In 2010, a French adventure racer named Nicolas Mermoud approached , the accomplished American ultrarunner, and asked him to try out a pair of running shoes he’d designed. They looked bizarre, like moon boots, and were wider, thicker, and softer than typical running shoesÔÇötwo and a half times beefier and 30 percent cushier. Meltzer, who had been training with conventional running shoes, was skeptical, but he laced them up and cruised around his Sandy, Utah, neighborhood. He was shocked by how forgiving they were. Halfway through the run, he was sold.

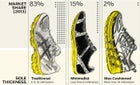

Running Shoes by Market Share

Within three months, Meltzer dropped his sponsor, La Sportiva, which specializes in lightweight trail runners, and started competing in Mermoud’s creation, the Hoka One One. The shoes gave Meltzer’s career new life, and by April 2011, he’d won his first race in a yearÔÇöa brutal ┬ş26.2-mile trail run in Utah. Three weeks later, he won a 100-miler in Virginia, followed by a ┬şvictory at Alabama’s Pinhoti 100 in November. “People thought they looked like clown shoes, but I didn’t care,” he says. “I could float over rocks and not feel anything.”

Meltzer’s wins came at a time when barefoot running, the biggest fitness trend in years, was hitting its zenith. Sales of minimalist shoes had exploded by more than 400 percent. But he was just one of many max-cushion converts. In the past two years, more than a dozen elite ultrarunners have begun racing in Hokas, including 38-year-old ┬şDarcy ┬şAfrica, who won the 2013 Hardrock 100 in a pair, and Dave Mackey, who captured two victories last year at age 43.

A growing number of amateurs have followed their lead. In 2010, the first year ┬şHokas were available to the public, the shoes were being sold in 80 specialty running stores worldwide. In 2013, over 350 dealers were stocking them, including REI and Road Runner Sports, with 32 U.S. locations. At Utah’s last July, a third of the 275 runners who crossed the finish line were sporting Hokas. All of which has industry insiders wondering if Mermoud’s creation will derail the minimalist running revolution.

ÔÇťMost runners are looking to feel healthy and have fun. For them, a shoe that’s more forgiving is a better shoe.ÔÇŁ

“When the minimalist movement hit, people were excited to try it,” says Mark Sullivan, editor of , which covers the industry. The surge of interest caught many by surprise. In 2010, minimalist running shoes represented a third of the overall market. Then the blowback began. A number of runners who made the switch without adopting proper formÔÇö┬şleaning forward and taking shorter stridesÔÇösuffered injuries. By 2013, market share had fallen to 15 percent. Runners who just wanted to head out the door and not worry too much about technique began gravitating back to traditional shoes. “Most runners are looking to feel healthy and have fun,” says Sullivan. “For them, a shoe that’s more forgiving is a better shoe.”

Mermoud and his business partner, Jean-Luc Diard, didn’t set out to take down minimalist running when they launched Hoka in 2009. The duo had been competing in adventure races and envisioned a shoe that would be the equivalent of a downhill mountain bike or a powder ski. “Mountain bikes addressed tough terrain with big tires and shocks, and oversize skis allowed you to float,” says ┬şDiard, 56. “We wanted to make a shoe that worked the same way.”

Their first obstacle was creating a foam that was thick and soft but also light. For that they tapped a chemist at a Chinese shoe manufacturer, who set about reimag┬şining the squishy ethylene vinyl ace┬ştate found in most shoesÔÇöusing proprietary chemicals and applying different baking methodsÔÇöuntil he’d created a sole with 29 millimeters of cushioning, a 19-┬şmillimeter boost over traditional shoes, without any ┬şadded weight. Then they included extra rocker to the sole, allowing for better forward propulsion. The resulting shoe, the Hoka One One (named after a Maori phrase meaning “to fly”) appeared at a moment when ultrarunners were growing in number. “They were our first adopters,” says Diard, “But we’re seeing more and more athletes from different sports using our shoes for training.”

In October 2012, Hoka was acquired by , the billion-dollar company behind and . At the time, Jim Van Dine, the man put in charge of the new division, said that Hoka could become a $100 million brand, putting it on par with or . Since the takeover, sales have spiked by 400 percent, from $2.2 million to over $10 million, despite the fact that a pair of Hokas run $160ÔÇötwenty or thirty dollars more than typical running shoes. The success has spurred a handful of competitors to rush development of their own max-cushioned shoes. In December, Altra debuted the Olympus, with a 32-┬şmillimeter sole. The similarly sized Brooks Transcend and New Balance Fresh Foam come out in February, and the Vasque ShapeShifter Ultra in March. Hoka’s latest model, the Conquest, is available in January.

To date, there has been almost no scientific research on the benefits of oversize soles. Anecdotally, runners report a more relaxed ride and reduced recovery times after long runs or races. And many runners with chronic injuries say the shoes have let them run comfortably for the first time in years.

Not surprisingly, diehard minimalists aren’t buying into Hoka’s bigger-is-better concept. Some critics contend that the soft foam absorbs too much of the energy runners use to propel themselves forward, ┬şespecially on the flats. “Minimalist shoes teach you to use your body to cushion impact,” says Irene Davis, director of the Spaulding ┬şNational Running Center at Harvard Medical School and a close colleague of Dan Lieberman, barefoot running’s founding philosopher. “These shoes don’t teach you that. As the cushioning wears out after 200 or 300 miles, the aches and pains will start.”

Of course, that sounds a lot like what traditional runners were saying back when the minimalist movement was taking off. That injuries have been a part of the trend has done little to slow sales. Whether or not max-cushioned shoes ever get as popular, despite higher cost and the possibility of injury down the road, is the billion-dollar question. “Every┬şbody is watching this category closely,” Sullivan says. “If it continues to be successful, we’ll see just about every brand with some version of these shoes.”