To those outside the snowsports world, the news on October 4 barely registered. K2 Sports, one of the��most storied brands in U.S.��skiing, was��up for sale. Again. Just a year before,��its behemoth parent company, Jarden, was absorbed by an even bigger behemoth, Newell Brands, in a $15 billion deal. Now��the ski industry’s heritage manufacturer stared down an uncertain future.

Except this time the circumstances sounded more dire. Not only had Newell put K2 up for sale, it had done the same with the rest of its snowsports portfolio, which includes smaller, cult-classic brands like Line skis, Full Tilt boots, and Ride snowboards, as well as big��guns like��, , and . Newell was trying to cut its lesser-performing “distraction” brands, as CEO Michael Polk put it, and focus on the bigger companies in its portfolio, which includes Rubbermaid and Sharpie. It's not surprising, in a four-quarter market,��that many of these��were companies��that rely on diminishing snowfall to sell one-season products.��(According to K2,��the��brands��being��listed��for sale was “unrelated to the performance of the businesses,” K2's��Sports Vice President of Marketing Alex Draper��explains. “Our brands, products, and retailers do not cross over with [Newell's] core businesses and core customers and are therefore not a fit for their business model.”)����

The firestorm also came with a caveat��from Polk: if any of the brands didn’t sell, they could be shuttered for good.��

To those inside the snowsports world, the prospect of that happening—and the industry’s sudden��vulnerability—was shocking.��“It really freaks me out,” says Nick Sargent, president of the trade association SnowSports Industries America. “There are some smaller brands in Newell’s portfolio that I could see someone shutting down, but when you look at the revenue that those bigger brands contribute to the industry, it’s really hard to think of those just being walked away from. It would damage our industry in a significant way.” According to��SIA, K2 and��Volkl��control 32 percent of the alpine-ski��market in the U.S., which last year totaled $260 million.��

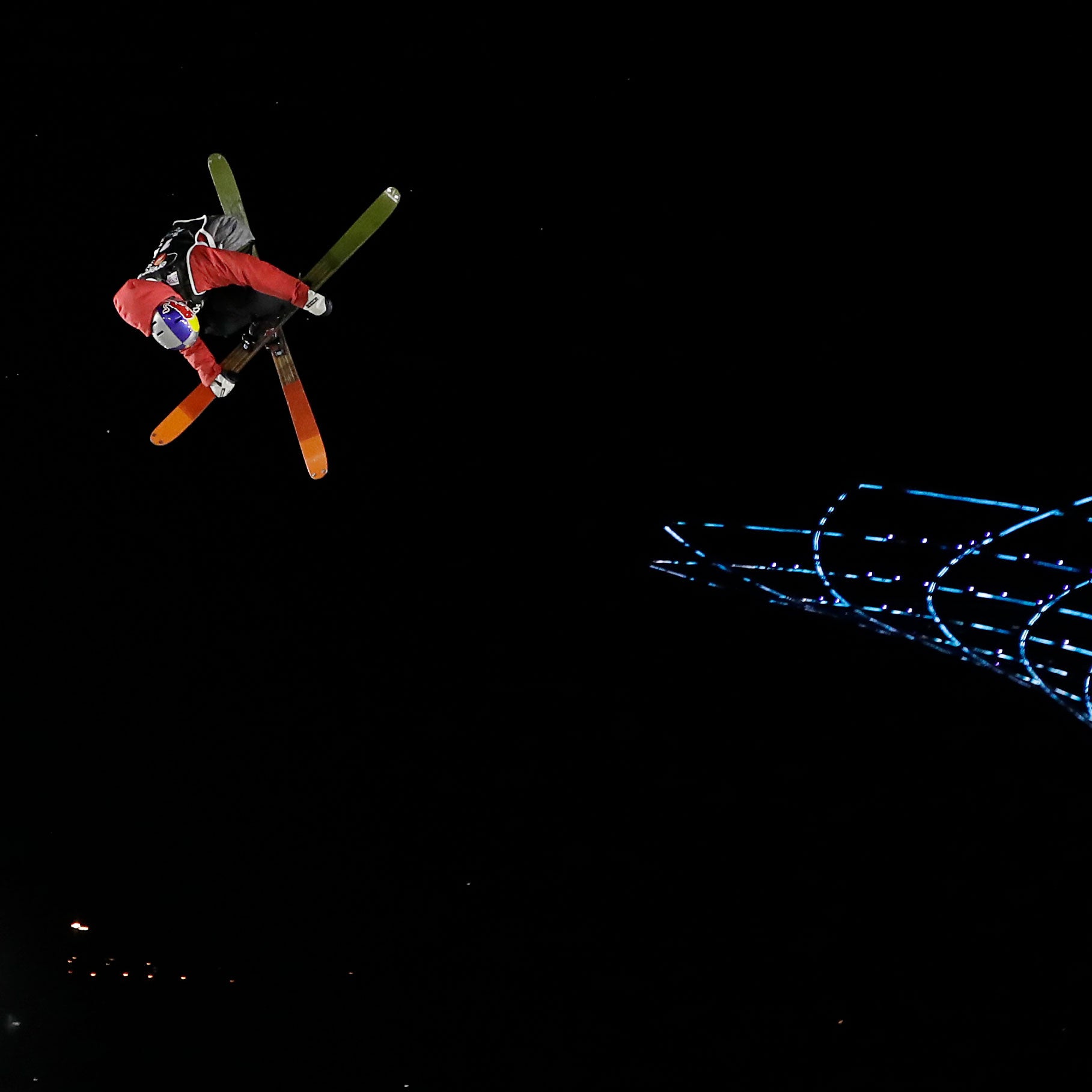

For Sargent, as for many others, K2 stands at the heart of the issue. Founded in 1962 by brothers Don and Bill Kirschner on Vashon Island, Washington, K2 gave America a hometown ski manufacturer to compete with the European brands. The company pioneered new ski designs and created a culture of cool that featured many of the greatest skiers in modern history, from Olympic racers Phil and Steve Mahre to freeskiers Glen Plake, Seth Morrison, and Sean Pettit.

Morrison’s tweet in September that he had been cut from K2’s roster��was the ��that the brand��was in trouble. But some��argue that K2 had started losing its greatest asset—soul—a decade ago.��Two former employees, who spoke on��condition of anonymity because they remain loyal to��K2, if not its new owners, say the brand has gotten increasingly corporate. “In the past four years, the corporate tentacles had really dug in and sucked the life out of everything,” one ex-staffer says.��“It got to a point where everybody had seven jobs, everybody was underpaid, no one knew if they were going to have a job on Friday. With layoffs and stuff, you just never knew what was going to happen. But the brand was so great that you stuck with it, and that’s why they still have people there.”

Not everyone feels this way, of course. Draper, who's worked with K2 for 21 years, says the uncertainty “seems to be more of a story outside than it is inside” the company. “We’re marching, and everybody here is really pumped. We have a lot of seasoned people, and we also have a lot of fresh eyes. The attitude is really as high as it’s been in ages.”

As the company strayed further from its roots, many of its longest tenured staffers grew disgruntled. Some left; others were laid off.

K2 has a history of its bottom line infringing on its soul. Most notably, “America’s ski company” moved its production facility from Vashon Island to China in 2001. But when Jarden bought K2 in 2007, the company’s approach shifted from “doing things to build the brand to being very heavily product and sales focused,” one former employee says.��

One example is��how K2 allowed its employees to promote��sponsored athletes.��Morrison had long been one of the faces of the company, but over��the past four years, employees couldn't post an image of him on social media if it showed the logo of his goggle sponsor, Oakley. Why? Because K2 made goggles. “They just didn’t understand the business,” an��ex-employee says of Jarden, which also owned Mr. Coffee and Crock-Pot when it bought K2.��

As the company strayed further from its roots, many of its longest tenured staffers grew disgruntled. Some left; others were laid off. Multiple ex-employees declined to talk about K2 for this story. Those who did spoke of sadness more than anger.��

K2 is not alone in the ski industry—or the outdoor industry—when it comes to corporate consolidation. The trend has impacted ski resorts, too. (See: Vail Resorts’ purchase of Whistler Blackcomb for $1.1 billion this fall.) But as an��ex-K2 staffer points out, “At least the resort people want to make money off of skiers. I feel like [the Newell situation amounts to] bean counters who really don’t give a fuck. They’re just like, ‘Dude, let’s get these off our books, we don’t want to have to deal with these brands.’”

A spokesperson for Newell declined to say whether the brands were being sold as a group or individually. But Jason Levinthal, founder of Line skis, wrote in that he inquired with Newell about buying Line and Full Tilt and was told he would have to buy the entire snowsports portfolio. Sargent said he knows of potential buyers who are considering the portfolio, but he declined to name them.��

Late last month, the Newell spokesperson sent a public statement promising the parent company would not shut down the brands if they don’t sell. But many insiders remain skeptical. Even Draper, when asked if he believed any brands within K2 would be shut down if they fail to sell, says he doesn't know what will happen.��

Until something concrete happens, the ski��industry waits with a mix of intrigue and fear. Sargent, like others, believes the best outcome would be for a group��of skiers or snowboarders to buy K2 and the rest of the brands. He is tired of outside investors placing “unrealistic expectations” on snowsports brands. “Everybody’s trying to make more money out there, and I get the consolidation and I get [venture capital] money in our space, but at the expense of destroying the industry? I don’t agree with that.”

Levinthal guesses that whoever buys Newell’s snowsports portfolio will ultimately break up the brands and sell them individually for a profit. K2, which just opened a multimillion-dollar development center in Seattle, could make a prime investment target for someone who understands the brand’s legacy, in addition to its sales numbers. At least that is what everyone in the ski industry hopes, including K2’s former employees.��

“I really do feel like the brand is going to survive. The brand is going to do well,” says one ex-staffer. “The brand is too strong. There’s too much life in it.”