EASTERN ONTARIO IS SILO COUNTRY, a canvas of flat farmland, shambly barns, and hoof-stamped fields stretching in all directions. Except for a few gradual rises and dips, there’s nothing to suggest that one of Canada’s largest rivers roars through this blank landscape, nor that this river—in springtime, the color of root beer shaken to a froth—funnels off a steep ledge and boils into one of the largest standing waves in the world, a feature both feared and revered by the world’s best whitewater kayakers. On a too-cold Tuesday evening in early May, less than a week after the Ottawa River surrendered its last ice floes, 175 of these kayakers have come to battle the monster wave known as the Greyhound Buseater in the 2007 World Freestyle Kayak Championships.

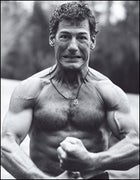

Eric Jackson

Jackson on the banks of Tennessee's Caney Fork River

Jackson on the banks of Tennessee's Caney Fork RiverEric Jackson

E.J. with Dane and Emily after a day of kayaking

E.J. with Dane and Emily after a day of kayakingEric Jackson

E.J. at rest in the Jacksons' home away from home

E.J. at rest in the Jacksons' home away from homeEric Jackson

The Jacksons—Eric, Emily, Kristine, and Dane—with dogs Target and Roxy in the family RV

The Jacksons—Eric, Emily, Kristine, and Dane—with dogs Target and Roxy in the family RVBy far the most famous on the roster is Eric “E.J.” Jackson, the big daddy of freestyle and—by his own estimation and nearly everyone else’s—the most decorated paddler in history. The three-time world champion is father and coach to two enormously talented pro kayakers as well as president of Jackson Kayak, the country’s fastest-growing whitewater-boat manufacturer. At 43, he’s the patriarch of his own paddling dynasty, with an XXL personality and, some say, an ego to match. He’s here with his wife, Kristine, 37, and their superstar spawn, 17-year-old Emily and 13-year-old Dane, to attempt the first-ever Jackson world-championships sweep—or, in less modest terms, total global domination of freestyle kayaking.

The odds are stacked in their favor, and the mood is optimistic—if chaotic—at Jackson HQ on the eve of the competition. The family has taken up residence in a rented clapboard farmhouse, half a mile from Buseater. Their giant white RV, with JACKSON KAYAK emblazoned across it, is parked in the driveway, and boats of every color are scattered across the lawn. E.J., Dane, Emily, and Emily’s boyfriend, 18-year-old Jackson-sponsored paddler Nick Troutman, are just back from their final practice session and are slinging drytops and soggy spray skirts over the front-porch railing.

“Buseater’s in, and it’s huge!” E.J. cries excitedly, his bristly black hair still wet from the river. Compact and muscular at five foot six, he buzzes around in a blur of nerves and boyish, unfiltered enthusiasm.

Inside, a dozen Jackson-sponsored paddlers—some here to compete, others simply to support the tribe—are huddled around laptops, editing the company’s new promotional DVD. Kristine has left for an event organizers’ meeting, so dinner is self-serve and not your standard high-performance fare: potato salad, Lay’s straight from the bag, plain Wonder Bread buns, root beer, and a bowl of grapefruit.

E.J. skips dinner and holes up in the RV to plot his freestyle routine on a computer spreadsheet. In tomorrow’s preliminary round, he’ll have four 45-second rides on Buseater to churn out as many acrobatic moves as possible, some of which—like the McNasty, a twisting aerial somersault—he’s minted during his 15-year freestyle career. Each trick earns points for execution and difficulty, and E.J.’s program helps him calculate which combination of moves will generate the highest score possible.

“I do get nervous in the early rounds,” E.J. admits when he emerges an hour later. “You don’t have to go all out; you just have to stay in the game. I do best under pressure, when it’s win or lose.”

To psych himself up, he finds a seat at the dining-room table with the others to watch the promo video. “Check that out!” E.J. cackles as his onscreen self does a backflip on Uganda’s White Nile, where he and the Jackson pack trained for five weeks last winter. “Sweeeeet!” Dane, who’s been lounging on a trundle bed in the living room playing Xbox, hops over in his sleeping bag to watch.

Later, after E.J.’s gone to bed in the RV, the non-Jacksons sit around the kitchen table discussing their boss’s prospects for the competition. “His practice runs today were disastrous,” whispers Clay Wright, 40, a pro boater and Jackson Kayak field marketer, arching his eyebrows for effect. “He looked foreign to me out there.”

It’s not a good sign, given the herd of hungry young paddlers who want nothing more than to take down the defending champ and crush his legendary bravado. But for E.J., there’s more than another victory at stake. He’s built a business—and a family life—around his paddling prowess. Another win at the worlds will boost his cachet, which is good for his company—four years old and on the verge of profitability—and, in turn, good for his wife and kids. It’s a precarious arrangement, but E.J. is unfailingly upbeat.

“I absolutely want to win, because all the indicators are that I should win,” he tells me at one point. “Nick will do wonderful. Second place will be fine for him.”

MENTION E.J. TO OTHER KAYAKERS and you’ll get a mix of admiration and grumbling—often out of the same mouth. From one perspective, E.J.’s living a charmed life that most of us only dream about: He travels the world with his family, winning nearly every event he enters. From another, he’s a competitive showboat who’s constantly hogging the spotlight.

“E.J. is way too intense,” says Patrick Camblin, 25, an accomplished pro paddler. “That’s not fun, but he pretends it is. Dude, get over it!” But when I ask if E.J.’s passion for the sport seems genuine, Camblin softens. “Fair enough,” he replies. “If someone is content with who they are and what they do, good on them. I guess that’s happiness.”

“There is an arrogant cockiness about him,” says Ken Hoeve, field-marketing manager for rival brand Dagger Kayaks. “But it ain’t braggin’ if it’s true. People who diss him are just jealous.”

E.J. seems proud of his reputation. “I don’t ever sacrifice for anything,” he told me one night about a month before the freestyle championships. It was after 10 p.m., and he was sprawled sideways across an armchair in the Jacksons’ 3,500-square-foot log home near the Caney Fork River in Rock Island, Tennessee, about 100 miles southeast of Nashville and just a mile from one of the best playboating holes in the Southeast. The house, finished late last year, was a stretch for them financially, but it gave Emily her own room—a luxury after six years of living in the 31-foot RV, which the Jacksons drove to rivers around the country so E.J. could paddle full-time.

“I live the life I want to live,” E.J. said, practically hollering into the echoey house. He speaks loudly and reads lips to compensate for the 50 percent hearing loss he’s had since childhood. “I do what I want. I run the business the way I want. I go kayaking when I want. People who compromise aren’t creative.”

Or maybe they’re just less driven. E.J. has spent the past decade designing his perfect life, systematically ranking his top priorities and jettisoning anything that threatens his goals. Of course, he’s gotten plenty of flak for cramming his wife (number one on his list) and kids (number two) into a motor home in order to devote himself to paddling (supposedly number three). “Any way you look at it, what I do is super-selfish,” he admitted. “But I also get to spend tons of time with my family and give them great opportunities.”

Kristine, the only Jackson who doesn’t kayak, is more realistic about her place in the peculiar calculus of E.J.’s life. “You have to embrace your spouse’s passions or you’re doomed,” she says. “I’ve always understood that kayaking was first. I’ve never competed with it—not in 20 years—because I’d lose.”

E.J.’s whitewater obsession dates back to 1979, when he was 15 and a state-champion swimmer in New Hampshire. His dad bought him a kayak, and E.J. taught himself to paddle on a river near their home. At the time, whitewater kayaking was a little-known sport that involved slalom racing downriver between gates. “I got really good really fast, and I liked that,” he recalls. “Nobody ever showed up who was any better.”

In 1984, at 19, E.J. transferred from the University of Maine to the University of Maryland to try out for the U.S. Canoe and Kayak Team, which was centered in Potomac. It took him five years to make the cut, and in the meantime he ran out of cash and dropped out of college. He met Kristine in 1987, when she happened to attend a race in Vermont; the following year they married. By 1990, when Emily was born, E.J. was competing full-time, and they were constantly broke. He pawned his camping gear to buy diapers and trolled pizza parlors near their rented Bethesda home for unclaimed pies. “Kristine hated the whole concept,” E.J. says, “but she never stopped me.”

The next few years were iffy for E.J. He finished 13th in slalom at the ’92 Olympics, in Barcelona, then failed to make the U.S. team the next May, just weeks after being reprimanded by U.S. Canoe and Kayak authorities for panhandling—while wearing his Olympic warm-up uniform—on a busy Washington, D.C., street. At the same time, he was making his name in freestyle, or playboating, which took off in the early nineties. E.J. seemed better suited to this acrobatic style of kayaking, in which paddlers perform tricks on waves and swirling whitewater hydraulics, or holes. A member of the first U.S. freestyle team, he won the 1993 world title in October—a welcome break, especially since it came just weeks after Dane was born three months premature, weighing one pound ten ounces, with 70 percent hearing loss. “He was born into pain,” says E.J.

E.J. continued playboating, but he didn’t quit slalom racing entirely. There’s never been much profit in kayaking—a top paddler today might bring home $2,500 a year in prize money, plus $20,000 or so in sponsorship earnings—but what little there was in the early days could be found in slalom. Unlike freestyle kayaking, slalom also offered the potential for Olympic glory. But things hit bottom in 1996, when E.J. failed to qualify for the Atlanta Games. “I was supposed to win the Olympics; forget not even qualifying,” he says. “I would have done things differently had I known I wasn’t going to make the team. The lesson was, all those sacrifices weren’t worth it.”

“It was the worst time for us,” Kristine says. “Eric was away so much, and I was doing what I thought you did to run a happy house—doing the laundry, mowing the lawn—but he couldn’t have cared less. We had this major conflict going on, and there was no way around it.”

In early 1997, Kristine called a family meeting. “We figured out that we should each get to have one really important thing,” she says. “Mine was being with the kids 100 percent, and E.J.’s was paddling.” It was her idea to give up the house and move full-time into an RV so the family could be together while E.J. competed on the nascent freestyle tour. E.J. had been working for freestyle pioneer Wavesport, designing some of the first modern playboats—shorter than slalom kayaks, with flatter bottoms styled for surfing—and the company agreed to let him work, and paddle, on the road.

“It was all fixed,” E.J. says. “Immediately we were the happiest couple. It took the pressure off, and I started to win again. Family life was perfect.”

“I NEED A THREE-LETTER WORD for station,” Dane said on my first morning in Rock Island. He’d just come back from a training session on the Caney Fork and was sitting cross-legged and shirtless in the living room, working on a lesson in his eighth-grade textbook, The Growing Vocabulary: Fun and ���ϳԹ��� with Words. The exercise felt more game show than homeschool, and Dane was relying heavily on audience participation.

“Man, this is hard,” said Dane. “How about ‘to cook slowly, five letters.'”

“I think you mean six letters,” suggested Nick, who lives with the Jacksons and occasionally tutors Dane. “Try simmer.”

“Simmer is a word?”

Dane’s 13, but at four foot six and 71 pounds, he looks more like ten. Like his dad, he’s ripped, only on an even tinier scale, with apricot-size biceps, toothpick calves, and actual pecs. He was three when the family moved into the RV, and, along with Emily, he’s been home-taught his whole life.

A buoyant little pinball propelled not by ego but by pure, guileless joy, Dane ran his first Class IV rapid a month before his third birthday; when he tipped over, E.J. rolled him up by hand. Emily—who is a carbon copy of Kristine, with thick, chocolate-brown hair and a swimmer’s build—inherited her father’s competitive spirit. “Emily sizes up the other paddlers and does everything she can to make sure she’s better than them,” says E.J. “Dane’s less externally motivated. He just loves to kayak.” Which is to say, the Jackson kids take after their dad in their own ways, two halves to E.J.’s paradoxical whole: On the water, E.J. is fluid but controlled, more a technician than an artist.

He trains relentlessly—several hours twice a day on the Caney Fork—and last winter on the White Nile he and the rest of the Jackson team staged mock world championships, judging each other’s moves and crowning victors. While younger paddlers (Dane included) experiment with risky combo maneuvers—like a McNasty that morphs into a sideways-flipping roundhouse—that can cause them to wash or “flush” off the back of the wave, E.J. sticks to his dependable arsenal of high-scoring moves and muscles through them with the precision of a figure skater. “His tricks aren’t fancier or flashier than his competitors’,” says Clay Wright. “He just throws down more of them.” E.J. doesn’t disagree: “Most of my successes come from being last man standing.”

Despite his own obsessive focus, E.J. insists he didn’t push his kids into kayaking. “We’ve never given any indication that we expect them to kayak,” he says. “In fact, I thought that if they did, it would be that much less kayaking for me.” The kids started paddling seriously in 2003—Dane was eight and Emily was 12, and E.J. was their coach—and not long after began racking up impressive showings on the junior playboating circuit. Dane finished first among junior men at the U.S. team’s 2006 time trials on the Ottawa; Emily won the 2005 and 2006 women’s open division at the Teva Mountain Games, in Vail.

Of course, in a house full of competitors, someone’s bound to have a bad day now and then, but Kristine refuses to tolerate any moping. “You’re allowed to cry for five minutes,” she says. “My job is make sure that—win, lose, or disgrace yourself—you still come back to the same situation in this family. No matter what happens, we’re still us, and we’re still great. If you have anything to complain about, you’re barking up the wrong tree.”

Neither Emily nor Dane plans on going to college, and their parents aren’t pushing that either. “I don’t see any real value in it,” E.J. says. “Of course, if they want to go, we’ll be behind them 100 percent, but right now I’d say both of them have the equivalent of a Ph.D. in kayaking.”

STARTING A COMPANY had never been part of E.J.’s master plan. The family had been living on the road for years, with few expenses and fewer responsibilities. But E.J. resigned from Wavesport in 2003 (he cites differences with the company’s owners), and Kristine saw the potential to build a small family business that their kids could eventually take over. “I definitely pushed him—that’s the proper way to put it—into doing this,” she says.

E.J., who’d been in debt for most of his adult life, convinced a friend of a friend, Tucson entrepreneur Tony Lunt, to invest $400,000 in seed money. Then he rented a 700-square-foot former laundromat in Rock Island and started sketching boat designs. From the start, he’s aimed to build high-performance boats and market them in ways that make a traditionally hardcore sport more accessible. It was E.J. who came up with the brand’s perky boat names, like 2Fun and SuperFun, and created Jackson Kayak’s mascot, a stick figure with a paddle and a goofy, gung-ho smile.

“I knew when I saw the smiley-face logo that people would say, ‘That’s not aggro or cutting-edge,’ ” says Clay Wright. “But I should have seen it coming a mile away. They’re a family; they like to paddle. They don’t care!”

E.J.’s going his own way on the R&D front, too. He uses a plastic that’s more expensive—and, he says, stronger—than what his competitors use. (Other companies have steered away from the material, claiming it’s more toxic and harder to recycle; Jackson points out that his company does recycle, by grinding up customers’ old boats for useasphalt.) E.J.’s also devised ways to construct kayaks without drilling holes in the hulls, making the crafts less leaky, and he designs boats in as many as six sizes, rather than the standard two or three. In the company’s rookie season, he created the first kid-specific kayak, the shrimpy Fun1.

To save cash and keep boat prices low, he has no advertising budget and no sales reps; retailers place orders directly with the factory. But as long as E.J. continues to win and Emily and Dane keep improving and the whole hypertalented tribe keeps making the rounds on the freestyle circuit, he believes the brand will continue to grow. “The better I am as a paddler, the better my business does,” E.J. reasons. “Bringing my family with me is good for the business and promotes kids kayaking. It’s a well-thought-out, functional package.”

In 2006, E.J. says his company sold over 3,500 boats—more, he believes, than any of his competitors—and traded up to a 90,000-square-foot building in nearby Sparta, an old Wrangler Jeans factory so cavernous that the company’s 45 employees ride cruiser bikes to get from one end to the other. He redesigned 11 boats in his fleet for 2007 and expects Jackson Kayak, which he says is now worth $4.5 million, to become profitable by the end of this year.

It’s all part of his audacious goal to dominate the $11.7 million whitewater-kayak market—and double it by 2012. Though phase one may soon be within reach, phase two borders on the absurd, even by E.J. standards. The industry has faltered in recent years; whitewater-kayak sales fell 59 percent from 2001 to 2006, according to the National Marine Manufacturers Association. Whether the drop was caused by a general economic downturn, a few drier-than-average seasons, or, as E.J. suspects, lack of corporate sponsorship for clinics and river festivals (which he says are critical to drawing new paddlers to the sport), he’s convinced that more customers are out there. He just has to lure them in with some strategic PR.

This past spring, E.J. launched WorldKayak.com, an online community offering river information, competition calendars, and boater blogs. Jackson Kayak’s posse of top paddlers spread the feel-good gospel of whitewater by teaching novices how to paddle at rivers across the country and pitching the brand directly to dealers. And then, of course, there’s the brand recognition afforded by E.J.’s cult of personality and his unbeatable record: He’s won five of the past seven major freestyle events, including the 2001 and 2005 world championships.

“Anyone who says Eric’s all about the marketing, they’re right,” says Dagger’s Hoeve. “He wants to see the sport grow. But anyone who tries to deny that he’s also in it for the fun of kayaking is wrong, because he wouldn’t be doing this if he didn’t love it. None of them would.”

“I want Jackson Kayak to have longevity and a lot of margin for error, so that Emily and Dane can make mistakes without it tanking,” says E.J. “But if I had to choose between Jackson Kayak and kayaking, well, it’s simple: Kayaking comes before the business. It’s not even a question.”

FINALS DAY ON THE OTTAWA IS BRIGHT and cloudless, the DJ’s hip-hop is deafening, and the Ottawa is raging with such ferocity it’s as though someone is blasting the Arctic ice cap with a blowtorch. To create Buseater, the river slides down an embankment and whips itself into a ten-foot-tall standing wall of whitewater known as the “pile”; beneath that is the “pit,” where the competitors launch their flips, spins, and aerials and try not to get sucked into the wave’s watery jaws.

Over the past two days, E.J. squeaked through preliminaries in fourth place and made it through the quarterfinals looking tentative and grabby, as though the fate of the Jackson dynasty hung on his every paddle stroke. But judging by the reaction of the rangy teenage shuttle driver who picks me up at the Jacksons’ farmhouse, maybe it doesn’t. “The E.J.?” he says, visibly wowed. “People are horny for his boats!”

On the river, there’s no shortage of speculation and smack talk about E.J., the usual mix of eye-rolling and begrudging awe. I catch up with Jackson Kayak pro Billy Harris, 33, who’s just been eliminated by his boss in the semifinals. “If we’re playing volleyball, where do you think Eric’s gonna put the ball?” he asks, laughing. “One hundred times out of a hundred, he’ll spike it to the weakest player. And what if it’s his daughter? He’ll smoke it into her every time!”

Rush Sturges, 22, a big-wave paddler who missed the cut in the quarterfinals, puts it more bluntly: “E.J. is a machine. He’s full-on out to win this event.”

Most people are betting on Troutman, but the Jacksons seem focused, not worried, and as the day goes on they just seem psyched. E.J. plays pumped-up stage parent, parading around in an ankle-length fleece muumuu and flashing Emily a peace sign after she wins the junior women’s division. When Dane, looking tiny but in charge on Buseater’s back, takes third among junior men, Kristine picks him up and hugs him, his feet dangling in the air. If he’s disappointed, he has five minutes to show it.

At 4 p.m. it’s time for the men’s finals. The five remaining kayakers—including Troutman and E.J., who’s the oldest by 15 years—have three chances each to land their biggest moves; the paddler with the single highest-scoring ride wins. E.J., bobbing in the eddy in his canary-yellow Jackson All-Star, blows a kiss to Kristine, then grabs the tow rope, which is looped around a tree at the river’s edge, and leans hard into the current. Skimming across the water, he beams up at the judge’s booth and his family and several hundred spectators. Then he lets go, dropping off into the top of Buseater and into a smooth, high-speed sequence of back- and front flips, spinning blunts and Pan-Ams, and a McNasty. All of the attendant drama of the past few days and years—his close calls and flushes, diligent strategizing, and obsession with branding victory—dissipates as he makes every move.

After E.J. has won his fourth world title, surprising everyone and no one, and Nick has finished third in his first world championships, and E.J. has taken his victory lap on Buseater—surfing it without a paddle—and Kristine has allowed herself one small breath of relief, the Jacksons regroup at the farmhouse. I’m expecting a blowout party (that will come later), but for now it’s family life as usual: folded laundry and video cameras on the dining-room table, footage to edit, and scores to report. Only E.J., sporting a skinny checkerboard tie, matching slip-on Vans, and a pleased, Peter Pan grin, looks truly relaxed. “I’m never nervous in the end,” he tells me. “If I made it that far, it means I got to play the whole way.”