Is Your Local Chairlift a Death Trap?

Our nation's lifts are at the breaking point. We spent months researching past accidents and aging infrastructure—and found that it's time to act in order to avoid catastrophic failure.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Timothy Yates woke up on Saturday, February 20, prepared for victory. The 45-year-old tech CEO from Williamsburg, Virginia, had some of the top slalom times in his region, but fate had repeatedly robbed him of the Southern Alpine Racing Association’s championship masters title. Last season, he was disqualified for missing a gate. This year, the competition was taking place at the Timberline Four Seasons, a family-run resort in West Virginia. Yates had tuned his race skis, honing them with four different stones until they were as sharp as samurai swords. “I’m going to win this one,” he thought.

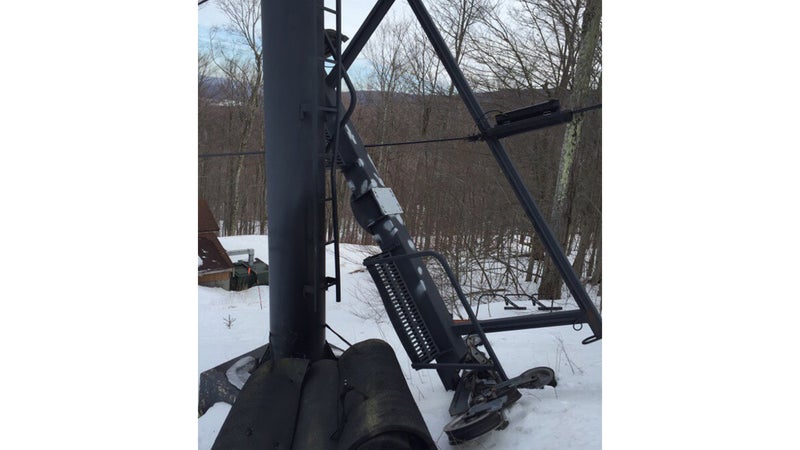

At 8:30 a.m. EST, Yates hopped on the Thunderstruck lift for a course inspection. Thunderstruck rises 1,000 vertical feet to the 4,268-foot summit of Herz Mountain, named after the family of Timberline owner Fred Herz. It’s an old three-seater that was installed in 1985 by Borvig, a New York–based company that went out of business eight years later. The chairs hang fixed to a metal haul rope running between a series of black towers. Atop each tower sit the crossarms that support a train of grooved discs—or sheave wheels—that rumble whenever a chair hanger rolls over them. That day, as Yates approached Tower 12, he gazed in disbelief as the crossarm tipped away from him in slow motion. The haul rope slipped free from the wheels, and his chair plummeted toward the ground 30 feet below.

Yates doesn’t remember what happened next, but witnesses saw the chair recoil on the rope after the initial freefall, like a rubber band pulled taut, and released, slingshotting him and his two fellow passengers 25 feet into the air. He left a foot-deep impression when he face-planted into the soft snow. As Yates marveled that he was conscious and still alive, his chair whipped a few feet overhead before smashing to pieces against the tower. His pain came later, once the shock wore off. He skied down with the help of ski patrol and an ambulance took him and his daughter to the hospital. He would later learn that he had three broken ribs and elevated liver enzymes, suggesting organ damage.

Yates wasn't the only skier injured that day. Approximately 25 people fell from Thunderstruck, including Yates’s then 17-year-old daughter. More than a hundred other riders had to be evacuated over two tense hours as the towers groaned. The championship was postponed for a week and relocated to another resort. Yates’s doctor made him skip it. Today, his right elbow hurts so badly that he can’t pound more than one nail into wood at a time. “I may be able to ski with a bum arm like that, but I won’t have a good start,” he says. His friends at his home resort of Wintergreen gave him a trophy at the end of the season to make up for the bad luck: Men’s Aerial, First Place.��

Mechanical lift failures remain exceedingly rare in the United States, but when they do happen, they raise troubling questions about how well many of the country’s approximately 3,000 lifts, gondolas, and trams are maintained. And some experts fear that failures will become more common as the country’s ski infrastructure continues to age. Just days after the West Virginia accident, Vermont officials shut down a 40-year-old Borvig lift at Suicide Six Ski Area after ��in two towers where the crossarm meets the tower head. According to ,��176 Borvig lifts remain in operation in 26 U.S. states and three Canadian provinces. Another lift manufacturer,��Doppelmayr, recently issued warnings about cracking in towers installed in the mid-1990s: British Columbia’s Big White Ski Resort had to on its Doppelmayr lift.

For decades, ski resorts have resisted calls for greater governmental oversight, arguing that their voluntary standards and self-inspections are rigorous enough. According to statistics compiled by the National Ski Areas Association, a passenger is five times more likely to die riding in an elevator than on a ski lift and eight times more likely to die in a car. “We haven’t had a fatality from a lift malfunction in 23 years,” says David Byrd, the association’s director of risk management. “I think that’s a pretty remarkable safety record.”

But in an era where ski resorts are often as starved for cash as they are for snow, maintenance standards and equipment quality vary. Most lift-related injuries have occurred at smaller resorts with skimpier budgets, some of which have lifts in operation dating to the Eisenhower presidency. Five years ago, a chair with two teenagers fell from a .

In industry presentations, Gary Mayo, a customer support manager for Doppelmayr USA in Salt Lake City, has compared the nation’s aging lifts to the iceberg that struck the Titanic: on a bluebird day, you sit back on your lift and look around, and all you see are the majestic snow-covered mountaintops. But beneath your seat is a clunky machine patched together from components that could be housed in the Smithsonian. “The earliest detachable lift installations in the United States have already surpassed the initial targeted life expectancy!” reads a summary of Mayo’s talk about planning for aging lifts from the . “What is lurking out there to sink YOUR ship?”

Since 1996, the average age of our nation’s lifts and gondolas has risen from 17 to 27 years old, according to a database compiled by��, founder of Lift Blog. Today, approximately two-thirds are more than 20 years old, and half of those are older than 35. Almost 100 lifts in operation were first installed more than 50 years ago, including Mad River Glen’s��, which was installed in 1948 and has been extensively refurbished. The NSAA and manufacturers��decline to put a number on the lifespan of a lift. “The analogy we like to use,” says Byrd, “is that they are like an old car: if they are maintained and you have parts that are replaced, they can run for decades.”

But keeping that 1971 Mercury Comet running reliably isn’t a straightforward proposition, particularly as off-the-shelf parts become unavailable and seasoned mechanics retire. “If it runs good, you don’t think about it,” says Jim Vander Spoel, who runs a lift maintenance program at Gogebic Community College in Ironwood, Michigan, and manages operations for the Porcupine Mountains Ski Area. He teaches his students how to diagnose and solve acute mechanical issues, but it’s harder to spot problems like metal fatigue and wear that develop after decades of use. “There haven’t been many failures yet,” he says. “It’s coming.”

There are also myriad variables to consider when assessing the health of an aging lift. A lift in a mild climate may last longer than one that gets encrusted in ice every winter, and a part-time lift on the back of a mountain will see less wear than the workhorse on the front, according to slides from Mayo's Doppemayer presentation. But by the time a lift gets to be about 25 to 30 years old, the cost of replacing all the fatiguing components, including the chairs and grips, could be 85 to 90 percent of the cost of installing a modern lift. “It makes more sense to buy a new one,” says Jim Fletcher, a ropeway engineer with��consulting firm SCJ Alliance.��

The chair recoiled on the rope, like a rubber band pulled taut, and then released, slingshotting passengers high into the air. Yates left a foot-deep impression when he face-planted into the snow.

That’s an investment many small ski areas may not be able to afford. “The maintenance guys in the field are saying, ‘We need to do this,’ and the boss is saying, ‘How much does it cost?’” says Porcupine’s Jim Vander Spoel. Thirty years ago, it may have cost $200,000 to install a new lift. It costs around $1.5 million today. “A lot of these smaller operations would be out of business if they had to replace this stuff,” he says.

One of the worst chairlift��accidents in recent history underscores the challenges of maintaining older lifts. On December 28, 2010, Michael Katz, a 48-year-old anesthesiologist and Delaware state senator, loaded the Spillway East lift at Sugarloaf Resort with his two daughters. As the 1975 Borvig double began the ascent, Katz heard a humming noise, then the lift abruptly stopped. The humming was the sound of the metal haul rope coming off a sheave wheel on Tower 8 and rubbing against a flange designed to limit the rope’s movement.

Noah Lake, a maintenance man in his 20s, climbed up the tower to fix it. After Lake tightened a metal turnbuckle that pressed against the wheels, he radioed the operator to restart the lift. Katz’s chair lurched forward, but the rope still was not seated in the grooves, and the lift stopped again. Thirty-five feet above the ground, Katz’s chair swayed. Before trying a new repair strategy, the lift operator decided to run the lift at slow speed to unload skiers.

Five seconds later, Katz felt a jolt, and then everything went black. The rope had fallen from the tower, bringing five chairs down with it. “I remember gaining consciousness on the ground, and there were people working on me,” Katz says. In addition to a head injury, he broke his back and several ribs, and sustained a torn spinous ligament and collapsed lung, which filled his chest cavity with blood. The accident resulted in four other serious injuries. Katz’s older daughter, Abigail, had a lumbar compression fracture, and both daughters sustained concussions that were serious enough to prevent them from returning to school for three months. Today, Abigail, 18, has a herniated disk that will require surgery.

An from Maine’s Board of Elevator and Tramway Safety called the resort’s maintenance records “inadequate” and found no evidence that it had removed and checked the sheaves every four years as recommended by some Borvig manuals.

Sugarloaf had modified the original sheave assemblies, adding turnbuckles to stiffen them in the wind. But the stiffeners weren’t designed to be adjusted with a loaded lift, and the older workers who knew that fact had all retired. When the lift was restarted that day, the force snapped the turnbuckle, catapulting the haul rope onto a cable catcher. Because the resort lacked an automatic shutoff switch on the uphill side of that tower, the lift continued to run, and the rope slipped from the catcher.

Katz’s family sued Sugarloaf, eventually settling for undisclosed terms. “We didn’t ski for two years,” says Katz, who owns a home on the mountain. “We slowly got back into it, but we still have a lot of fears about being on lifts.” His worries weren’t unfounded. On March 21, 2015, several chairs on Sugarloaf’s King Pine lift—a Borvig lift installed in 1988—, stopping only when the lift operator activated the emergency brake. Seven skiers received minor injuries.

In , John Burpee, Maine’s chief lift inspector, surmised that a “gear appears to have failed some time before the March incident but went unnoticed.” This maintenance oversight caused the gearbox to disengage and an automatic brake to fail. Burpee also suggested that ski areas consider upgrades to make their lifts safer. “Older lift systems may not be as reliable as new systems designed to fulfill the same function,” he wrote. Sugarloaf says it has tightened its operations and invested $1.5 million in upgrading older lifts over the past year. “It’s not the way you want to learn lessons about your lift maintenance program,” says Sugarloaf spokesperson Ethan Austin.

“Skiing is an inherently dangerous sport,” reads the boilerplate on a typical lift ticket. Indeed, being a skier means accepting a long list of risks, but of the tens of thousands of emergency room visits and dozens of deaths that occur at ski resorts each year, most happen when one skier collides with another or takes a tumble on dangerous terrain.

Chairlift accidents happen, too, but the greatest dangers on lifts come from inexperienced skiers slipping during loading, or children and distracted riders falling to the ground. In December 2014, a woman caught her ski on a support pole at Hunter Mountain in New York and . Colorado is one of the few states that require resorts to report injuries resulting from lift falls. In the past five years, 74 people were injured falling from lifts in that state, according to numbers provided to ���ϳԹ��� by the . The agency classified three of those as the lift operator’s fault.

Lift malfunctions that result in fatalities are extremely rare. In its 2014 , the NSAA lists 12 deaths and 73 injuries resulting from 10 lift malfunctions in the United States since 1973. (Over that same time frame, there have been at least 102 fatalities at European resorts from lift malfunctions—nine times the fatality rate at U.S. ski areas.) The last time someone died in the United States following a malfunction was in 1993, when a sheave wheel fell off a tower on the Slingshot, a at the Sierra Ski Ranch (now Sierra-at-Tahoe). The malfunction caused an empty chair to get hung up. When the next chair, carrying a nine-year-old British boy named Michael Roper, slammed into the empty one, Roper was flung from the lift, and he died from head trauma.

“As long as customers aren’t aware of the problem and don’t know that things aren’t as good as they look, there’s no pressure on resorts.”

But here’s the rub: because there is no national requirement to report injuries, the NSAA’s numbers are not comprehensive. Only after ���ϳԹ��� began asking questions did the NSAA update its fact sheet to , Philip Giles. He also fell from the lift and was hospitalized in “serious but stable condition” from “facial injuries and a bruised liver,” according to the San Jose Mercury News.��

For the most part, ski resorts regulate themselves. The NSAA is the secretariat for the committee that maintains , a standard for the design, maintenance, and inspection of ski lifts and trams. The standard was developed in July 1956, shortly after a corroded chairlift cable at New Hampshire’s Gunstock Mountain snapped, killing one and injuring seven others. The tragedy was a wake-up call at a time when ski areas were rapidly expanding and lifts were being . The standard has been updated sporadically since its inception, according to Byrd, and specifies maintenance protocols, such as monthly brake tests and annual lift inspections by an outside engineer—albeit one paid by the resort.

But only some states'��agencies have adopted parts of the standard in their regulations, and it’s enforced by even fewer. Colorado and Vermont, home to 18 percent of the nation's lifts, are that have tramway safety boards who either have full-time staff members or hire contractors to conduct annual inspections, but they are largely spot checks. “My inspectors don’t climb every single tower,” says Stephen Monahan, head of Vermont’s .“Ski area maintenance people are supposed to do that.”

Ski areas in the other 11 states with tramway safety boards are only required to hire a certified inspector to sign off on their lifts. West Virginia, which has 27 lifts, doesn’t even have that level of regulation. And the ANSI B77 is not legally binding. Idaho, Oregon, New Mexico, Minnesota, Montana, and Wyoming also lack state safety boards, although those that operate on U.S. Forest Service land may receive a cursory check from a recreation ranger. (The Forest Service banned detachable Yan lifts in 1996, following a deadly accident at Whistler in Canada.)

Often, the only independent inspections are conducted by the ski area’s insurer, but these checks are about as in-depth as your annual car inspection. “The insurance company has their own set of goals, and it’s not necessarily the same as a public agency,” says Benjamin Gideon, a personal injury lawyer at Berman & Simmons in Lewiston, Maine, who represented Katz and other clients with claims against Sugarloaf. Their ultimate goal is to ensure that the premiums they receive outweigh the payouts. “Remember ?” he says. “Ford made the decision that it was more cost-effective to pay clients than to fix the problem.”

The NSAA says it supports efforts to make the ANSI B77 code standard for states and that the insurance inspections are only one part of a broader process of maintenance and oversight.

In the days following the accident at Timberline, Tim Yates learned firsthand about the flaws in the regulatory system. He read a about a service bulletin that Borvig’s president, Gary Schulz, sent out in 1987 . “In the course of last year’s winter operation two ski areas had discovered weld cracks in the tower cap located below the crossarm,” Schulz wrote. The company would pay for the installation of U-bolts to reinforce the crossarms before the next operating season. “We feel that it is essential for a safe operation.”

When Yates looked at his photos of Thunderstruck, he didn’t see the U-bolts, and he became fixated on digging up more information. He polled two resorts with similar lifts and found they had both completed the retrofit at the time. According to Gary Schulz’s son Hagen, who is the president of Partek Enterprises Inc., which services��Borvig��lifts, his company��coordinated repairs to add the missing U-bolts the week following the accident at Timberline. “No one ever verified that the modification was done, and 28 years later, lo and behold, the failure surfaced,” he says. “The maintenance people that work there are good people, but do I think they have the resources to do their job properly? The answer is no. That is a problem throughout the industry.”����

, Timberline says the tower failed due to a “hidden defect” and that the resort “adheres to every precautionary and professional standard in the industry.” The resort did not respond to specific questions related to the U-bolts. “For us and our public, it’s no longer a story, and we are moving on,” says Tracy Edmonds Herz, vice president of Timberline.

In response to questions about lift safety, the industry often maintains a circle-the-wagons mentality. On the morning of May 3, David Byrd gave the keynote talk at the conference with a bullet point reminding ski area employees never to talk to the media. “The miscues in our lift operations and maintenance are magnified and sensationalized beyond their true impact, but the damage to our industry and the sport is often disproportionate to the actual incident,” Byrd warned in his abstract, noting that “the media’s initial reaction only leads to eventual legal and regulatory headaches.”

Byrd also alerted them to this article, which he suggested was going to be hard on the industry. One lift operator told ���ϳԹ��� that he came away from the the talk fearing that he would lose his job and never be able to work at a ski area again if he was named in this report. Others have also been wary about sharing information with the media. While Gary Mayo initially provided ���ϳԹ��� with a copy of Doppelmayr’s aging lifts presentation, he later wrote that the information contained within it was “proprietary” and “may not be used in any way,” referring further questions to the NSAA or to Doppelmayr’s president.

Byrd declined to comment on the failings of individual resorts, but the NSAA frequently . “There’s an atmosphere in the industry of us versus them,” says Dick Penniman, the chief research officer at the , who has worked as an expert witness for injured skiers for more than 30 years. Penniman says he was kicked out of the NSAA's 1986 annual convention at Disneyland Convention Center for talking about ski safety regulations. “As long as customers aren’t aware of the problem and don’t know that things aren’t as good as they look, there’s no pressure on them,” he says. The NSAA says that no group would allow someone who testified against it to attend its meetings. “It is estimated that he has been paid well over $1 million (if not twice that) by plaintiffs and their lawyers for offering uninformed opinions in litigation,” Byrd wrote ���ϳԹ��� in an email. “It is laughable how little actual experience and understanding he has of ski area operations.”

While dedicated skiers may sneer at the SnowSport Safety Foundation’s , which rates features like signage and padding on poles, Penniman says it’s not trying to turn Kirkwood into Disneyland but instead wants consumers to be able to make informed decisions. The foundation helped craft the California Ski Safety Bill, which would require ski resorts to post a safety plan and report serious injuries and deaths. The state legislature passed the bill in 2012, but then��Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed it, arguing it would place an “.” In 2013, Governor��Jerry Brown vetoed a similar bill.

If the industry has been allergic to some forms of regulation, Jim Vander Spoel says that attitude is not coming from lift mechanics. “I always look forward to having another set of eyes on my work,” he says. Vander Spoel sits on the ANSI B77 committee, which is preparing to publish a new standard, likely in 2017, and he suggests that skiers in every state encourage their legislators to make it legally binding. “I would like to see this adopted nationwide,” he says.

Others say the industry could go further, following the practice in France and the Canadian province of Ontario, where lifts must receive an in-depth mechanical evaluation after 15 or 20 years in service to bring them up to current standards. Hagen Schulz, of Partek, would like to see a mandate that parts be checked for wear and replaced at regular intervals, as is required with aircraft. “There’s been a lot of talk about it, and the pushback comes from the resorts,” he says. The NSAA points out that the ANSI B77 standard already requires that ski areas adhere to manufacturers’ recommendations and that they are free to include such schedules in their manuals.

For now, without consistent regulations, skiers must decide whether they can��continue trusting the lifts at the local ski hills they know and love. The clock is ticking for many small ski areas and the message is clear: upgrade or bust. “That’s the lifeblood of our industry,” Vander Spoel says. “I’d hate to see all these small guys disappear.”