After months of research and countless meetings and back-and-forth emails between ���ϳԹ���‘s editors, writers, and gear testers, we’ve assembled our first-ever list of the most important gear ever created. These are the products and innovations that have made it possible for those who inspire us and those who read us to live a more active life.

We’re sure this top 100, which is presented in chronological order and goes all the way back to 860 B.C., won’t be without controversy. We’re hoping you’ll chime in with your own additions and changes—in the comments section, over email, with old-fashioned letters, through Twitter and Facebook, and all of the other ways in which you’re used to contacting us. We’ll be watching and collecting notes for when we revisit this list in the months and years to come.

Personal Flotation Device: 860 B.C.

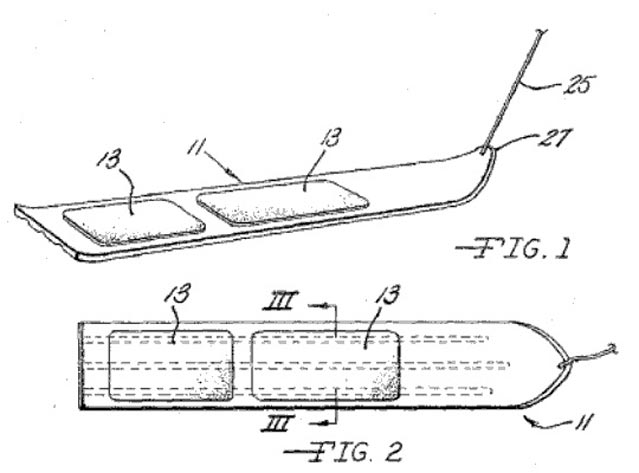

Though modern personal flotation devices (PFDs) were developed for the military, reliefs in London’s from the 9th century B.C. depict enemies of the Assyrians swimming the Euphrates River supported by inflated goat skins, which may have been the original PFDs. European naval commanders were hesitant to carry PFDs aboard, fearing they would enable desertion. However, by the 19th century, Norwegian vessels carried wood planks and cork blocks to help save sailors in the event of a shipwreck. In 1841, the U.S. Patent Office issued for “Improvement in Buoyant Dresses or Life-Preservers” to New Yorker Napoleon Edouard Guerin for a double-layered jacket, waistcoat, or coat hat that could be stuffed with 18 to 20 quarts of cork, and the modern life jacket was born. Most PFDs now use air or foam to aid flotation.

Friction Matches: 1827

In 1827, English Chemist John Walker stumbled upon a mixture of chemicals that could ignite on any surface once it had dried. However, the invention did not prove lucrative to Walker, who never secured a patent on his product and only managed modest sales of his flammable “Congreves.”

Three years later, Charles Sauria developed white phosphorus matches. While effective, the fumes were poisonous, and gave users an ailment known as “phossy jaw.” It wasn’t until 1910 that Diamond Match Company patented the first non-poisonous match. At the public request of President William Howard Taft, the company relinquished its patent a year later and surrendered its monopoly on safe matches.

Rubber Raft: 1845

Humans have been building rafts for thousands of years—some scientists suggest that the first rafts were constructed 800,000 years ago—but it wasn’t until the early 1840s that developed a rubberized raft that he used to explore the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Rubber rafts were relatively light and collapsible, and they improved on rafts constructed from cloth tubes with a wrap-around floor. The first known use of a raft in whitewater was in 1842, when Freemont set out to survey the Platte River in Wyoming for the . By the turn of the 20th century, the first commercial rafting outfits were springing up around the country.

Spork: 1874

The search for the single perfect utensil is more than a century old. Samuel W. Francis filed the for a combined spoon, fork, and knife in 1874. Others tinkered with his designs (with sometimes dangerous results). The term spork first surfaced in 1909, but it wasn’t until 1952 that Hyde Ballard copyrighted the name. Today, it’s a beloved accessory for car campers and weight-conscious alpinists alike—though you’re most likely to use one if you’re dining in a hospital or high school.

Safety Bike: 1876

Colonel Al Pope, a former officer in the Union Army, fell in love with high-wheelers at the 1876 in Philadelphia. Using money he’d made in the post-war shoe industry, Pope started collecting bike patents, importing bikes from England, and finally manufacturing them himself in an old sewing machine factory he turned into a bike factory.

The safety bicycle was different from other two-wheeled human-propelled vehicles because it positioned the rider low between the wheels where he or she could propel the bike with a sprocket and chain rear-wheel drive system. This basic diamond frame rear design is still standard.

Eventually, Pope’s safety bike frame design was coupled with inflated rubber tires that made the ride a bit smoother than did the previously used solid rubber. was the first to mass-produce a bike in this general style in 1895, and bring “the joy of biking to the masses.” The price of bicycles dropped steadily as manufacturing methods improved, making them suitable for both business and pleasure—transportation and recreation for people of all income brackets.

First Slalom Skis: 1879

is considered the father of modern skiing. Born in the small village of Morgedal in Telemark, Norway, Norheim displayed an early talent for the one-day sport—at that time it was mostly used for transportation—and craftsmanship. As a young boy, Norheim made what may well have been one of the world’s first ski jumps, launching off the roof of his parents’ cottage on two straight pine skis made by his father. But he soon found that he needed better equipment to tackle steeper hills and to make tighter turns, so he experimented with a tight fitting birch binding and ended up shaping a short, curved, flexible ski for easy turning in soft snow. In 1868, when he was 43, Norheim won the first Norwegian national skiing competition in Christiania (now Oslo) on skis he built himself. It took almost 40 years for Norway’s neighbors to adopt skiing as recreation, but by 1924, the ski jumping and the Nordic combined events were a part of the inaugural .

Primus No. 1 Stove: 1892

Frans Wilhelm Lindqvist, a factory mechanic in Stockholm, Sweden, developed the first portable pressurized-burner kerosene (paraffin) stove. He tinkered with the design of a hand-held blowtorch, and partnered with Johan Viktor Svenson to manufacture the Primus Number 1. Their creation quickly gained a reputation as a durable solution for cooking in extreme conditions. , which works by preheating the stove to vaporize a flow of kerosene before it reaches the burner, has become standard in portable equipment.

All of the great explorers almost always had a Primus stove on them: Mallory and Amundsen each took one to the South Pole, Norgay and Hillary used one on the first ascent of Everest, and Byrd took his to the North Pole.

Later, inspired by Primus, Swedish manufacturer SVEA made the , a liquid-fuel, pressurized-burner camping stove that was the first compact backpacking white gas stove, and one of the most popular camping stoves ever made.

Victorinox Swiss Army Knife: 1891

Seeking to create a domestic version of the pocketknife carried by German soldiers, Swiss cutlery company began manufacturing the Soldier’s Knife in 1891. It had four basic folding tools: a blade, an awl, a can opener and a screwdriver. Six years later, the company created its now-iconic Swiss Army Knife. This larger tool, patented as the Officer’s and Sports Knife, featured a second, smaller blade and a corkscrew. Though the Swiss Army Knife was never manufactured for military use, Victorinox’s Soldier’s Knife is still standard issue in the Swiss army.

Grivel 10-Point Crampon: 1908

Hunters and soldiers have used rudimentary crampons since the Roman Empire. But it was English engineer and mountaineer that made them what they are today. Starting in 1908 Eckstein published articles in Ostereich Alpenzeitung—the Austrian Alpine Journal—detailing the results of his research on the manufacture of crampons, their systematic use, and the incredible feats they could perform. He brought his plans for the first 10-point crampons to Henry Grivel, a blacksmith whose family had been producing equipment for alpinists since 1818. They gained a huge following. By June 1912 a competition for “cramponneurs” was organized on the Brenva glacier with Eckenstein judging. Grivel couldn’t patent the new designs because mice had eaten the original drawings, but the family company, , continued to improve upon the design. In 1932 Henry’s son, Laurent, added dual front points to the crampon, which has become standard for vertical ice climbing as well as mountaineering.

Bergans of Norway Rucksack: 1908

Ole F. Bergan held 45 patents for outdoor gear—for everything from the first step in/step out ski bindings, an electrical whaling harpoon, a log sled with brakes and a valve-free combustion engine, and the frame pack—so he was used to devising quick and original solutions to problems when he ran into trouble on a hunting trip. Out on the trail one day in 1908 Bergan’s load felt particularly heavy, so he created an impromptu backcountry prototype of a framepack using a juniper branch that he bent into the back of his pack for additional support.

From this first prototype Bergan developed the framepack idea, replacing the branch with light tubular steel and straps. His idea was that the sack should be shaped according to a person’s form and height, and that it should sit snugly against the body while supporting the load. A few years later Sverre Young bought the patent from Bergan and osld a considerable number of rucksacks to the Czechoslovakian army. , Ole’s manufacturing company, made the packs. When the patent ran out after 25 years, other pack manufacturers immediately copied Ole’s design.

Carabiner: 1910

It took a climber’s eye to turn carabiners from a military tool into revolutionary gear. As early as the 1850s, German firefighters used carabiners for anchoring purposes, but various soldiers had already been using the metal clips to hold up their guns for decades.

In 1909 Otto “Rambo” Herzog saw firefighters practicing rescue with carabiners, and he immediately saw their potential for climbing applications. Up to that point, climbers had to untie their ropes and re-thread them through protection or use a second piece of cord to tie their protection and rope together. This often required two hands, and limited the difficulty of climbs that could be safely completed. Using carabiners, Herzog was able to establish routes—now graded as hard as 5.10.

L.L. Bean Maine Hunting Shoe: 1912

Avid outdoorsman returned from a hunting trip with cold, damp feet and a revolutionary idea. Bean enlisted a local cobbler to stitch leather uppers to rubber workmen’s boots lowers to make a durable and weather-resistant boot suitable for exploring Maine’s woods.

In 1912, working out of the basement of his brother’s apparel shop, Bean obtained a mailing list of non-resident Maine hunting license holders and prepared a three-page flyer that boldly proclaimed, “You cannot expect success hunting deer or moose if your feet are not properly dressed.” He touted his as designed by a hunter who has tramped the Maine woods for the last 18 years—referring to himself. Bean guaranteed that the boots would give hunters “perfect satisfaction in every way.” Of the 100 orders that came in for his new product, 90 were returned when the rubber bottoms separated from the leather tops. Bean refunded the purchase price, borrowed more money, corrected the problem, and mailed more brochures.

Stanley Insulated Bottle: 1913

“Be it known that I, William Stanley … have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Heat-Insulated Receptacles,” wrote the founder of in to the United States Patent Office. His innovation, discovered while he experimenting with welding, was to insulate vacuum bottles with metal instead of glass. “The common vacuum receptacle has its shells or walls constructed of glass and accordingly such receptacles are very liable to breakage and cannot withstand hard usage,” he noted.

By 1915, the Stanley company was mass-producing metal-insulated vacuum bottles. They were quickly adopted by the U.S. military, and the bottles were commonly carried aboard B-52 bombers in World War II. In 1995 William Stanley was inducted to the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame for his work on over 129 patents.

Adidas Sprint Shoe: 1925

Twenty-year-old athlete Adolf Dassler, it seems, was driven to provide every track and field athlete with the best footwear for his or her respective discipline. He made his first shoe from canvas. In the mid-1920s, he experimented with spikes in his shoes’ soles. Athletes wore them for the first time competing in the in Amsterdam. Lina Radke-Batschauer won an Olympic gold medal in Adidas shoes, running the women’s 800m in world record time. Dassler’s spikes, as Radke-Batschauer’s time demonstrated, gave athletes better traction.

By the mid-1930s “Adi” Dassler was making 30 different shoes for 11 sports, and he had a workforce of almost 100 employees. The in Berlin were another big win for Adidas. set new records in Adidas shoes in almost all of the 12 events he competed in. Owens, an American, was lauded as the most successful athlete in Berlin, winning four gold medals in Dassler’s shoes.

Dassler made the first post-war sports shoes in 1947 using canvas and rubber from American fuel tanks. But his biggest breakthrough of all was when the German team, , won the in 1954. It was raining, and the Hungarians struggled in heavy, rain-soaked boots with studs too short to grip the muddy field. The Germans scored the game-deciding goal in shoes with more grip. Plus, the shoes reportedly gave players a better feel for the ball, thanks to Adidas’ thinner leather upper.

Metal-Edge Skis: 1926

One day in 1917 was preparing for a steep, icy run just south of Salzburg, Austria. To his dismay, the worn-down edges of his hickory skis wouldn’t hold an edge. He elected to slide down, and found that he could only control his momentum by digging in the metal tip of his ski pole. That experience hatched the idea for a metal-edged ski. After nearly a decade of tinkering, Lettner found that he could preserve a ski’s flex by screwing small steel edge segments to the wood. He built a ski that could cut through snow for tighter, faster turns. Though he patented his design in 1926, the market was soon flush with similar models, and by the early 1930s, metal-edged skis were ubiquitous.

Campagnolo Bicycle Components: 1933

In November 1927, with snow covering the roads of the Italian Dolomites, competed in the Gran Premio della Vittoria race. Crossing Croce D’Aune Pass he needed to change gears, which at that time entailed removing the rear wheel. Large wingnuts that held his wheel on were frozen, and his hands were too cold to loosen them. Unable to shift, Tullio lost the race, muttering words to himself that would change the course of cycling: “Something must change in the rear!”

In 1930 Campagnolo produced the first quick release, after which he invented the first derailleur. By 1940 Campagnolo had developed the shifting system, which was a derailleur that used two levers and rods attached to the right-side seat stay. While riding, the cyclist would reach down and use one lever to open the quick release and the second fork-like lever to move the chain, which would shift it between cogs, and push the rear wheel backward or forward.

DuPont Nylon: 1935

Dr. Wallace Carothers, the head of ’s research division, sought a fiber that stood up to both heat and solvents. During his research, he became the first to synthesize nylon. Originally, DuPont determined that the fiber was best used to replace silk in women’s hosiery. The first batch of nylon staple was delivered to a commercial knitting mill under conditions of extreme secrecy—the chemist carrying the staple slept with it on his person on the overnight train ride to the mill. In the first year of production, DuPont sold 64 million pairs of stockings. During World War II production was channeled away from pantyhose and into parachutes and B-29 bomber tires. Following the war, nylon appeared in a wide range of consumer products. Today, it’s used in gear ranging from climbing ropes to jackets to tents.

Ray Ban Aviator: 1936

In 1929 the celebrated General Nevil Macready asked for a new type of air force eyewear that would protect pilots from glare at high altitudes while at the same time ensuring their clear field of vision. The company developed lenses that could block out a high proportion of visible light. The first publicly available model released had the signature Ray Ban shape we all know today.

Eddie Bauer Blizzard-Proof Down Jacket: 1936

was fishing with his trapper friend Red Carlson on the North Fork of the Skokomish River in Washington in 1935 when he nearly died of hypothermia. The pair had caught 100 pounds of winter-run steelhead when they headed back to the car a mile from where they were fishing. It was a 200- to 300-foot climb out of the steep river canyon with the fish and their gear. It was snowing, but the men were overheating from the exertion of the trek, so they took off their heavy wool mackinaws. Bauer’s shirt became soaked from the sack of fish and sweat. By the time he reached the top, his cotton long johns had frozen and his body temperature was dropping. He stopped to rest against a tree and immediately started to fall asleep. Realizing that he was dangerously hypothermic, Bauer fired three shots into the air with his revolver to alert Carlson, who was out of sight. Carlson revived his friend and got Bauer back to the car.

When Bauer was a boy, his Uncle Lesser had told him stories of serving in the Russian army during the (1904-05) in Manchuria, and about the down-filled coats the Russian officers wore to keep warm in the bitter winters. And by the time of that 1935 climb, when he remembered these stories, Bauer had already been working with feather and down merchants making his own custom fishing flies and badminton shuttlecocks. He cut a pattern for a jacket that he thought would fit him and had a seamstress make a prototype from his pattern with diamond-shaped baffles to keep the down in place. When finished, Bauer delivered the jacket to one of the renowned mountain climbers in Seattle at that time, Ome Daiber, who loved it, and then went to work manufacturing the first jackets for Bauer until he couldn’t keep up with the volume of orders. And so, in 1938, Bauer formed Arctic Feather & Down Co. to manufacture his down jackets. “If I didn’t trust a piece of equipment, it wasn’t stocked,” said Bauer. “If I needed equipment that wasn’t available elsewhere, I developed it myself.”

When Bauer introduced his down-insulated the extraordinary qualities of goose down—exceptional warmth, lightweight, breathability, compressibility and durability—represented a paradigm shift in cold-weather equipment. It had immediate applications in mountaineering, exploring, skiing, hunting and fishing, as well as for people who worked outdoors in winter: linemen, miners, oilfield workers, ranchers.

By the time Bauer had introduced what became his second and third patented down garments—a quilted, hooded parka and matching quilted pants that were called, respectively, the Bauer Down Parka and the Bauer Down Flight Pants—Germany had invaded Poland, and World War II was underway. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the U.S. government froze the commercial use of feathers and down and appropriated all the domestic supply for the war effort. By that time, a significant part of Bauer’s business was making down garments and sleeping bags, which he then sold to the U.S. Army—more than 200,000. That military connection helped to quickly broaden Bauer’s name recognition beyond the regional renown he’d earned in the Northwest. When mountaineers and skiers returned to the mountains after the war, Bauer’s goose down clothing and sleeping bags were perfectly poised for the Golden Age of Himalayan Mountaineering, as it became known. In 1953, when Charles Houston led the in an attempt to make the first ascent of K2, three of the eight climbers on the team were from Seattle. They came to Bauer to ask if he could build them special down mountaineering parkas.

Vibram Soles: 1937

The leather-soled hobnail boots and cleated felt-bottom climbing shoes of his day troubled Italian alpine guide and Milan retailer . When mountain weather changed, which it often did, climbers would be unable to descend, or their feet would freeze. Bramani believed that rubber, like that used in car tires, would have better slip resistance as well as improved thermal protection. His first rubber soles mimicked hobnail soles. He sold them exclusively in his shop, using the same gold label on the bottom of the boots that he used on his clothing.

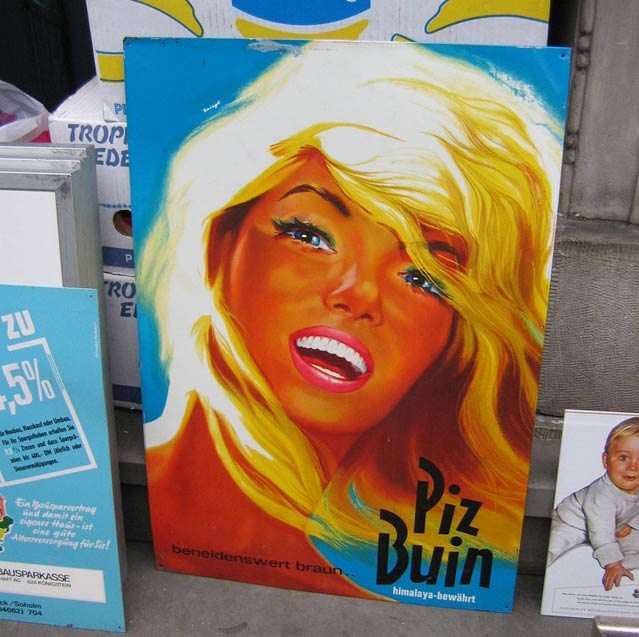

Sun Protection Cream: 1938

In 1938 after scaling Piz Buin, a 3,312-meter peak on the border of Austria and Switzerland, Franz Greiter suffered from bad sunburn. A chemistry student and passionate mountaineer, he worked to develop a lotion that would mitigate the sun’s effects and began marketing his Glacier Cream under the brand name in 1946.

The issue of who truly invented sunscreen is still hotly contested, though, as at least three other scientists—including Eugene Schueller, founder of —had worked on similar ideas as early as 1930. Nevertheless, Greiter is definitively credited with developing the notion of Sun Protection Factor (SPF) that is now the standard for measuring a sun protection product’s effectiveness. To celebrate its 65th anniversary, Piz Buin’s Glacier Cream, now called , was relaunched with a higher SPF.

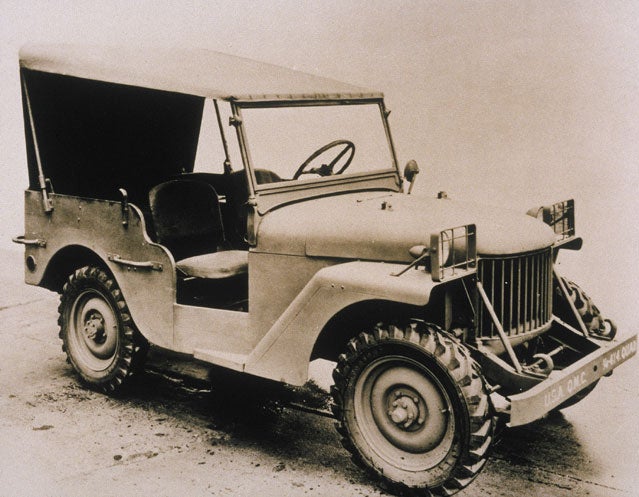

Jeep SUV: 1940

In July 1940 the invited 135 car manufacturers to bid on building a “light reconnaissance vehicle” to replace the Army’s motorcycle and modified Ford Model-T. , , and each won a portion of the lucrative government contract to create a four-wheel drive vehicle capable of uneven off-road driving. With modifications and improvements, Bantam’s Willys Quad was eventually known as the Jeep. The name either came from the slurring of the letters “GP,” the military abbreviation for “General Purpose,” or from “Eugene the Jeep,” a Popeye cartoon character.

Thule Roof Rack: 1942

In the midst of World War II, Swede Erik Thulin taught himself metalworking and established to make fish traps, belt buckles, and headlamp grills. When the automobile boom hit in the late 1950s he developed the first easily transportable modular roof basket that was also affordable thanks to die cast zinc fasteners that were significantly cheaper than stainless steel but sufficiently durable.

Grumman Aluminum Canoe: 1945

After portaging a heavy wood and canvas canoe on an Adirondacks fishing trip, William Hoffman, vice president of , made a canoe from the same lightweight, stretch-formed aluminum that Grumman used to become the largest producer of carrier-based fighter planes during World War II. By the end of the war Grumman was producing lines of 13-foot, 15-foot, 17-foot, 18-foot, 19-foot, and 20-foot canoes.

Dr. Bronner’s Liquid Soap: 1948

German Jew and third-generation master soapmaker traveled widely to speak out against religious intolerance. He lectured on soapboxes and in auditoriums, giving those who came to hear him speak an unlabeled bottle of his home-crafted peppermint liquid soap as a thank you. When he noticed people were coming for the soap and not the lecture, he wrote his philosophy on a label and glued it to the bottle so people would read it in the shower.

As his soap grew in popularity, Dr. Bronner went from making soap at home to secretly renting out a chemical factory just on Sundays to recruiting his son, Jim, to head soap-making full time at the factory. Because Dr. Bronner’s soap is biodegradable, it has become the go-to camping soap for backpackers and outdoor lovers. Not only is it safe for the environment, but it’s also tingly, refreshing and cooling on the skin.

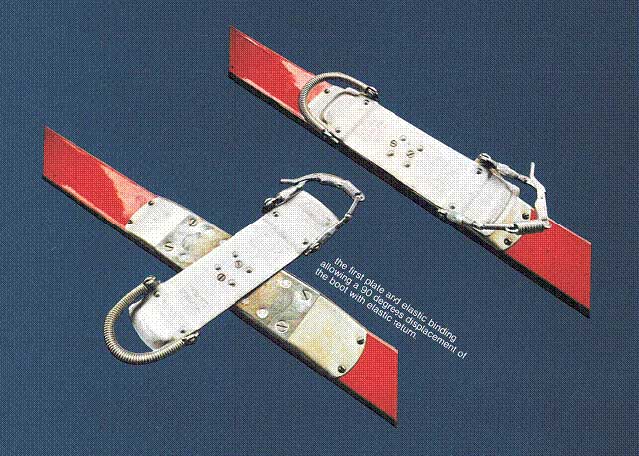

Look Nevada Releasable Ski Bindings: 1950

Ski bindings in the 1940s locked the boots to a ski in a way that even a seemingly innocuous fall could cause a fracture. Then Jean Beyl, founder of , designed a binding with a plate and a ball bearing under the foot to diffuse torque and reduce pressure on the knee. They were heavy, difficult to install, and weakened the ski, but had enough advantages that the French ski team competed in them in 1950.

Beyl’s next iteration of the binding used a C-shaped piece that fit over the toe of a ski boot, eliminating the underfoot bearing and plate. When a skier exerted sideways pressure in a twisting fall, the clip would rotate and release the boot. The body of the binding was also pivoted so that when a skier caught a tip the binding would release. The Nevada toe was the first modern ski binding to work with any commercial boot. The design reduced knee injuries as well as lower leg fractures dramatically, and it’s the same basic system used today, with the addition of DIN settings that allow a skier to choose how readily his ski releases.

Neoprene Wetsuit: 1952

Ask who invented the modern wetsuit, and you’re opening up a can of worms. Jack O’Neill, a skylight salesman, wanted to surf longer in the chilly waves off the Northern California coast. He tried insulating his shorts with flexible plastic foam with some success. Then, a bodysurfing friend from a pharmaceutical lab introduced him to Neoprene. quickly ordered as much as he could get and began hand sewing it into a protective full-body suit. He opened San Francisco’s first surf shop in 1952, selling what he claims were the world’s first wetsuits. However, physicist wrote letters as early as 1951 discussing his invention of a neoprene body suit, though his patent application was never granted.

Hobie Alter Foam Surfboard: 1958

was a top paddleboard racer and surfer who made balsa wood boards in his garage with his friend Roger Bellknap. The duo constantly tinkered with design and materials. After opening his first shop in 1954 in Dana Point, California, with a total investment of $12,000, Alter was approached by Kent Doolitle, a Fiberglas representative who came by to show off a new material: urethane foam. When he saw how well it held up to acetone and resin—substances that destroyed Styrofoam—Alter started shaping boards with the new materials. By June 1958 he had figured out how to contain the foam in epoxy and orders for the boards began pouring in.

DuPont Spandex: 1959

Building on the work of William Hanford who, in 1942, discovered a process for synthesizing polyurethane, two scientists figured out how to create a new polymer that would eventually revolutionize exercise clothing. Seventeen years after Hanford’s discovery C.L. Sandquist and Joseph Shivers found that they could spin complex molecules comprised of polyurethane and polyurea, resulting in a fabric that could stretch up to 100 percent of its resting size yet snap back to normal. The new material was dubbed spandex, an anagram of expands. Textile manufacturers proceeded to combine it with practically every other fabric, from cotton and wool to silk and nylon. To this day, many blame the fabric for single handedly ruining fashion in the 1980s, but others celebrate it for making both outdoor and lifestyle apparel more comfortable and flattering.

Lange Plastic Ski Boots: 1962

Bob Lange, who worked at a polyurethane product manufacturing company, had the idea that using plastic in ski boots would give a skier more support and control of his ski than leather boots ever could. Building off of this idea, Lange experimented with using plastic as reinforcement in ski boots as early as 1958. Four years later, in 1962, he built lace-up ABS plastic shell boots. A female Vermont-based ski racer sponsored by Lange in the late 1960s said that the early boots “tortured everyone’s feet who wore them,” because the early boots had no hinging or give. They often caused stress fractures. This led Lange, in 1966, to create a boot with a thermoplastic shell, hinged cuff, and latching buckles that would become the first commercially successful replacement for leather boots. By 1970 boots were universal on the racing circuit, and Lange sold hundreds of thousands of pairs as the world’s leading ski boot brand.

Makaha Skateboards: 1963

During a stint at a boy’s home during the Great Depression, Larry Stevenson observed kids riding scooters made from girls’ roller skates nailed to wood with an orange crate balanced on top. Back home in Los Angeles, he saw kids riding the same scooters without the crates. As an adult, after surf bumming in Hawaii, Stevenson used these earlier inspirations to make a surfboard for the road, which he called a and advertised in surf magazines. At the 1963 National Sporting Goods show in Chicago, Stevenson’s five demo products earned him orders for 2,000 boards each day of the show. Before the next decade came to a close, Stevenson had sold more than 10 million units.

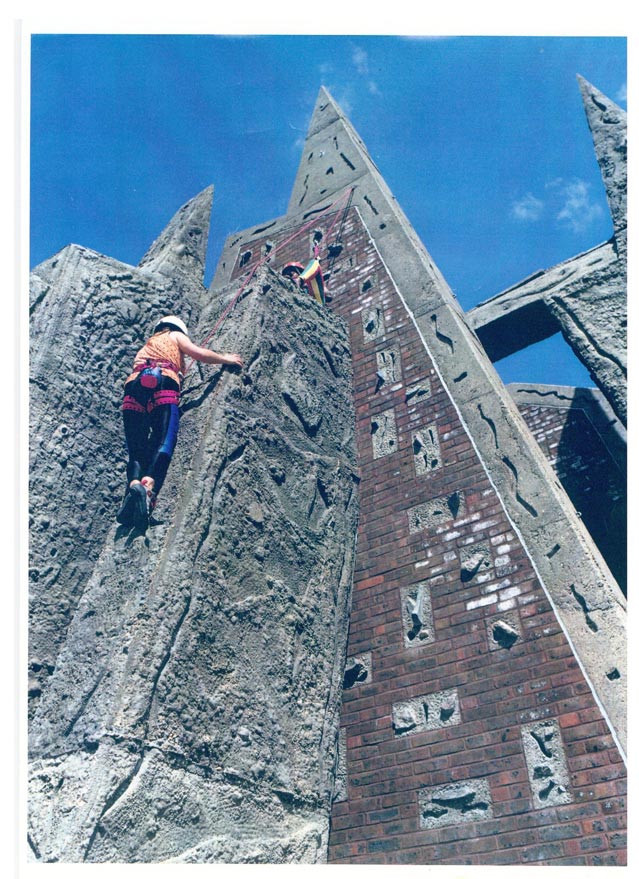

Indoor Climbing Wall: 1964

University of Leeds physical education teacher Don Robinson took his pupils climbing and spelunking near Sheffield, England, three seasons out of the year. However, the winter months away from the rock took their toll: Robinson’s climbers got hurt the most when they returned to rock after a months-long hiatus. To facilitate year-round climbing, he found rocks that simulated all different outdoor features—slopers, crimps, underclings—and, in 1964, built the world’s first indoor climbing wall out of found rock. Gaps in the stonework allowed indoor climbers to practice jamming. Nowadays, indoor climbing walls are primarily being built out of ¾-inch plywood, and holds are manufactured from urethane or resin.

Gatorade Sports Drink: 1965

In the summer of 1965, a University of Florida assistant coach sat down with a team of university physicians and asked them to determine why so many of his players were being affected by heat stroke. The doctors discovered two key factors: players were losing fluids and electrolytes as well as carbohydrates through sweat that they weren’t replacing. In the lab, the doctors formulated a new, carbohydrate-electrolyte balanced beverage that they named after the Gators, the university team, to replace what the players were losing in their sweat during exercise. Drinking the new formula, the Gators began winning, outlasting heavily favored opponents in withering heat and finishing the season at 7–4. Before the season ended, other college football programs started placing orders for the for their teams as well.

Snurfer: 1965

The Snurfer was the first iteration of the snowboard, conceived and built in 1965 by Sherman Poppen in Muskegon, Michigan. Poppen watched his 11-year-old daughter sled down a hill standing up and the proverbial lightbulb went off. In his shop, Poppen bound two skis together and tied a string to the nose of the board so the rider could have control. His wife coined it the Snurfer, and soon all of Poppen’s daughters’ friends wanted one of their own. By 1976 he had sold more than a million Snurfers at $10-$30 a piece. As the toy’s popularity grew, so did a small series of competitions, the first of which was called the “World Snurfing Classic,” held in 1968. The event caught the eye of a young Jake Burton. After finishing school, modified the Snurfer into the snowboard, founding a company that bears his last name.

Chouinard Clean Climbing Protection: 1972

As climbing grew in popularity in the 1960s, overused rock was starting to suffer. Climbers would often hammer metal pins—known as pitons—into the rock to aid their ascent, eventually widening or scarring thin cracks. In 1972, Yvon Chouinard, founder of Chouinard Equipment and , released a seminal catalog that sparked the clean climbing revolution. It advocated for the use of removable, low-impact protection. “It is the style of the climb, not the attainment of the summit, which is the measure of personal success,” wrote Chouinard. “The equipment in this catalog attempts to support this ethic…. Remember the rock, the other climber—climb clean.”

Skadi Avalanche Transceiver: 1968

The first electronic avalanche rescue beacon was a radio transceiver developed by a Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory research team headed by John Lawton. Previously, at least one American, an Englishman, and various Europeans had developed electromagnetic methods to locate avalanche victims, but their experiments and products lacked the range and accuracy needed to save lives. With a long-lasting battery, quartz frequency control, and a 90-foot range, the Skadi was significantly more accurate and reliable than its predecessors.

Ed Lachapelle inspired Lawton’s device, when, in the late 1960s, he built a small, pocket-sized radio transceiver that worked at the upper end of the broadcast band. His idea was to pick up that signal with a portable radio receiver using the receiver’s loopstick antenna for directivity. After seeing Lachapelle’s creation, Lawton assembled a pair of units using an audio frequency induction field with a playing card-sized pocket transmitter and a plug-in antenna—a wire coil one foot in diameter that could be sewn into the back of a parka. In Lachapelle’s tests, Lawton’s device worked. The large coil antenna gave more range than the Skadi that came to market, but it was awkward to use and limited the user to the chosen parka. Lawton downsized the unit by replacing the parka antenna with a smaller antenna built into the handheld plastic box.

Lowe Alpine Systems Expedition Internal Frame Pack: 1968

Greg and his uncle decided to try alpine-style ascents of Wyoming’s Tetons in winter as training for bigger peaks. Frameless rucksacks were too small to carry heavy loads, and external frame packs were awkward and unbalanced on technical terrain. So Greg built a frame stiff enough to transfer the load from shoulder straps to a hip belt like an external frame pack, but flexible enough to contour to the body and flex with the hips and torso while climbing. He put the frame inside the pack, adding hip and shoulder stabilizers, a sternum strap, and side compression straps—now all standard backpack features—to stabilize the load and bring it closer to the climber’s center of gravity.

Mountain House Freeze-Dried Camp Food: 1968

Oregon Freeze Dry (OFD), Mountain House’s parent company, supplied U.S. troops with freeze-dried long-range patrol meals (LRPs) during the Vietnam War. As the war wound down, the company sold excess military product in army surplus stores, and customers were clamoring for more. After Newsweek ran an article entitled “Gourmet C-Rations” in 1967 , interesting in developing LRPs for backpackers and campers, contacted the company. OFD and REI eventually teamed up to develop a line of camping LRP-style foods for REI stores that were marketed as . It launched with 14 original products.

Helly Hansen Lifa: 1970

Two Italian researchers working in the 1960s discovered a way to spin polypropylene into yarn. took advantage of the new technology and commercialized a hydrophobic baselayer that pulls moisture from the skin using O-shaped stitching on the inside and X-shaped stitching on the outside. The O-shaped stitching allows water to evaporate from the inside of the garment to its surface, where X-shaped stitching prevents it from reabsorbing.

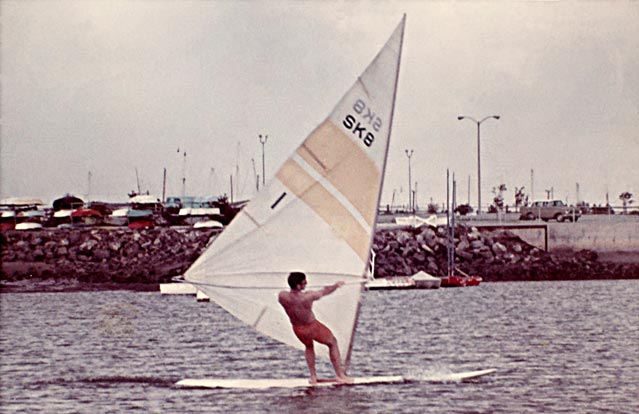

SK8 Windsurfer: 1970

It was a beautiful late afternoon in 1965 when Hoyle Schweitzer and Jim Drake gazed out on the Pacific to see blown-out surf. There were no waves to catch and there wasn’t enough daylight left to go sailing. They talked about how they liked the do-it-now aspect of surfing and the freedom of sailing, and wondered whether there was a way to combine the sports. Jim said he hated all the time required to sail: launch the boat, prep and rig, get out of the marina, then wash down at end of the day. Hoyle said surfing was restricted to wave conditions and finding a good break that wasn’t crowded. After a year of experimentation, they had a design with a fixed mast and no rudder that spoke to both their preferences. By 1970, armed with a patent, board sales started to take off, and Schweitzer and Drake had moved more than one million units by 1981.

Trak Waxless Nordic Skis: 1970

Bill Danner and Hans Woitscatzke, friends from Harvard, were looking one day for a winter activity that was environmentally friendly, healthy, cheap, and easy access. They were able to purchase a patent for a downhill ski covered in fish-scale patterns on the cheap because it had failed miserably; the ski went slower on the descent than ones without the strange pattern. But Danner and Woitscatzke saw something in the product. They were looking for an alternative to waxing, which they felt was the barrier to entry for Nordic skiing—both complicated and time consuming. They wondered if the pattern might let a Nordic ski climb without wax.

When testing proved that Danner and Woitscatzke’s idea worked, they took the design to several Nordic ski manufacturers. They all refused to build the ski for them. Finally, a German furniture building agreed to make the first pairs, gluing the polyethylene scale pattern onto the bases. Retailers hesitantly carried the , which were often stuck in a corner. But Danner and Woitscatzke had a solution for this too: They painted all of their skis bright orange so that they would catch a customers attention in both the store and on the trail. After Bill Koch won an Olympic silver medal in Trak skis in Innsbruck in 1976, sales went through the roof.

Kryptonite U-Lock: 1971

In the early 1970s the bike industry was booming and bike theft was on the rise. Thieves could cut chains and padlocks in seconds with basic bolt cutters available at most hardware stores. Cyclist Michael Zane was intrigued by a newspaper article he read in 1971 about Stanley Kaplan, a bicycle mechanic who had designed a new U-shaped lock, and reached out. Zane and Kaplan ended up going into business together later that year, making use of Zane’s father’s sheet metal business and expertise.

In 1972, Zane purchased the lock idea from Kaplan and, with $1,500, founded the Corporation. For the first few years, Kryptonite was managed out of the back of Zane’s Volkswagen van as he traveled the U.S. hocking his U-locks at bike shops, on college campuses, and to law enforcement. With little money for advertising, Zane staged a publicity stunt, locking up a bike in New York’s Lower East Side for a month. The resulting press helped launch the company into prominence.

Thermarest Sleeping Pad: 1971

Seattle aerospace giant Boeing laid off 50,000 people in 1971, and among the newly jobless were engineers Jim Lea and Neil Anderson. At that time, camping air mattresses were cold and prone to leaking, while closed-cell foam pads were bulky and uncomfortable on long expeditions. One day, when Lea was doing yard work, he noticed that the gardening cushion he was kneeling on expelled air as he shifted his weight and that the open-cell foam it was made from had memory. He and Anderson began working on a mattress prototype, sealing open-cell foam in an envelope of airtight fabric with an old sandwich maker, creating a bond that was leak free, and finally adding a valve. It was ’ first product.

Sorel Caribou: 1972

Sorel was the first boot brand to unite leather uppers, handcrafted vulcanized rubber shells, and removable felt liners for warmth and weather protection. The three materials combined to give this boot all the best characteristics of each—and were placed appropriately for maximum weather proofing and comfort. At the time, most winter boots were made from a single material, like leather, with uniform insulation. But not only was the design revolutionary, it was way ahead of its time: The remains one of the company’s most popular styles today.

Nalgene Plastic Waterbottle: 1972

The company of Rochester, New York, began making plastic pipette holders for lab work in 1959. Over the next decade, the company expanded to make a full line of plastic lab equipment. Around 1970, Nalgene President Marsh Hyman noticed that his bottles disappeared each weekend when the company’s scientists headed out to hike, camp, or fish. Hyman’s son was a boy scout, and when he forgot to buy enough canteens for the troop, he borrowed from his own stock of plastic bottles and sent them out on the trail with his troop. The scouts found the plastic bottles to be perfect for carrying water and powdered foods. Marsh, sensing opportunity, asked his company’s specialty department to start a broad publicity campaign to spread the word. The rest is history.

Hummingbird Modular Ice Axe: 1972

In the world of ice climbing, brothers Jeff and Greg Lowe were visionaries. After a two-year stint in the special forces, Greg returned home to Ogden, Colorado, in the early 1970s to nurse his fledgling manufacturing company, . Though Yvon Chouinard and others had already produced a curved pick ice tool—a modified mountaineering axe, and an improvement on the 90-degree-angled alpine axes previously in use—ice axes were still in their infancy.

In the winter of 1971-72, Greg Lowe let his backyard swimming pool freeze and he used it as his lab to redesign ice equipment. Among his many innovations was the Hummingbird, the first ice tool to feature interchangeable picks and a true curve that could reach around bulges and sink in. By the late 1970s the Lowe brothers were working with Italian manufacturer CAMP to produce the axes commercially, and Greg’s innovations were being put to use on cutting-edge ice climbs in the Canadian Rockies, Utah, and Colorado.

Sherpa Aluminum Snowshoes: 1972

After wooden snowshoes proved heavy and insufficient for winter mountaineering in Washington’s Cascades due to poor traction, Gene and Bill Prater developed an oval-shaped, aluminum-framed snowshoe with a neoprene deck and steel hinge rod binding. They released Sherpa snowshoes in 1972 to wide acclaim. Unfortunately, several years of high-turnover management and ineffective marketing plagued the company, which folded in 2002. Sherpa snowshoes are still traded secondhand, and widely regarded as some of the highest-quality snowshoes ever designed.

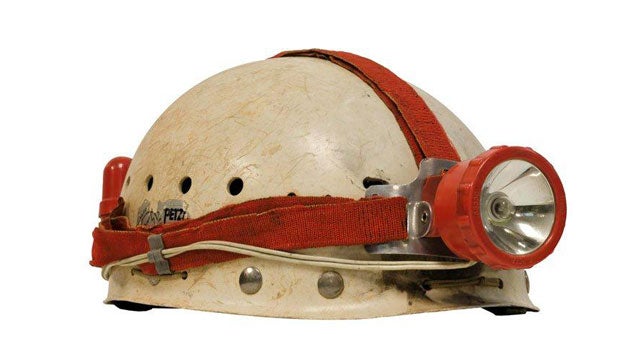

Petzl Headlamp: 1973

Fernand Petzl, an avid caver, set a depth record for cave descents in 1952, the same year Sir Edmund Hilary summited Everest. In his quest to help cavers be faster, lighter, and more efficient, put a headstrap on a light and took the battery pack off the waistbelt, mounting it on the headstrap as well. He made his first prototype from elastic cut from his wife’s bra.

Leki Makalu Adjustable Trekking Poles: 1974

“image”:”

Karl Lenhardt developed an expander dowel locking system that tightened and loosened with a twist. He used the technology in a sectioned tubular aluminum trekking pole that could be expanded for hiking, collapsed for storage, and adjusted in the field. In 1975, introduced the carbide pole tip, which gave trekkers better grip on rock and wore better mile after mile.

Bell Biker Cycling Helmet: 1975

After two years of prototyping, introduced the first bike helmet made from fully expanded polystyrene (EPS). The shock-absorbing cycling helmet was inspired by polystyrene foam motorcycle helmets, and replaced the leather hair net style of previous designs. Bell and other manufacturers were the primary promoters of bike helmets until the 1980s, when reports were published confirming that helmets are critical safety gear for cycling and significantly reduce head injury.

Bike helmets protect the head by acting as a shock absorber, the reports from the 1980s finally made clear. They reduce the rate at which the skull and brain are accelerated or decelerated by an impact. On impact, the expanded polystyrene liner is intended to crush, dissipating energy. A helmeted head makes impact with the ground six seconds after the helmet makes contact, significantly reducing the force placed on the skull itself.

Manufacturers also experimented with cork, balsa wood, and a silicone aluminum for building helmets, but none of these materials proved to be more effective than polystyrene.

Kodak Digital Camera: 1975

It took a year of piecing together electronics and camera parts in a back lab at ’s Elmgrove Plant in Rochester, New York, before the engineers and technicians at the Kodak Apparatus Division Research Lab had a Frankenstein collection of digital circuits that they called a portable electronic camera. The first digital camera used a lens from a bin of discarded Super 8 movie camera parts, and a portable digital cassette instrumentation recorder shoehorned onto the side. It took 23 seconds to record a digitized image to the cassette, and the image could only be viewed by removing the cassette from the camera and placing it in a custom playback device.

The technology advanced rapidly, which is probably why you don’t remember that custom playback machine, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that cameras began to reach a broad consumer base. After an aggressive marketing campaign in conjunction with Kinko’s and Microsoft, Kodak managed to make digital cameras ubiquitous.

Brooks EVA Midsole sneaker: 1975

Brooks was the first company to use spongy Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) in their running shoe insoles, which today is an industry standard. EVA is a closed-cell foam that is lightweight, provides cushioning, and absorbs shock. partnered with Monarch Rubber Company to develop this air bubble-filled polymer. It has become the go to material for cushioned footwear manufacturers, many of whom now combine it with other materials that don’t break down quite as quickly with regular use.

Hilleberg Keb Silicone-Coated Fabric Tent: 1975

The industry standard for tent fabrics was, for a long time, polyurethane-coated polyester. In 1975, tent designer and manufacturer Bo Hilleberg received a fabric sample from Belgian textile supplier Cotesa, which was testing out a different coating on standard tent fabric. They asked Hilleberg to try it out and see what he thought. Immediately, noticed that it didn’t tear. Because silicone wraps around, along, and through the fibers of a fabric and bonds so strongly, it adds elasticity to coated fabric, and increases its strength. Greater strength equals greater safety. In tents, the stronger the fabric, the better it is able to handle bad weather and hard use. The new silicone made fabric four times stronger but not any heavier, and it didn’t affect its waterproofness. Hilleberg’s Keb was the first commercial tent with silicone-coated fabrics, and a linked tent and fly that allowed the user to pitch both in one step.

Snow Lion Polarguard Mummy Sleeping Bag: 1976

Snow Lion’s synthetic backpacking mummy bag was the first high-performance sleeping bag. At that time, most synthetic bags were heavy and were prone to shifting insulation that left cold spots. The Snow Lion used continuous fiber filament insulation that kept warmth evenly distributed. And, to prevent cold air from sneaking in at the zipper, Snow lion added a patented draft-busting double zipper.

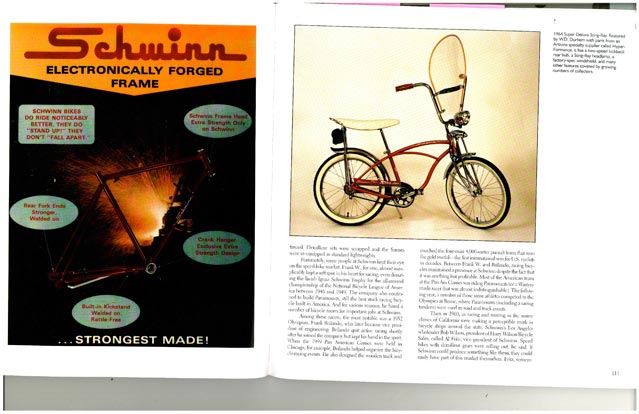

Schwinn Stingray BMX Bike: 1976

It was 1962 when designer Al Fritz learned of a new California youth trend: kids retrofitting their street bikes with knobby tires, hi-rise crossbar handlebars, and banana seats so that they could ride and race and jump motocross style. The trend inspired Schwinn to make the first commercially available tool for the job—the Stingray. It had a cantilever frame, 20-inch wheels, knobbier tires, a crossbar handlebar for strength, a banana seat, and coaster brakes. It was upgraded in ‘79 with a reinforced triangle frame, side pull caliper brakes, and a standard saddle. BMX racing fathered freestyle riding.

Early Winters Gore-Tex Rainwear: 1976

Bill and Vieve Gore launched in the basement of their home in Newark, Delaware, in 1958 to pursue their belief in the untapped potential of polytetrafluoroethylene, or PTFE. Gore’s first product was MULTI-TET Insulated Wire and Cable, used in defense applications and the burgeoning computer industry. It wasn’t until almost 20 years later that Gore sold its first fabric for outdoor use to the Early Winters catalog to be built into rainwear. Early Winters advertised its first Gore-Tex jacket as “possibly the most versatile piece of clothing you’ll ever wear.”

MSR Pit Zips: 1976

Durable, weatherproof outerwear got more comfortable with the incorporation of the first underarm vents that could be opened and closed. used them first in its rain jackets and parkas. Breathable but waterproof jackets hit the market the same year that MSR devised the pit zip, when most waterproof jackets were made of thick plastic that trapped in moisture and sweat. Adding pit zips allowed weatherproof shells to vent from a particularly moist area that was also at low likelihood of getting wet from the outside.

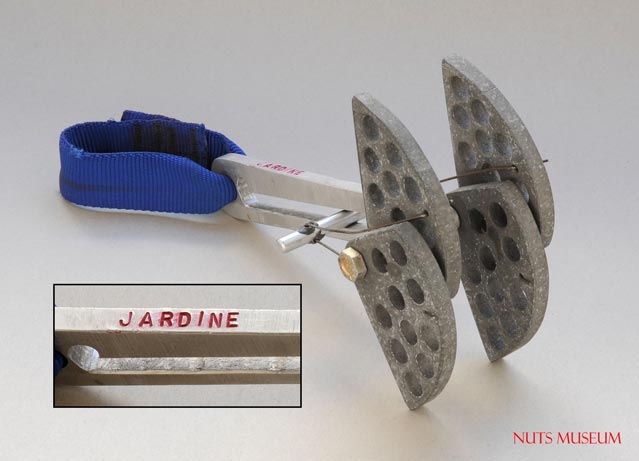

Wild Country Friends: 1978

Aeronautical engineer Ray Jardine was trying to climb the hardest single pitch trad route in the world, Yosemite’s The Phoenix (5.13a). It was strenuous and difficult to protect with nuts and chocks. Using his own considerable mechanical knowledge and information gleaned from a dinner meeting with climbing’s most accomplished inventor, , Jardine designed and commercialized the first spring-loaded camming devices. The device drew on the principle that a curved lobe could intercept the rock at a constant angle, all of which was described in Lowe’s 1973 application for a cam precursor.

In 1978, Mark Vallance, working with Jardine, founded Wild Country and began selling Jardine’s cams, called “Friends.” Lowe felt that Jardine had violated the terms of their non-compete, non-disclosure agreement, and filed a suit against Wild Country that was settled out of court. Today, cams are an essential part of every climber’s rack.

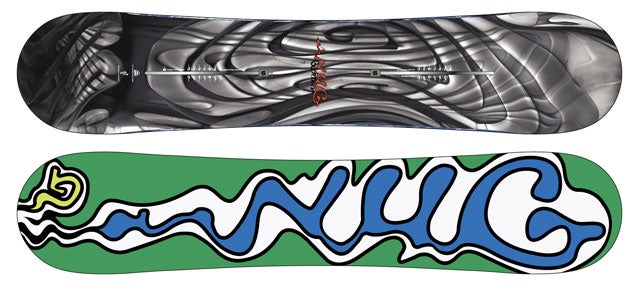

Burton Snowboard: 1977

Jake Carpenter modified the binding-free Snurfer into what he called the first snowboard. Carpenter’s snowboards were shaped out of a single plank of wood instead of two, and he attached rubber foot-strap bindings instead of a rope through the nose. Carpenter built his first snowboards by hand in his shop in Londonderry, Vermont. Now only could he not afford to outsource the manufacturing, but he couldn’t even afford proper ventilation equipment at the time—so he and his co-founder, east coast surfer and founder of Winterstick, Dimitrije Milovich, coated the boards in polyurethane while wearing a scuba mask.

Gary Fisher Mountain Bikes: 1979

Fisher and other riders started grafting moto parts—like thumbshift-operated derailleurs and motorcycle lever-operated drum brakes—onto cruiser bikes to ride dirt trails in Marin County, California. A pack of riders made bikes for themselves, but other riders were starting to ask various members of that crew to sell them a bike. In 1979, Gary Fisher and Charlie Kelly finally decided to capitalize on the popularity of their creation and started a bicycle company. They called it Mountain Bikes, naming a business and sport simultaneously.

Champion Jogbra: 1978

Hinda Miller, now a senator in Vermont, and Lisa Lindahl designed the first jog bra for women by sewing together two men’s jockstraps for cups, after Lisa’s husband paraded around wearing a jockstrap on his chest saying, “here’s your jockbra, ladies.” After trying out their creation, Hinda, Lisa, and costume designer Polly Smith drew up a business plan and sought funding. Hinda’s dad lent them $5,000, and they worked with a South Carolina manufacturer to make the first Jogbras. At first they distributed by mail order, eventually moving enough merchandise to convince sporting goods stores to stock their product—the trio decided that their new bra was equipment, not lingerie. Early prototypes now reside at the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

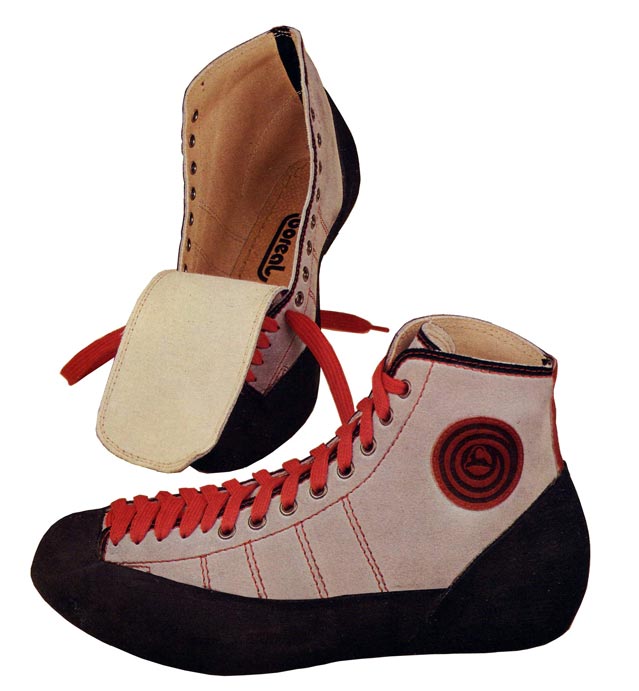

Boreal Firé Sticky Rubber Climbing Shoe: 1979

To a modern climber accustomed to sticky rubber shoes, the idea of climbing without high-friction footwear is almost unimaginable. Yet it wasn’t until 1979 that Boreal released the iconic Firé, and with it opened up a new world of technical climbing.

The idea for a sticky-soled shoe came from the Spanish Gallego brothers, who asked Boreal to develop a climbing shoe with better friction on rock than the hard plastic-soled shoes that were standard issue at the time. Jésus García Lopez, ’s founder, worked with engineers to develop a special rubber that could grip, and debuted it on the Firé, named for the reddish rock spires in Las Peñas de Riglos, Spain.

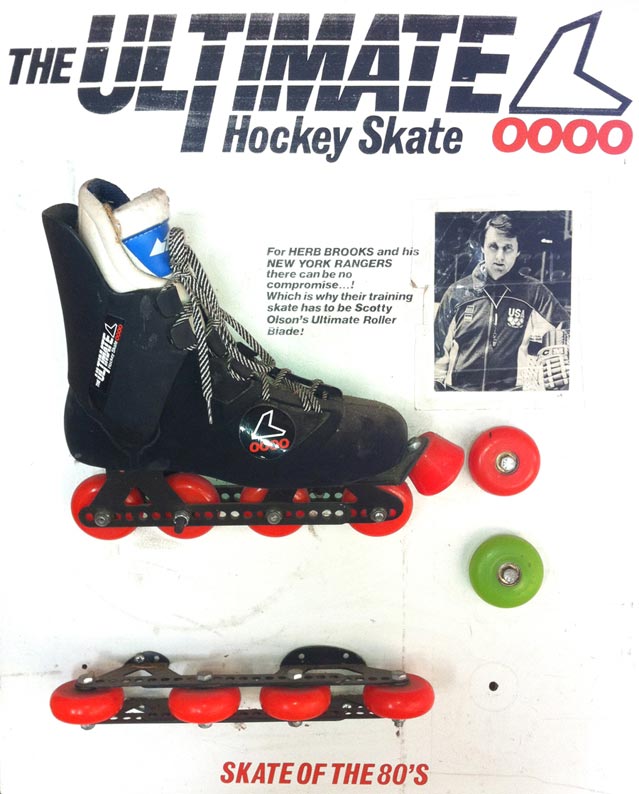

Rollerblades: 1980

Scott Olson and Brennan Olson, two hockey-playing brothers from Minnesota, were rummaging through a sporting goods store in 1980 when they discovered roller skates that had been modified. The special pair had all of its wheels in a row instead of at the four corners of a metal underfoot frame. In an effort to create a skate that would serve as a training tool in the offseason, the Olson’s began reworking the wheel placement. They played with bolting inline wheels to their ice hockey boots and adding rubber toe bumpers. Quite quickly, the first pair of rollerblades took shape in their shop. The popularity of quickly soared and it was included as one of nine sports in the first X-Games. Though the activity has lost steam in the United States since the ‘80s, the French still embrace it.

Eskimo Topolino Playboat: 1980

Prior to 1980, most whitewater kayaks were over 12 feet long. The design was effective for running rivers, but the boats were not particularly nimble. Holger Machatschek, together with Germany-based , developed the Topolino, which, at 7.2 feet long, allowed the paddler to introduce a whole new vocabulary of techniques and tricks. This new short boat paddling style, dubbed playboating, quickly developed into a popular subgenre of kayaking.

Malden Mills/Patagonia Fleece: 1981

Fledgling experimented with bunting and faux fur fabrics as synthetic alternatives to wool insulation—they wanted something durable that could dry fast. They collaborated with Malden Mills upholstery fabric and faux fur supplier, and together the two developed a circular knit fabric that comes off the knitting machine looking like a giant terry cloth tube sock. The fiber loops are then sheared at exactly the same height so that they hold each other up to create airspace that keeps the wearer warm.

Specialized Stumpjumper: 1981

tig-welded Stumpjumper, designed by Tim Neenan, was the first mass-produced mountain bike. Before the Stumpjumper, mountain bikes were being hand built, or around-town bikes were being individually modified to make them trail ready. The process was expensive and there was a long wait time for a custom bike. The Stumpjumper was mass-produced in Japan based on the design for a custom-made bike originally marketed by Tom Ritchey, Gary Fisher and Charles Kelly. It sold for $750, and had French touring parts (brakes and cranks), Japanese parts (hubs, shifters/derailleurs), motorcycle-sourced brake levers, and a BMX stem and pedals. Despite the steep price, especially for the early ‘80s, once the box arrived, the bike had to be built almost from scratch.

Gramicci G Short: 1981

Mike “Gramicci “ Graham gave the first G-Shorts to his climbing friends in “prepared for dye” white. They would then dye them at home with RIT and head for the nearest crag to serve as test models. The shorts had a diamond-shaped gusset in the crotch for freedom of movement and a hidden elastic waistband that expanded and contracted. Graham eliminated a zip fly because it was anything but comfortable against a rock face. He swapped it for a one-piece, one-hand adjustable plastic belt buckle that could be locked by pulling on the belt and released by tilting the buckle. After the thumbs up from his friends, started manufacturing the shorts and dyeing them in a small factory in Oxnard, California. He sold the finished pairs out of his van with the help of a small group of reps. Today, the shorts, which are still made, are known as the original G Short.

Polar Sport Tester PE 2000 Wireless Heart Rate Monitor: 1982

In 1975, while cross-country skiing near his home near Kemple, Finland, Seppo Säynäjäkangas had a chance encounter with an old friend who was working as a coach. It led to a discussion over how to accurately measure athletes’ heart rates during training. Just four years later filed its first patent for wireless heart rate measurement and, in 1982, launched the first ever wire-free wearable heart rate monitor.

Manhattan Portage Messenger Bag: 1983

In the early ‘80s, most carry bags were made of canvas or nylon, both of which broke down or wore out fast. John Peters, founder of , designed a trendy version of the durable 1950s utility lineman bags originally made by De Martini Globe Canvas Company. De Martini’s bags allowed lineman to carry their tools when they were climbing utility poles and kept them within easy reach. Peters replaced the stainless steel hardware of the Globe bags with lighter-weight plastic clips, the heavy canvas with durable Cordura, reflective stripes, and a tough-edge binding. The bags were light, durable, visible and much easier to carry on a bike.

Leatherman Multitool: 1983

During months of dirtbagging through Europe, the Middle East, and Asia on his honeymoon in a $300 Fiat that broke down a lot, Tim wished he had pliers on his scout knife. Back home, he made both cardboard and metal prototypes, and tried unsuccessfully to sell the idea to the United States Military, AT&T, and others. Finally, he got an appointment with Early Winters, a catalog merchant, and they agreed to purchase the tool if he simplified it to lower the price. Leatherman removed the extra vice grip and the pliers, which he later added to higher-end models. Cabelas bought the first 3000 Leathermans while Early Winters was still undecided. Between the two retailers, Leatherman sold 30,000 multitools its first year.

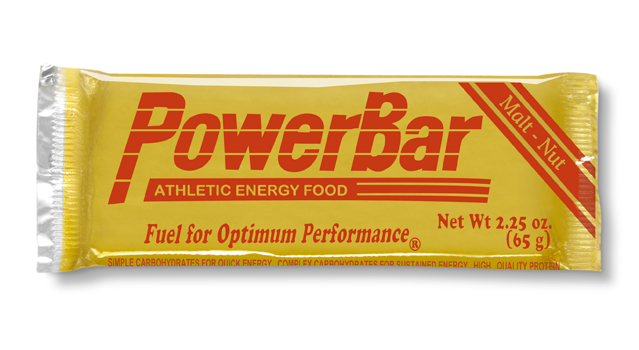

Powerbar: 1983

Brian Maxwell, an Olympic marathon runner, hit the wall 21 miles into a race and couldn’t finish. After this event, he started searching for an energy supplement that endurance athletes could eat before and even during events. When he couldn’t find something suitable, he and his wife-to-be, nutritionist Jennifer Biddulph, started working on snack bar recipes that would taste good and be easy to digest. That’s how the Powerbar came to be.

To start, Maxwell and Biddulph mixed and sold their creation out of their Berkeley, California, kitchen. Eventually they were able to convince a local candy maker to let them use the factory machinery on the nights and weekends to make .

With a large supply built up, the duo attended every running race in California and many others outside of the state in order to hand out free, unlabelled, unwrapped Powerbars to athletes—with a comment sheet attached. Maxwell bought a van and stenciled #7 on it so that it appeared that he had a fleet of Powerbar vans on the race circuit, even though this was his only one. Leveraging his own reputation as an elite marathoner, he convinced athletes to try his samples. Popularity soared after an endorsement from Greg LeMond, who used Powerbars during a Tour de France victory.

Vasque Sundowner: 1984

These leather backpacking boots were one of the first to use cement—not stitching—to attach the sole to the leather upper. The result was a lighter leather boot with more flexibility in the forefoot that didn’t compromise support or stability. The was also the first seamless, single-piece leather upper boot. And it’s still made today.

Latok Diamond Softshell Pullover: 1984

Jeff Lowe wore a stretch cross-country ski top and Nordic knickers on multiple climbing first ascents in the United States and abroad because Nordic ski garments gave him better flexibility than he could get from traditional climbing clothes. His partners, Mike Weis, Duncan Ferguson, and Bob Culp, were trying to build the perfect climbing suit at the same time—a full-coverage, one-piece body suit from woven synthetic fleece laminated to an exterior of stretch-knit Lycra. The tightly knit outer shell was almost as smooth as a woven fabric and shed snow before it had time to melt from contact with the climber, except in those areas where the contact was continuous over a long period of time. Lowe was working on his own version—a one-piece cross-country ski suit made from modified wind-proofed polypro underwear. , with the help of Swiss fabric innovator , developed a hybrid of the two projects. The completed garment had an outer layer of tightly-knit nylon/Lycra backed with a thin, breathable, but highly wind and water-resistant, coating, laminated to a thin layer of polyester insulation laminated to a stretchy tricot lining.

Advil: 1984

Ibuprofen was released in 1974. On May 18, 1984, Wyeth (now Pfizer) received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its ibuprofen analgesic , the first new non-prescription pain reliever in the United States in 29 years. Now, it’s the number one selling over-the-counter analgesic brand in the world with over 100 billion Advil tablets sold in the past 25 years alone. It’s the go-to anti-inflammatory for nearly every athlete, from weekend warriors to enthusiasts and beyond. None other than Jon Bon Jovi now personally endorses it.

Look PP 65 Clipless Pedal: 1984

engineers leveraged the company’s history in ski binding to create the first clipless pedal. The releasable design allowed cyclists to transfer power directly and efficiently to the bike through their pedals by locking the rider’s foot to the pedal with a cleat that clips in and out of a spring-loaded base plate. Thus, a rider can both push down and pull up on the pedal, spreading the load across more major muscle groups so that no one group fatigues quickly. Using lessons learned from developing releasable ski bindings, LOOK designed the cleat to release at any speed when the cyclist moves his heel a few degrees in or out.

MSR Whisperlite Stove: 1984

In 1973, when dehydration was identified as the main cause of Acute Mountain Sickness, developed the world’s first remote-burner stove to help mountaineers combat high-altitude malaise. The Model 9, designed to efficiently melt snow for drinking water at high altitude, became, almost immediately after its release, essential equipment for mountaineers around the world. But it was loud. To maintain the solitude of the outdoor experience, MSR developed the Whisperlite backpacking stove in 1984 to operate without the roaring hiss of the Model 9.

ABS Pack: 1985

Bavarian hunter Josef Hohenester got avalanched twice while carrying a deer back from the mountains. The deer provided flotation, preventing Hohenester from being buried in the snow. Peter Aschauer bought the idea from Hohenester and created the first device. It was worn like a backpack, had a cable pull, and weighed 8.8 pounds without a pack. The nylon-weave poly-lined balloon bag, inflated with 150 liters of nitrogen, was the first airbag avalanche protection.

Plastech Welded-Seam Dry Bag: 1986

Dry bags date all the way back to the Vietnam War—at the time, the United States government issued rubber-coated bags that were cemented at the seams. But Plastech, later acquired by and called SealLine, was the first to weld its closure straps, which never pulled out and which provided a drier seal; to weld fail-free round bottoms in dry bags, which made the bags easier to load in a kayak hatch; and to eliminate square corners, which tended to become abraded and leak.

The Helmet Cam: 1987

Mountain biker Mark Schulze wanted to capture the feel of riding a mountain bike for his film, . To accomplish this, Schulze stripped-down a red motorcycle helmet and jury-rigged a mounting for the first consumer color video chip camera. A cable ran from the camera to a padded backpack that contained a Panasonic VHS portable video recorder and a DC-lead-acid battery for power. The rig was heavy, unwieldy, and hot, but it brought a whole new perspective to action sports videos.

Schulze continued to work on his helmet cam design and eventually managed to pare the entire contraption down to a feathery 12 pounds. Asked why he never bothered to patent or commercialize his design, Schulze replied that he was too focused on shooting the best mountain bike videos. To this day Schulze continues to produce videos as the founder of New & Unique Videos.

Schultze married his wife, Patricia Mooney, on a mountain bike and the couple filmed their wedding with the original helmet cam.

Teva Hurricane: 1988

It was sometime in 1984 when young Grand Canyon river guide Mark Thatcher decided he wanted a sandal that would drain and have a hiking boot-like grip in and out of the water. Sneakers were too heavy when wet and would take days to dry, and flip flops slid off his feet too easily, so Thatcher decided to create something for himself. He fashioned a from rubber with nylon ankle strapping to make the first sport sandal. His (very specific) patent: A sandal with an elongated sole configured to the profile of a human footprint with a toe end and a heel end that employs a toe strap connected at two anchor points to grip the forward part of the user’s foot and a heel strap connected at two anchor points to grip the ankle of the user’s foot with a lateral strap connected between the toe strap and the heel strap which is located on the outside of the sole and parallel to its surface so it is operable to stabilize the other straps and to maintain constant tension in the individual straps as the sole flexes, with the toe and heel straps being infinitely adjustable so the wearer can cinch the sandal to his foot by adjusting said straps in a manner that it will not be dislodged during rigorous activity.

Latok Tuber Tubular Belay Device: 1982

In the early 1980s got the idea to create a single device that would be equally effective for belaying and rappelling. His goal was to eliminate the disadvantages of a sticht belay plate, which continually jammed up during rappels, and a Figure 8 rappel device, which twisted and kinked his rope. His designed a metal tube with a metal cable attachment point, which was not only more effective than its predecessors but considerably lighter as well. Lowe never patented the design, and as a result the tubular belay device design is still made by numerous manufacturers.

MSR Isopropane Fuel: 1989

ISOPRO fuel, a mix of isobutane and propane, revolutionized canister fuel because the fuels in the mix have different boiling points, which maintains the uniform vapor pressure inside the canister as it is drained or the temperature changes. The first canisters of Isopro fuel looked like hairspray.

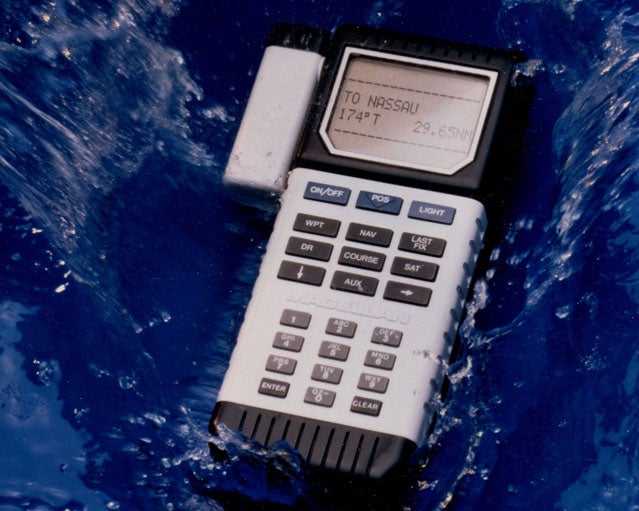

Handheld GPS Magellan: 1989

Almost immediately after GPS technology was developed by the United States Military, Ed Tuck, a pilot at time, became interesting in adopting it for his own use. Tuck had a friend who lived on the West Coast, but there were no navigation systems in the area, making it hard for Tuck to fly in to visit. During the years that Tuck experimented with GPS he co-founded , which would go on to become one of the most recognized brands associated with the technology.

Tuck’s first handheld GPS units had to be tested in the middle of the night as there were few satellites in orbit and the device needed access to three to four at a time to get a decent reading. Product managers would skulk around Los Angeles parks, where they were routinely questioned by police, with their handheld units to try and find satellites.

The first consumer-ready product was targeted to mariners, who, once they were 20 miles from shore, had only celestial navigation to get them home. In 1992, in conjunction with Jim Whittaker from REI, Magellan began targeting GPS to people who worked and played outdoors. Today, Magellan units read off 28 or more satellites orbiting the earth.

Rock Shox RS1: 1989

In 1987, Paul Turner, a motocross factory mechanic, showed a full suspension bike at the Interbike tradeshow with the help of bicycle parts manufacturer Keith Bontrager. No one was interested; the crowds passed him by. But just two years later Turner and his wife, Christi, were manufacturing suspension forks in their garage with parts bought from Steve Simons. Simons, who had developed suspension for motorcycles, soon partnered with Turner in .

Greg Herbold became the first world champion in biking on one of the first suspension forks made by Rock Shox for mountain bikes. In August of that year the company manufactured its first 100 suspension forks, the RS-1.

Camelbak Hydration Pack: 1989

Paramedic Michael Eidson wanted to push past his limits on a sweltering hot Texas century ride, the Hotter-N-Hell 100. His biggest challenge was figuring out how to carry enough water with him. The solution: Eidson rigged a hydration system using an IV bag with a surgical tubing straw housed in a tube sock sewn to his jersey to hold the bag. The first commercial , based on Eidson’s makeshift prototype, was a little more presentable: It was a purple pouch with Velcro closures and a tube coming out. The rubber cork cap kept the water from leaking out, but the user had to pull it open each time he or she wanted to take a sip.

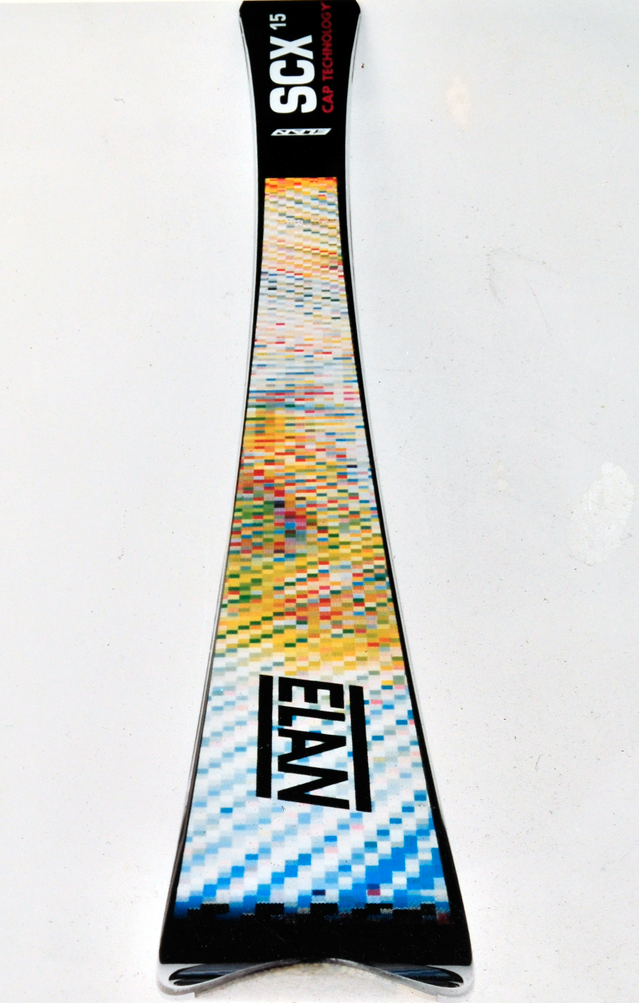

Elan Knissel SCX Shaped Ski: 1991

In Slovenia, Elan had a unique ski-building mold with hundreds of tiny screws that allowed designers great variation in determining ski sidecut. ’s engineers were using this mold when experimenting with designs for a faster race ski, working with the idea of introducing sidecut that more closely mimicked the turning radius in a Giant Slalom racecourse, when they came up with what would become the SCX.

The first prototype, called the Light Speed parabolic, was sent to “crazy Americans” in Elan’s United States offices for testing. Mike Adams, Elan president, took the protos to ski area personnel for tryouts instead of simply putting them on elite athletes, a tactic many other companies have used to generate interest. Instructors instantly saw how easy it would be to teach new skiers how to turn at slow speeds on these radically shaped skis.

But it wasn’t just beginners who were seeing results. At Vermont’s Sugarbush Resort individuals who previously weren’t on the map won races on shaped skis. People were performing so well with Elan’s new product, that the shaped ski was being called “the cheater ski.”

Elan created grassroots demand, initially selling just to rental shops. The company hit record sales, and it was one of the first times that skis were mentioned in mainstream press.

Smartwool Merino Socks: 1994

Clothing manufacturers learned quickly that wool was the best fiber to keep skiers’ feet comfortable on the slopes, but it shrank and was itchy. was able to discover a process to make wool fiber soft and easy to care for while also identifying the properties of wool, like staple fiber, that, when modified, further reduced itch. Smartwool introduced merino to the market in its socks. Since then, they’ve sold more than 70 million pairs. Now, merino is not only used for socks, but for clothing from base layer to outerwear by a number of apparel companies around the world.

Black Diamond Hotwire Wiregate Carabiner: 1995

On top of being one of backcountry skiing’s most accomplished athletes, Andrew McLean has contributed immensely to climbing gear technology. New on the job at in the mid-90s, he drew knowledge from his experience as a sailor, where wire clips were standard equipment, and proposed a similar design for climbing carabiners. Despite initial resistance within the company—the new design was a radical step from standard gate ‘biners—McClean managed to prove that his design was not only lighter and easier to produce, but also better resisted opening upon impact with rock. There was another advantage too: wiregates didn’t freeze in cold, wet conditions, making them the obvious choice for ice climbers.

GoLite Breeze Pack: 1998

Tired of hauling heavy, overbuilt gear up and down mountains, long distance hikers Demetri and Kim Coupounas founded outdoor gear manufacturer GoLite. In their first year the couple introduced 12 ultralight products that sparked an industry-wide shift toward lighter gear in the ensuing decade. The company’s first pack, the Breeze, had no hip belt or framesheet, and was the first to use uber-strong and radically lightweight Dyneema. The company was also the first to market an ultralight wind shell. ’s hooded Ether wind shirt and hoodless Wisp wind shirt both weighed in at less than three ounces.

Salomon 1080 Twin Tip: 1998

Racer Mike Douglas and his teammates would hit the snowboard park and try to do tricks on skis on their days off from racing moguls. In 1997, Douglas and Steve Fearing put together Air Carving, a promotional video to convince ski executives to build a park and pipe ski. Eight major manufacturers refused them before said yes.

Isis Women-Specific Technical Apparel: 1998

Vermonters Poppy Gall and Caroline Cooke spent their lift rides at Stowe complaining about their outerwear. It was too long, too baggy, and made for men. Over après ski beers one day, they decided to do something about it. They sketched the first Isis garments on the back of a napkin. Isis’ Split P shell pants had a front-to-back zipper hidden in the crotch seam so a woman could relieve herself in cold weather without removing her climbing harness. It complemented base layer bottoms with the same feature. But the features weren’t just functional; they were also cosmetic. jackets and pants were cut to flatter a female shape: contoured waists, shorter rises, and longer legs were standard.

Petzl Tikka Headlamp: 2000

Looking to extend the life of their batteries for underground exploration, a number of spelunkers modified their headlamps to use red, green and blue energy-saving LEDs (initially, only colored LEDs were made—no white bulbs). When new ultracompact white LEDs became available, caver engineers at went to work. The original Tikka headlamp used the first white LEDs. It was 8.75 lumens, ran on three AAA batteries that powered three LED bulbs, and weighed far less than any other headlamps available at the time.

Since the first Tikka, bulb color has whitened and brightened (the first LEDs had a bluish glow), and bulbs have become more efficient. The tiny LED e-Lite now has 28 lumens and runs on two watch batteries.

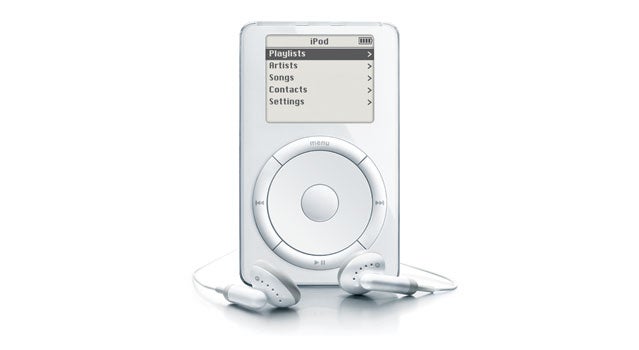

Apple iPod: 2001

We all know the story of the iPod, the first device to put 1,000 songs in your pocket. In less than a decade, Apple sold more than 275 million iPods in a variety of iterations and more than 10 billion songs through its iTunes store. This device let runners, cyclists, gym rats, and athletes of all caliber train with music, and saved them from the weight and awkwardness of tape players and portable CD players. The iPod gave outdoor enthusiasts access to more music than ever before in a personal player.

Volant Spatula Rockered Ski: 2001

was trying to create better powder and freeride skis when Volant athlete Shane McConkey handed Peter Turner, Volant executive, a pair of the company’s Chub skis. McConkey had bent the skis into a reverse camber shape, like a waterski. He followed up with a picture of pintail surfboards and a note saying that he wanted a ski that was wider underfoot and reverse cambered. “Powder is like water … fluid,” McConkey explained. “Look at everything people use in water: the shape is wider in the middle, and reverse camber.” During developing, the ski was called the Shape Shifter and then the Barrel before McConkie named it the Spatula—because skiing it was like smearing butter on toast.

Gary Fisher 29er: 2001

Though historically bicycles have had many different sized wheels, a collaboration between and WTB’s Mark Slate and Steve Potts brought the name “” to life, and the first mass-produced 29-inch wheel mountain bikes to market. Fisher was riding Pearl Pass, Colorado, sometime in the 1980s when he encountered huge rock obstacles in the trail and reportedly said, “We’re going to need bigger wheels to get over these things.” Independent manufacturers made 29ers before Fischer, including Wes Williams (Willits Bikes, 1988), and Geoff Apps (Cleland Cycles, 1981), but nobody else is credited with making the term go global.

Jetboil Personal Cooking System: 2004

Frustrated with heavy vacuum bottles and clunky stoves, Jetboil founders Dwight Aspinwall and Perry Dowsi set out to make outdoor cooking easier. They discovered that the secret to a fast and friendly design was in increasing heat transfer efficiency. They’d hike in about a mile on the Wilderness Trail in Lincoln, New Hampshire, with their prototypes—just far enough to avoid the park rangers—and set up a table with hot drinks and snacks to hook hikers. Armed with clipboards, non-disclosure agreements and questionnaires, the pair would lure test subjects in for feedback on their designs. Upon hearing their pitch, the first subject they approached looked them straight in the eye and said, “You know, I come up here to get away from guys like you.” After they changed their pitch from “Would you like to participate in a product survey,” to “We’re trying to invent a new way of cooking; would you be willing to help us out,” they brought in some quality feedback that led to the creation of the .

Vibram Five Fingers: 2006

Italian industrial designer , an earthy guy who loves the mountains and hates chunky boots, had an idea for a thin-soled shoe with individual toes. In trying to use his body in a more natural way, he hiked and climbed barefoot, but he would break his toenails and inflict all sorts of damage, which is why he created what would eventually become Five Fingers. (Fliri’s first models were five-toe fashion shoes. He also envisioned creating an individual toe shoe for water use.)

When Vibram USA was given the right to market and distribute the product in July of 2005, it shifted Five Fingers to a performance product category focused on fitness and running enthusiasts. Vibram USA’s Tony Post saw the benefits of barefoot running and individual toes when he started training in Five Fingers after knee surgery, and soon found he couldn’t run in anything else.

The shoe launched at the 2006 Boston Marathon on the feet of Born To Run’s Ted McDonald and, within a few weeks, the Wall Street Journal was writing about the new phenomenon. Vibram USA did 90 percent of its sales direct to consumers at first. In 2007, magazine named one of the best health inventions of the year because barefoot running has been shown to give athletes stronger and healthier feet and legs that are less prone to injury.

Spot Personal Locator Beacon: 2007