BACKPACKING HAS hauled itself into the new millennium quite nicely, thank you, so let’s try to put the memory of days spent sweating under awkward external-frame packs or—worse—supportless internal-frame packs behind us, permanently. Hell, if they can make freeze-dried shrimp Creole taste like, well, shrimp Creole and not like crustacean-flavored oatmeal, then they can make packs that suit our space needs without knocking us about and crushing a few disks in the process. Put simply, with the new generation of close-fitting, load-mastering packs, you no longer have to martyr your body in order to free your spirit in the wilderness.

TAKE THE WEIGHT OFF

our pick of the finest in bombproof backpacks from The North Face, Arc’Teryx, Lafuma, Marmot, Osprey, Gregory, Kelty, Lowe Alpine, and Dana Design. INSIDE: The coolest backcountry toys and amusing accessories by Colorado Boomerangs, iBocce.com, Wham-O, A.A. Knopf, and the World Footbag Association.

That is, if you have the right pack for the job. Buy one too big and you’ll cram it full of heavy gear you don’t need. Buy one too small, and you’ll end up lashing stuff all over the outside, overloading the suspension and screwing up your balance. As a guide: Packs in the 4,000-cubic-inch range do nicely for three-day weekends or longer trips in warm weather; packs that are 5,000 cubic inches and bigger are suitable for more epic expeditions. Alpinists and skiers (or bushwhackers, for that matter) need flexible packs that move with the body, which means a minimal frame—just a pair of stays, really. Heavier loads require more rigidity so the frame can transfer most of the load to the hips, where it belongs. For big trips, look for HDPE (high-density polyethylene) framesheets attached to the stays, and possibly a pair of load-transfer rods as well.

We’ve done some of the heavy lifting for you by testing nine standout packs in the 3,000- to 6,000-cubic-inch range. But with backpacks, fit is perhaps more important than quality, so find a shop that’s willing to spend two hours, not two minutes, selling you one. And then get out of town.

Light and Fast

The North Face Patrol l $200 l 2,990 cubic inches l

Marching—and skiing—to the beat of a different drummer, the Patrol (bottom) employs an unusual frame arrangement: two carbon-fiber stays arrayed in an X, resembling the suspension of a 40-year-old Swiss rucksack. What this design loses in vertical flexibility (compared with parallel or V-stays) it gains in strength. It’s simply impossible to overload the Patrol’s 2,990-cubic-inch bag; the frame, well-padded back panel, and harness—which adjusts for torso length—just soak it up. Surprisingly, the Patrol flexes effortlessly during torso-twisting activities such as skiing or snowboarding. Lift a hip while stepping up onto a boulder, though, and that crossed frame forces the pack to shift in the wrong direction (although loosening the side straps on the belt helps). Befitting its niche, the 4-pound, 13-ounce Patrol sports a removable snowboard, ski, and shovel pocket, an inside sleeve for a hydration bladder, and a side zipper for fast access to a shell or GPS.

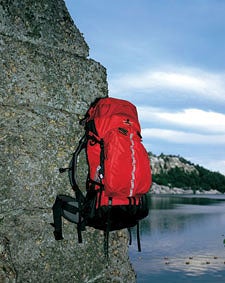

Arc’Teryx Khamsin 62 l $260 l 4,030 c.i.

At a gossamer 4 pounds, the Khamsin (upper left) is the guerrilla raider of the packs we tested, bred for light and fast skirmishes rather than protracted sieges. An abbreviated HDPE framesheet, with a central aluminum stay and two wands arrayed in a Y, handles loads up to 45 pounds or so, while three small back pads provide more comfort than we believed possible. The minimalist foundation means there’s little shape control—stuff a barrel-shaped load inside and the pack takes on the shape of a barrel, rolling side to side like a drunken sailor playing piggyback. But pack carefully and it’ll fasten itself to your trunk on even the most vertiginous route. Unlike some other pared-down packs, the Khamsin doesn’t scrimp on features: There’s a removable top pocket/fanny pack, interchangeable small, medium, and large hipbelts, a side-access zipper, dual ice-ax loops, and a crampon patch. Perhaps the highest-quality pack we tested, the Khamsin is sewn in Canada with fanatical attention to detail.

Lafuma Extreme 72 l $190 l 4,400 c.i. l

The Extreme (upper right) comes so loaded with specialized alpinist features, you can feel hypoxia coming on just looking at it. In addition to reinforced ice-ax holders and double-duty ski/pole sleeves, there’s a probe-pole pocket inside, numerous daisy chains on the back, a patented stretch helmet pouch, and a pocket for a camera to record your summit triumph. There’s even (pardon the translation from the French) a “pocket for papers”—presumably of no help if you get tagged on the wrong side of the Afghan border. Granted, all of the above would be mere window dressing if the Extreme didn’t handle well on steep, off-trail routes, which it does in style. While the single-piece, upside-down-U aluminum frame doesn’t promise much flexibility, it’s narrow enough that it doesn’t hinder hip movement. Just as important, it twists with your torso to keep moderate (40- to 50-pound) loads glued tight in situations where losing your balance would be the end of you. None of the high-elevation features, of course, prevents this bargain-priced pack from being a comfortable companion on more mundane routes; just try to look extreme when you run into someone on the trail.

Short Excursions

Marmot Muir l $250 l 4,500 c.i. l

Whether you’re a backpacker, cross-country skier, or mountaineer, this might be the best long-weekend pack around. The Muir’s frame—a large HDPE panel with two aluminum stays in a V—achieves a near-perfect balance of flexibility and load-carrying rigidity that works equally well whether you’re scrambling down trails or up couloirs. Nicely curved shoulder straps and a dual-density hipbelt ally for comfort with a broad back panel (which, made from closed-cell foam, is a bit sweaty in hot weather, even with the air channels). Despite the fact that the Muir (below right) has separate sleeping-bag access and five exterior pockets to keep a three- or four-day load organized, it’s narrow enough not to interfere with skiing. The frame stays remove in seconds for personalized rebending; however, the shoulder harness is not adjustable for torso length, so make sure you get the right size pack (the hipbelt can be moved up and down, but that’s not the optimum way to compensate).

Osprey Crescent 75 l $390 l 4,500 c.i.

If other packs balance well enough for climbing, with the Crescent (below left) you could walk tightropes—while juggling. This fine-tuning is achieved through two radically curved exterior fiberglass rods, which cinch the load tight to your back and up and over your shoulders, seemingly without a millimeter of excess play. Combine that with a remarkably flexible twin-stay/framesheet combination, and this pack does just what you tell it to. There’s room inside the 4,500-cubic-inch bag for four or five days’ worth of stuff, yet it’s narrow enough not to interfere while you’re swinging an ice ax. On the trail, the 6-pound, 5-ounce Crescent is comfortable with loads up to about 40 pounds. Beyond that, the hipbelt gets increasingly uncomfortable because it lacks an adjustment for cant—it squeezes your hips more than it cradles them. Nice touch: The dual zippered pockets, each of which easily holds a one-pound bag of M&Ms, are reachable while walking. Another boon: It’s handcrafted in Colorado.

Gregory Palisade l $285 l 4,700 c.i. l Put the Palisade (middle) next to a 20-year-old Gregory Shasta and you can hardly tell them apart visually. But don’t assume that the company that revolutionized backpacking has gone retro. It’s simply taken the parallel-stay frame, tall, narrow pack bag, and widely adjustable harness of their original design, and refined them with updated features and materials. The result is—still—one of the best-fitting packs in the world for all-around backpacking duty. The addition of a reinforcing HDPE framesheet joining the tops of the aluminum stays means the 7-pound, 3-ounce Palisade can easily control loads of 55 pounds or more while retaining most of its ancestor’s flexibility. The shoulder harness adjusts automatically to fit the slope of your shoulders, relieving pressure points, and the grippy fabric on the lumbar pad (a direct carryover from the Shasta) locks the pack to the small of your back. Best of all is the Palisade’s $290 price tag—an increase of just $60 in two decades.

Expedition Strength

Kelty Bigfoot 5200 l $290 l 5,200 c.i. l

After 20 years of internal-frame progress, why did Kelty revert to a semi-external frame for the Bigfoot (top left)? Well, because this frame/harness module can be clipped to any of three pack bags, in 2,300-, 4,300-, and 5,200-cubic-inch sizes. So instead of purchasing separate packs for different outings, you just buy another bag, saving money and closet space (the 4,300-cubic-inch Yeti bag sells separately for $125, the 2,300-cubic-inch Roswell for just $80). The frame incorporates a U-shaped aluminum stay and an HDPE sheet, plus a central fiberglass rod that clips into the pack—which has its own internal hoop stiffener that transfers weight to the hipbelt. (If you think it’s hard to visualize, try disassembling it without instructions.) The result is a multipack system and a frame that mates so closely with the bags that it would be misleading to call it external. It competently handles 45-pound loads in the largest pack; with a weekend load in the midsize bag you hardly know it’s there; and, well, it’s arguably overkill for the smallest, but you could strap on heavy alpine skis without overloading it. With all that structure, you wouldn’t think there would be much flex, but the Bigfoot follows your movements surprisingly well in moderate terrain. The frame does keep the pack bag a bit far from your back, however, so don’t be surprised if it sways when you push it hard.

Lowe Contour Classic l $180 l 5,200 c.i.

Check the specs of the Contour Classic (right) and you’ll find a healthy list of standard features. Check the price tag, and you’ll realize that what you’ve really found is the blue-light special of the backpack world. For 180 bucks Lowe gives you a dual-density shoulder harness and hipbelt, twin aluminum stays that pop out for rebending, and a big, 5,500-cubic-inch bag with a zip-out interior divider. The harness adjusts in a jiffy for torso length, and the “air-cooled” back pad really works—we know, because we tried it on a 90-degree Arizona day. With no framesheet to stiffen the stays, the Contour quickly runs out of load capacity above 40 pounds or so, but the upside is its supreme flexibility for ski touring or climbing. The bag’s excellent compression system means that the load stays tight through any sort of gymnastics you can think up.

Dana Terraplane LTW l $439 l 5,800 c.i.

LTW, that is, “lightweight,” might seem an odd suffix to hang on a 6-pound, 9-ounce pack, but the LTW (middle) is a full pound lighter than the regular Terraplane. And when you’re dealing with the kinds of loads this 5,800-cubic-inch monster can handle, every bit helps. The Terraplane is the pack of choice when your planned route requires you to tape several topo maps end to end. It’s unsurpassed at making a normal backpacking load feel pleasant and an expedition-size load feel almost pleasant. The secret is in the frame, a multitasked trusswork comprising a central aluminum stay, a large HDPE framesheet, and twin carbon-fiber wands that tie the bulk of the load to the optimum balance point at the sides of the hipbelt. And that well-padded, contoured hipbelt is the best in the business at cupping your hips rather than squeezing them. Admittedly, there’s not a lot of flexibility in the system—the Dana is better trudging up trails than bushwhacking—but it remains the standard for load-hauling prowess.

WHERE TO FIND IT:

Arc’Teryx 800-985-6681, ; Dana Design 888-357-3262, ; Gregory 800-477-3420, ; Kelty 800-423-2320, ; Lafuma 303-527-1460, ; Lowe Alpine 800-366-0223, ; Marmot 707-544-4590, ; Osprey 970-564-5900, ; The North Face 800-535-3331,

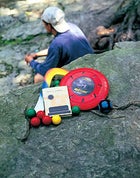

Playing Around

Climbing at Joshua Tree, windsurfing the Gorge, fly-fishing the Yellowstone—you know what you’re there to do. But let’s face it, when the crag’s wet, the wind ain’t blowin’, and you can’t set a hook to save your life, the great outdoors can be duller than C-SPAN on mute. Fortunately the solution is simple: Next time you’re sitting around camp crushing beer cans against your forehead to pass the time, try whipping out one of these lightweight and compact backpackable toys. They might not be as much fun as recreational hallucinogens, but they’re a lot easier to sneak past the rangers. —Tim Neville

Boomerang l $20 l Boomerangs aren’t just for thwacking baby ‘roos anymore. With the flick of a wrist, this high-performance “rang” from Colorado Boomerangs (800-357-2647; ), dubbed the Rainier, circles back at your noggin in a 35-yard arc. Handcrafted from Finnish birch, the 1.8-ounce Rainier includes instructions on how to wing the thing safely (the Labrador at the next tent is not a proper visual), and features a fuchsia-and-canary-yellow paint job that makes it easy to spot as it’s whirling toward your trachea.

Travel Bocce l $15 l Suggest a game of traditional bocce to anyone five decades shy of incontinence, and they’ll label you a pasty wanker. That’s because there’s an improved version of the Italian lawn-bowling game called, you guessed it, extreme bocce. The old game is played with 4-inch balls on meticulously groomed lawns, but the extreme approach relies on rocks, ruts, and dips in backcountry turf to make the game more challenging. This travel set from iBocce.com (925-855-9185; ) weighs 12 ounces and includes nine 1.5-inch solid-pine balls and a waterproof sack that fits easily in a trunk, pack, or boat for playtime anywhere. Now that’s Italian!

Max Flight Frisbee l $10 l Don’t let friends whip this baby around the campground unless you’re prepared for the consequences of dancing over the top of somebody’s tent to make the catch. The long-distance Max Flight Frisbee (877-469-4266; ) uses some of the go-far design tricks behind the user-unfriendly, hard-edged golf discs (Spot catches disc; Spot loses teeth). But the nine-inch-diameter Max Flight is easier to catch thanks to a rubber grip and thicker profile. Granted it’s not one of those distance-defying Aerobies that get caught in trees, but you can expect throws up to 350 feet.

SandMaster Footbag l $12 l Welcome to Stoner Fitness 101, Introduction to the Hack. Filled with sand instead of plastic beads, the 2.5-inch-diameter SandMaster, distributed by the World Footbag Association (800-878-8797; ), has a more forgiving feel than most bags. Add to it a 14-panel quilt of durable synthetic suede that gives it a rounder shape and reduces klutzy shanks, and the plum-size SandMaster becomes the bag of choice. Just don’t ever, ever apologize for a bad kick. It’s poor style, bro.

Sand and Foam, by Kahlil Gibran l $14 l Conversational lulls, begone! The early-20th-century Lebanese writer Kahlil Gibran inspires endless banter in Sand and Foamfrom A. A. Knopf (212-572-2600; ): 82 pages of outdoor koans in a book the size of a few slices of Spam. “So Bob, what do you think he means by, ‘Frogs may bellow louder than bulls, but they cannot drag the plough in the field nor turn the wheel of the winepress, and of their skins you cannot make shoes’?”

Books

A Breed Apart

Piece Like A River by Leif Enger

Piece Like A River by Leif Enger The Map That Changed the World by Simon Winchester

The Map That Changed the World by Simon Winchester

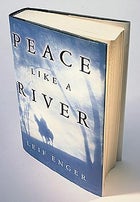

Peace Like a River

, by Leif Enger (Atlantic Monthly Press, $24).Some writers aspire to write a great Western. Leif Enger has written a great Midwestern, a debut novel that explores the limits of filial loyalty and inscribes the northern Great Plains on the reader’s bones. Eleven-year-old Reuben “Rube” Land narrates this early-1960s road trip, which begins when his older brother, Davy, shoots two town ne’er-do-wells and lams it on horseback into the pastured Minnesota night. Rube’s family hits the road after him, towing an Airstream trailer, not so much searching for outlaw Davy as hoping Davy will somehow find them. “[We’ll] simply go forth,” Rube’s father says, “like the children of Israel when they packed up and cameled out of Egypt.” The Lands lumber through Minnesota and North Dakota, the damp smell of fog and the 20-below chill so vivid that you’ll want to reach for a down parka. Enger’s people are tender hearted stoics, played not for humor but for something more raw—Garrison Keillor’s characters in the hands of Russell Banks. “We tiptoed through that town like a fat boy through a wolf pack,” says Rube when the Airstream sneaks past a phalanx of state troopers. A great line—and just a taste of what Enger, a reporter for Minnesota Public Radio, can do with the English language. —Bruce Barcott

Buffalo for the Broken Heart: Restoring Life to a Black Hills Ranch

, by Dan O’Brien (Random House, $23). A few years ago, Dan O’Brien (The Rites of Autumn: A Falconer’s Journey Across the American West) was a struggling, newly divorced rancher and environmentalist who hated cattle and yearned to restore the prairie ecosystem of his Broken Heart Ranch in South Dakota’s Black Hills. Then one day near the Badlands, he almost hit a bull buffalo—”stretched out in the sun like a two-thousand-pound tomcat”—with his pickup. The animal couldn’t have cared less: “He slowly raised the tiny, black hoof of his left rear foot, stretched his head out, and, as if the hoof were a delicate ballet slipper, scratched his neck below the long woolly goatee.” Like Saul on the road to Damascus, O’Brien saw his salvation, and soon acquired 13 orphaned calves, the nucleus of his new herd. His first year with the “bufflers,” as ranch hand Erney Hersman calls them, is a series of revelations. In the Great Plains version of Survivor, buffalo beat cattle cold: They don’t stand around fouling streams like “ungulate tourist[s]”; they don’t need hay in winter; they find their own grass; wind and snow barely affect them. Of course, it’s still a struggle, with endless miles of buffalo-proof fencing to put up and steep loans on the animals to repay, but O’Brien makes us see what the Great Plains were once and could be again: “an American Serengeti.”This is a bold, brave, beautifully written book that should be required reading for every cattleman and beef eater in America. —Caroline Fraser

The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology

, by Simon Winchester (HarperCollins, $26). This Dickensian tale of treachery involves—of all things—fossils, maps, and plagiarism, and Simon Winchester, author of The Professor and the Madman and other explorations of the British psyche, is the man to tell it. In 1793, an engineer named William Smith—hired to build a coal canal near Bath—noticed a world-shaking fact: that the rock underfoot was arranged in layers. To grasp the magnitude of this discovery, Winchester helps us inhabit the 18th-century, pre-Darwinian mind, which interpreted fossils as curiosities rather than the mineralized corpses of long-vanished species whose presence could lead miners straight to coal. Smith and other geologists recognized fossils for what they were, but Smith took the theory a step further, pointing out that rock strata “could be positively and invariably identified simply and solely by the fossils…found within it.” He set out to produce, in 1815, the first great geological map, an enormous, wondrously colored, scientific vision of England’s underworld. The map’s value—particularly to the Dick Cheneys and Exxons of the time—was such that plagiarists copied it, leaving its creator to spend a summer in debtors prison. As he later wrote, however, “the man might be imprisoned—but his discoveries could not be,” a decade later he finally won the renown he deserved. This richly illustrated book is a fascinating journey back to the dawn of the industrial revolution and the first glimmers of global warming. —C.F.

Fire,

by Sebastian Junger (W.W. Norton, $24). Nine years ago Sebastian Junger began a book on dangerous jobs, but shelved the project when his second chapter, about a swordfishing boat named theAndrea Gail, took on a life of its own as The Perfect Storm. Now, this nonfiction collection marries the remnants of the original book to Junger’s war correspondence, producing a record of the author’s transformation from wide-eyed adventure seeker to seasoned combat journalist. The title chapter, a plunge into Idaho’s 1992 Flicker Creek wildfire, offers up classic early Junger material: powerful men doing dangerous work and not whining. An attempt to write about war reporters turned Junger into one himself, and the book’s second half finds him filing magazine dispatches from Kosovo, Cyprus, and Sierra Leone, training his gifted descriptive eye on the dangerous work of destruction, death, misery, and survival. The turn from adventure jobs to wartime atrocities can be jarring, but Junger’s reporting is strong enough that you can’t close Fire without the feeling that there’s a great book about war in here waiting to be realized. In the final piece, Junger steps out of a medic tent, unable to stomach the agony. Then, driven by duty, he goes back inside. “This is the war too, and you have to look straight at it,” he tells himself. “You have to look straight at all of it or you have no business being here at all.” —B.B.