Leaf peepers. European tourists. Motorheads from a nearby car show. On a Friday in September, maybe 100 visitors milled around Clingmans Dome, a popular lookout atop a high ridge in Tennessee's Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Some made the push to the ovoid, Jetsons-esque observation deck. The rest, exhausted by the half-mile approach from the parking lot, wiped their brows while standing on the flagstone patio below.

“Think it's OK if I fly this thing?” I asked a woman sitting nearby.

“This thing” was my drone. The size of a shoebox, with four outstretched arms and an HD video camera on its belly, the device is part of a new wave of even-dummies-can-fly-'em aerial robots, for sale to anyone with a couple hundred bucks in their pocket.

I wasn't sure what to make of it, honestly, but that wasn't the point. I was doing my first flight in front of other people, and the point was to see what they thought.

“You're not gonna fly it around for hours, are you?” the woman replied. I assured her that the flight would be short, 15 minutes tops. She seemed cool with that. Two park rangers, enthusiastic young guys in khaki shirts, had already told me to “Go for it!” while a third, an older woman in pressed green slacks, said, “You didn't hear that from me.”

That was all the encouragement I needed. I fired up the drone, which made an eager digital chirp, then four propellers the size of dinner knives spun to life and it obediently lifted off, climbing some 75 feet overhead. In the wispy fog blowing hard over the dome's 6,643-foot summit, the drone lurched forward and backward and side to side with all the predictability of a drunk. People on the ground stared. The folks in the lookout didn't even notice.

So I brought my drone closer in—right behind the young families, old men, couples, and kids in strollers gazing at the mountains in the other direct-ion. Finally, when they heard what sounded like a hive of angry bees, their heads swiveled.

No one appeared startled. No one cheered or threw rocks. Instead, they turned their bodies—away from Dolly Parton's homeland, away from the view that one woman later told me proved the existence of God—and, almost in unison, like primitives offering their humble devices to the higher technological power made plain before them, they raised their cameras, tablets, and phones. Once they finished photographing the drone, which was photographing them, they clapped.

Why, I can't say. The drone hadn't flown any loop-the-loops or thrown off glitter dust. But one thing was certain: these people were not afraid of a little old helicopter thingy.

No doubt about it, 2013 will go down as the year of the drone—the nonmilitary, for-sale-online, consumer drone. Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg discussed them during his weekly radio-show appearance. Chris Anderson, the former editor of Wired and cofounder of drone maker 3D Robotics, wrote multiple stories with titles like “How I Accidentally Kickstarted the Domestic Drone Boom.” New York University hosted its first drone conference. A computer-science undergrad in California launched a crowdfunding campaign, hoping to raise $10,000 to develop consumer drone kits that could be produced using 3-D printers; backers pledged $563,721.

In the outdoor world, camera-equipped flying robots were used to monitor the flow of sea ice in the Arctic, map an archaeological site in Peru, and chart forest fires in France and reefs in Samoa. A drone kept tabs on Kenya's endangered white rhino populations. Another mapped the Matter-horn down to 20-centimeter resolution. A pair of Louisiana hunters dubbed their drone the “dehogaflier” and used it to track wild pigs. A drone company helped map damage after last fall's floods in Colorado. Burning Man published a set of drone guidelines. (No buzzing the Great Circle until after the burn.) And hundreds of videos, distinguished by tags like FPV (first-person view), UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle), and quad-copter (four-rotor helicopter), were uploaded to You-Tube, with drone-enabled footage from Grand Canyon, Glacier, and many other U.S. national parks.

By last December, when 60 Minutes aired a piece about Amazon's plan to use drones for deliveries someday, a Domino's Pizza in London had already served up two large pies via drone, a bakery in Shanghai had couriered cakes using them, and Hobby King, a large online seller of all things remote controlled (RC), had kicked off its second annual competition to see who could lift the most beer into the air with a drone.

In the space of roughly three years, consumer drones have also become ubiquitous in photo and movie shoots. Virtually every state is home to at least one drone film company, including Idaho's RC Aerial Cam (customers: Discovery Channel, Red Bull, Salomon) and Tennessee's Snaproll, which flies drones of all shapes and sizes for clients ranging from General Electric to Taylor Swift. Photographer Corey Rich has used drones on some 30 adventure shoots. In a recent film for gear manufacturer Mammut, he deployed one to follow climbers David Lama and Peter Ortner to the 20,508-foot summit of Pakistan's Trango Tower. “They are game-changing devices,” Rich says. “They get our cameras in wild, unexpected positions, positions that are otherwise totally unachievable.”

Despite all this, drones remain a relatively uncommon sight at trailheads and atop mountains. But that could change fast. DJI, the maker of my drone and a leader in the afford-able, ready-to-fly market, rolled out the $500 Phantom in January 2013. The Chinese company declined to share numbers, but a dealer estimates that DJI will sell 100,000 drones this year. Parrot, a company that sells drones in Apple stores, has delivered more than half a million units since 2010. These figures are on top of the DIY kits and ready-to-fly drones sold by the thousands at online stores like Aerial Technology International, Quadrocopter, and Intelligent UAS.

The thought of all these little buggers flying around our favorite outdoor places is perturbing, as is the potential for harassment—of both humans and wildlife—and privacy violations. (Imagine how you'd feel if a drone whizzed by your head as you savored a successful climb of Mount Rainier.) But their appeal is just as apparent. When I first saw a popular YouTube video of surfing footage shot via drone at Santa Cruz's Steamer Lane, I swooned. It was so cool to have no idea where the camera would go next—right beside a rock with sea lions one moment, high above crashing waves the next.

The ability to capture cinematic footage is just part of the allure. A company called Hubsan makes a $200 palm-size drone that streams live footage to a screen on the controller—allowing, say, a backcountry skier to safely inspect a cornice before dropping in. 3D Robotics and others integrate an auto-tracking “follow me” function into their drones, enabling skiers and bikers, for example, to take the ultimate selfie.

The Federal Aviation Administration is struggling to keep up with these innovations. Last December, after Congress asked the agency to devise a plan for the “safe integration” of drones into national airspace, the FAA finally designated six sites for testing civilian versions of military drones. In the meantime, the only regulations that apply to recreational drone users are the ones that were implemented in 1981 for model airplanes, which forbid three major things: flying in crowded areas, flying above 400 feet, and flying near airports. As for wilder areas, the Forest Service and National Park Service neither encourage nor prohibit the launch of any object, though technically pilots are required to ask for permission before sending anything into the sky. “The business of unmanned aerial vehicles is real new to us,” says Jeffrey Olsen, a Park Service spokesman.

In other words, it's pretty much a drone free-for-all in America's wildlands. Or, as a TV producer who recently used an infrared-camera-equipped drone to look for Bigfoot told me: “It's about to get really freaky. There are already cameras everywhere. And now you've got these drones. People are gonna get pissed off. Others are gonna say, 'Screw you, I want to fly.'”

My newfound interest in consumer drones happened to coincide with a long-planned cross-country road trip. So I ordered a Phantom and charted a route that would let me fly it in beautiful wilderness areas between New York City, my home, and Seattle, where I was going to meet up with my family.

I figured it would be fun to capture footage of my trip, see how people react to some good-natured flybys, and explore whether a laissez-faire attitude about drones in the outdoors is the best approach. So, during the first week of September, I placed my new toy in the trunk of a rental car and set off.

I sped south for hours, skipping the barrier islands of Maryland to camp in the Cape Hatteras National Seashore of the Outer Banks—long, skinny sandbars in North Carolina that bracket the Eastern Seaboard.

Any fears I had about the skills required to fly a drone were quickly dispelled. While camped at Oregon Inlet, near the top of the cape, I learned by watching a couple of three-minute tutorials on my tablet. The next day, 45 miles south at Frisco Woods campground, I walked to an open area behind the dunes where local park rangers had cheerfully suggested I conduct my inaugural flight.

Some consumer drones fly autonomously, following tracks that you draw and create in an app; the Phantom is operated using a traditional radio controller. After installing the drone's battery, I completed the prelaunch dance of the controller sticks—left, right, apart, together—and the propellers began spinning. I nudged the left stick up and the drone ascended. I pressed the right stick to the right and it glided right. Then I thrust the left stick up and it rocketed into the clouds. Anytime I let go of the controls, the drone hovered in place. Amazing!

I made graceful arcs over sea oats, slalomed through oaks, and raced low, at about 25 miles per hour, along the yellow center stripe of a nearby tarmac, with the Top Gun soundtrack blasting in my head. It was a glorious 12 minutes. Then the battery ran low, and the drone dutifully landed itself back where it took off. Feeling the unique bond of man and tool, boy and spaceship, I immediately got on the phone and ordered more accessories.

A few days, two states, and a half-dozen flights later, I mustered the courage to fly my drone in public at Clingmans Dome. But it wasn't until later that night, when I stopped for pizza in the tourist trap of Gatlinburg, Tennessee, that I began to understand why some of the Clingmans visitors may have been less than stunned by my drone.

[quote]I made graceful arcs over sea oats, slalomed through oaks, and raced low, at about 25 miles per hour, along the yellow center stripe of a nearby tarmac, with the 'Top Gun' soundtrack blasting in my head. It was a glorious 12 minutes.[/quote]

While walking down one of Gatlinburg's main streets, I saw a storefront showcasing drones and RC helicopters—sandwiched between a fudge shop and Magnet-O-World. Astonished to find such techy toys amid the tourist stuff, and in need of some specialty batteries for my drone, I decided to pop in.

The store's proprietor, Kevin Lin, was a friendly guy in his thirties, with spiky hair and a pink polo shirt. He told me he moved to Gatlinburg from his hometown of Shanghai three years ago because he liked the weather. He noticed the rising popularity of RC devices and consumer drones, and he had friends back in China who worked in a factory that made them.

His little shop, King Hobby (not to be confused with Hobby King), now sells 65 models of RC helicopters and a handful of drones, and it has spawned no fewer than four competitors in town. “All the gun shops started carrying helicopters and drones, so now I have to carry guns,” he said with a smile.

I wasn't expecting this. There are almost

50 drone hobbyist groups in the U.S., but they tend to be concentrated in cities. I hadn't imagined that drones had made their way into the boiled-peanuts belt. But here they were. On Clingmans, I could've been a local.

The next day, I traversed the grand shelf of land that stretches from Knoxville to Nashville, Tennessee, descended to the Mississippi River, and pushed west to the Ozark–St. Francis National Forest in northern Arkansas, where I hoped to get some footage to wow my family and friends with.

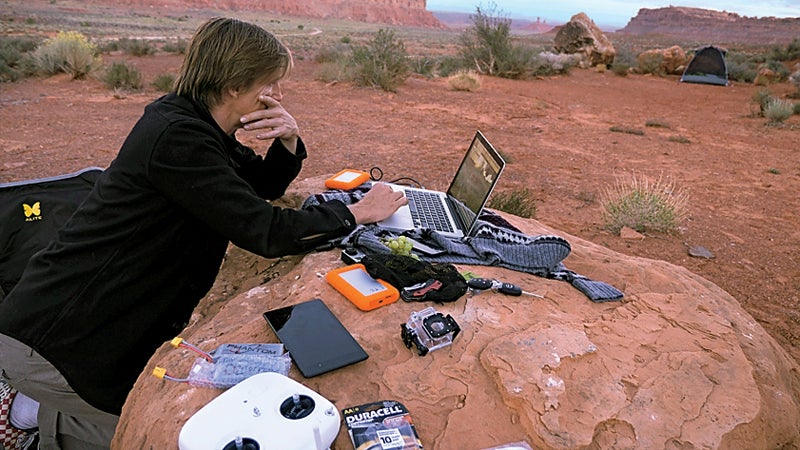

I filmed hiking trails and creeks and honey-hole lakes drenched in warm, humid air, but my most Planet Earth–worthy shots came at Buffalo National River, where I glided the Phantom along the smooth surface of the impossibly clear water and swooped up the face of a granite cliff at a gorgeous oxbow bend. The video, downloaded to my laptop, shows pebbles whisking across the screen, then a flat-gray wall, then—in a hallelujah moment—a wide-open, spinning vista of untouched oak forest.

I kept trying to get a rise out of people, but during two days in Arkansas, no one was intrigued or bothered by my flights. Granted, there were few around to care. The only other people I met in the backcountry, a couple with three young children, said nothing about my droning. The father wore an Army T-shirt, carried one of the children in a camouflage backpack, and had a bowie knife hanging from his belt and another strapped to his calf. The mother looked at me with apparent boredom. The other two children, maybe four and six years old, were too young for drone fascination. When I forced myself into their space to show them the Phantom, Mom changed the subject to a more relevant topic.

“There's a rattlesnake up there,” she said, pointing at the trail.

Not everyone is so blasé about the prospect of drones whirring around them. One vocal doubter is Phil Steel, a welding inspector in Deer Trail, Colorado, a decrepit ranching town 60 miles east of Denver, which I reached after a long, ponderous drive through the gridlands of Missouri and Kansas.

Deer Trail is normally a quiet place, but it became the center of a media circus last summer when Steel drafted a town-council initiative that proposed paying $100 to anyone who could produce the complete wreckage of a drone shot out of the sky. Never mind that gunning down private property is illegal. The drone ordinance will be voted on later this year, but it has already garnered all sorts of attention. Russian newspapers picked up the story. The Colbert Report mocked the idea. When I was in town, a crew from Univision, the Spanish-language cable network, was there, too, filming a segment.

As best I could gather during a one-day visit, residents remain split over the initiative.

The only person I talked to who clearly favored picking off drones was a lanky cook at a local diner. At breakfast I told the waitress about my drone, and she yelled back to the kitchen, “Hey! He's got a drone in his trunk!” The cook replied, “I don't wanna see it! He shouldn't be flying that around here!”

Invited out to elaborate, he said quietly, “I'd shoot it right outta the sky. I got guns.”

Residents opposed to the initiative aren't so much against shooting drones, I learned, as they are against almost anything Steel does. “He's just crazy,” said the owner of a gas station in town before telling me about the 22-foot lookout tower Steel built in his backyard.

When I finally met Steel at a fast-food restaurant, his greased-flat hair and monotone voice didn't do much to inspire confidence. Nor did his drone philosophy, which somehow sounded TED-like in a bad way. “Drones are where cyberspace meets real space and time,” he said.

But Steel could also be sincere, thoughtful, and funny. He planned to capitalize on his minor celebrity by launching a line of drone-hunter merchandise—clothing, ball caps, a cookbook. His proposed ordinance was mostly a stunt, but his worries about the future pervasiveness of domestic drones seemed legitimate enough.

“If a pedophile was using a drone to take pictures of kids today, someone would see it and it could be stopped,” he said. “But when they're ubiquitous, how do you tell a good drone from a bad drone?”

Later, I had a phone conversation about drone pitfalls with Woodrow Hartzog, a privacy lawyer and affiliate scholar at Stanford University's Center for Internet and Society. The time to ask questions about drones and privacy, he said, is now.

“Once a technology is adopted by the masses, it becomes much harder to regulate,” Hartzog explained. As an example, he cited online tracking software like site cookies, which remains largely ungoverned. By the time groups that wanted a sharper definition of privacy got organized, the technology had already spawned thriving industries with powerful corporate support.

I got the sense that, despite the hoopla, even the anti-droners in little Deer Trail hadn't really begun to organize. But it was time to find out. At 1 P.M., on the street just behind the town hall, I sent my awesome and vexing little drone into the sky. From 150 feet up, I peered into backyards, surveyed double-wide trailers, and filmed an auto repairman's car-strewn property, which locals call the Asshole's Garage.

Nobody shot my drone out of the sky. A white-haired couple in an Oldsmobile drove underneath it unaware, as did a farmer on a tractor. Steel, I knew, was off inspecting pipelines in another town. And I got the feeling that anyone else who might have taken aim was also out trying to earn a living.

I crossed the Continental Divide and headed into the smooth orange landscape of southeastern Utah, arriving in Canyonlands National Park 20 minutes before sunset.

The recent delivery of additional batteries and propellers had created a technological jumble in my car. Along with all the computer screens and mobile devices, I now had more stuff that needed charging, that bounced around in cup holders and hid in the bottom of bags and cases.

I desperately wanted to launch my drone off the 6,259-foot-tall mesa that overlooks the Needles District before dark, but it took me several minutes to find the damn screws to attach my GoPro camera. And in the prelaunch frenzy, I didn't pause to create the usual flight plan or scope out a landing area. Instead, while a lone German stared peacefully at the western set piece, I made a hasty launch. Then: streaks of light, frantic motion, a high-frequency buzzing. With the battery nearly empty, I tried to steer my craft for an emergency landing in a gully, but I failed. The drone banged into a rock and hopped around in the dirt until its propellers, scuffed but not broken, whacked themselves into exhaustion.

I'd known this day was coming. A plethora of news stories and YouTube videos featuring the word “crash” had hinted at it all along.

Over the course of my trip, a drone crashed in a crowded street in Spain. Three days later, in Germany, a drone nose-dived at the feet of Chancellor Angela Merkel. Two weeks after that, in Manhattan, an idiotic New Yorker in ripped jeans launched a Phantom from the balcony of a midtown apartment building. Soon it pinged into the side of a skyscraper. The drone miraculously righted itself, but the pilot sent it beelining into another building. And another. Eventually, the thing tumbled some 30 stories, smashing on the sidewalk near Grand Central at the start of rush hour, steps away from a startled businessman.

The FAA is working to prevent such crashes, of course. Meanwhile, individual states are largely responsible for trying to figure out how to weigh a person's right to privacy against a person's right to use drones and cameras in public places. As the handful of states with drone-specific regulations have discovered, this is not an easy balance to achieve.

Take Texas. In September 2013, state legislators outlawed drone photography of a private entity without consent. Some celebrated the law, which prohibits, for example, private detectives from using drones to snoop around bedroom windows. But others decried the way it handcuffs people seeking to do good for the public, like the hobbyist drone pilot from Dallas who captured footage of a meatpacking plant that had been dumping untreated waste into a nearby river. If the law had been in place when he'd photographed the fouled waterway in January 2012, he wouldn't have been able to use the images to help indict the plant owners on pollution charges.

Questions about drones in federal wilderness are even more complicated. Not only are there safety, privacy, and First Amendment concerns, but there are questions about how drones jibe with the authorized use of these lands, which includes preserving solitude for visitors and protecting wildlife from unnecessary harassment.

Unfortunately, none of the federal agencies appear poised to answer these questions. “Once any kind of vehicle takes off from a national park and goes into the air, that's national airspace,” says Park Service spokesman Jeffrey Olsen. Adds spokesman Lawrence Chambers, “The FAA has regulatory authority over all airspace. The Forest Service doesn't have any additional regulations regarding where they can or can't be flown.”

FAA spokesperson Alison Duquette acknowledges the administration's's responsibility for drone safety but says that other concerns—such as calls for drone-free tent sites—fall outside the FAA's purview. “Hobbyists have to stick to the hobbyist rules, like staying under 400 feet,” she says. “I don't know if the Department of the Interior has any special regulations about parks.”

This is troubling. If the history of wildland airspace is any indication, drones in growing numbers will continue to invade wilderness areas while federal agencies are busy passing the regulatory buck.

That's largely what happened with passenger flights over national parks. The number of noisy scenic helicopter tours, Air Force training flights, and private-craft flyovers grew rapidly during the seventies and eighties, with the Park Service eventually concluding that overflights led to unacceptable noise-pollution levels in a quarter of the parks. Visitors complained. Arizona congressman John McCain was astounded to see a plane flying below him, thousands of feet under the rim of the Grand Canyon, while hiking in the early eighties. Then two sightseeing aircraft

collided over the Grand Canyon in 1986.

In 1987, McCain introduced and Congress passed the National Park Overflights Act, which mandated that the Department of the Interior, which oversees the Park Service, collaborate with the FAA to produce “the substantial restoration of natural quiet” inside parks. The act ordered the two agencies to produce new regulations within a year, but the first ones didn't start arriving until 2002. As a frustrated McCain, by then a senator, said in a committee hearing that year, “In 1987, I never believed 15 years later we would be sitting here still without this issue having been resolved.”

Whether regulating drones requires an act of Congress is uncertain. A special addition to park bylaws, like the ban on Segways that some parks decreed in the mid-2000s, could be allowed on a case-by-case basis. Meanwhile, environmental groups aren't pushing to find out. The strongest stance I could find came from the Wilderness Society, and it's pretty weak. Said the organization's Jeremy Garncarz: “We know this may be something we have to address in the near future.”

On a Tuesday in late September, I skittered into Portland, Oregon, just in time for a dinner meet-up of two dozen consumer-drone enthusiasts at the hip Ace Hotel. The crowd included members of a drone consultancy, the founders of a booming drone retailer, an angel investor, and the president of a drone trade association.

Before I could stab a fork into my mushroom farfalle, attendees were overwhelming me with all the now familiar ways that drones are doing work that is “dull, dirty, or dangerous.” They were an impressive, well-

intentioned lot. Heck, one guy was headed to Greenland the following day, where he would use drones to count the dwindling polar bear population. But they were squarely focused on the amazing things they could do with drones, not on what drones might do to us—which had increasingly become my concern.

During my three-week road trip, the price of a Phantom dropped $200 and DJI debuted a new model that's able to fly twice as long. Just eight months after the Phantom's release, a fellow camper on North Carolina's Outer Banks told me he saw one flying over his tent, and the German at the Canyonlands overlook saw a Phantom flying around Delicate Arch the morning before I met him. It doesn't take much of an imaginative leap to picture a drone bouncing off the arch, or a handful of drones swarming climbers on Yosemite's El Capitan or dive-bombing a herd of bison in Yellowstone.

The following day, I escaped to peaceful Camp Westwind, a 529-acre conservation area and wilderness-education center on the Oregon coast. I'd arranged to meet Jonathan Evans, the bright and friendly founder of Portland-based drone-consultancy and software-development outfit RTI, who was there to pitch Matt Taylor, the camp's executive director, on how drones could help him monitor the spread of invasive plants.

The three of us canoed across the bird-flocked estuary of the Salmon River and ascended a forest path to the main lodge, where we met two pilots hired by RTI. Down at the shoreline, they launched a drone with a secondary camera that beamed an eye-in-the-sky view back to a pair of goggles worn by one of the pilots. The pilots took pains to avoid buzzing the grade-school campers learning about trees and instead focused on the border between beach and forest, where a nonnative shrub had been spreading.

Taylor was skeptical but curious. Then he donned the goggles, which allowed him to see what the drone was seeing. “Whoa!” he said. “This could be an amazing tool.”

RTI's plant survey is just a demonstration. In addition to its other restrictions, the FAA forbids companies like RTI from collecting money for commercial drone services. That will change sometime later this year, when the FAA says that it will begin allowing pilots of consumer drones (whom the administration refers to as “hobbyists”) to set up shop.

It could change even sooner. Following a $30 million investment in Chris Anderson's 3D Robotics last December, members of DIY Drones, an online community Anderson started, circulated a White House petition to allow consumer operators to immediately use their drones for profit. It didn't get the signatures, but setbacks like that don't deter guys like RTI's Evans. “We're putting together a business plan and making connections for when the regulations open up,” he told me.

A few days later, I returned the rental car in Seattle, hugged my family, and continued to fly my drone, teaching my father how to move it low and fast while my mother stood by saying that it's “creepy.” Soon after, I called Taylor, who had become even more excited about the prospect of drones at Camp Westwind.

“If the drone were equipped with monitors that helped us tease out signatures for different species, and it was affordable enough that we could do monthly or quarterly flyovers,” he said, “then we might be able to do some really smart prioritizing about eliminating invasives.”

That said, the future troubles him. “When you go to Yosemite's Hetch Hetchy Valley, like I did back in '92, and a hummingbird flies up into your face, two inches away, and you can feel the beats of its wings—that's cool!” he said. “I don't want a drone to do that.”

Indeed. The thought of more drones, controlled by guys like me at precious places like that, is distressing. It will sound radical, but this is what I've come to believe: We should ban the use of drones in all federal wilderness areas immediately.

���ϳԹ��� contributing editor wrote about Japan's Niseko Ski Resort in January