In March, Thomas Panek finished the New York City Half Marathon. What made that feat remarkable wasn’t the distance—Panek has run several full marathons—or his 2:20:51 time, or even the fact that he’s blind. What made Panek’s accomplishment unique was that it was the first time a half marathon has ever been completed .

The milestone didn’t come about because of developments in training and conditioning, for either the human or the dog: it was all thanks to the dog’s harness.

“The harness hadn’t been changed since the horse and buggy,” says Panek, the president and CEO of Guiding Eyes for the Blind. The leather and metal harness so indelibly associated with guide dogs first came into use during the 1930s. In material and construction, it closely resembled the type of harness used to tether a horse to a carriage. But a dog isn’t a horse and a human isn’t a buggy. “It’s like wearing wooden shoes,” Panek says. “You might be used to it, but it’s probably not the best thing for you or the dog.”

Panek lost his sight in his early 20s. At 48, he’s had a long time to figure out everything wrong with those traditional harnesses. “Problem number one is that it’s designed after a pulling harness for a horse,” he says. The leather strap that runs around the front of the dog restricts its movements, preventing the animal from achieving its full stride while running. The harnesses are uncomfortable for dogs to wear over long periods of time, and typically cause permanent hair loss beneath the belly strap.

“Problem number three is the weight,” Panek says. While weights vary according to the size of the dog and the human it’s guiding, leather and metal construction aren’t exactly athletic wear, no matter how fit you are.

Finally, there’s the fixed handle, which sits perpendicular to the dog. “That’s okay when you’re walking somewhere, but if you’re going to be running, you can’t have one hand out in a static location, uncomfortably twisted,” Panek says. The fixed distance is especially an issue for a runner tackling a serious climb; going uphill dictates a shorter handle than going down.

The sum of all those problems was a general consensus that a guide dog could never lead its blind owner on a run. Plenty of blind people have completed marathons and enjoy recreational running, but until March, all of them did that using human guidance.

But Panek didn’t understand why one would their leave at dog at home during a run, and set about solving the problem.

Some early attempts included hanging a hula hoop around his waist, as sort of an early warning system of incoming obstacles, and using semi-rigid refrigerator pipe in place of the traditional fixed harness handle. Then he discovered that Ruffwear had already developed an ideal harness for athletic dogs with its .

That harness was designed to faciliate the dog’s comfort and natural range of motion, but Panek soon found that running with it attached to a traditional leash was “like pushing on a rope.” When one of his guide dogs would try to bring him to a stop, to avoid an impending obstacle, he’d keep going, crashing into whatever was in the way. “We had to come up with some creative way for the dog to give me feedback,” he says.

Because he’d already identified the Front Range as one part of his ideal solution, Panek reached out to Ruffwear to help him find the ideal way to connect dog and runner. The company loved the idea, and offered the help of Timothy Gorbold, a former aerospace engineer who’s now a product designer for Ruffwear.

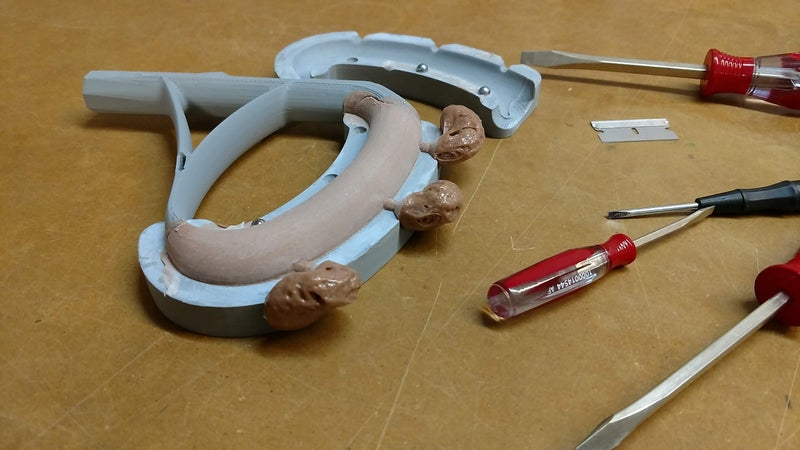

Panek and Gorbold started running together, and working on a solution. Slowly, what would become the Unifly took shape. Based on the Front Range, it adds a flexible, internal frame inside the top half of the harness to distribute the load on the dog, and to better transfer signs fo the dog’s movements to the human. In need of a solution for quickly attaching a pole to that harness, while allowing for total freedom of movement, Gorbold adapted a binding from a nordic ski to the purpose. Rather than a big metal hoop, connection between human and harness is handled by a lightweight aluminum pole that’s similar to a hiking pole in construction, and which easily adjusts in length. Then Gorbold and Panek spent a ton of time perfecting an ergonomic handle, which can freely rotate as the runner moves, but which won’t cause discomfort on long distance runs.

The end result is a system that is comfortable and light for the dog, and that allows the human to swing their arms in a natural motion while running. It also provides much better feedback and resistance—Panek says the dog pushes against you as it slows—than was ever achieved by the “horse and buggy” original.

The Unifly offers advantages beyond running marathons. Panek says the huge leap in comfort and communication means it’s better in every other circumstance too. It’s simply a new, much better way for the vision impaired to work with their seeing eye dogs.

To complement the Unifly, Ruffwear has launched . There’s a flashing beacon with audible on-off signals, so a blind user will know it’s working. There’s a service dog ID vest that’s again modeled on the Front Range. And even a waist-worn treat dispenser for hands-free training reinforcement. All are only available through accredited guide and service dog organizations.

In addition to the half-marathon, Panek is now able to enjoy regular runs with his dogs, and is even able to venture off pavement with them for trail runs, on challenging terrain. Thanks to the Unifly, he’s even run down Oregon’s Mt. Hood using only a dog. This additional freedom is hugely empowering, but also incredibly simple. I asked Panek how it felt, to which he simply responded: “What’s better than running with your dog?”