LET ME JUST SAY RIGHT OFF THE BAT that I didn’t have any illusions about doing well in the Blackburn Challenge. Or at least not that many. After all, the Blackburn, held each year in mid-July, is the longest open-water race on the East Coast, a 23-mile marathon circumnavigating Cape Ann, the rocky thumb of Massachusetts that juts out into the Atlantic north of Boston. While the beginning and end of the course are in protected waters, the bulk of it—about 20 miles—is in open sea, where anything can happen. Tough people row the Blackburn, and not all of them finish it. What kind of threat was I, a guy from New York who’d rowed crew in college but now got out just a few times a month on the placid waters around Shelter Island?

Blackburn challenge

Not long after arriving in the old fishing port of Gloucester, I stumbled on the Crow’s Nest, the grungy locals’ bar immortalized in The Perfect Storm. I was tempted to go in for a beer but didn’t, fearing the inevitable conversation: “Did you say Shelter Island?” “Actually, I live in Greenport, but it’s near Shelter Island, you know, out on the East End of Long Island.” “Hey, boys, whoo-whee, we got somebody here from Shelter Island!”

Down at the Gloucester High parking lot, launch site for the Blackburn, hard-bitten scullers and paddlers were unloading battered shells and kayaks from their cartops, all the while staring anxiously at the sky. Low, gray clouds were streaming in from the northeast, and the forecast was calling for a major low to pass overhead during the night.

The first guy I talked to was Dana Gaines, 46, a Blackburn veteran who, rowing a two-man shell in 2001, had set the course record of two hours 21 minutes. “I’d say out of ten years, seven are pretty nice, two are bad, and one is awful,” he said when I asked him about the conditions. “Tomorrow’ll probably be one of the bad.”

But the next morning, things seemed OK. Though the wind was blowing out of the north-northeast, the Annisquam River, whose snaking channel we would follow for the first two miles of the course, looked reassuringly flat. The race was set to go off at 7:30, shortly after high tide, the idea being to ride the ebb north to Ipswich Bay and then on to Halibut Point, at the northern tip of the Cape Ann peninsula. After a sweeping turn back to the south, we’d follow the rocky coastline all the way to Eastern Point, at the head of Gloucester Harbor. From there it was a short jog north to the finish line, off Gloucester’s main beach.

By the time I launched, there were about 150 people on the water, split into two main camps—backward-facing rowers and forward-facing paddlers. Eyeing one another warily, we exchanged cursory nods and slowly grouped ourselves into smaller subcategories. The rowing contingent went first, led by four venerable Banks dories, the traditional high-ended, flat-bottomed boats emblematic of Yankee seafaring. After that, at five-minute intervals, came waves of increasingly speedy fixed-seat rowing craft—home-built plywood skiffs, rugged surf boats, fragile wherries, multi-oared gigs. Last among the rowers was my category: sliding-seat racing singles—skinny, tippy fiberglass shells nearly as long and light as those rowed in the Olympics.

As the one-minute warning sounded, I felt an unexpected surge of confidence. True, there were two fast, smooth-stroking guys who were probably out of my league. But the rest of the field of seven looked vulnerable. One rower about my age (45) was clearly fit, but his boat was a couple of feet shorter than my 24-foot one, and thus theoretically slower. There was an aging graybeard (he would wilt down the stretch, I figured), a petite, if determined-looking, woman, and a fat guy in a life preserver. The dorky vest, I knew, would prevent him from bringing his oars all the way into his body, and thus from completing anything close to a full stroke. Plus, it looked ridiculous—nobody rows in a life preserver.

So it was that, as the starter barked out a few final commands, I mentally assigned myself a podium finish. Not bad for my first stab at the Blackburn!

A CENTRUY AND a quarter ago, Gloucester was the leading fishing port in the world. Gloucestermen departed in racy schooners for “the Banks”—the fish-rich but notoriously storm-tossed shoals that stretch from Cape Cod to Newfoundland. Once there, they fanned out in two-man dories to set trawls, longlines studded with multiple baited hooks, for cod and halibut. Small boats launching from speedy, lightweight mother ships: It was an ingenious technology, but also incredibly dangerous. In Gloucester’s heyday, the 25-year stretch from 1866 to 1890, a staggering 382 schooners and 2,454 men were lost at sea.

But for his strong back and superhuman will—in a story that’s become legend in these parts—Howard Blackburn would undoubtedly have joined those doomed legions. In January 1883, the 23-year-old Nova Scotian signed on to fish halibut aboard the Gloucester schooner Grace L. Fears. Two weeks later, a sudden, blinding blizzard blew in, and he and his dorymate, Thomas Welch, became separated from the Fears. After a desperate night in the tiny open boat, the two decided to make for the coast of Newfoundland, some 60 miles away.

It was a terrible ordeal. On the second night, Welch gave up the oars, lay down, and froze to death. Meanwhile Blackburn, frantically seeking to empty the boat after a wave had swamped it, accidentally bailed his own mittens over the side. Nevertheless he rowed on, his hands eventually freezing into stiff hooks. After five days at sea without food or water, he made the coast of Newfoundland, where a homesteading family took him in and nursed him back to health. In the spring, Blackburn returned to an astonished Gloucester, minus his fingers, half of each thumb, and most of his toes. He quickly became the toast of the town and, once the national press picked up the story, the sea hero of the era.

“Howard Blackburn is still very well remembered in Gloucester,” says John Spencer, cofounder of the Cape Ann Rowing Club, the group that has run the Blackburn Challenge since its inception, in 1987. “Dorymen were the hardiest of fisherman, and he was the toughest of a tough breed.”

THE RACE STARTED pretty much the way I’d expected: The two fast, smooth guys bolted into the lead while the rest of us hung together in a loose pack. It was fun to call out obstacles—”Hey, you’re about to hit that buoy”—and look into the picture windows of elegant waterfront homes. Far more satisfying, however, was picking off the slower vessels that had started before us: the lumbering dories, skiffs, and wherries.

As we approached the lighthouse that marks the end of the Annisquam River, I was sitting comfortably in fourth place among the sliding-seaters. Then we came around the corner into Ipswich Bay, and the real race began.

The wind was blowing hard, driving big waves before it and occasionally pushing whitecaps over their tops. Suddenly, without warning, a wave broke directly over the bow of my boat. It wasn’t really scary—the boat is a sealed, watertight tube, and even the little hollow where my feet are braced has a self-bailer, a sort of one-way drain. But it was still a shock. Back home on Peconic Bay, the only time I ever filled the footwell was when giant powerboats waked me at 20 knots. A minute later I took another wave, and felt a growing sense of alarm. I was soaked, barely moving, and still a good 19 or 20 miles from the finish line.

Incredibly, it got worse. The tide was running in direct opposition to the wind, and at each of the several rocky headlands that lie between Annisquam Light and Halibut Point, the sea pitched up in the most absurdly chaotic mess—a “potato patch,” as sailors sometimes call it—short-period, six-foot-high waves that seemed to come from all directions at once. The footwell was perpetually swamped now, my forearms were pumped from choking the oars in a death grip, and dime-size blisters had begun to well up under the calluses on my palms.

It was at one of these junctures—the second or third potato patch, I think—that I noticed another racer 20 or 30 yards to starboard. It was the sole woman entered in the sliding-seat category—Kinley Gregg, I learned later, a 41-year-old historian from York, Maine. Somehow she was rowing smoothly through the slop, gaining on me at what seemed like four or five feet per stroke. “I like the challenge of uncertain conditions,” Gregg explained to me later. “I abhor the monotony of river rowing, where every stroke is exactly like the last and the oarsman strokes along like a metronome. I say, if it’s not doing anything, it’s not water, and not worth going out.”

Head down and suffering, I barely noticed the other rowers going by. But rounding Halibut Point, I was relieved to see that at least one of them, the guy in the life preserver, was still well astern. Then, just as I turned for the long run across Sandy Bay, he made his move, flanking me 100 yards to port. I glanced over, not quite believing it. Obviously he was riding some secret ocean current that everybody but me knew about. The day’s humiliations were hardly over, though. Behind me, just rounding Halibut Point, I could see a small figure robotically chopping at the water with a double-bladed paddle—the first of the kayakers.

BACK IN 1987, at the inaugural Blackburn Challenge, all 45 of the entrants were oar-powered rowing craft. Of the 167 boats that entered last year, 131 were paddle-powered. No one’s complaining, exactly, but still—is paddling really Blackburnesque?

“The kayaks have really proliferated, and we’ve sort of grudgingly accepted them,” Henry Szostek, a 60-year-old machinist who builds his own boats and has never missed a Blackburn, told me. “But I don’t understand it. I wouldn’t get in any boat you have to know how to operate with your head underwater.”

Of course, when it comes to rowing, paddlers have their own questions. A friend of mine put it best. As I explained the mechanical advantages of rowing—the oar as lever, the oarlock as fulcrum, the sliding seat as a tool for harnessing leg power—he nodded, then frowned. “But how do you know where you’re going?” he said.

You don’t, always, but maybe that’s part of rowing’s appeal. Paddlers, if I may generalize, are forward-looking people, bouncy and optimistic—literalists who focus on their destination the way an ape focuses on a banana. Rowers are backward-looking, complicated, and wistful—romantic grinders who pull for a goal without ever quite seeing it clearly. Face away from what you want, the sport teaches. Put your back into it and pull hard, and someday you’ll get there.

For me, the essential difference between the two disciplines was driven home the night before the race, when the Cape Ann Rowing Club hosted a talk by two ocean rowers, Tom Mailhot, 44, and John Zeigler, 54. A year earlier, the two had raced 35 other crews 2,900 nautical miles across the Atlantic, from the Canary Islands to Barbados. Something about the way Mailhot recounted their time—”58 days, three hours, and 54 minutes”—made the crowd laugh. But the venture had clearly exacted a steep price, wiping out Mailhot’s bank account, wrecking Zeigler’s marriage, and, they freely admitted, taking them right to “the psychological edge.” “Will you do it again?” someone asked. “Next question,” Mailhot snapped.

In a bow to the paddling contingent, the Rowing Club had also invited a kayaker to speak, a 44-year-old flatwater star named Greg Barton. At the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea, he’d won two events in one day, the 1,000-meter doubles and the 1,000-meter singles, each by a margin of less than a foot. Barton preached the gospel of positive thinking, spiced with the occasional sarcastic zinger. “A lot of people came up to me after the second race and complimented me on my good luck,” he said, “and I was like, ‘Yeah, after 18 years of training, today’s my lucky day.’ “

I should not have been surprised, then, to discover that the kayaker bearing down on me the next day, as I flailed my way south from Halibut Point, was the legendary double gold medalist himself. Yet I was surprised enough that I lost track of the waves now rolling in on my beam—a dangerous blunder in a narrow boat. Before I quite realized what was happening, one rose up in an oddly shaped peak and slapped me on the side of the head. The boat rolled to starboard and I pitched face first into the green Atlantic.

When I surfaced, Barton was a few feet away. “Is everything all right?” he asked. “Do you need any help?” “Maybe a few lessons,” I said, trying to remember the approved technique for hoisting myself back into my boat. “But no, really, I’m fine… . Please, keep going.” “Well, OK,” Barton said doubtfully. “There’s a chase boat right behind me.”

THE HALFWAY POINT of the Blackburn Challenge is the narrow channel between Cape Ann and Straitsmouth Island. I reached it at the two-hour mark, called my bow number to the committee boat that was anchored there, crammed a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup into my mouth, and rowed on.

The second half of the race should have been much easier than the first. I was heading southwest now, with a tailwind and a following sea, and in theory I should have been able to surf merrily down the waves like the kayaks that were now passing me with annoying regularity. On rough days at home, I’d practiced the technique and actually gotten pretty good at it. But here, every time I’d get up to planing speed, the boat would invariably veer off course and stall. It felt sluggish and unresponsive, and I began to fear that I was somehow taking on water and might even be sinking.

Two anxious miles later, having spied a pocket beach amid the rocks, I turned for shore. There, I removed the little cork drain plug in the bow and swung the boat up over my head, expecting a torrent of water to rush out. Nothing—bone-dry. Then I saw the problem: The boat’s skeg, or fin, essential for maintaining a straight-line course, was flopping loosely in its groove on the stern. During a pre-race check that morning, it had seemed a bit wobbly, so I had pulled it out and reseated it with some “miracle adhesive.” The miracle, I suppose, was that the skeg was still attached at all.

What to do? It was either leave the boat in the dunes and make the long walk of shame back to Gloucester, squelching along in my reef socks, or get back in and claw away with my hamburgered hooks, like old Howard B. himself. “Well, all righty then,” I said (I’d reached the point where I was talking to myself out loud), “if you’re gonna put it that way …”

The Blackburn wasn’t quite done with me. I struggled badly rounding the jetty at Eastern Point, the entrance to Gloucester Harbor. The tide was still ebbing furiously and the course lay once again upwind, and for a few minutes I amused some onlooking fisherman by not making any headway at all. Then, suddenly, I broke free of the current’s clutches. The high steeples of Gloucester drew closer with every stroke, and as I came up under the lee of the land, the waves began to diminish.

Flat water! I took a “power 20″—20 strokes at full throttle—and looked over my shoulder just in time to see the mountainous form of the Ocean Club, a 145-foot floating casino bound for international waters. Given the way my day had gone, I half expected something terrible to happen—another capsize or a broken oarlock. But I was a Blackburn veteran now, or almost. I turned to port, cranked smartly on the oars, and got the hell out of the ship’s way.

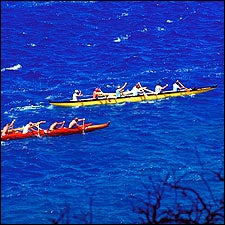

Five minutes later, I was dragging myself and my shell up on the beach in downtown Gloucester. Most of the early finishers were still there. Dana Gaines and Joe Holland, rowing a wooden double scull, had posted a 2:36, the fastest time of the day. They were followed by two six-man outrigger canoes, another double scull, and Greg Barton, the first solo finisher, just five minutes back in 2:41. One of the two smooth-stroking guys had won my category, sliding-seat racing singles, in a time of 3:05, but Kinley Gregg, the lone female sculler, had overtaken the other for second place in 3:09. My time was 4:04. True, I’d beaten a few of the fixed-seaters. But overall I’d finished 90th, and in my category I was DFL—dead last.

I spent a few minutes pretending to tinker with my boat, then joined the circle where the other sliding-seaters were trading stories. When my turn came, the fat guy in the life preserver—he was still wearing it—looked at me and laughed. “Ah,” he said. “Your first Blackburn.”