The call volume at the Surf Station picked up dramatically on Friday, September 21. Thanks to a concerned customer, employees at the Saint Augustine, Florida,┬ástore had known for about two days that a scammer was impersonating their business online, but Friday was when things ÔÇťgot heavy,ÔÇŁ says manager Tony Berracol.

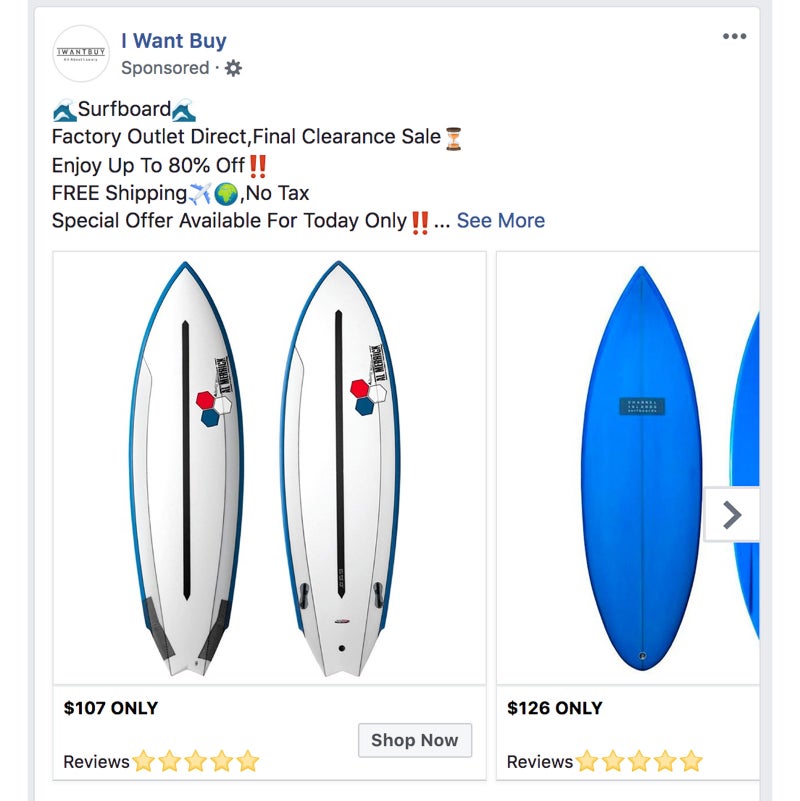

The problem: A┬áscammer had grabbed assets like logos and photos from the legit Surf Station website, then┬á┬áon a┬ásimilar URL. Brand-new boards from premier makers like Channel Islands, Firewire, and Lost were advertised at 70┬áto 90 percent off. Four other doppelg├Ąnger sites, likely from the same scammer, also appeared.

Berracol says the scammers bought ads on FacebookÔÇöa common tactic among crooksÔÇöto target potential victims. It worked. ÔÇťWe must have gotten 100 phone calls that Friday,ÔÇŁ┬áhe says. ÔÇťSome were people who were about to buy [products] or had already checked out. ItÔÇÖs slowed down since then, but people are still getting ripped off.ÔÇŁ┬áSome of his customers called wondering when an order would be shipped, while others┬áwere concerned they had gotten scammed. Still others were simply tipping off the shop to the existence of the other sites.

Outdoor gear is undeniably expensive. Coolers for $300. Jackets that cost $750. Road bikes that routinely run to five figures. But it isnÔÇÖt cheap to make. ÔÇťYou canÔÇÖt even manufacture surfboards for the cost these guys are charging,ÔÇŁ says Berracol. ÔÇťPeople are unaware of the real price.ÔÇŁ

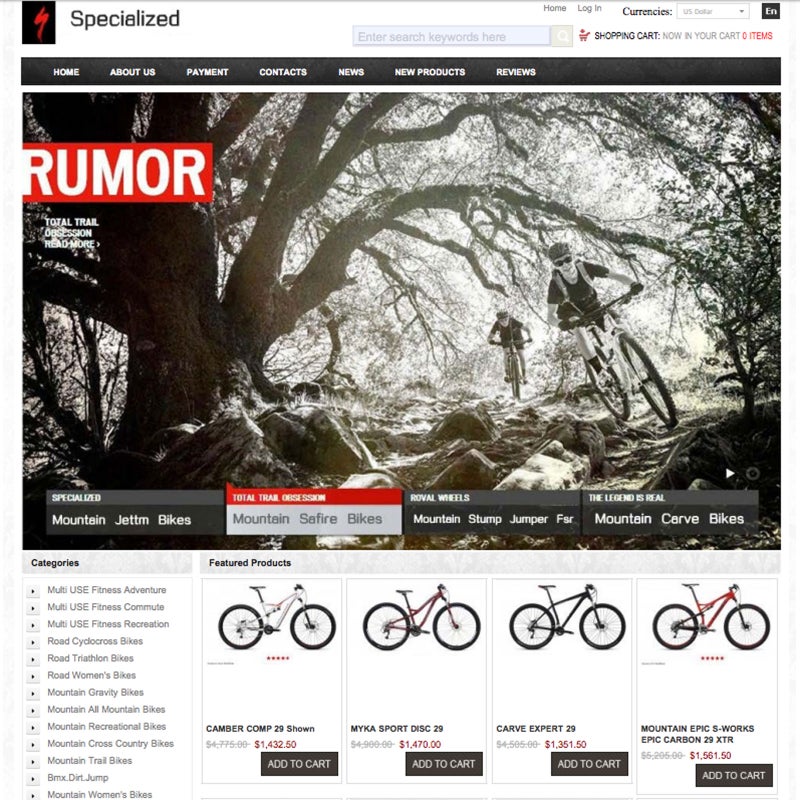

The industry has struggled with scams like this for years. ÔÇťI saw my first outright scam site in about 2010,ÔÇŁ says Andrew Love, the longtime director of brand security for Specialized Bicycles. LoveÔÇÖs job is to battle criminals trying to capitalize on SpecializedÔÇÖs business. Much of his work┬áinvolves trying to shut down online sellers hawking counterfeit goods. But he also has to fight scammers who have no intention of delivering any products, even fake ones. ÔÇťIÔÇÖve knocked down hundreds of these,ÔÇŁ Love says.

The scammers sometimes imitate a companyÔÇÖs own site, under the factory-outlet ruse. But they also impersonate retailers like the Surf Station. Their modus operandi┬áfollows a pattern: the scammers set up a site with assets like photos, logos, and product copy lifted from legitimate sources, offer jaw-dropping discounts, and then flood Facebook and other social-media platforms with ads. Because advertisements arenÔÇÖt expensive, they┬ácan be targeted to particular demographics and┬á╠ř┤ă░¨╠ř▒▒╣▒▓ď , like searching ÔÇťsurfboard saleÔÇŁ on Google.

Love is currently battling a site that advertises S-Works tarmac discs for $260, a nearly 98 percent markdown from the admittedly astronomical retail price of $11,000. That discount is completely unhinged from reality. But scammers play on human psychology, appealing to narratives like how the traditional retail model involves too many middlemen, and that you can save 70, 80, or 90 percent with their direct model.

Specialized isnÔÇÖt the only bike-industry target; previous victims include ┬áand Trek. In outdoor apparel and shoes, has been hit, as has┬áthe┬á. One site on high-end cooler brands, including┬áYeti. ItÔÇÖs a persistent enough problem that Trek a page on its website detailing how consumers can determine whether a seller is legitimate or not.

Early scam sites were often poorly done, but todayÔÇÖs versions are becoming increasingly sophisticated. ÔÇťA [Specialized]┬áretailer in the UK┬áhad a similar situationÔÇŁ to the Surf Station, Love says. ÔÇťThe┬áscammers even copied employee headshots.ÔÇŁ Some scammers will generate a tracking number for shipping. Others will send a physical item of some┬ákind, perhaps┬áa keychain or other trinket,┬áintended to show that a┬áproductÔÇöthough not the one that was orderedÔÇöwas┬áin fact delivered, says Eddie Toy, the Surf StationÔÇÖs web developer. That helps the scammers fight back legally when jilted buyers lodge complaints.

Scammers use social-media ads for the same reason legitimate companies do: theyÔÇÖre a cost-effective way to reach specific audiences. (This year┬á66 percent of digital advertising dollars will be spent on Google and Facebook properties, .) ÔÇťWeÔÇÖve noticed that a lot of this starts on Facebook and Instagram, because thereÔÇÖs a lower barrier to entry for placing ads on those platforms,ÔÇŁ says Trek spokesman Eric Bjorling, adding that Trek actively advertises on several social-media platforms. ÔÇťYou can make an ad thatÔÇÖs similar to the real brandÔÇÖs ad, and itÔÇÖs hard to tell the difference when youÔÇÖre scrolling your feed.ÔÇŁ┬á

ÔÇťFacebook prohibits advertisements that are deceptive, false, or misleading,ÔÇŁ a Facebook representative told me via┬áe-mail. She said that Facebook unpublished the fraudulent Surf Station ads and disabled the account promptly, noting┬áthat none of the ads were reported for intellectual-property violations. But Surf Station staffers provided ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° with a copy of an IP violation report submitted to Facebook on September 24, and said they continued to get reports of buyers throughout that┬áweek. ItÔÇÖs possible that the scammer had multiple accounts set up to purchase ads, according to Toy. The Facebook spokesperson told me that all ads go through an automated review process that includes an analysis of ad text, images, and website landing pages that the ads lead to, and in some cases a human review as well. But the Facebook system missed the clear signs in the Surf Station case, such as promised discounts of up to 90 percent, and a landing page with weak SEO presence that had been live for less than two weeks. The system doesnÔÇÖt catch everything, the Facebook spokesperson admitted, but she contended that Facebook continues to add staff and resources to fight the problem of scams.

How can you tell when┬áa site is┬ánot legitimate?┬áSome clues our sources have mentioned: beware if a┬ásiteÔÇÖs┬ácontent includes sloppy product copy or pixelated, low-resolution images,┬áproduct specs donÔÇÖt match those of the┬ámanufacturer,┬áand the only contact information is an online form. Legitimate sellers list┬áphone numbers and e-mail contacts. Another telling sign is if the site is brand-new, but a┬á will show its┬ácountry and date of registration, even if other contact information is hidden.

If you see a scam, there are several things you can do: Alert the manufacturer or retailer. Flag the ads on social media. And if you got scammed, with the FBI and dispute the charge with your credit-card provider. (They should communicate quickly and directly with you, but donÔÇÖt expect much from other organizations.) Despite concerted efforts by the Surf Station staffers, it took almost two weeks to knock the scam sites offline. They told me that they didnÔÇÖt receive more than an automated-form response to their requests from┬áthe hosting company, Facebook, and the FBI. The scammer, meanwhile, has registered over 3,000 domains this year, says Berracol.

ItÔÇÖs hard to avoid the almost instinctual response to a great deal, and sources we spoke with were sympathetic to the lure that these sites offer. Love says that even though he does brand protection for a living, heÔÇÖs been suckered. Innovations like AmazonÔÇÖs dynamic pricing make determining a fair cost even harder. ÔÇťYesterday┬ámy daughter lost her Crocs, and IÔÇÖm looking for a pair on Amazon, and I donÔÇÖt know whatÔÇÖs real and whatÔÇÖs not,ÔÇŁ he says, laughing. He saw shoes ranging┬áfrom $15 a pair to $50.

And scammers prey on victimsÔÇÖ passion┬áfor their┬ásports. ÔÇťPeople are just trying to get a great deal,ÔÇŁ says TrekÔÇÖs Bjorling. ÔÇťTheyÔÇÖre trying to enjoy something that would normally be unattainable to them.ÔÇŁ