On July 2, Third Man Records (motto: Your Turntable’s Not Dead) successfully from Marsing, Idaho, into near-space. The Icarus craft ascended to approximately 18 miles above sea level—around ten miles higher than the typical commercial airliner flies—while playing a 12-inch golden disk of the late astronomer Carl Sagan’s “” on repeat. At its apex, the craft’s weather balloon popped and floated gracefully down to earth—still playing—before thudding into a vineyard at 22.5 miles per hour.

The first question—why?—is quickly answered: for a birthday. Third Man was turning seven years old later that month, and founder Jack White, of White Stripes fame, decided, “Why not?”

“Our main goal from inception to completion of this project was to inject imagination and inspiration into the daily discourse of music and vinyl lovers,” he , adding, “We hope that in meeting our goal we inspire others to dream big and start their own missions, whatever they may be.”

The next logical question, and the more important one for the device’s designers, is “how?” That question took scientists around the world more than three years of planning to answer.

A typical black PVC record would be turned into a blob of molten vinyl.

Kevin Carrico, a jack-of-all-trades repairman for Third Man in Detroit, Michigan, remembers the start of the idea. He and White watched a YouTube video in which a father and son in upstate New York launch a weather balloon with a camera attached. Carrico says it lit White up. “Jack’s first words were, ‘Why didn’t we think of this?’” Carrico says. “We realized that some of the same technologies we were using on the [record players] might actually help us during a flight.”

Several reasons made Carrico the perfect man for the job: he’s a former filmmaker, so he could document the feat. He lives in Detroit, near the auto industry, which inspired some of the craft's design. He has a rich family history in aeronautics. (Carrico’s father was a physicist on NASA’s Mars-Viking missions in the 1970s, one brother is an astrophysicist, and another works on flight analytics. His sister-in-law is a rocket scientist.)

The biggest challenge the Icarus craft would face wouldn’t be turbulence but lack of air. Going from a full atmosphere at launch to one percent atmosphere at its peak creates havoc in a semi-enclosed environment: a typical black PVC record would be turned into a blob of molten vinyl as soon as unfiltered solar rays began beating down on it. Then there was turbulence, sure. There was general movement, which would rotate the craft on three axes. Finally, there was a general x-factor. “We didn’t know what we’d find up there,” he says.

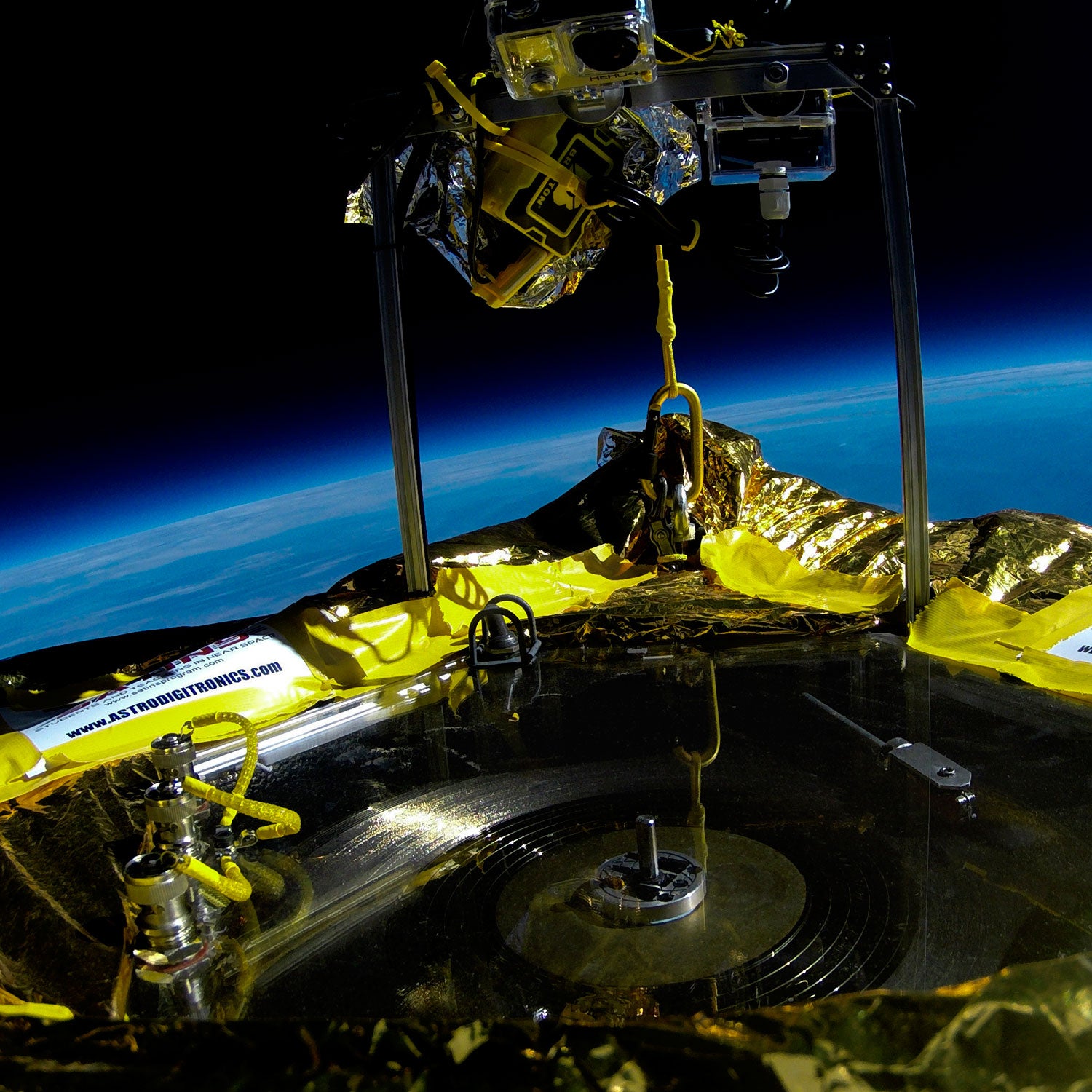

Carrico and his team engineered a variety of solutions for these problems to keep the craft and its cargo from melting and crashing into earth after a birthday surprise. The gold vinyl disk, chosen as an homage to Sagan’s famous gold-plated copper disks included on the Voyager spacecraft in 1977, actually turned out to be an unexpected boon—the exterior gold layer bounced solar rays. They also wrapped the craft with gold Mylar, similar to the blankets runners are given after a race, for the same purpose. The structure’s shape, a triangle of aluminum, proved to be the strongest, lightest, and smallest available.

The needle and phono cartridge were sourced from discontinued spare parts for Rock-Ola jukeboxes, while a Kevlar-reinforced drive belt kept the quarter-inch copper turntable platter spinning. The team selected , rated to minus 76 degrees, and Carrico custom-made brackets and a tone arm as final touches. All this was insulated with an inch of polyisocyanurate foam, commonly used for housing and designed in some sections like a car’s crumple zone.

To document, Carrico rigged up five GoPro Hero 4 Blacks, four outside and one inside, and powered them with five Brunton All Day 2.0 battery packs. He modified the camera cases to take in audio and prevent fogging.

For launch, he turned to David Jankowski, the founder and CEO of . Jankowski, an aeronautics industry vet, was in Spain at the time working for a commercial near-space tourism company when he got the call. “This payload was unique in a lot of ways,” he says, “but it worked.”

Using a standard 3,000-gram filled with 647 cubic feet of hydrogen, Jankowski added a , rated to 24 pounds. To track the craft upon landing, he installed two homemade radio-based tracking devices that could operate above 60,000 feet. “If one failed, it’s always nice to be able to find your stuff,” he explains.

The turntable, under Carrico’s expertise, was checked and rechecked. Finally, when a low-pressure system (read: calm winds) with clear skies popped up over Idaho, they jumped on a plane and headed west.

Around 8:40 a.m. on a Saturday, Icarus launched. It ascended for 81 minutes to 94,413 feet before its balloon burst, and then gracefully floated back to earth before landing upside down between rows of grape vines. All the while, the record played, the GoPros recorded, and Carrico, from the ground, waited for something to go wrong. Nothing ever did.

“We all just looked at each other, and no one really said anything,” Carrico says. “I know we did it, and I keep watching the footage, but it still hasn’t sunk in yet.”