon we were camped in. And we needed to get Flint home. At a not-so-hale 67 years old, he was relying on Cheeseburger for a ride to the truck, parked at the top of Tucson’s Mount Lemmon, some four miles up a skeleton trail more suited to goats than horses and men. I hadn’t come all this way to doctor a bunch of nickel horses worth less than the saddles they were carrying. I’d come to find gold. And I was pretty sure we’d done just that.

As the price of gold fluctuates, so does the number of prospectors in the field. Most have long ago been superseded by large corporations like and , but because times are tough and the price has generally been on an upswing, nearly tripling over the past ten years, the number of people panning, hammering, and sluicing for the stuff has been on the rise.

Gold fever has always been high in Arizona. At the turn of the last century, one in five Arizonan workers was involved in the mining industry. In 2013, the state’s Bureau of Land Management office processed 7,326 new mining claims, bringing the total acreage in the state currently being leased to 923,052. That’s the second largest in the country, behind Nevada’s 3.9 million acres.

I hadn't come all this way to doctor a bunch of nickel horses worth less than the saddles they were carrying. I'd come to find gold. And I was pretty sure we'd done just that.

I first showed symptoms of the fever two years ago, when a friend of mine told me that he had a map to a famous 19th-century gold mine outside Phoenix called the Lost Dutchman. I instantly latched onto the idea. But the harder I tried to pin down specifics, the quieter he became. He eventually ceased all communication, and as a last resort I drove to Tucson to find him.

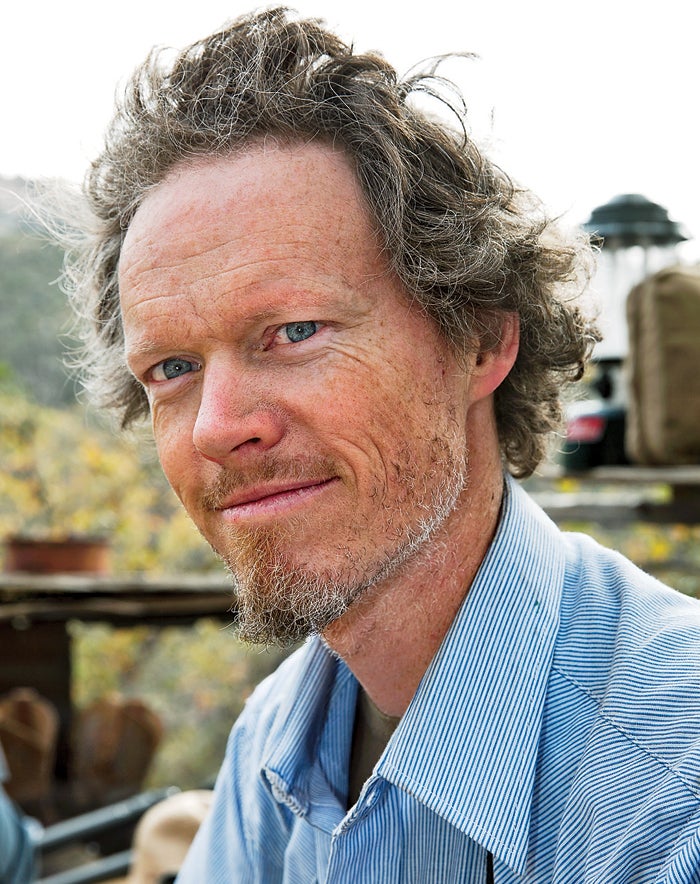

I did manage to get him on the phone, but he said he was too busy to meet for coffee. At last I took the hint and decided to stop badgering him and instead track down a local prospector named Flint Carter, whose name kept popping up in my research about the lost mines of Arizona. Flint is an expert on local mining history and has spent the past 40 years scrambling up and down the Santa Catalina Mountains, working small-scale mining operations with a few pals, making jewelry out of semiprecious metals—including a local white quartz that Flint has dubbed Cody stone—and doing odd jobs.

When we met at a grocery-store deli on the north side of town, he looked the part, wearing a sweat-stained straw cowboy hat with a silver hatband, a western yoked shirt, and shiny black cowboy boots. I told him about my friend and the map.

“Let me tell you something, bud, everybody’s got a map,” he said, working a chicken wing between his molars.

For the rest of the day, as we drove around the area looking at historical sites, Flint smoked Nat Sherman cigarillos and regaled me with stories of Spanish bullion and Apache burial sites. Eventually, he invited me on a trip he was planning to the Lost City, a collection of ruins deep in Cañada del Oro. According to Flint’s version of the legend, the Jesuits enslaved Pima Indians to work a mine near the Lost City. When the Pimas revolted in 1751, the Jesuits supposedly sealed their gold mine with a one-inch-thick iron door. The Mine with the Iron Door and its walls of gold became the subject of , , and treasure hunters. After years of research and many visits to the area, Flint claimed that he now knew where the mine was located.

“I have to go back one last time before I die,” he said to me, his hand on my shoulder. “I need a few good men to go with me. Think about it.”

Later that night, back at my campsite, I considered Flint’s proposition. If I didn’t think there was some kernel of truth to what he’d said, it would have been easy to bow out. And throwing in with him sounded like more fun than walking away. But the old man appeared to be broke—I had to put $5 worth of gas in his car so he could show me an old mission outside town—and ready to keel over at any moment. With every swig of rye whiskey, the situation became clearer to me. Join his expedition? Like hell. It was my expedition now.

A month later we were headed to the Lost City. Six of us made the party: Flint, the man with the plan; Jason, the geologist; Claire Antoszewski, a physician’s assistant and friend of mine whom I’d conscripted for the sole purpose of keeping Flint alive; John Hankla, an old buddy who agreed to help with logistics and labor; Tom Fowlks, the photographer; and myself.

From the top of 9,157-foot Mount Lemmon, not too far from the local ski area, the plan was to ride downhill a few miles into the heart of Cañada del Oro. We’d spend four days working in the vicinity of Oracle Ridge, which has been intermittently mined since the turn of the 19th century, looking for the Mine with the Iron Door (Flint’s main objective) and for highly mineralized, potentially valuable zones of a magma body (Jason’s objective).

The night before we set out, we laid our gear on tarps in the sand at a campsite in . We had hummus, grapes, tins of smoked oysters, and steaks bundled with dry ice; a bazooka-size tube of U.S. Geological Survey quadrangle maps, geologic topos, and Google Earth images; rock hammers, a sledgehammer, ore sample bags, and geologic compasses; two handguns and a flare gun; two boxes of wine and two bottles of liquor; and, specifically for Flint, who on doctor’s orders had quit drinking seven years ago, half an ounce of high-grade Colorado marijuana and five packs of Nat Shermans. And because he told me he’d nearly died of pancreatitis five months ago and appeared to have any number of other undiagnosed ailments, we had a med kit the size of a suitcase, a bundle of prescription drugs, and a hospital-grade, nearly three-foot-tall oxygen tank that looked like the surest way I’d ever seen to blow up a packhorse and burn the state of Arizona to the ground.

Surveying our truck of gear made me wonder about Paint Bucket, Cheeseburger, and Brownie, the three horses I’d rented from a local guest ranch. I told the wrangler there that I was going to do some mellow trail riding, and they hardly looked up for that. I’ve worked as a cowboy and horse trainer and done my share of hauling horses over rough country. From the looks of our cavvy, I knew it would take some hand-holding to get those flatland nags in and out of the canyon.

Group dynamics were also a concern. Hankla can be a tireless worker, which is why I’d brought him on, but as soon as he met Claire, a free spirit who is beautiful and argumentative, he became preoccupied with getting into her sleeping bag and not nearly as useful as a laborer. While this infuriated me, it was a mere annoyance compared with the mounting friction between Flint and Jason, which threatened to derail the expedition before it even started.

“The first time I met him, he insulted me in my own house,” Flint had told me the day before. “I don’t know what they’re teaching him in school, but that kid don’t know shit about mining.”

Jason was equally combative. “What Flint thinks is gold isn’t gold,” he said with a chuckle. “It’s chalcopyrite”—which, to a gold prospector, is fool’s gold. “But he probably won’t like the sound of that.”

My spirits momentarily lifted as we headed into the canyon. The weather was cool and sunny, the horses were fresh, and everyone looked smart in the pearl-snap shirts I’d bought the day before. Plus, the farther we descended, the healthier Flint looked. The mountain air didn’t make him any less cantankerous, though, and he and Jason continued squabbling like adolescents, arguing about everything from the hardness of rocks to which minerals carry gold.

We made camp by early afternoon. An old corrugated-tin cabin sat at the center of the site, and rusty mining equipment—a 1929 Rolls-Royce engine, an old stamp mill for crushing ore, a small candleholder mounted on an iron spike—lay strewn about the scrubby oaks and yuccas. Flint had been coming here since 1978 and claimed it was the site of one of Buffalo Bill’s famous tent camps. After we got everything sorted, Hankla, Tom, and I saddled the horses up and headed back to the trucks to get the remaining half of our gear. By the time we walked into the firelight six hours later, exhausted and covered in sweat, Jason and Flint had settled, and Claire had broken into the wine.

“Flint and I had it out while you guys were gone,” Jason told me.

“Oh yeah? How’d that go?”

“Well, in the end he told me he liked me, so I think it’s OK. You still have your story.”

“Gold, Jason. Gold is what I want.”

Gold in the Santa Catalina Mountains occurs along the mineralized margins of a magma intrusion. About 80 million years ago, a plume of molten lava rose upward from the liquid center toward the surface. The plume intruded the existing limestone and sandstone and cooled before breaching the surface. During the cooling process, minerals—like gold, silver, lead, copper, and zinc—precipitated from the hot liquids in the cracks and fractures of the ancient rock. As erosion scoured and slowly wore down the sedimentary rock to form the mountains we see today, the intrusion and its associated structures outcropped on the surface.

“Historically, Arizona has a lot of gold,” says Jeff Garrett, a mining engineer with the BLM in Phoenix, “but we’ve never had the water to develop the streambeds. Gold needs water, and we’ve never had enough of it.”

The lack of water hasn’t prevented the Flint Carters of the world from prospecting. You probably haven’t seen them. They don’t use established trails or campsites, usually don’t tell anyone where they’re going or what they’re doing, and often end up needing help. “We see their cars parked at the trailhead, and we have absolutely no idea where they are,” Dave Bremson, operations chief of Arizona’s Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office Mountain Rescue team, later told me. “There’s no age limit to this stuff, either,” he added. “We picked up a 90-year-old man who had his own oxygen cylinder with him from home.” That sounded about right, I told him.

Cañada del Oro is littered with mining refuse, and the hillsides are riddled with mines. Maybe it was Jason’s influence or the way Arizona’s harsh sunlight can dash even the longest-held fantasies, but somewhere between my first meeting with Flint and arriving in camp, the focus of the expedition had shifted from a mine with walls of solid gold to something more realistic: an abandoned mine above the Lost City that, according to Flint, had gold-bearing ore on the walls. But before inspecting the mine, Jason first wanted to determine where we were on the magma plume, and the only way to do that was to take measurements of the rock and draw a map. With headlamps, notebooks, and compasses, we started piecing together the geological puzzle. The many adits, or horizontal shafts, would provide us cross-sectional views of the mountain.

“North 60 east on this quartz vein, dipping 84 degrees to the southeast,” Jason said, holding his compass to the white rock. “That’s consistent with what I’d expect. Take a sample of this stuff and label it Flint’s adit number one.”

Flint was skeptical but let Jason work. We climbed the rocky slope above the mines, working higher on the intrusion. Hankla found a rattlesnake, and Jason could hardly walk past a rock without rapping it with his hammer. He liked what he was seeing in the mines: skarn mineralizations, flow-banded granodiorite, possibly some auriferous pyrite.

“Along these weird deposits is where you can get gold. This limonitic clay could run it.”

At a small grassy terrace in an arroyo, Flint motioned me to his side and whispered, “Mark this spot on your GPS. It’s a buried mine, and there’s gold in it.”

I made a waypoint of the location and called it Gold 1. A few minutes later, Jason, Claire, and I stopped to chat.

“Flint says there’s a buried mine shaft here,” Claire said to Jason.

My head nearly exploded. I was immediately angry that Flint had let Claire in on the secret. As far as I was concerned, he and I were partners. Claire had been included in the expedition only in a support role. Jason just laughed at her remark and my reaction.

“I’ve seen quite a few old mine shafts,” he said, walking away, “and that’s not what they look like.”

If my first symptom of the fever was believing Flint about the walls of gold, then my second was being upset that he’d told others about that mine shaft. He may not have any formal geologic training, but he had walked a lot of miles in these hills and had recently helped write a book about Santa Catalinas’ lost treasures. Even Jason had acknowledged Flint’s on-the-ground expertise.

That night in camp, Hankla’s attempts to woo Claire became so pathetic, I briefly considered sabotaging his efforts by bringing up all his ex-girlfriends. Then Claire drank enough mescal that she nearly fell in the fire. More important, Flint finally drew us the map to what we’d come to see: the Mine with the Iron Door. He wasn’t up for the journey himself but claimed that he could practically walk there blindfolded. We’d skirt the valley to the north for a mile or so, walk up an arroyo to the largest rock in the streambed, and then head toward the tallest tree in the valley, where we’d find a spring and the ruins of the Lost City. Uphill and to the south of it was an abandoned mine that had snow white walls of quartz laced with dark red veins of gold-bearing hematite.

“That’s what you’re after,” Flint told Jason and me as we looked at the map. “Bring back as much as you can carry.”

Anyone who thinks he’s immune to the fever should follow a hand-drawn treasure map with a levelheaded geologist like Jason Price. When the geologist’s eyes light up and he tells you that you’re closing in on pay dirt, I’ll be damned if you won’t clamber over rocks and plow through cactus to find the next outcropping. We all did, and we hung on Jason’s observations of the rock like we were scratching lottery tickets.

Side-hilling below the magma body, we moved like a pride of lions en route to hunting grounds. We found the largest boulder in the arroyo and turned south toward the tallest tree in the valley. At its base, a spring leaked into the arroyo. It was all just as Flint had said.

The ruins of the Lost City were two 20-foot-square stone structures that shared a wall. All that remained of the structures were the bottom three feet. The stones, some the size of grapefruits, others the size of basketballs, were loosely chinked with silt that turned to dust when disturbed. The doors faced downhill, looking over the canyon. The ruins were old, but how old? Jesuits? Whatever. I didn’t care. We weren’t here for a documentary.

As soon as we left the Lost City, conditions on the ground no longer jibed with Flint’s instructions. One of the problems with a hand-drawn map is that it doesn’t tell you shit other than where a few odd landmarks are. It wasn’t to scale and didn’t have a compass rose. Once the map became useless, we resorted to geological common sense and Jason’s lead.

When a geologist's eyes light up and he tells you that you're closing in on pay dirt, I'll be damned if you won't clamber over rocks and plow through cactus to find the next outcropping.

We walked up a boulder-filled arroyo, where the rocks were stained turquoise with oxidized copper. Jason cracked a green boulder with his hammer and nodded in approval toward the top of the slope.

“I can see why this stuff would drive a prospector crazy,” he said. “Let’s get underground.”

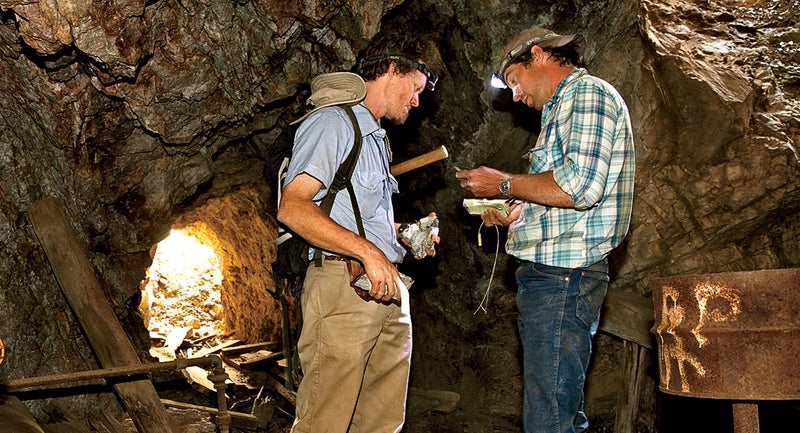

Eventually, we found the mine. The entrance was tight, about 18 inches around. I thought it looked like a good place to run into a rattlesnake; Jason was more worried about a potentially unsafe hairline crack above the entrance. Neither concern gave us too much pause, though, and we pushed our packs in before us and then carefully slid on our backs into the mine.

It was cool and dank inside, about as big as an Amtrak car, and everyone put on eye protection as Jason unsheathed his hammer. Sunlight shafted through a blowhole at the top of the mountain as he began rapping the walls. We walked over a collapse of rubble. I tried not to think about what would happen if the rotting timber that may or may not have been supporting the whole deal collapsed.

The walls showed a spectrum of colors: blues, greens, reds, oranges. Crystals, veins, and lenses ran in one wall and out the other. Quartzite, azurite, epidote, and hematite, according to Jason. Slightly green tremolite asbestos—the only rock in the place safe from Jason’s hammer—grew on the ceiling in elongated fibers. Rusty rails ran along the floor, covered in places with a carbonaceous ooze that looked like horizontal stalactites.

We found no wall of white quartz laced with red hematite, but Jason didn’t care. We were looking at favorable horizons in a zone of promising mineralization. We filled half a dozen canvas sample bags with ore and tagged them with the GPS coordinates of the mine entrance and their locations inside the mine. As far as I was concerned, we had our packs full of cash money.

The hell of prospecting is humping the ore. The fever helps lighten the load, but hauling 30-pound sacks of rock for several miles over rough terrain makes a man irritable. So when Hankla also chose to carry a yellow columbine back to camp for Claire, I was not amused. The fact that he put the flower in an old glass bottle we’d found, filled it with water, and strapped it to his stupid little frameless backpack only exasperated me further.

“You’re not in the story,” I told him as he picked up his pack, the flower bobbing gaily in its vase.

“Good,” he said. “I don’t want to be.”

By the time we made it back to camp, I was in a better mood. We unshouldered our packs and hefted the ore sacks onto the camp table like bags of stolen bullion.

The fiasco with the horses an hour later tempered our enthusiasm a bit, but not for long. By the next morning the emotional dust had settled, and we spent the next two days accumulating more samples.

Conversations at night around the fire generally focused on four topics: gold, how to find gold, Flint’s misadventures looking for gold, and what one should do if one actually finds gold. Nineteen states, most of them in the west, allow upstanding U.S. citizens to claim mineral wealth found on public lands. That land doesn’t include state or national parks or monuments or wilderness areas, but it does include much of the 400-some million acres managed by the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. That means that anyone can stake a 20-acre claim that gives him mineral rights from the surface to the liquid center of the earth, and he can stake as many claims as he likes, provided he pays the initial filing fee of $212 and the $155 annual maintenance for each one.

On the last day in camp, I staked a 20-acre claim over the Lost City. At each corner and at the center of the claim, I piled rocks three feet high over a prescription bottle containing a handwritten note showing the coordinates of the marker and declaring the claim in the names of W. T. Flint Carter and myself. Per Flint’s instructions, I took time-stamped photos of myself holding the note in front of each marker.

Back in town, the party broke up on good terms. We left Flint with some food and painkillers, and he gave us each polished Cody stones with veins that looked like gold and silver. I told him I would get the ore samples assayed, and we all agreed to stay in touch.

A week later, Jason sent me a full geological report and a list of his expenses. Hankla decided to waive his expense reimbursement; the only thing he wanted was Claire’s mailing address. On Jason’s recommendation, I sent an ore sample to a mineral-testing company in Reno, Nevada. I included special instructions for the lab to fully dissociate the pyrite and to analyze the dust in the bottom of the canvas sack. I ordered results for 41 elements, including the most valuable: gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc.

In the meantime, I was still feverish. When the editor of this story didn’t respond after I e-mailed him to tell him that I’d scored big in Arizona, I marched into his office and slammed a chunk of high-grade ore on his desk worth at least as much, I figured, as the iMac in front of him. I planned to stake additional claims around the Lost City and set up an LLC to handle the investments. Jason and Flint agreed to be my partners, and Jason started thinking big.

“No use having only one play,” he wrote me a week after the expedition. “We should consider some other places to work as well. I have a few in mind, both in the U.S. and in northern Mexico.”

A couple weeks later, Jason helped me decipher the assay. Our sample yielded 0.025 parts gold per million parts everything else. That’s 2.5 parts per billion. If you lined up a billion beer cans end-to-end, they’d wrap around the Earth nearly three times. Two and a half of those cans would be pure gold.

“That is complete bullshit,” Flint said over the phone when I broke the assay news to him. “I hope you didn’t spend money on that.”

Jason was more optimistic. Based on the assay, the silver, copper, lead, and zinc in the rock made it worth about $466 per ton. Factoring in a few minor costs, that worked out to a 250-ton haul truck carrying $95,000 worth of ore.

“That is excellent,” Jason wrote. We should “follow up with additional mapping and sampling and an eye for drill targets.”

Before we left our camp in Cañada del Oro, Flint and I had cached more than a dozen sacks of ore that the horses couldn’t handle. Our plan is to revisit the claim this winter to take more samples, stake additional claims, and fetch our cache. Our friends think we’re still afflicted with the fever and say things like “Will, a new mine will never open so close to a ski area,” but funding is the only true obstacle. Jason says he’d be willing to work for his rations. Flint is trying to sell more jewelry and, as soon as he’s able, says he’ll float some cash toward additional expeditions. He also suggested another option: “If the magazine will grubstake us, we can go back. But I’m not sure they’re into that kind of thing.”

Will Grant wrote about the Mongol Derby, the world’s hardest horse race, in May 2013.