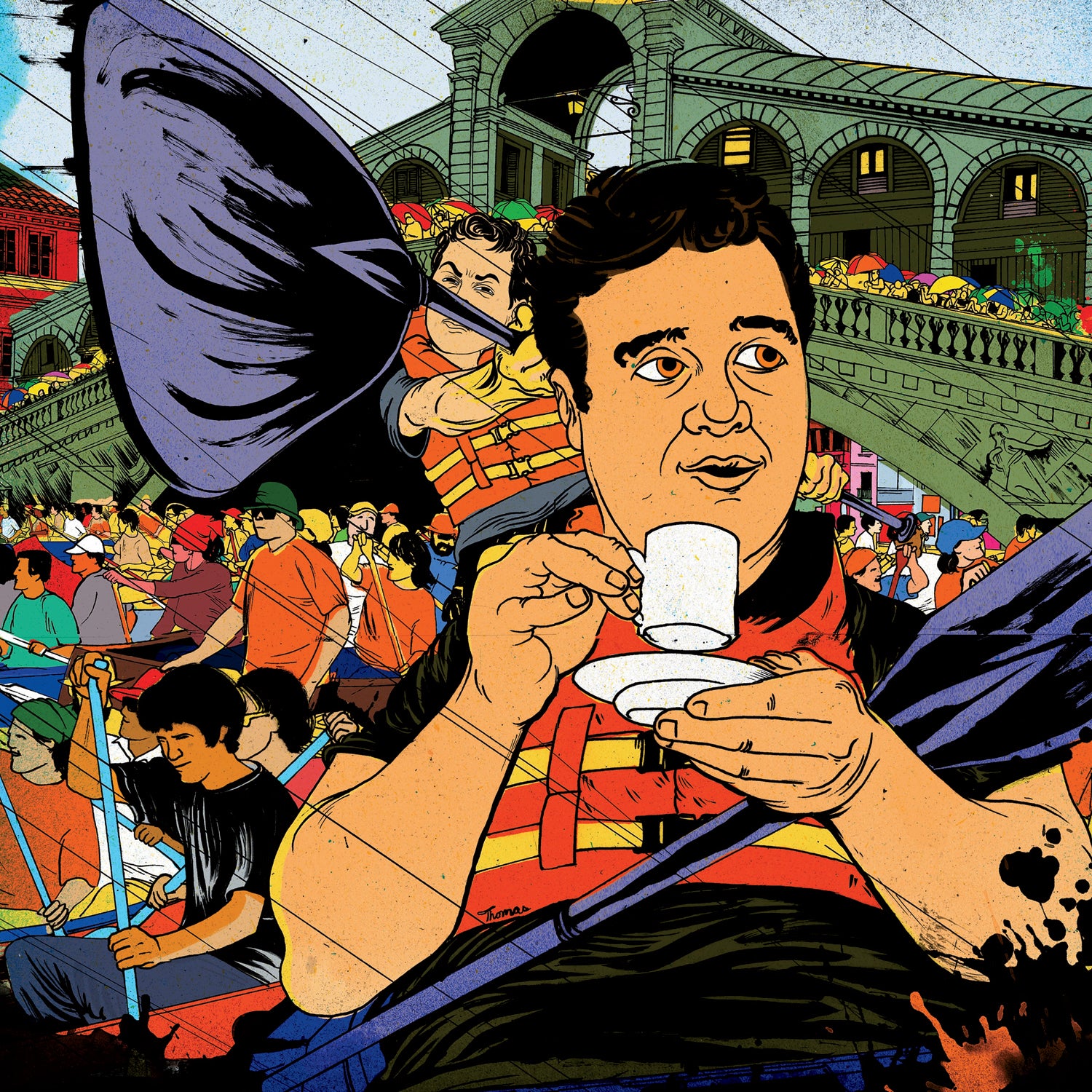

MY BROTHER DAN AND I ARE 40,000 FEET over the Atlantic, bound for Venice, where we will spend five days doing nothing much beyond paddling a kayak through some of the comeliest urban waterways on Planet Earth. A national media organ is picking up the travel costs. Yet, somehow, we are unhappy.

Venice

Guido Baviera/Corbis

Guido Baviera/CorbisVenice

“I'm getting the feeling that this whole thing is gonna be an insane bitch,” Dan says, glowering at the guidebook splayed on his lap. He's been reading up on our trip's capstone event, the Vogalonga, a 19-mile noncompetitive rowing regatta, held in late May, that promises a breathtaking tour of the old republic's lagoon and outer islands. “Man, you didn't tell me 'Vogalonga' means 'long row,' ” he says. “And check this out.” He flips to the guidebook's back cover, where the author has listed among his credentials “one attempted Vogalonga.”

“Attempted,” he repeats, anxiously pinching an ingrown hair on his cheek. “I'm a little worried we won't get this fucker done.”

I'm worried, too, though not about the Vogalonga. What troubles me is the prospect of spending a week in a tandem kayak with Dan, whom I recently described in print as “the only person in the world I've sincerely tried to murder.” Dan and I do not get along. Our last trip together (chronicled in the April 2008 issue of this magazine) nearly ended in a fistfight. More or less since infancy, our relationship has been a reliable source of juicy conflict, which I've exploited for a shameful volume of column inches. In recent years, I've made so many journalistic and literary meals out of our hostilities that when people ask me what I do for a living, I could pretty honestly say, “I don't get along with my brother.”

Lately, we've both gotten tired of it. “Hey, do you think you could, sort of, not write about us anymore?” Dan asked after the publication of my most recent dispatch on the subject. “It's depressing.”

“I totally agree,” I said. “No more. Promise.”

About four minutes later, my inbox chimed with an e-mail from my editor, who proposed that Dan and I head to Venice for a little float.

“What's next, a reality-TV show?” Dan said when I pitched it to him.

“So you don't want to go?”

“Free trip to Venice? Hell, yeah, I'll go,” he said. “Only problem is we're getting along pretty good right now. I guess I'll have to beat your ass or something so you'll have some material.”

AS IT TURNS OUT, Dan's offer to stage strife is unnecessary. The following morning, in Venice's soign├ę Marco Polo Airport, our contretemps begin in earnest.

I've brought along a brand-new, deluxe, rudder-and-spray-skirt-equipped, collapsible two-man kayak called the Greenland II, a loaner wrangled from Folbot, of Charleston, South Carolina. My enthusiasm for this product is total and tedious and sort of creepy. I have panted about the boat to everyone in my acquaintance. I have brought its spec sheet to dinner parties. For weeks, I've been unpacking the craft to pet its rudder and heft its featherweight ribs while making covetous, Gollumish gurglings in the back of my throat. It's 17 feet long and a scant 62 pounds yet is reportedly untippably stable, with a 600-pound payload, and fits, paddles and all, into a pair of extremely stylish, rubberized canvas bags, checked through to Venice for no additional fees. Yet Dan, as we wait for the conveyor to disgorge our craft, starts to quibble.

“I don't know about this boat you got us,” he says.

“What are you talking about?” I say. “It's an astounding boat. State-of-the-art. People paddle the Arctic in these things.”

“We should've just rented a canoe. Did you try to rent a canoe?”

“Why the hell would we want a canoe when we have a folding kayak? And, anyway, what are you complaining about? We have a boat, a fantastic boat, and you got a free trip to Venice.”

“What I'm complaining about,” my brother says, “is that we've gotta paddle 20 miles in this thing and it's in a goddamned suitcase.”

In sullen silence, we board a water bus and go bumping off across the lagoon. We debark at the touristic cattleyard that is the district of San Marco, bashing the hefty Folbot duffels into rose merchants and necking couples as we go. Storms of upset pigeons and madrigals of bystander invective herald our approach as we cross the piazza.

With the exception of sun-cured gondoliers grifting for fares, I do not spot another unescorted man. The bougainvillea is erumpent, and the ros├ę-and-apricot vistas of faded plaster look decoupaged from a Barbara Cartland novel. Accordionists traipse after honeymooners, wheezing out strains of “B├ęsame Mucho.” My brother pauses in his tracks to belch, squeeze his ingrown hair, and remark that he would trade any number of accordionists and Murano-glass gewgaws for a good old-fashioned supermarket selling beer and sacked ice.

When Dan and I at last reach our hotel, just before noon, I'm sorry to learn there's been a misunderstanding about the nature of our relationship. Our room, the clerk tells me, contains one double bed. An attempt to leverage my credentials for a room with two beds goes nowhere.

“You will like the room you have,” says the clerk, flashing a licentious smile. “Write that Venice is the city of lovers.”

ONCE SETTLED in our room, I'm suddenly anxious to get our ducks in a row. We have four days until the Vogalonga, and to avoid being left pondering instructions as the regatta heads out Sunday morning, I propose that we haul the Greenland II out to an alleyway, assemble it, and take it for a spin.

Dan, who's lying in our bed and draining a huge can of Peroni, says, “Let's just put it together here.”

“Where?”

“Right here. In the room.”

I look around. I point out that the room is perhaps ten feet long, seven feet shorter than the boat.

“We'll do it on an angle,” Dan says.

“And get it downstairs how?” I ask. We're on the fourth floor.

“Easy,” he says. “We'll lower it down on a rope.”

I point out the tort liabilities of dangling a 62-pound boat 50 feet over a crowded Venetian alleyway; the impossibility of assembling a 17-foot boat in a ten-foot room, diagonally or no; and the fact that we have no rope. None of this sways him. Dan is an attorney and a passionate contrarian, and his zeal for an argument always swells in proportion to its absurdity. He's also a real-estate investor who oversees a fair number of home renovations, and today he seems to feel this is tantamount to an engineering degree.

“Look, goddammit,” he says, “I build stuff for a living. I know what I'm talking about. Go get us a rope.”

“This is insane,” I say. “We're taking the boat to the street.”

Dan sets his jaw. “Man, this is why I get frustrated with you. You're such a goddamned 'my way or the highway' type of dude.”

“What are you talking about? I mean, yeah, in this case, it's my way or your way, which is so colossally fucked up that it's not even a way!”

He cracks another tallboy and settles back against his pillow. “Tell you what, give you an option,” he says in a voice of compromise. “Option one is we put the boat together here and do the thing with the rope. Alternatively, you could take it down to the street and assemble it yourself.”

Here I feel the onset of certain central-nervous-system responses I experience only in the presence of my older brother. My vision goes red. An uncomfortable balloon of rage inflates behind my ribs. I begin to experience a sensation that I imagine is akin to what a werewolf goes through on nights of full moon.

“Are you fucking kidding me?” I more or less scream. “I bring you to Venice and you won't help me put the boat together? Really? Please tell me that again, in a complete sentence, on the record, so that I can write it down.”

He rolls his eyes and lets out a long, forbearing sigh. Then he stands, grabs the nearest boat bag, and leads me out the door.

CURSING AND GRUNTING under the weight of our bags, we plow through the extremely narrow streets of Venice. I've maneuvered Dan into carrying the longer of the two bags, with which he's terrorizing gelato-besmeared tourists as he passes, but this gives me little pleasure.

Ten blocks later, groaning and clammy with sweat, we unpack the boat in a dead-end alley giving onto a placid, narrow waterway a safe distance from the havoc of the Grand Canal, Venice's largest aquatic boulevard. Most of the Ikea bookshelves I've tangled with have been tougher to put together than the Greenland II. Within 30 minutes, it's assembled, an aluminum skeleton sheathed in a comely blue-and-black hide of rubberized nylon. At the sight of it, not to mention the prospect of actually paddling the thing, I'm literally trembling and panting with cupidity.

Yet I am nervous, too. The last time Dan and I were in a small watercraft together, 20 years ago, it ended in first-degree burns (hot brownie batter flung like napalm, long story) and a broken arm (my right ulna, fractured against a paddle Dan was using to block blows to his face). Dan, who outweighs me by 50 pounds, takes the stern, and I snug myself into the bow. The cruise starts off pretty magnificently. We glide through confidential alleys where the sunlight turns the water a startlingly lovely radioactive green; slip under moss-flocked bridges where pale crabs cling; dart between gondolas, our craft swift and nimble as a trout. Dan, at last, seems properly delighted. From the stern, I hear him giggling and cussing with joy. Our paddles dip and draw in easy rhythm, and we are, to my amazement, working in harmony.

I'm a little less worried about drowning on Sunday.

╠ř

╠ř

IF YOU ASK the Vogalonga's organizers about its genesis, they'll tell you that the regatta's origins were lighthearted but that the event soon became political. According to local caterer Antonio Rosa Salva, whose grandfather and father are generally credited with bringing off the first outing, in 1975, the Vogalonga morphed into a protest against the growing scourge of motorboats, whose wakes assail the foundations of Venice's antique buildings, some of which date to the seventh century.

╠ř

╠ř

As we hit the Grand Canal, we meet the motorboats, which likewise begin to erode the morale of Team Tower. Ninety-foot vaporetti nearly swamp us, their smirking passengers taking photographs of us. We churn our way through a Class IV onslaught of propeller wakes as sleek wooden speedboats race past. I am frankly terrified, but Dan utters no words of assurance or encouragement. Rather, he decides that the best response to the rough seas is to ship his paddle and speak exclusively in the imperative mood.

“Paddle right! Paddle left! Left, motherfucker! C'mon, get it in gear!”

“Don't fucking tell me which side to paddle on!” I yell, glaring back. “You're the rudder man. You're supposed to steer! And why the hell aren't you paddling?”

“Because I like how fast we're going with just you paddling.”

We survive the GC and then make our way back through the 1,300-foot-wide body of water known as the Bacino di San Marco, past Venice's thousand-year-old Byzantine cathedral, the Basilica di San Marco, and up into the Giudecca Canal. At last we locate the boathouse where I've made arrangements to garage our craft and soon find a section of seawall with marble steps that might do for a take-out spot. The Giudecca, however, is half a mile across, deep enough to accommodate cruise liners, and the four-foot swells make for a nervous debarkation.

Dan scrambles onto terra firma. I stay in the boat, which is being drubbed against the seawall. “What the hell are you waiting for?” my brother yells. “Get out.”

I don't feel like getting out. Idiotically, we've attached no bowline to the kayak, and I'm afraid that, as I hoist myself ashore, the precious Folbot will float off on the violent tide or I'll get tangled in the spray skirt or I'll simply slide off the slick, mossy steps and into the green Giudecca, whose waters still allegedly contain worrisome concentrations of human and industrial waste.

As I parse my options, Dan squats on the bank, abusing me. “What the hell's the matter with you?” he roars. “Be a man and get outta the fucking boat!”

Red waters flood my vision. “I'll kick your ass!” I scream, though the odds of my kicking anyone's ass in the present circumstances are extremely long. At this point, a laborer laying flagstone nearby takes pity on me, reaches out his hand, and pulls me ashore.

I thank him, and because of his kindness, my blood pressure begins to return to normal. But then the fellow turns to Dan and, nodding at me, says, “This guy, he is not so┬Ś” and points at his biceps.

Dan breaks into braying laughter┬Śand pretty much doesn't stop until he's asleep.

THE FOLLOWING MORNING, Dan and I venture over to the Vogalonga's temporary headquarters, a cavernous marble palace off the Grand Canal where I make the acquaintance of Erla Zwingle. Erla Zwingle is the nicest person I have so far met in Venice, and her musical name, if chanted three times, is sure to buoy your mood. A transplant from Washington, D.C., she's a volunteer for the regatta and a former editor at National Geographic. The Vogalonga press office has been singularly unresponsive to my pleas for tips on good people to interview, so I ask Erla, a fellow member of the fourth estate, for suggestions.

“I know someone you might talk to. He's a native Venetian and has rowed in every Vogalonga since it started,” she says. She pulls out a cell phone and speaks, in flawless Italian, to someone on the other end. “He'd be happy to talk with you. His name is Lino. Full disclosure: He's my sweetie. Are you free for dinner tonight?”

Shortly after eight o'clock, Dan and I join Lino Farnea and Erla at their apartment, which is fragrant with the rich pasta carbonara Lino is cooking while we talk. Erla met Lino, a handsome man with olive skin and a tidy crop of white hair, while on assignment in Venice in 1994. A lifelong teacher of Venetian-style rowing and lagoon lore, Lino was Erla's instructor in the locally cherished set of strokes with which gondoliers manage to propel their crafts with precision and deliberateness while rowing from a single side. The stroke is a rococo cousin of the J-stroke, somewhere between stirring a cauldron and frosting a cake. In the time it took Lino to teach Erla to row in the Venetian way, they fell in love, and Erla decided she had no interest in going back to the United States.

In the course of our conversation, I recount the motorboat unpleasantness in the Grand Canal and ask about the Vogalonga's history of struggle. Actually, reports of the Vogalonga's activist origins are somewhat overstated, say Erla and Lino, who emerges from the kitchen to fill our glasses with wine.

“Yes, the waves caused by the motorboats are the cancer of Venice,” says Erla. “Every time a wave hits the foundation of a building, it carries something with it. On any canal in the city at low tide, you see foundations of palaces with holes in them like this”┬Śshe raises her arms, describing a cavity of beach-ball girth┬Ś”and you wonder how they're still standing.”

“But the Vogalonga didn't start as a pro┬ştest,” says Lino, with Erla translating. “It was born from a bunch of friends who loved rowing, and anyone who wanted could come along. And it's not a protest now. You see the people in the boats┬Śthey're laughing, they're partying. They're not worrying about the problems of Venice. And when the boats have returned to the Bacino di San Marco you'll find the waves of motorboats are back again, so it's absurd to say it's against the motorboats because, four hours later, they're back again. So what kind of protest have I made?”

But while the Vogalonga's PR assault on the gas-powered menace hasn't been entirely successful, early on it revived Venetian rowing traditions, bringing new business to gondola builders. Rowing clubs multiplied. Erla says there are 40 or so now, but membership is anemic and graying. Most kids prefer motors.

Despite the native disinterest, however, Erla tells me that this year more than 5,000 people are likely to turn up for the Vogalonga, the majority of them foreigners in English-style rowing sculls or kayaks or canoes. She and Lino will be part of an eight-person Venetian boat, which, she says, makes for a much less exhausting experience than paddling a solo or tandem craft.

“So,” says my brother, “is this thing like a marathon?”

Lino, uncapping a jug of piquant, gentle grappa and pouring generously, assures us that we'll finish the loop in four hours or so in a kayak. “But,” he says, “it is tiring, and at times it seems impossible. Maybe you think, I'm dead tired; I will never do this again. But when you come down Grand Canal, you get this lump in your throat. You see all the boats, all the people, and what a beautiful thing it is.”

THE NEXT DAY is clear and breezy. Briny mistrals roll in off the lagoon, and Dan and I, in good spirits, fetch the kayak for an hour's jaunt through the canals.

I perch in the bow with the intent of jotting some descriptions down. The trouble with writing about Venice, of course, is that there isn't a single flagstone in the city that hasn't already been fawningly described by scores of hacks. Echoing in my head is Mary McCarthy's line from 1956's Venice Observed: “Nothing can be said here (including this statement) that has not been said before.”

I am nevertheless trying very hard to jot down a few lines about the glories of seeing Venice by kayak, away from the gelato hordes and postcard racks, how on Venice's streets you more or less drift like a ghost through a bethronged nonplace, a place that's not so much a city but a┬Ślet's see┬Śan extremely high-class burlesque dancer so gorgeous and charming that you don't mind that she's not actually a person but a very comely device whose sole purpose is to pry cash out of you, but here in these confidential canals, coasting past barnacle-studded walls and expanses of failing plaster and getting up-close views of the tidal gingivitis line, where the waters are slowly gnawing away foundations of centuries-old brick and marble, it's as though the show is over and you've followed the dancer home, where she's dropped her false grin and scrubbed off her makeup and revealed to you her affecting vulnerabilities, which make you see her as an actual person and not merely a charming photo object and dollar receptacle, etc., etc., yet there's no way to jot any of this stuff in your handy Rite in the Rain waterproof notebook, because your brother is screaming at you to paddle on this side or that side every 15 seconds and you're screaming back at him to, for the love of God, shut up before you jam this paddle as hard as you can against the bridge of his nose, ideally driving bone fl├ęchettes deep into his frontal lobe.

At every canal junction, Dan and I argue about which way to turn. When I pause to put on sunscreen, we argue about that. Snapping a photograph? Of that stupid wall? That's an argument. Putting a camera in the drybag? Argument. It's sort of like having a joint superpower. We're a two-man twist on King Midas, turning everything before us into conflict.

The trouble with arguing about absolutely everything is that you essentially argue about nothing. That is, when an issue such as who got the larger pizza slice inspires the same degree of rancor as, say, whether or not to paddle in front of a speeding garbage barge, it quickly becomes impossible to distinguish an important battle from an utterly idiotic one.

Returning to the storage hangar, Dan and I have our 10,000th argument of the day, this time about how best to land the boat. We've agreed to take out at a floating dock convenient to the boat hangar. I'm for landing at the calm, leeward side of the dock, where there's a tiny bit of seaweed and befoamed trash floating around. Dan makes the case that only a fool wouldn't land on the windward side, where there's a handy, well-worn little step to climb onto, never mind that it's under heavy assault by man-size rollers piling in from across the Giudecca.

I really ought to continue arguing for a leeward landing, but my brother has already used the word “pussy” about three dozen times in reference to the other day's assisted debarkation, and so I say nothing. Wave after wave crashes over the deck as we pull alongside. The boat is rolling. We fight for balance and scream at one another. And then all is cold and quiet and green. We have tipped the untippable.

I come up gasping inside the capsized cockpit, trying not to imagine the solvents and carcinogens I'm soaking in. Dan is elsewhere, treading lagoon water and bellowing my name.

In grim silence, and with considerable effort, we climb the little step, wrest the boat from the water, and lug it up to the sidewalk, where we sit, dispirited and dripping, for a long while. Then a fleet of kayakers arrives at the dock. Without a second thought, all of them paddle to the leeward side and clamber out, safe and sound. As it would be pointless to point this out, I just shake my head.

“I lost my sunglasses,” I say glumly.

Dan has retained his┬Śa triumph, he explains, of his superior coolheadedness in a crisis. “When that boat went over, my first thought was, Where are my sunglasses?” he says. “My second thought was, Where's Wells?”

Many hours later, over dinner, we're still lamenting the spill and assaying blame. Tomorrow is the day we're supposed to paddle 19 miles together. The prospect now seems not only difficult but possibly suicidal.

“Look, man, here's the problem,” Dan says at last. “A ship can't run with two goddamned captains, and two captains is what we got.” He knocks back a dark dose of wine. “Really, I've about had it, man. Why don't you just be the captain? Tomorrow, you sit in back. You call the shots.”

“Fine.”

He shakes his head. “I just didn't expect that we'd be fighting like this.”

“I know. It's like we get in that boat and turn into a couple of five-year-olds. We need to figure out some way to nip these retarded squabbles in the bud. Maybe we need a safe word or something.”

“A what?”

“You know, like a word or something we say to stop fighting, to take a time-out and check ourselves,” I say. “What's a good safe word, do you think?”

Dan refills his glass and mulls the notion with a frown. “How about 'Quit being such a fucking asshole'?”

I SUFFER TERRIBLE VISIONS that night: Our tragic inability to cooperate reaches its fullest expression as Dan and I drown out in the lagoon. Thus far, we haven't been able to paddle 50 feet without vows of fratricide; 19 miles seems an impossible challenge. I can't sleep. Dan, however, is sprawled across 75 percent of our mattress, his snoring like a symphony of madmen blowing into broken kazoos. I fold my pillow over my head and pray for dawn, fretfully pondering tomorrow's route.

The flotilla moves out at 9 A.M. from the Bacino di San Marco. We'll head northwest for a kilometer or two, tracing the shores of Vignole, St. Erasmo, and San Francesco del Deserto islands. Ten or so miles in, we'll hit Burano and then Mazzorbo, after which, according to Lino and Erla, the thrill of the trip begins to degrade. Between Mazzorbo and Murano lies a long, grindingly dull stretch of open water where I imagine Dan and I will pass the time by screaming at one another. From Murano, we'll plod to the homestretch, the Cannaregio Canal, which is usually thronged with exhausted racers vying for position and which, according to Erla, resembles “a little bit of hell.” If we survive the maelstrom at the Cannaregio's mouth, it's on to the Grand Canal, under the Accademia and Rialto bridges, to fetch up at last where we started.

Neither Dan nor I have done a push-up in years, and I've got no experience at the Folbot's helm. If we finish at all, I'll be grateful.

Just before eight o'clock, we set off for the boathouse. I'm agitated and overcaffeinated. Dan, despite his solid eight hours of sleep, is darkly sullen. The air is damp and cool as the wind herds tin cans and pizza tissues over the empty sidewalks. We retrieve the boat and put in on a quiet canal. As Dan eases his 240-pound bulk into the bow, the frame creaks and buckles. With the bow ballasted by my brother's substantial poundage, the Greenland II feels a little less lithe and hydro┬şdynamic than on prior cruises, but we still go slipping gracefully along and enter the Bacino di San Marco seconds before the starting cannon goes off, lofting a tidy white curd of smoke over the holy bulbs of the Basilica di San Marco.

Choking the basin is a riotous mess of boats┬Śseveral thousand of them, spanning every species of nonmotorized craft┬Śjostling toward the lagoon. Gondolas of every description bob along┬Śblack-lacquered, brocaded numbers that look like caskets for heads of state; five-person, vaguely Vikingish barges of unpainted planking. There's a preponderance of insectile rowing sculls, their leggy oars making a nuisance. A team of roistering Germans paddles past in what appear to be two aluminum canoes welded together into one superlong boat. They give full-throated song and, despite the early hour, seem to have already achieved a healthy buzz. Abreast of us, a prepubescent pilots a magenta kayak that looks like a candy cigar. Flags of uncountable nationalities ripple from passing sterns. The horizon is thorny with paddles and oars.

“Jesus, isn't this unbelievable?” I call.

“Ask me in four hours,” says Dan, dipping his paddle.

The array of boats, which range from ancient elegance to jackleg improvisations, makes me feel a good deal better about our odds, perched as we are in our comparatively state-of-the-art vessel. And in the early moments of the regatta, we do a fair job of staying with the fleet. But ten minutes later, rounding the island of Sant'Elena, we're smacked in the face by a fearsome headwind, which helps topple a few boats. (Before the day is over, the rough weather will have upset 30-odd boats and left some 50 people in the drink, awaiting rescue.) The regatta slows to some very glum fraction of a mile per hour.

During the moment of respite between strokes, the Greenland II slides perceptibly sternward. Crafts less sleek than ours are having an even more miserable time of it. To our left, a coed pair of Venetian-style rowers churn against the tide, the woman's white sundress billowing about her in the blue of the morning. By my watch, it takes them seven minutes to move their boat about 15 feet. Windblown sheets of water break across the Folbot's deck, sluicing over the spray skirt and down my shirt to pool electrifyingly in my crotch.

Dan seems to have already abandoned the mission. His body has gone fairly limp, and he's adopted a style that basically involves letting his paddle drag through the water like a dead limb. In as diplomatic a tone as I can muster, I plead with him to deepen his strokes and even out his cadence. He's too tired to give me even a halfhearted “Go fuck yourself.” All he can manage is “This is horrible. Shoulda brought my trolling motor.”

As we near a stretch of coastal scrubland at San Francesco del Deserto, the wind relents. I'm hoping we'll be able to make up some time. “OK, bro, put your back into it,” I call out.

“Pull over,” says Dan, indicating a marshy berm where a crew of Scandinavian oars┬şwomen, having beached their scull, are enjoying a snack. “I'm hungry and I've got to take a leak.”

I protest, “Look, I'm captain, and I say we┬Ś”

“Personally, I'd be happy to piss in the boat. Don't know how psyched you'd be about that, though.”

I rudder us in, thinking that at least I can maybe swap some pleasantries with the ladies while my brother is off in the bushes. But, against my entreaties, Dan unholsters himself right there on the beach and enacts a candid, languorous urination in plain view of the Scandinavians. They move along, and Dan and I picnic in silence on chocolate and wet bread.

By the time we fold ourselves back into the boat, the flotilla has considerably thinned. Lactic acid congealing in our arms, we crawl along the coastline for Burano. Presently, a pair of elderly women paddling arrhythmically in a tandem kayak lurch past us┬Śa painful testament to my inadequacy as captain. I try to pull it together.

“Come on, man,” I call out. “We can't let those old ladies dust us.” Dan grunts in agreement and we strain after them, but it does no good; they soon vanish into the distance, along with pretty much everyone else.

Dan peers over his shoulder. “I don't see a whole lot of people behind us,” he says. I turn around for a look. Save for some guy in a buckskin-trimmed canoe that seems less a viable boat than a gimcrack plucked from the walls of a family restaurant, the lagoon is empty.

DESPERATE TO AT LEAST appear to be a part of the regatta, we bend to our paddles in silent determination. But at the four-hour mark, at which Lino assured us we'd be done, we've just reached the island of Burano┬Śroughly halfway through the course. I'm officially exhausted. With each stroke, an ember of pain glows in my right triceps. As captain of Team Tower, I'm loath to show any weakness in front of my brother, but I can't help letting out a little high-pitched shriek every third stroke or so. Luckily, my whimpering inspires Dan to paddle with a fervor that gentle coaching could never summon.

“Put that paddle in the water and get in the goddamned game,” he yells, spurring us hard past Burano's teetering clock tower.

“I'm having some problems,” I say.

“Buddy, there's one solution for every problem you run into on the Vogalonga: more paddling.”

I painfully acquiesce. As we round a turn and enter a narrow boulevard of water flanked by shoreline homes, we find ourselves pointed back at the lagoon┬Śand suddenly, wondrously, the wind is behind us. We gasp with pleasure, ship our paddles, and glide along at a smooth clip.

“This is the name of the game!” cries Dan. “Jesus, I just about had a Ph.D. in headwind. That was awful.”

With the wind at our backs, our mood is transformed. Gliding away from Burano and into the broad green prairie of the lagoon, we lean back in our seats and let the wind ferry us along. On the horizon, we can see the bell tower in the Piazza San Marco, marking the finish line. The sun is warm but unoppressive, muted by a layer of blue clouds. A marvelous bird with a gorgeous green head strafes the bow and then banks off toward the snowcapped mountains in the west.

“This is absolutely killer,” says Dan. “Man, thanks so much for bringing me. I'm serious. I don't know why in the hell we don't do this stuff more often.”

“I know, I know. We should,” I say, and I actually mean it, too. This is Team Tower's other superpower, our ability to turn on a dime, from homicidal to earnestly genial. Before we've hit the island of Murano, the final waypoint before we make for San Marco, we've made a plan to head to Maine soon after we return, to paddle the Penobscot River.

It's late afternoon, and we've evidently taken so long that the motorboat prohibition has expired. Water taxis rush past, rocking us with their wakes. Our brows are crusted with salt, our clothes sodden. We look such a pitiful sight that a coast guard vessel cruises alongside us and a pair of officers ask if we're OK. We nod feebly. They pop a prosecco cork and, rather cruelly, hoist their glasses at us before moving on.

Past Murano, the tailwind subsides, making it necessary to once more paddle in earnest. The lava in my right arm has spread into my ass, and I'm on the verge of tears. I await the spiritual boost that Lino said we could expect on reaching the Grand Canal: the cheering throngs, the fanfare. But when we arrive, the crowd has gone home. On the Accademia Bridge, a drunken remnant of bellowing tourists await. Some jackass chucks a napkin-stuffed bottlecap at us, beaning Dan in the chest.

“Assholes,” he says as we pass under the bridge. “At least they didn't throw a bottle.”

The finish line is more anticlimactic than you can imagine. We've taken eight hours to complete the loop┬Śand will later learn that our visit just happened to coincide with the arrival of the worst weather in the event's history, which saw many an old hand giving up or staggering in hours later than planned. The confetti throwers are long gone, so we crawl across the canal to the narrow waterway that runs close to our hotel. Soon we pull along-side it and wrestle the boat out of the water.

Naturally, at the moment, the sky breaks open. We dismantle the Greenland II in a downpour. But, while exhausted, we are, amazingly, happy.

As I finished packing up the boat, Dan nips into a shop and returns with two cans of cold Italian lager. We eagerly crack them, and he puts his arm around me, raising his can in the pelting Venetian rain.

“To you, the captain, the pecker in chief!” I hear him say.

“Pecker?”

“Paddler,” he says. “Paddler in chief.”