Take off your footwear and look inside. What does it say?��

If you’re reading this while wearing rock-climbing shoes, mountaineering boots, ski-touring boots, hiking boots, nordic ski boots, or telemark boots, chances are good you’ll see some variation of Made in Italy printed on them. Which means that what’s on your feet was either designed, molded, glued, or sewn in or around one place—a northern Italian town called Montebelluna. Here, where the Venetian Plain bunches like a door-stopped carpet against the foothills of distant white mountains, is the cradle of alpine craftsmanship for the foot.

These days, thanks to the globalization of manufacturing, we rarely know where our stuff comes from. Yet Montebelluna and its scarperi (bootmakers) have endured. The generations-deep wisdom that abides here has made this place the Alexandria of technical-shoe know-how. , , , , , , , , , , and others—all still perform at least some of their work here, whether that involves first sketches or full-on assembly. Those Dynafit ski-touring boots in your closet? Made in Montebelluna. Your Scarpa climbing slippers? Ditto. That pair of Fischer cross-country ski boots? Yup. Even the machines that make the machines that make the shoes are created here.

So the companies keep coming. When Canada’s Arc’teryx designed its cutting-edge line of mountain shoes and boots, it hired Montebelluna native and former Dynafit product manager Federico Sbrissa. Today’s hottest running shoes, Hokas, initially bubbled up inside the brain of a Tecnica employee. And before K2 unveiled its first line of ski boots a few years ago, what did it do? The New World looked to the Old, and to the town that lies where Italy’s boot meets the Alps.

To reach Montebelluna (population 30,800), you take the autostrada north from Venice and exit before getting to the mountain foothills, passing names that most Americans know from gourmet delis, like Piave and Bassano del Grappa. You drive past vineyards and 16th-century villas and factories—often seeing them all bunched together, the concept of zoning having come late to Italy. Downtown Montebelluna, 40 miles northwest of Venice, looks clean and feels prosperous, with its wide main square, Piazza Negrelli, surrounded by gelato-hued buildings. There are an inordinate number of shoe stores here. In the industry, though, “Montebelluna” is really shorthand for a constellation of 28 surrounding towns and villages that all make things for your feet.

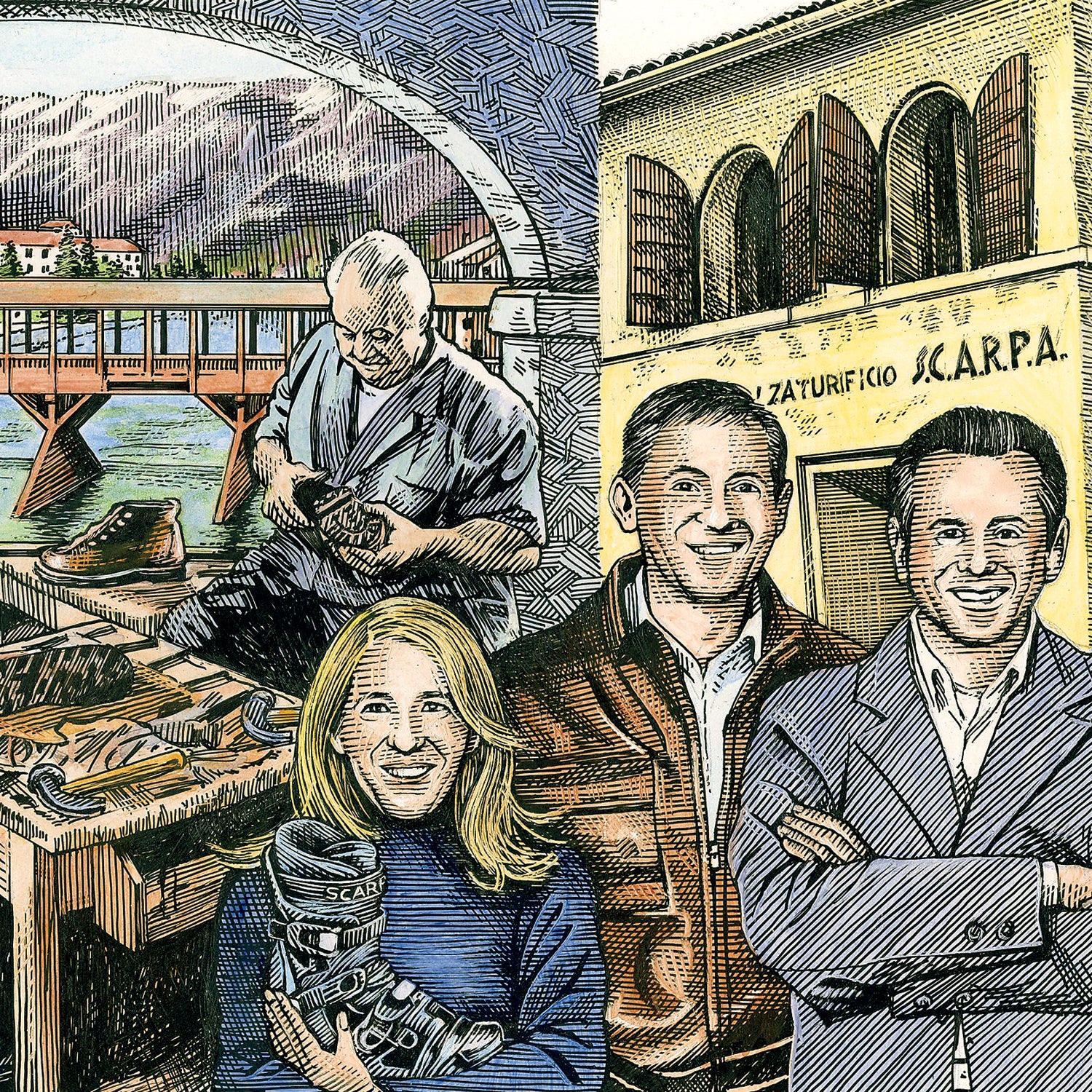

The Scarpa shoe factory sits just down the road in Asolo, on a street named for Enrico Fermi. Today, Scarpa is run by the second generation of the Parisotto family: Sandro is CEO; Cristina, his sister, heads design and product development for the mountaineering, trekking, and lifestyle lines; cousin Davide monitors production and R&D. Over the years, la famiglia Parisotto has tallied a résumé of firsts: The first Gore-Tex-lined hiking shoe. The first plastic mountaineering boot. The first plastic telemark boot, the game-changing Terminator. But something else also made me want to knock on Scarpa’s door: at a time when the supply chain has scattered across the planet, the company still makes 65 percent of its footwear right here.

Davide Parisotto is 52, with close-set eyes and steel-colored hair that he sweeps back from his face with practiced worry. The production floor is Davide’s domain, and most days he can be found wearing a blue factory smock with the company’s logo over his heart, along with a pessimistic expression on his face, his eyes always scanning for new problems. By necessity and temperament, Davide is blunter than his front-office cousins. When I asked how many models of footwear Scarpa makes, he replied, “Too many.” (Actually, there are about 220.)

Standing in the warehouse among boxes of bootlaces made down the road, along with pallets of incoming Vibram soles from China, Davide gave me a thumbnail company history, which began with beer. A century ago, Italy was fashionable with vacationers from Britain, including an Anglo-Irish businessman named Rupert Edward Cecil Lee Guinness, second Earl of Iveagh. (Yes, he was part of that Guinness family.) Guinness owned land around Asolo and saw that there were a lot of poor, skilled shoe-makers and laborers in the vicinity who needed work. In 1938, he put up the money to start a company called SCARPA, the letters standing for an association of footwear manufacturers from the mountain area of Asolo. In 1956, the three young Parisotto brothers—Francesco, Luigi, and Antonio—bought the company from the mayor and the local prior. They started small, making five shoes a day and peddling them to shops in neighboring towns on weekends.

Davide is blunter than his front-office cousins. When I asked how many models of footwear Scarpa makes, he replied, “Too many.” (Actually, there are about 220.)

Shoemaking here goes back much further than that. Venetian shoe artisans formed a collective in 1278. Later the craft divided: fine shoes migrated to the banks of the nearby Brenta River (where Prada and other big-ticket shoes are still being made), while the makers of laborers’ wooden clogs followed clients and materials to the forested foothills to the north, where Venice harvested the timber to build its famed fleet. By 1872, according to local historian Aldo Durante, there were 55 shoe shops in the Montebelluna area. At the start of the 20th century, there were 200.

Shoes built for play evolved from shoes built for work. After World War I, as people started to head into local mountains in pursuit of fun, the caulked, Norwegian-welt boots designed by the Montebellunesi for foresters were developed into hiking boots, which soon doubled as ski boots. Shoemaking families were established: The Garbuios of Dolomite. The Caberlottos, later of Caber ski boots, and after that the founders of Lotto. The Vaccaris of Nordica. The Parisottos.��

After World War II, Montebelluna took off by doing what it does best, capitalizing on tradition while embracing innovation. At the Museo dello Scarpone e della Calzatura Sportiva—a museum of outdoor footwear housed in a 15th-century villa—you can see a knee-high boot made of deer fur and opossum liners, created by Dolomite and worn on the first ascent of K2 in 1954. There’s also a 1968 Nordica Astral Super, the first ski boot made using the modern method of injected plastic. Bob Lange had fashioned the first plastic boot in the U.S. in 1962, but Montebelluna’s improvement on his cast-mold method soon made this area the world leader in ski-boot production. Millions of pairs were cranked out annually.

“Montebelluna,” the saying went, “makes the world ski.” By the end of the 1970s, the area boasted 12,000 employees in more than 500 footwear-related companies, resulting in one of the highest per capita incomes in Italy.

Davide pushed through a door that opened onto a single large room: Scarpa’s factory floor. There were big machines and ventilation fans and tubes that reached toward the ceiling. Every bit of air was filled with a low, productive clamor. He pointed to a wall where thousands of things that looked like cookie cutters were racked on shelves. These were patterns used to stamp all the pieces—tongues, uppers—that make every shoe, in every size.

Sitting near us, an employee was using a laser-guided cutter, which reduces waste. A few steps away, a dozen women in blue smocks bent over sewing machines beside bins of freshly cut pieces. One guided material carefully past the needle, marrying the gusset of a chocolate Ladakh GTX backpacking boot to its upper. Around the corner, men dipped small paintbrushes and applied glue to half-shaped climbing and mountaineering boots. A slow green conveyor belt laden with half-formed shoes inched past, looking like one of those devices that trundles unagi at a sushi-go-round joint.

Then I saw the artificial “feet”—thousands of them, bins of green and gray lasts, or molds, around which every shoe is shaped. As much as anything, the curves and volume of these lasts determine whether your shoe fits well. They’re made here, and there’s a precise art to doing it properly.

“We make different shoes every hour, or even every five minutes.” Davide laughed. “This is a big problem for me. This is why I have gray hair.”

“Norwegian feet are very big,” Davide said. “Asian is completely different. Japanese feet are very large here, in this part,” he added, grabbing the widest part of his foot.��

A company like Scarpa can produce a popular boot like the Kailash to cater specifically to markets in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. The lasts stay in the shoes for 24 hours. Removing them too early, Davide said, is like taking wine from the bottle prematurely.��

Near the assembly line, an old man, nearly bald and owlish in his eyeglasses, slowly took shoes from a rack, looked each one over, then placed it on the conveyor. This was Francesco, Davide’s 88-year-old uncle. (Luigi, 85, Davide’s father, sat around the corner, watching Scarpa’s best-selling Maestrale ski boot come off the line.) The two live in apartments above the original factory, just a two-minute drive away, where Scarpa molds those boots. They still show up nearly every day. When I asked why, the sons shrugged. “When they have come to the factory their whole life, you cannot tell them to stay home,” Sandro told me.

At the other end of the row sat three dozen racks stacked high with pumpkin-colored Phantom Guide mountaineering boots, Marmolada trekking shoes, and Nangpa-La XCR trekking boots, their tongues hanging open like dogs ready to go outside. A full day’s work? “Just this morning,” Davide said. “We make different shoes every hour, or even every five minutes.” He laughed. “This is a big problem for me. This is why I have gray hair.”

I asked Davide how many people touch a pair of the company’s shoes. He thought and said, “Probably 50.” He made a heavy sound. “People have no idea.”

Over the past 30 years, manufacturing has changed dramatically, and that’s had a big impact on Montebelluna. I went down the road to meet a man who’s seen it all, from the old days of leather to the modern era of carbon fiber.

Mario Sartor is 69, with a push-broom mustache and bifocals that dangle from a cord around his neck. He started sewing moccasins with his father at age 11. Today he oversees design for Salewa’s trekking shoes and Dynafit’s trail-running shoes and ski-touring boots. During a long career with Garmont, Dynafit, and others, he has designed 80 to 100 ski-boot models, about 50 trekking boots, and upwards of 60 cross-country ski boots—most recently, Dynafit’s popular TLT 6 boots. In his free time he makes wine. People call him Super Mario.

The design offices where Sartor and his younger colleagues work are almost spare. That’s because Dynafit doesn’t produce its own boots anymore, that work having been outsourced to multiple factories down the road. To see it, we got in a car and drove five minutes to an anonymous industrial park. Inside a boxy, windowless building, the place was filled with machinery, the smell of warm plastic, and the sounds of banging and wheezing.

This space was home to one of a series of suppliers that produce and assemble Dynafit’s line of 14 ski boots. The owner showed us how hail-size pellets of Pebax or Grilamid plastic are fed into a silo and mixed to Sartor’s specifications to create a shell that’s the ideal blend of stiffness, comfort, and affordability. The pellets were heated to 464 degrees Fahrenheit, and the molten goop was then injected into a mold by what looked like a giant screw. On the far end of an assembly line, a worker collected the results: sky blue boot cuffs for next winter’s women’s TLT 6.

“The secret of the right project is always to choose the right supplier,” said Sartor, ribbing the owner. “Unfortunately, he costs like gold. If you want a beautiful woman, you have to pay for her.”

Some of Montebelluna’s production started to migrate to Eastern Europe before the Berlin Wall fell. Assembly lines have since moved all over the world. A few days earlier, visiting Tecnica, I found that the R&D rooms were still full of folks sketching up shoes but that the huge factory building had nearly gone dark. Today, Hungary builds the conglomerate’s Nordica and Tecnica ski boots; Slo-vakia, Romania, and Vietnam rivet its hiking shoes; and Vietnam and China box up Rollerblades.

“It became a cost issue,” said Alberto Zanatta, whose grandfather and father built the company. In northern Italy, it’s expensive to make things that require a human touch. As Scarpa’s Sandro Parisotto told me later, if a worker makes 1,200 euros per month, a company must pay roughly 2,000 euros in payroll taxes. If you want to make a trail-running shoe today, you almost have to produce it in China, the reigning king of EVA, the stuff that cushions the soles.��

“The brain has stayed here but the hands have left,” Andrea Nalesso, Salewa’s general manager for footwear, told me. “You take advantage of the best available expertise on the market,” he said. “The expertise is always Italian.”

When I ask about the prospects for Montebelluna, the Italians, being Italians, all had strong opinions. To stay relevant, the skeptical among them said, this place needs better roads, a better tax structure, and a modern research facility.��

The optimists still see a bright future. The towns long ago stopped leaning solely on the fortunes of mountain shoes. Today they are a mecca for all kinds of footwear. Sidi makes its cycling shoes not far from Scarpa. Alpinestars motorcycle boots is next door, Nike designs its soccer shoes here, and Converse has offices in the area. Even so-called “brown shoe” companies have set up shop.

I thought of the last stop on our tour. It was yet another nondescript industrial park. Hundreds of goblin green Dynafit Neo PX-CP boots were being assembled—gussets glued to boots, tongues and buckles riveted into place, stickers affixed that read Made in Italy. Mario called us over to admire a machine that attached soles to ski boots by drilling all eight screws without human input. Zip. Zip. Zip. The little Italian grandfather who’d once built boots of leather at home admired it for a while.��

Finally, Super Mario said, “Bella, eh?”

The Montebellunas of America

Boulder, Colorado��

American Rec (Kelty, Sierra Designs, and Ultimate Direction), Crocs, Dynafit, GoLite, La Sportiva, Newton Running, Pearl Izumi, Sea to Summit, SmartWool��

Santa Barbara, California

Channel Islands Surfboards, Decker Outdoor (just north; owner of Hoka, Sanuk, Teva, and Ugg), Patagonia (30 minutes west), Toad&Co

Salt Lake City

Black Diamond, DPS Skis, Goal Zero (in nearby Bluffdale), Petzl, POC, Pro Bar, Salomon (in Ogden), Scott Sports USA

Orange County, California

ASICS, Hurley, Quik-silver, Rip Curl, Vans, Volcom

Portland, Oregon

Adidas, Columbia Sportswear, Gerber Gear, Keen, Leatherman, Nau, Nike, Poler Stuff

A Brief History of the Ski Boot

1880s:��In New England, industrial sewing machines mass-produce a thick-soled boot with a thin upper shell of leather.��

1955:����The ski-boot buckle is invented in Switzerland by Hans Martin.

1962:��Bob Lange creates the all-plastic boot. More than 50 years later, the ’62 Lange is still the standard boot design.��

1969–70:��Australian Sven Coomer creates the customizable boot liner. Nordica’s Olympic boot is the first to use the feature.��

1972:��Michigan brothers Chris and Denny Hanson develop the first commercially viable rear-entry ski boot.

1987:��More than 80 percent of boots sold worldwide are rear entry. By the 1990s, the design will lose ground in favor of better-fitting, overlap-closure boots.

2009:��The Apex Sports Group in Boulder, Colorado, introduces the Apex Boot System: boot, chassis, and custom liner. They’re as comfortable as snowboard boots without sacrificing performance.