In athletics, there’s a long-held belief that greatness demands specialization. To be the best, you have to start young and maintain a laserlike focus. The archetypal example is Tiger Woods, who reportedly started swinging a golf club before he could walk. Recently the focus has shifted to grit. The secret to success, we’re told, isn’t skill but the ability to persevere. Yet that may not be the whole story. In his book , David Epstein challenges arguments for specialization and grit, arguing that a more generalized approach is the surest route to excellence. ���ܳٲ������’s Christopher Keyes spoke with Epstein about the advantages of doing a bit of everything and why the most telling story of a superstar athlete doesn’t come from golf, it comes from tennis.

Podcast Transcript

Editor’s Note: Transcriptions of episodes of the ���ϳԹ��� Podcast are created with a mix of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain some grammatical errors or slight deviations from the audio.

[Advertisement]

---------------

EPISODE BEGINS

���ϳԹ��� Podcast Theme: From ���ϳԹ��� Magazine and PRX, this is the ���ϳԹ��� Interview with Chris Keyes.

Peter Frick-Wright (host): If you've paid any attention to golf in the past 20 years, aside from pointing out how it's basically a giant waste of spaces that could be parks, you've no doubt heard the seemingly mythical but actually fairly true story about Tiger Woods. The story goes that before he could even walk, Tiger was using a putter and, one time as a kid, went on TV and beat the Golf-loving comedian Bob Hope in a putting contest. He was two. Then he won his first competition at eight years old. You probably know the rest.

(clip from Tiger Woods’ first golf tournament)

Announcer: There it is! A win for the ages!

(clip ends)

Frick-Wright: Tiger’s story is often held up as an example of the advantages of specialization. The idea is that if you want to reach the pinnacle of a sport or field of study, you have to start young and maintain near laser-like focus from day one. If you didn't pick up a putter until you were five, well you're too late. Recently, this level of specialization has been associated with another term: grit. This trait, a sort of “stick-to-it-tiveness,” has been praised recently as the actual secret to success. More important than skill or raw talent is just how long you're willing to persevere, whether it's a sport, an instrument, or a field of study. The advice is the same, start early, focus intensely and practice deliberately. Everything else is just distraction.

Yet that may not be the whole story. In his new book, Range, author David Epstein challenges the idea that specialization and grit are the proven factors for success, and instead argues that taking a more generalized approach, while slower in the short term, may be the surest route to excellence. Recently, ���ϳԹ��� editor Chris Keyes spoke with Epstein about the advantages of being a generalist and why the most telling story of a famous athlete’s path to greatness doesn't come from golf. It comes from tennis. Here's Chris.

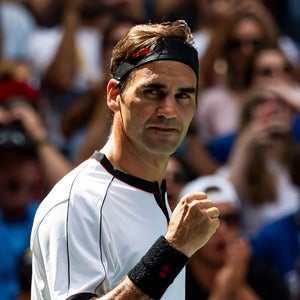

Chris Keyes: What drew you to look at the examples of Roger Federer and Tiger Woods? What are the differences in their path to greatness and what did you learn from that?

David Epstein: Like even if you don't know the details of the Tiger Woods story, people have probably absorbed the gist, because it’s maybe the most famous developmental story of all time. I think it's definitely fair to say that Roger Federer is every bit as famous as an adult, as an athlete as he is.

But people usually don't acknowledge his development story, which is that he dabbled in a number of sports. His mother was a tennis coach, refused to coach him, because he wouldn't return balls normally. When his coaches wanted to bump him up to a higher level of competition with older boys, he declined because he just wanted to talk about pro wrestling with his friends. And he dabbled in like a dozen different sports or handball, basketball, soccer, badminton, swimming, wrestling, skiing, a little bit of rugby. And that turns out to be the norm even though it feels like the exception. And so I thought these two guys who are two of the most famous athletes in the world and really known for at least at a certain point, dominating their sport, would kind of demarcate the polar opposite ends of this debate in an effective way.

Keyes: So if Roger's path is the norm, why have we arrived at this place where Tiger’s model is held up and where specialization -- we put such a premium on specialization and getting our kids into a certain track so early -- why has that prevailed?

Epstein: I think there's two main reasons. One is the story is just incredibly dramatic. It's intuitive that a headstart in whatever it is you're eventually going to do would be the best way to go. As I explored a lot of this research initially I found it deeply counterintuitive and one of the themes of Range is that sometimes the things you can do to cause the fastest short term results undermine long term development. I really found that counter intuitive and so I can understand why other people do. And I think it's a tidy message also, right? It's a lot more confusing to say, well sample some things, and Zig and zag, and find your spot. It's a much tidier message and much more intuitive message to say pick your thing, stick with it, work hard because those are good values. To say like you should work hard at things I think is a good value. It's just maybe our intuition isn’t set up in such a way that we always do what's the best for our long-term developments. I think that's one side of it.

The other side of it is a little more nefarious, which is -- when I was living in Brooklyn up until pretty recently and there was a U-7 travel soccer team that met at a park near me. And I don't think there's a human being in the world who thinks that six year olds can't find good enough competition in a city of 9 million people that they have to travel, you know? But those kids are customers for whoever's running that league. And so they have a really vested interest in keeping them away from other sports and from other leagues.

And so I think in some countries, like Norway, where you see a more holistic development model, you see something different. There’s not as much pressure to specialize early. And, there was just an HBO Real Sports about their sports development. They like exploded the last winter Olympics, maybe the greatest winter Olympic performance ever. And they're not going toward this specialization. In the U.S., where our sport development is much more balkanized, you have a lot of youth coaches whose only incentive is to win like the eight year old championships. And if that's your incentive, then you should specialize those kids and teach them technical skills and how to run plays and all these things that might not be best for their long term development. But if your only incentive is to win the eight-year-old championships, I think it's no surprise, how people behave.

Keyes: Yeah, it's interesting. When I finished the book, I was like, he probably doesn't know this, but this is essentially a massive indictment or, at least a cautionary tale, against modern parenting. Because so many of the choices we make for our kids or the way we push our kids nowadays seem to be in the wrong direction. And I want to talk a little bit about one of those, which is this cult of the ‘head start.’ So obviously the tiger model can work, but what do we know about why it's less effective? Or do we know that in the long run that kids that early specialize aren't as successful?

Epstein: Yeah, so I think there's some domain dependent issue here. So, and that's sort of why early in the book I tried to set up this distinction of the ‘kind versus wicked learning’ environment. And those are terms coined, not by me, by a psychologist named Robin Hogarth. And what he meant by ‘kind learning environment’ was a domain where there are clearly delineated rules. Maybe people even take turns. Next steps are clear, the goals are clear and they don't change from one year to the next, or whatever you're doing will look next year like it did last year. You can count on repetitive patterns and importantly you get feedback that is automatic, usually rapid and a hundred percent accurate. So golf is a great example of that. In those kinds of environments, people tend to get better just by effortful practice alone in whatever the task is.

So some of the people who study golf classify it almost as an industrial task. You're trying to do certain known things over and over with as little deviation as possible basically. And in those areas, I think specialization works quite well where the goal is to be repetitive. In the ‘wicked’ learning environment, the rules may or may not be clear, they may change; you can't count on repetitive patterns. The task might look different next year than it did last year. You may or may not get feedback and it could be delayed or it could be inaccurate. And in those areas, you have to do what psychologists call transfer, which is taking skills or knowledge and apply them to problems that you've never quite seen before. Maybe they're similar or maybe they're totally different, which is called far transfer. So you have to be set up to do things that you haven't exactly done before.

And in those cases, there's this classic research finding that psychologist summarized as breadth of training predicts breadth of transfer, meaning the more you need to be capable of facing new problems that you haven't quite seen before, what predicts your ability to do that is how broad your training was early on and how much you were forced to build these more general skills that you can then apply flexibly when you see something you haven't seen before. And my feeling was that is most of the world that most of us work in to one degree or another. Even most sports require more dynamic challenges than something like golf, which is why I thought it was not good that so many books extrapolate from the Tiger Woods model. It clearly worked for Tiger Woods. I think the problem is extrapolating it to everything else that people do, which is the case for a number of bestselling books.

Keyes: As you point out over and over in the book, this idea that having this broader understanding, whether it's physical skills or mental skills or breadth of knowledge, seems to apply to almost everything that we do these days. And yet there seems to be a real decline in the appreciation of the sort of classic liberal arts education where you go to college and you study a bunch of things. Do you see these kinds of findings having an impact on that where we're going to go back to saying, actually we were right? This idea that we're not preparing our kids by not having them specialize and be ready for the ‘real world’ is actually the opposite -- They need to do as many things and study as many things in college as possible.

Epstein: That's a really interesting question. In the chapter where I write about analogical thinking. It's when you have to face problems that you haven't seen before using drawing -- how powerful it is to draw on analogies of structurally similar problems for other domains, and how that makes people both generate more creative options and much more likely to solve the problem. Toward the end of that chapter, I talk about Deidre Gantner, the Northwestern professor who's probably the world expert in analogical problem solving. She created this test that essentially looks at how good someone is at solving problems that aren't just directly in their own domain. Things that they really have to grapple with new knowledge. She was testing Northwestern students cause she's a professor there, and what she found was that the students who did the best were the ones who had no major but took a broad variety of classes. Some of them were in this thing called the integrated science program where you don't have a major, you just minor in a bunch of different sciences, and the goal is to learn how each of those different disciplines approaches problem solving and what kind of frameworks they use. And those were the kids who did the best. And so that's an interesting thing to know.

Then when I went around and talked to her colleagues, they were saying, we're not big fans of that program because those kids get behind. So here you have like the world's expert in this very important type of problem solving saying, here are the kids we’re doing the best with, and her own colleagues saying, yeah, but those kids are behind. Which just splits my head in two. So I do think that's a real problem, that there's an argument to be made that kids should have a broader education. There's evidence behind it. And yet even other scientists who should, who should be thinking about it scientifically seem to resist it. So it's both from the problem solving perspective --and there was, I don't know if this resonated with what you're thinking about, but an economist who studied the advantages and disadvantages of specialization in timing in higher ed, found that the people who sample and then specialize later do indeed get out behind in terms of income right when they get out of college because the early specializes have more domain specific knowledge. But by year six, they catch and surpass those early specializers while the early specializers end up leaving their career path entirely much more often because basically they were made to choose so early -- that they made a poor choice and the later specializers got a chance to sample just like athletes. And so they made a choice with better match quality, which is the economist term for the degree of fit between one's abilities and interests and the work that they do. And so those people end up with higher growth rates, which in the long run turns out to be much more important than getting out to a head start.

Keyes:There's a sentence that I had written out here because I was so fascinated by it. It applies to this -- you said for a given amount of material learning is most efficient in the long run when it is really inefficient in the short run. So what do you mean by that and how do you apply that inthe real world?

Epstein: Yeah. And it reminds me of the cognitive psychologist, Nate Cornell, who featured in that chapter a lot where I remember he told me, difficulty isn't a sign that you aren't learning, but ease is. So if things are coming too easily, you're actually probably not learning very well. And so what I meant by being inefficient in the short term is there are few techniques for learning that -- there’re very actually small number of techniques for learning that are really well supported in cognitive psychology, even though there are bajillion that have been tested and learning hacks that you can find all over Facebook and LinkedIn and things like that. But the number that are supported are things like spacing and interleaving.

To give you an example, spacing is -- in one of the classic studies, a group of people who knew no Spanish. One group was given eight hours of Spanish vocabulary to study on one day. The other group was given four hours on one day and then a month later they were given another four hours. Everyone had the same instructions, just one group got a much more efficient way where they had to wait a month between the second study session. When they were brought back eight years later with no studying in the interim, the group that had the spaced practice remembered 250% more. And it turns out that the most efficient way to retain knowledge is basically to learn it and then wait until you've just forgotten it and then learn it again. And that's how you basically transfer it to long-term memory, but that feels really inefficient, right? Why not do all your eight hours today?

Keyes: That blew my mind. We still don't even get that.

Epstein: And interleaving, the other one, is -- there was just a study that just came out that I would've loved to include in the book about interleaving, which basically people often know as mixed practice and this translates to physical skills too. People might know variable practice where instead of doing the same exact thing over and over, you're supposed to kind of mix it up. Robert Bjork, one of the eminent researchers in this field, has said that Shaquille O'Neal should have stopped trying to shoot from 15 feet free throws and should've been shooting from 14 and 16 and 17 and 13, cause motor modulation was the problem.

But anyway, this interleaving study that I wish would have been out, that just came out, randomized seventh grade math classrooms to different types of study. Some classrooms got what's called blocked practice, where you get problem type a and then you [do] type AAA BBB, CCC, CCC. And the students make progress really rapidly cause they're trying the same problems over and over. The other classrooms got interleave practice where instead of doing those in a row, you mix them all together and all these different ways. The students have no idea what type of problem is coming after another. And so instead of learning how to execute procedures, they learn how to match a strategy to a type of problem. But it's more frustrating for them, they progress slower initially, they often rate their teachers worse. But when both these groups came along to test time, the group with the mixed practice or the interleave practice destroyed the other group. It was probably the largest effect size I've ever seen in a randomized learning trial. So the effect size was on the order of taking a kid from the 50th percentile and moving them to the 80th percentile just by interleaving their practice, which frustrates them and slows down their progress initially.

It's really some of these so-called desirable difficulties that make the learner feel like they're learning less, slow down their initial progress, but when it comes to having to solve new types of problems, it works like rocket fuel.

Keyes: And does that apply to like learning a new sport as well? And how would you approach that?

Epstein: I think it absolutely does. I mentioned in court as sort of a footnote, there's some areas where learning physical skills and learning more strictly cognitive skills, even though sports skills have a lot of obviously cognitive components, where they diverged but mixed practice -- or interleaving or variable practice, like people use different names depending on what area they're studying it in -- applies to both purely cognitive tasks and to sport learning.

So I would say, to put it in kind of a context that I think is important -- to go back to that, that U7 travel soccer team, right? When I saw these kids playing, they're playing on a full-size adult field. They're learning to run plays and all these things. When you go to Brazil, what you see as the kids are playing futsal, right? And small ball stays on the ground. One day they're playing on sand. The next day they're playing on cobblestones. The next day they're playing on a tennis court over the net. The shape of the playing field is different every day. And sometimes they have different numbers of people, sometimes they’re playing in really small areas, different surfaces. And so I think introducing as much variability as you possibly can is a really good thing to do. And I think to some degree people are familiar with that. Like puritization,over the course of a training segment, you have to change the things you're doing if you want physiological adaptation. And I think that that absolutely holds true for learning new sports skills.

One of the really interesting things, by the way, I spent some time talking to the physiologist for Cirque de Solei and they have a bunch of Olympic athletes and they're performers too. He was telling me that they had started a program where they started having performers learn the basics of like three other performers disciplines, not because they were going to perform them. But wondering if it would make them better at what they do and have other advantages. That's a serious commitment, right? If you're going to take away from people who have to do all these performances, take away from the time they have to do deliberate practice in their main discipline, it must be pretty serious. And what they found was it lowered the injury rate, they track their injury rates compared to Canadian gymnastics, it's a Canadian company, and it lowered their injury rates by like 30%. We can speculate as to why exactly that is. I have theories but I don't know that anybody knows for sure but the empirical finding is that it makes them less fragile and it isn't even about less time in training. It's just about diversity in training. I think there's similar findings for youth athletes like that where it's less total time necessarily that that predisposes them to these like adult-style overuse injuries. And if you diversify, there's some kind of protective effect even if it means you're spending just as much time in sports overall.

(advertisement)

Keyes: You mentioned the word counterintuitive a lot -- this entire book is counterintuitive. Every chapter almost knocks down, something that we all hold true. And one of the big ones these days is this idea of grit. And I know there was a principal at my kid's school who was passing along a book to all the parents about grit and how important it is. What is grit and why is it actually not as good a predictor as we thought it was for a kid's performance in the future?

Epstein: Yeah. So grit -- I know everyone probably knows the colloquial use of the word, but the psychological construct of grit is based on a 12 question survey. Half of the points are awarded for, essentially, resilience and half of the points are awarded for, and I quote, “consistency of interests.” The most famous study, for example, was done at West Point on the U.S. military Academy on incoming cadets, and grit turned out to be a better predictor of who would get through what they call ‘beast barracks,’ which is the six week orientation where you're basically taking high school kids and turning them into officers in training. So it's physically and emotionally rigorous. And grit turned out to be a better predictor of who would get through that than the whole candidate score, which is like standardized test scores and athleticism and all this other stuff. And most people do get through beast barracks. Not many people leave, but that's good to know that it's a good predictor of that.

There are a couple of issues with that. First of all, the study starts like all the studies of grit pretty much -- so some of the others start with people who are already in the finals of the National Spelling Bee. So the study starts by pre-selecting someone for a very short term goal already and, of course, life’s not a six week orientation or the finals of the National Spelling Bee. And so this measurement that penalizes people for changing their interests starts by choosing people at the beginning of a very short term goal. And so it sort of bakes that into the results, the fact that they will do better by not changing their interest in the next six weeks while they have this task to accomplish.

And that's a problem statisticians call it restriction of range. When you select people in that way, and I should say the researchers themselves point this out in their papers, that this is a limitation of their research. That just didn't really survive the translation to the public I would say. The other issue is in the longer term. Grit ceases to be predictive in that way. So if you look at these cadets at West Point, if you zoom out -- they have a five year commitment after they graduate -- those gritty cadets since the early 1990s, about half of them have been quitting the army on the day that they are allowed. And the army initially thought that this was a millennial issue. You know, that like the millennials had a grit problem and West Point developed a grit problem overnight. So much so that a high ranking army officer suggested defunding the U.S. Military Academy cause he said it was, quote, “an institution that taught its cadets to get out of the army.” Which is doubtful, right? And well it turns out, a group of officers and scientists decide to study this problem for the Army Strategic Studies Institute. And what they found was that West Point didn't develop a grit problem overnight. It developed a match quality problem. So the strict upper-out structure of career progression in the army had worked fine when we were an industrial economy where firms were very specialized, people could expect work next year to look like last year. And that also meant that there were huge barriers to lateral mobility because experience in a particular task was so important. But then we switched to the knowledge economy right around when this trend takes hold, and suddenly there's a premium on workers who can engage in knowledge creation and problem solving and skill transfer, the ability to deal with problems they haven't seen before.

And so suddenly these highest potential officers are seeing that they have those skills. They're not giving any agency over career matching in the army, but now there's tons of lateral mobility in our economy. So they start leaving to find better matches. And in fact it played out such that the more likely the army was to identify someone as high potential and give them a scholarship, the more likely they were to quit as soon as they could. And it's not because they weren't gritty, it's because they weren't allowed to search for good match quality. And so at first the army tried to throw money at these officers and the ones who were going to stay took it and the ones we're going to leave left anyway and that was a half billion dollars of taxpayer money down the drain, didn't change retention at all. Then they started programs like one called Talent Based Branching where instead of saying, okay, here's your career path, go up or out, they said, here, we're going to pair you with a coach, try this one career path, reflect on how it fits you with your coach and your interest and abilities. Then try this other one, this other one, these other two and we'll triangulate better match quality for you. And they've had much better luck with retention doing that than they did throwing money at people.

And so I think it really resonated when one of the researchers told me this phrase I love: when you find fit, it looks like grit. Meaning when you get people in a spot that has high match quality for their interest and abilities, they display the characteristics of grit anyway, even if they didn't before and they persist longer and they work harder and their performance is better. And so I think the idea that some people have taken from the grit survey, that changing interests signals that you're destined for low performance, is basically the opposite of a huge body of research that shows you should change interests in an effort to maximize your match quality because you will take on the characteristics of grit once you get a good fit.

Keyes: So how does one with a solid career, pretty happy in what they're doing, but if you anticipate the fact that your personality and desires are going to change over time, how do you, within the structure of a career, do that sampling and, and get that wider range of opportunities to see what's possible?

Epstein: I'll tell you what I do, and I was heavily influenced by the work of Herminia Ibarra. who talks about how people who -- I mentioned her research in the book about how people make successful career transitions and she studies people who make unsuccessful career transitions also. It really resonated with me as someone who was living in a tent in the Arctic as an ecology researcher when I decided to try to become a writer. What I have done is -- when I was a college runner and when I got out of college, I transitioned my sort of training journal, my goal book to the rest of life and actually found out it didn't work as well for me because track and field goals are a lot cleaner than goals in the real world. And I've switched over now to what something Herminia kind of encourages, conceptually what I call my book of small experiments, where at least every other month I have to have a hypothesis where I want to learn something, I want to explore something, some skill I want to develop, and I have to find a way to go about testing it and come back and then reflect on how well that worked. And am I more interested in this than I thought, am I less interested in this than I thought, did it teach me something I didn't expect? Did it teach me nothing at all? And keeping this book, I forced myself to do that every other month.

Keyes: So give me an example of one of those things that you've --

Epstein: One that was really fruitful for me during the writing of this book. I kind of got stuck in the writing at a certain point and in the years leading up to this book I had been working at ProPublica doing investigative stuff and -- I'll tell you the experiment. The experiment was I decided to take an online fiction writing course and what I wanted to do was try a different form of writing than what I was used to. It was one of the first things that popped up, I saw an ad for an online fiction writing course. So I take this beginner's online fiction writing course, nothing I've done matters, nobody cares. And one of the exercises we had to do was writing a story with no dialogue whatsoever. And I found that pretty difficult.

For whatever reason, it kind of knocked me out of my normal mode, where doing investigative work at ProPublica I'd been leaning on quotes a lot, cause you want people to explain things in their words a lot in investigative work if you can. And I realized that in the manuscript of Range, I had been leaning on other people doing explanation that I should be doing. And in many cases, I was leaning on that because I didn't understand what I was writing well enough to feel confident that I could write it instead of just allowing it to be in their words. It sort of made me cognizant of that. And I went back through the whole manuscript, dove deeper on some of the things that I sort of was finessing that I didn't quite understand as well. Took out a huge number of quotes and, I guess I don't know, the counterfactual because the readers don't get to see the other version. But I think it made it a much better book. And it also attuned me to the fact that I was, without thinking, sort of leaning on a certain kind of writing and that had just become automatic and very comfortable for me. I found that to be a very fruitful experiment, not all of the experiments I enter are that fruitful, but that one caused me to then take another one and has really improved my writing. And so I'm gonna keep looking to engage in forms of writing that aren't the kind that I just come into direct contact with from my work.

Keyes: I really was fascinated by the idea of this, experience does not lead to expert judgment. What do we know about that and why is that not the case?

Epstein: And this gets to someone who I think is maybe the most underappreciated scientist of the 20th century, a guy named Paul Miele, who first did this in 1954. He wrote this book where he just looked at all of the research he could find about expert judgment. Essentially, it could be psychologists predicting how patients would respond to treatment. It could be college admissions officers predicting how people will do in school, social workers predicting recidivism, HR people predicting how well someone will do in job training, all these things. And what he found basically was that with experience, these experts became more confident but not more accurate, even when shown how inaccurate they were. I think that launched a whole field of study about cognitive bias. So without Paul Miele, there's no Daniel Kahneman who won the Nobel prize for eliminating cognitive bias. He was sort of inspired by Miele’s findings.

When we're not in those ‘kind’ learning environments -- basically we seem to intuitively treat the whole world as if it's a ‘kind’ learning environment like golf where you do something and because you experienced it and you perceive some result, you think you're getting better. But in fact most domains that's not the case. We're not that good at intuiting cause and effect. The feedback is usually delayed. So we have to find ways of learning other than direct experience. And if we're unwilling to do that, it leads to some pretty bad results. Chapter 10 is focused on expert predictions of trends in the world. And we’re all constantly making predictions in our lives, whether it's about what we should be doing for work or who we're going to marry.

We're constantly making usually implicit predictions. And what that work found was that the more narrow experts were, so the more -- if they had spent their entire career on one or two problems, typically the worse they were at making predictions about the world. They knew so much about a very narrow area that they would fit any situation to their sort of narrow lens and they could do that because they had so much information in one narrow area that they could always find something to cherry pick. And in fact, those people got worse as they accumulated experience and credentials. They were so narrow, they get worse, because as they get more and more lauded in one particular very narrow area, they increasingly see the entire world through that mental model. Whereas the people who did really well in forecasting, often members of the general public, who in forecasting tournaments outperformed CIA analysts with classified, with access to classified data, those people were very broad and they didn't stick to a particular mental model. They went around and gathered up different perspectives on all these issues they were trying to predict.

As Philip Tetlock who did this work said they have dragon fly eyes -- dragonflies eyes composed of thousands of lenses. Each one takes a distinct picture and they're integrated in the dragonflies brain. And so they weren't sort of anchored in any one area of experience. And that allowed them to be a lot more flexible with whatever problems they approached in the world. And they ended up having really, really good judgment.

The problem is there was an inverse correlation between how good people were at making forecasts and how prominent they are. So like the people who are on the news making predictions were the least accurate, but they are the most prominent, and their narrow view of the world allows them to speak really authoritatively, which is why they make for good television, but they don't actually make good predictions. So we really kind of have this backward.

Keyes: So this, that was the part that really resonated for me in a bad way cause I just, it made me reconsider my whole belief in whether I know what a good story is or not. Cause we have these story idea meetings, once a month. And my sense is that, well I've been the editor here for 12 years. I have a pretty good radar and can see a story and say, ah, that's gonna work, but now maybe I should just get a group off the street to come to this meeting and tell us if this story is going to be a success or not.

Epstein: Well, those volunteers, they were people who were proactively, they had a lot of the whole active open-mindedness. So they weren't just random volunteers. They were people who really have these wide ranging reading interests. And my guess is you read a lot. Reading a lot and reading widely was like one of the main attributes of those people. That's probably something that you do. So you probably have a lot of cause for having good judgment in that area. People can get better at this and so Tetlock tested some training regimen to see if people could get better at making these kinds of predictions. And he found they could. And probably the two most important parts of the training, in terms of the effect they had on people, were one, just keeping track of your own judgments and which ones went well and which ones didn't. Apparently just keeping track makes us a lot more cognizant of when we go wrong and otherwise we kind of only remember when we went right mostly and like a few instances of when we went wrong.

So keeping track had a huge effect and so did what was called ‘reference class forecasting,’ which basically means, instead of thinking about all the internal details of this story or this project or this investment -- our natural inclination is to focus in on the internal details, every detail we can get about the case at hand, and it's called the inside view. But the best thing to do is actually to start by saying, what other cases that have structural similarities to this can I think of. I'll gather as many of those as I can and think about how those went before I moved to the internal details. So switching the order of how you do that. So when people start with the internal details, they just stick with them. But if they start with that outside view of looking for other structurally similar say stories, in this case, that's the place to start before you move to the internal details and it had a big effect on how good people's predictions were when they started with that outside view of looking for structural similarities as opposed to focused on the internal details.

Keyes: I want to end where you end at the end of the book, which kind of made me chuckle. Because every time somebody does write a book like such as this, the immediate thing that people want to know, including myself is like, okay, David, so you found all this out, give me a sentence about how to apply this to my life. And so you went about trying to figure out that sentence and it was actually one of the big takeaways that I found so encouraging about this book that’s kind of buried in here, which is this idea of like, don't feel like you're behind. Which is what we're kind of made to feel all through our life. And even if you're in your mid-forties and looking to do a career change, what might stop you from doing that is like, well, I gotta start at the beginning and I'm way behind all these other people who have started a career in this. But why was that your main takeaway from all?

Epstein: I think on the one hand it was, again, getting to that theme of, if you're willing to adopt the principles of optimal development, they aren't always what causes the best short-term progress. Also the fact that interaction -- I explained this in the introduction -- some of my interaction with military veterans who were given scholarships by the Pat Tillman Foundation to aid career changes when I first interacted with them, these are former Navy seals and Delta force and all this stuff, how behind they felt struck me because to me, these people just exude excellence, coming out of their ears everywhere they go. And they felt so behind. And I had felt that too when I left training to be a scientist and I arrived at Sports Illustrated, there were a couple odd jobs between there, but as a temp fact checker, six years older than the people I was doing the temp fact checking for.

I really felt profoundly behind. But then it turned out that taking my very ordinary science skills and bringing them over to a sports magazine, they were suddenly seen as extraordinary. So I shot from temp fact-checker to the youngest senior writer, like very quickly. But I remember that feeling of behind and I've been that way when I then transitioned to ProPublica. But those transitions have been great. I realized that it's much more productive to compare yourself to yourself yesterday than to look around and see people who are younger than you and have more than you because we aren't on -- I think we perceive people as being on linear trajectories, but we most certainly are not. And so I think considering ourselves behind, we don't really, our assessments aren't really accurate and it doesn't do anything productive for us. So I think the start of being willing to adopt any of the findings of any of the signs in the entire book, almost the prerequisite is not feeling so far behind that you're unwilling to try those things.

Keyes: Well David, thank you so much for talking with us.

Epstein: Yeah, I appreciate it. I'm a fan and longtime reader, so it's, you know, it's cool for me to be able to do this. I appreciate your interest.

---------

OUTRO

Frick-Wright: That’s Chris Keyes. I'm talking with author David Epstein. His book is Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. This episode was produced by Robbie Carver, and Mike Roberts. It’s brought to you by Bob's red mill, making the ingredients for proper nutrition for athletes more at Bobsredmill.com. The ���ϳԹ��� podcast is a production of ���ϳԹ��� Magazine and PRX. We'll be back next week.

Follow the ���ϳԹ��� Podcast

���ϳԹ���’s longstanding literary storytelling tradition comes to life in audio with features that will both entertain and inform listeners. We launched in March 2016 with our first series, Science of Survival, and have since expanded our show to offer a range of story formats, including reports from our correspondents in the field and interviews with the biggest figures in sports, adventure, and the outdoors.