YOU’VE NEVER been here. Of that I am reasonably certain. And I know you’ve never sea kayaked here, because we were the first. But if you go, one thing’s for sure: You won’t get lost on your way to the put-in. In Australia’s Cocos Islands you can, quite literally, walk off the plane, carry your folding sea kayak 100 yards to the water, assemble it, and paddle off—no need to make reservations, rent a car, or secure a permit. But first you have to get here.

Know Before You Go

Modern-day Niña and Pinta: the author’s and photographer’s kayaks beached on Pulu Beras

Modern-day Niña and Pinta: the author’s and photographer’s kayaks beached on Pulu Beras

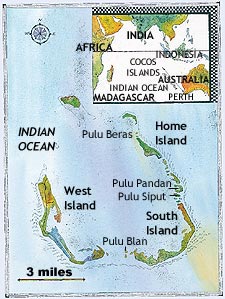

To arrive in the Cocos, fly to the middle of nowhere and hang a left. The 27 isles (only two of which are inhabited) form an atoll in the northeast corner of the Indian Ocean and lie 1,620 miles northwest of Perth. Photographer Paul Kerrison and I arrived in April, intent on paddling among the uninhabited islands that horse- shoe around the barracuda-and-bonefish-filled lagoon. We would camp. We would fish. We would do little else.

Half of the 120 residents of 2.4-square-mile West Island are waiting outside the airport when we arrive. With only two flights a week, greeting new visitors to the Cocos is a social occasion rivaled only by good surf or happy hour. Twelve-year resident Terry Washer meets us on the ground and gives us a tour of the settlement. This takes about 20 minutes. Among the establishments are a restaurant, a bar, a dive shop, a small school, a supermarket, and some medical facilities. All the buildings are one story. Washer, 52, is owner of the Cocos Surf Shop (a glorified souvenir stand with little in the way of actual surfing gear), and one of a handful of volunteers who assist Cocos tourists (currently arriving at the dizzying pace of ten to 15 a week). He is a middle-aged version of the prototypical Australian surf bum: blond and tan. The man is long past the point of taking life any other way but easy. While walking to the shoebox-size tourism office, I see through the palm trees what appears to be an impressive left surf break curling up about 90 feet from shore.

“Looks like some nice waves,” I say.

“We don’t talk about the surfing here,” Terry replies.

The message is friendly but clear: We know you’re here to write about us, but that doesn’t mean we want our surf splattered all over the pages of your magazine just so some billionaire can come build a casino with a view. It is a shared, not altogether secret, sentiment on the Cocos—we got it good, let’s keep it that way.

At the tourism office, Terry shows us an aerial map of the islands and we put together a rough five-day itinerary. We’d spend the first night on a tiny nub southeast of West Island called Pulu Blan, about an hour’s paddle away. We’d return to West Island on day two, resupply with food and water, and paddle seven miles across the lagoon, spending the next two nights on any of the small islands on the southeast side of the atoll. Our fourth and fifth nights would be spent on either Home or West Island, depending on time, tide, and muscle soreness.

Having hatched a plan, we walk over to the local market, a concrete, two-aisle affair filled with the scent of fresh produce that, like us, has recently come off the plane. We grab granola bars, PB&J, and a loaf of bread.

“I’m sorry, you can’t buy that,” says the clerk, pointing to the bread. I turn the loaf over and see a name written on the side of the paper bag. Fresh bread, we are told—fresh anything, for that matter—is a commodity ordered in advance. We may purchase only the frozen variety. So we do, and 30 minutes later we’re on the water, the setting sun warming our shoulders as we paddle wide-eyed across the turquoise expanse toward our first campsite, about two miles away. Everything Paul and I know about the Cocos Islands at this point could be scribbled on a gum wrapper, with room to spare.

THE NEXT MORNING we dally around our makeshift campsite, a stretch of searing-white sand ten feet from the water that we share with a few dozen palm-size crabs. We pay no mind to the rapidly dropping tide—a crucial mistake that turns our first morning paddle into a sunbaked trudge across the flats. When we finally reach the beach back on West Island, the temperature is in the nineties and we are dying for nothing more than a cold Pepsi. But that would be our second mistake. The sign on the door of the restaurant tells the story. Lunch: 12 to 1. We are late and thirsty.

After tracking down drinking water and waiting for the tide to rise, Paul and I head back out across the bay, intent on reaching the east side before dark. But two windy hours later we are only halfway. It is then that we remember something Terry’s daughter Emma, 21, had said back in the tourism office as we scanned an aerial photo of the lagoon.

“You don’t want to paddle across those,” she said, pointing to dark spots in the water. “Those are black holes. That’s where they live.”

They are tiger sharks, second in size and ferocity only to the great white, reaching a length of 18 feet and weighing more than 2,000 pounds. At the time we laughed it off as superstition, but we later heard credible talk of at least one, possibly two, resident tigers that occasionally take refuge in these holes. Paddling across these freaky, deep patches of indigo, where the bottom drops abruptly away to reveal nothingness, is so unnerving that I soon stop looking down altogether. It is during one of these hole crossings that I hear a yell from Paul that freezes me on the spot. Looking in his direction, I see an enormous white fin, five times the size of the reef-shark fins we’ve been seeing all day, slicing swiftly through the water just beyond the bow of his boat. I’ve never felt so instantaneously terrified in my life. When the fin disappears, Paul suggests that I paddle up behind him so that we can present a much larger silhouette to anything looking up from below.

“Why do I have to paddle in back?” I ask.

“Because that’s the half they bite off,” he replies.

In retrospect, Paul and I both believe that we really saw the underside of a large manta ray. At least, that’s what we’re telling ourselves.

AFTER ANOTHER close call with the tide, we finally reach the island of Pulu Pandan, where we pitch our tents in the dark under a dozen coconut trees and are soon asleep, exhausted from our four-hour crossing. The next day is not pleasant. A burly storm coming straight from Java builds slowly throughout the day, and by late afternoon we are treated to 60-mile-per-hour gusts, with 700 miles of ocean fueling the waves from behind. A direct hit by a cyclone would be devastating to the Cocos, but with a total land mass of six square miles, the chances of that are as remote as the islands themselves. Yet many have come close, including Harriet in February of ’92, which pushed to within six miles of shore and sent wind speeds to 101 miles per hour. Today it’s far too gusty to paddle so we spend much of the day attempting to catch dinner in an arm of the lagoon 20 feet from camp. Paul finally reels in a small sweetlip and we cook it while taking refuge from the storm on the deck of one of the small fishing huts the Cocos Malay people have built throughout the islands. Amazingly, I get cold.

We wake the next morning to the sound of a small outboard pulling up to shore. Two men get out, check to make sure we haven’t disturbed their hut, and hand-dig half a dozen crabs from the sand before heading back out to bigger water. The storm has cleared and Paul and I are soon on the water ourselves, paddling two miles toward the Cocos Malay settlement on Home Island.

Cocos Malay people make up about four-fifths of the atoll’s population of 500. They are descendants of the original inhabitants, who were imported as slaves from throughout Indonesia to help cultivate the coconut-oil business of John Clunies Ross, a Scottish sailor who settled in the Cocos in the late 1820s. He and his family ran the islands for the next 150 years, until selling them to Australia in 1978. The islands are now managed by a locally elected governing body called the Cocos Islands Shire Council, composed of members from both Home and West Islands. Despite the integration with Australia, the Cocos Malay have kept intact one of the world’s least-known cultures—tourists weren’t allowed on the islands until 1991, unless they made arrangements in advance for a place to stay.

The sound of prayers floating off Home Island makes its way across the water as we approach. It is the second of five prayers the devout Islamic Cocos Malay people say daily, and the beauty of the old language removes the soggy memories of the previous day. We beach our boats among the jukongs, elegant wooden sailboats, lining the shore, evidence of the islanders’ impressive woodworking skills. I take a short walk along the narrow, palm-shaded streets and notice that the buildings of Home Island have an orderliness to them that brings to mind a military base—not surprising considering the Cocos were used during World War II for that very purpose, serving briefly in 1945 as home to more than 8,000 Allied troops from Britain and India. The people here are dressed brightly, in reds, oranges, and yellows. I see a small slice of America—a Michael Jordan tank top on a nine-year-old boy.

After a whirlwind tour of the island that included everything from taking in a sailing race to watching a circumcision ceremony, we decide that we have no desire to paddle over the black holes again. Instead, we load our kayaks onto the 50-foot ferry shuttling people back across the lagoon.

YOU’D THINK residents of a place so far removed, with a total land mass smaller than that of some American malls, would socialize among themselves whenever possible. Not so. The Cocos Malay on Home Island and the Aussies on West Island operate in dual worlds separated physically by a seven-mile lagoon and culturally by religious differences and nearly 200 years of isolation. Though interisland camaraderie is on the upswing, the two groups are content to keep to themselves. “We’re starting to do a little more together but they’re very protective of their culture,” says one West Island resident. “It’s hard socially because they forbid alcohol—and we’re Australians, so we drink like bloody fish.”

Later that night, while drinking with the Aussies on West Island, we are introduced to their culture, including a unique style of tequila shot that involves drinking only after squeezing the lime into your eye and snorting the salt up your nose. We leave the next morning as most people leave any tropical island: reluctantly, with a promise to return. When I ask Terry what the greatest thing has been about living on the Cocos for more than a decade, he says something about watching his two daughters grow up here.

“Anything else?”

He doesn’t answer, just smiles and nods toward the waves breaking nearby.

“I understand,” I say. “We can’t talk about that.”

Boats: You’ll need a folding kayak if you want to island hop. We brought one Alu-Lite from Klepper ($1,980; 800-500-2404; ) and one Kahuna from Feathercraft ($2,300; 604-681-8437; ). Each comes with a carrying case, weighs less than 40 pounds, and easily fits within most airlines’ baggage restrictions. My favorite break-down paddle is the carbon two-piece Wayfarer from Epic Kayaks Inc. ($385; 206-523-6306; ).

Fishing Gear: You’ll want two travel rods: an eight-weight for bonefish and a 12-weight for giant trevally, barracuda, and black-tipped reef sharks. I brought an 890 RPLXi from Sage ($525; 800-533-3004; ) for the former, and a Scott STS 9012/3 ($570; 800-728-7208; ) for the latter. Pack steel leaders and plenty of saltwater-variety flies.

Clothing: Bring only pants or shirts made from quick-drying material, like nylon Supplex. My favorites: Cloudveil‘s long-sleeve Cool Shirt ($75; 888-763-5969; ); Tarponwear‘s Imperial Cargo Pant ($66; 800-291-9402; ), and Ex Officio‘s Double Haul shorts ($49; 800-644-7303; ).

Camping Gear: We each brought a tent, which came in handy during the mini hurricane. Mine was a Solitude from Mountain Hardwear ($195; 800-953-8375; ), and Paul’s was a Clip Flashlight CD from Sierra Designs ($189; 800-635-0461; ). We both brought the lightweight (2-pound, 3-ounce) Polarguard 3D Cross Mountain sleeping bag from Big Agnes ($129; 877-554-8975; ).

The Cocos Islands offer everything you need—surfing, scuba diving, fishing, and sea kayaking—and nothing you don’t. It may be pricey to fly there, but once you arrive, you can easily get by on less than $50 a day (including bar tab). The only golden rule is this: Be polite and ask permission from the residents before you pitch a tent on any of their pristine blond beaches.

Getting there: Round-trip flights from Los Angeles to Perth on Air New Zealand (800-262-1208; ) cost $1,850-$2,100 per person. Two flights per week on National Jet Systems (book through Island Bound Holidays, which can also arrange accommodations, 011-61-8-9381-3644; ) depart from Perth for the five-hour trip to the Cocos Islands. Round-trip airfare runs about $872 per person.

Where to stay: Camp free of charge virtually anywhere, but you need to run your plans by the Cocos Islands Shire Council first (011-61-8-91-62-6649). There are only five lodging options, all on West Island. Try the recently renovated Hermit Lodge (doubles US$340 per week; 011-61-8-9162-6515; ), which has two apartments and a four-bed, bare-bones, backpacker-style bunkhouse, and is just yards from the beach. The three Balinese-style Cocos Cottages (doubles, US$548 per week; 011-61-8-91-9244-3801) sleep four people and have giant verandas.

Food: Think PB&J and grilled burgers: There’s only one grocery store and one restaurant, both on West Island and both open only when they want to be. To stave off those hunger pains, take your fly rod and head to the flats to fish for trevally, sweetlip, and barracuda.

Getting around: You can rent a car, bike, or scooter on West Island, but you don’t really need any of them. A small bus picks passengers up from the dock at the north end of the island, where you can take the free 25-minute ferry ride to and from Home Island four times daily. Plan on spending at least one day on Home Island, but respect the Muslim residents by wearing conservative clothing. Terry Washer at the Cocos Island Tourism Association (011-61-8-9162-6790; info@cocos-tourism.cc) can answer any questions regarding diving, surfing, fishing, and camping. For further information visit .