Picture a heads-up display inside a helmet and you probably imagine something like the one from Iron Man. But most consumer products—snowboard goggles, Google Glass, etc—instead have a tiny micro display housed at the edge of your peripheral vision. It's less of an information overlay and more of an extra screen that you struggle to see. Its this disparity that Russian tech entrepreneur Andrew Artischev is trying to remedy with his new . We got to try an early prototype, and are excited to report that it genuinely made us feel like Tony Stark.

Artischev’s background is in apps, not optics. He was inspired to create a HUD motorcycle helmet after scouring bike shops in Moscow for what he was sure must exist, but that he couldn't find. He knew that giving motorcyclists easier access to information about navigation, speed, and the performance of their bikes made sense. He just needed to figure out how to pack all that data, plus a display, into a skid lid.

Why hasn’t there been an HUD motorcycle helmet yet? After all, the technology has been around in high-end cars from BMW, and even Chevrolet, for a decade or more. HUDs have been fitted in fighter pilots’ helmets for even longer. The answer lies in the complex series of jobs a motorcycle helmet has to perform—jobs no other helmet has to tackle.

Where a pilot’s helmet simply has to protect the wearer’s head from flying objects and serve as a mount for various auxiliary equipment, like an oxygen mask, radio, and visor, a motorcycle helmet has to provide adequate deceleration for the human brain in massive impacts—a racer walked away two years ago after —and small ones. (Concussions can occur during even waking-speed topples.) To achieve that, various densities of styrofoam are layered between the wearer’s head and the outer shell. Made from a strong but malleable material like carbon fiber or plastic, that shell deflects impacts and spreads their energy over a large area. are highly regulated, and those regulations vary between markets. The helmet you sell in Australia must meet different standards than a helmet sold in the U.S., for instance. Those regulations also cover the shape and size of the viewport, vents, and more.

One of the biggest considerations in motorcycle helmet design is in delivering good crash protection in a package with the smallest possible external dimensions. The smaller a helmet is, overall, the more aerodynamic it will be, and the lower the force with which it may twist a user’s head and neck. It'll also make the wearer look less like a Q-Tip. Heavier helmets also cause muscle fatigue and soreness.

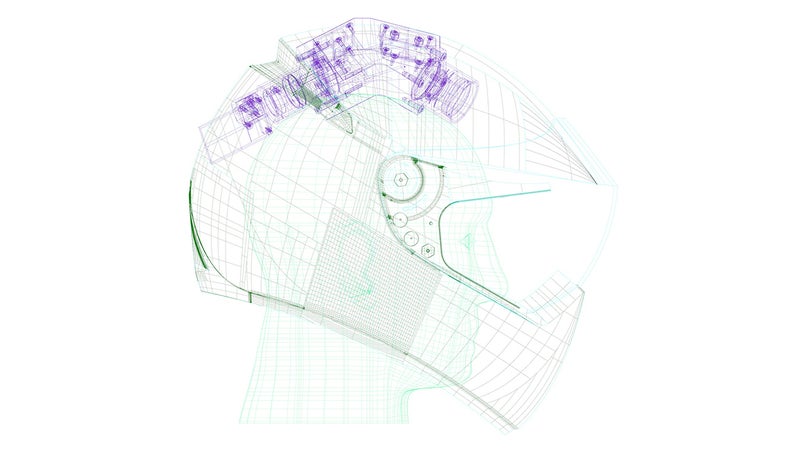

Therefore, just sticking a set of big optics and a computer in an existing motorcycle helmet is not an option. And that was Artischev’s challenge. So he basically set about reinventing the heads-up display, shrinking it, and adding unique, motorcycle-friendly functionality.

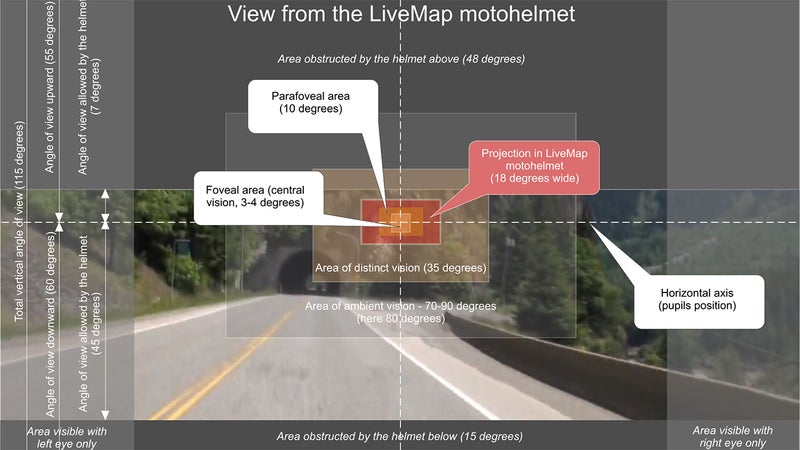

Unlike micro displays, which are basically what they sound like (little screens), a true heads-up display works by projecting an image onto a clear surface in front of your eyes. In so doing, it overlays data on vision, without the wearer having to change his focal point. Think about it: when you’re riding, are your eyes focused on a point one inch from your face or 100 yards away? By making the projected image appear as if it’s floating way out in front of you, you can see it without changing the focal distance of your eyes. A true heads-up display empowers users with data in an immediate way that isn't distracting.

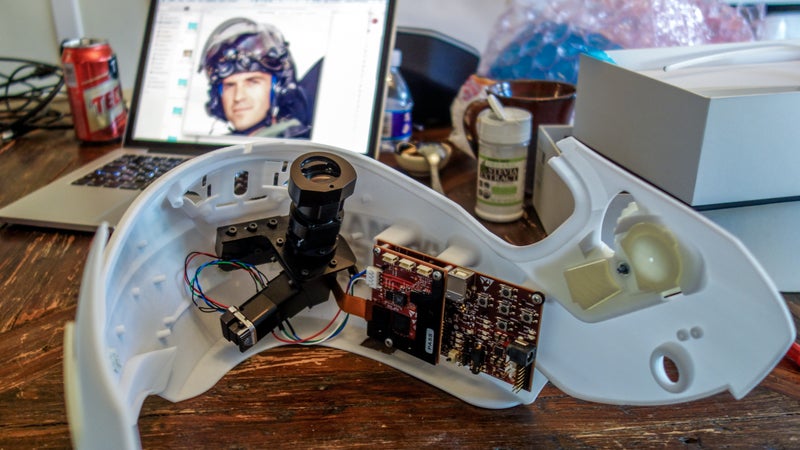

Artischev came over to my house in Los Angeles one day last week with the second generation prototype of his helmet. The optical projection system in it, and its processor, are much smaller than those used by fighter pilots or in cars, but remain larger than what he hopes to bring to production later this year. Wearing the prototype helmet, which still needs to be plugged into a laptop to function (so riding with it isn’t currently practical for review purposes), I was able to see a clear, bright image that covered a large part of my field of view. The projected image was bright enough to see, even while looking into Los Angeles’ bright blue sky, and it hovered out there at about 10 yards, allowing me to perceive its information without looking down at a tiny screen an inch from my face. Artischev says that focal distance will be programmable.

His company is called LiveMap for a reason. A big part of the need for this technology is to give motorcyclists heads-up navigation data. Particularly while riding in a city—a high-threat environment—bikers can’t afford the time it takes to look down at their speedometer, much less a busy navigation screen. By inserting data like speed, engine revs, and turn-by-turn navigation into your field of vision, Artischev hopes to empower better decision making while removing distractions.

Particularly in Russia, where insurance law heavily favors evidence, drivers and riders have started relying on “dash cams,” or constantly-recording, front-facing cameras installed in their vehicles that can provide an objective account of who’s at-fault in an accident. In a car, these dash cams can be bulky, but on a bike helmet, affixing even a GoPro can be awkward and uncomfortable. So Artischev is additionally including a front-facing HD camera in the helmet, and plans to include the latest cellular data connection to also allow live streaming from it. He’s achieving much of that, along with a tiny and low weight, by employing an off-the-shelf chipset from the Samsung Galaxy S6 smartphone. The LiveMap helmet will run on Android.

Artischev has developed the LiveMap helmet over a period of eight years, on a budget of just $1.5 million. Some of that was afforded by a grant from the Russian government, but most was derived by re-investing the profits from his previous business. He’s the kind of passionate inventor who truly believes his product is going to solve a real problem. After trying the system, I’m a believer, too.

Currently, I navigate on my bike in one of two ways. Around town, I typically look up directions, commit as much as I can to memory, pull over when that limited capacity is exhausted to consult my phone, then repeat. On longer trips, I’ll write shorthand directions on a piece of paper and duct tape that to my fuel tank. GPS navigators (or phone holders) that mount to your handlebars are available, but they're expensive, exposed to both theft and weather, suffer from poor UX design, and are difficult both to see and operate on the move. None of this is what you would call fool proof. The LiveMap helmet is.

One hurdle that Artischev isn’t trying to tackle—and this is smart—is in producing his own motorcycle helmet. Instead, he plans to purchase a white-label design that’s produced for several other non-HUD helmet manufacturers in Japan. Doing so means all the various legal hoops have already been jumped through, for every market, and that safety is already maximized. By employing a modular helmet—one where the face portion flips up (an arrangement preferred by cops and many other people who ride through cities around the world), he’s able to house the HUD optics and processor in the chin portion, which is not only less vulnerable to direct impacts in a crash, but is a largely empty, unused space. From there, the optics project an image up onto a proprietary visor, which reflects the image into your field of vision.

Without final production numbers, Artischev isn’t able to quote a finished weight for the helmet. But by using a high-end carbon fiber shell, he hopes to make it competitive with existing, low-tech, full-face designs. As for price, you obviously are talking about a significant premium for new and miniaturized technology, housed in a safe, high-quality package. He tells us to expect something in the region of $2,000 to $2,500. Helmets could be in the hands of consumers early next year.

That price puts the LiveMap helmet in the same ballpark as the Skully AR-1. That design, which has yet to come to market, falls well behind LiveMap’s true HUD solution. Instead, Skully is essentially housing a Google Glass-clone micro screen inside a similarly off-the-shelf helmet. —a world first—we found that solution to be neat, but the small display is obviously of limited utility and it's hard to see in direct sunlight.

If Artischev is able to deliver the LiveMap in 2017, and if he’s able to do so in a slick helmet which can be free of compromises, then I think he’s going to be genuinely onto something. This daily rider has his fingers crossed.