Most climbers agree on one thing: rappelling is terrifying. While the concept of using a rappel device to descend a rope is simple, in practice it requires the utmost attention to detail. This proves difficult when youÔÇÖre mentally and physically exhausted after a long climb and all you can think about is cheeseburgers. The margin for error is razor thin,┬áand accidents often result in death.

Those risks are compounded by the fact that most big climbs require multiple rappels to get to the ground, which adds logistical challenges. If you want to rappel more than 30 to 35 meters (roughly 100 to 115 feet)┬áat a time (or half the length of one rope), you need to bring along another rope. But a second rope adds weight, and when youÔÇÖre committing to big days in high mountains, extra pounds matter.┬á

, a new detachable anchor system from French climbing-gear manufacturer Beal, could solve that problem, allowing you to rappel the full length of a single rope, then retrieve the rope by pulling on it a certain way and keep descending. Weighing in at 3.2 ounces and packing down to the size of a beer can, the device seemingly offers a weight-saving solution. But while making it possible for climbers to get to the ground with fewer rappels and thus descend faster, the mechanism it uses could prove risky and make rappelling more dangerous. We tested it out to see if the pros outweigh the cons.

How It Works

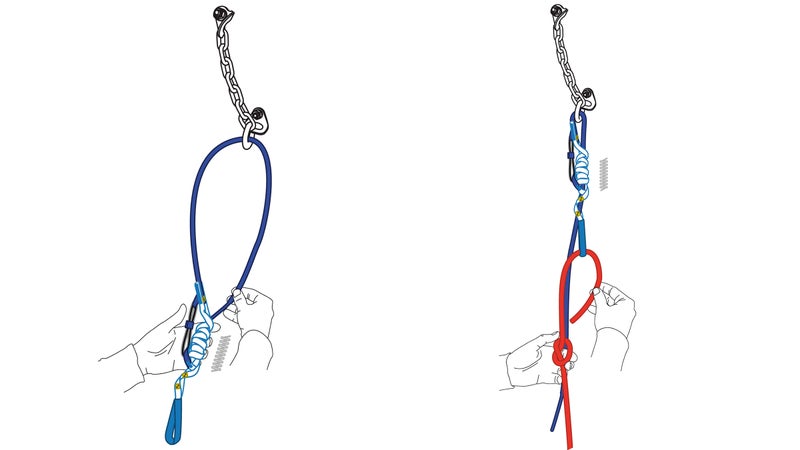

The design of the Escaper is simple but brilliant. ThereÔÇÖs a four-foot section of dry-treated dynamic climbing rope with┬áa Dyneema wrap, a bungee cord, and an attachment loop at the bottom. Thread the end of the Escaper through the anchor and then all the way down through the Dyneema wrap, which resembles a friction hitch. Tie┬áyour main rope to the attachment loop below the Dyneema wrap. As with a┬á, pulling on the Dyneema wrap (or, in this case, weighting it for rappel)┬ácauses it to tighten, effectively locking it in place. The rappeller can then descend.┬á

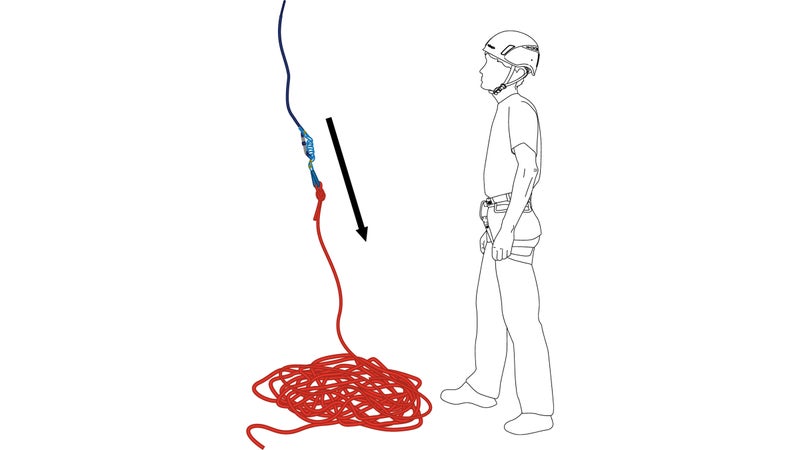

Once on the ground, itÔÇÖs time to get your rope back. Pulling and releasing the rope sharply causes the bungee to stretch and then spring back up, moving the Dyneema wrap along with it. With each pull and release, the Dyneema wrap┬áinches down the Escaper rope. Yank the rope enough times (Beal says it takes a minimum of eight, but in our testing it was closer to 12)┬áand the friction hitch inches right off the end of the Escaper. The deviceÔÇÖs rope segment slides through the anchors, and the Escaper and climbing rope fall to where you can retrieve them.

Beal isnÔÇÖt just marketing this as an emergency tool; the company envisions it as a tool for competent climbers familiar with the terrain to routinely make full-length, single-rope rappels, lightening their packs and getting to the ground faster.┬áÔÇťThe name is Escaper, so it is┬áfirst a backup device,ÔÇŁ says┬áa Beal representative. ÔÇťBut when you know the routes, you can use the Escaper as a standard way to rappel with a┬ásingle rope. So┬áitÔÇÖs a back-up system, but not only a backup system.ÔÇŁ

Why It Might Be Dangerous

Holding a Rappel

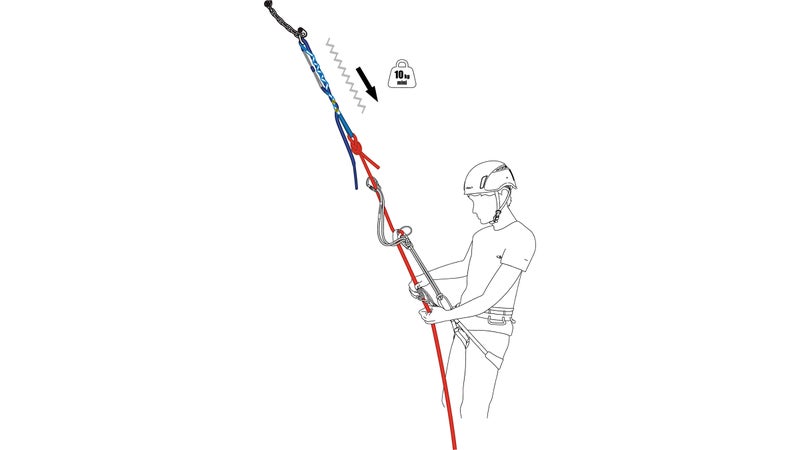

The device is designed to come unattached after a rappel, which raises the question: Could that happen┬áduring a rappel? Rappels are rarely straight or free-hanging. Climbers will likely unweight or partially unweight the rope as they come┬áto ledges or bulges. Theoretically, unweighting the rope mid-rappel could mimic the yanking and releasing action that makes the Escaper inch over itself and ultimately release. In the instruction manual, Beal requires a consistent weight of ten kilograms┬á(22 pounds) to keep the bungee taught, but how do you know if youÔÇÖre exerting the minimum┬áamount of force on the device to keep it engaged?

Asked whether unweighting the rope could mimic the pull-release motion of rope retrieval, the Beal representative┬ásays, ÔÇťIt is possible, which is why we say you need to maintain ten kilograms of weight on the rope.ÔÇŁ

But the representative adds that ÔÇťthe pull and release actions┬áare very active movements,ÔÇŁ meaning that they should be quicker and more forceful┬áthan those used when unweighting the rope during a rappel.

Backing It Up

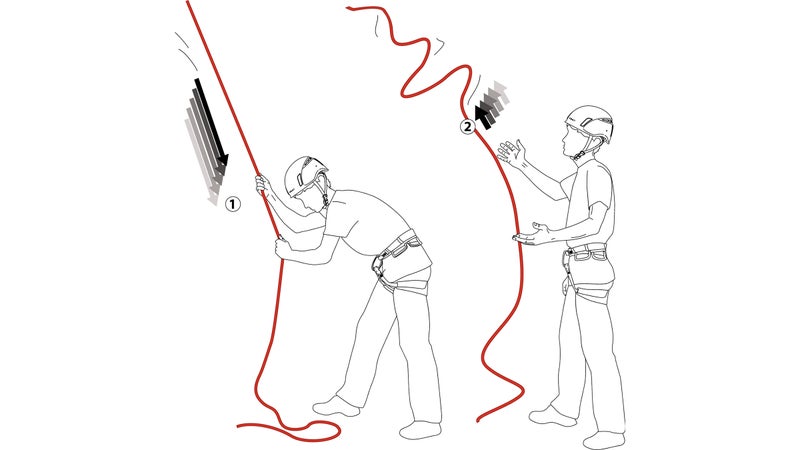

Beal recommends using a backup knot and a testing system for each rappel: fix the Escaper with a knot at the end of the rope segment and send your partner down while you stay at the anchors to make sure that the friction hitch ╗ň┤ă▒▓§▓ďÔÇÖt move during rappel and does move when yanked for retrieval. Then you can remove┬áthe knot and rap┬ádown. This requires communication between you and your partner, which isnÔÇÖt always possible. Consider this situation: You notice┬áa problem during your partner's rappel, but your partner is now 200 feet below and out of earshot. What are you┬áto do?

With respect to that scenario, the Beal representative┬ásays that the Escaper isnÔÇÖt any different from a typical two-rope rappel. ÔÇťWhat can you do when you rappel with your two strands of half rope and the knot is stuck somewhere?ÔÇŁ he asks. ÔÇťThe Escaper is as efficient as any other method to rappel down.ÔÇŁ

Rope Retrieval

Will you reliably be able to retrieve your rope after you rappel in all conditions?┬áTesting the Escaper as a demo on a trade-show floorÔÇöas Ed Crothers, who directs┬áthe ┬áclimbing-instructor program, didÔÇöwent smoothly. But that was under ideal conditions. ÔÇťIt was in a free-hanging, vertical orientation, attached to an eyebolt, which nearly eliminates the friction that would be found in many climbing situations,” Crothers says. ÔÇťI still have a lot of questions.ÔÇŁ

For instance: What happens when you factor in the weight of a full 60- or 70-meter rope or a wet rope? What if the rope runs over┬áledges, cracks, or┬áslabs, causing friction? In the field, yanking your rope won't always be┬áas easy as it is in a┬ádemo situationÔÇöand if youÔÇÖre more than one rope length off the ground, getting your rope back is essential.

Our Test

Our team of testersÔÇöme and several experienced climbers and canyoneers, including Spencer McBride, a guide in Zion National ParkÔÇöused this device in several situations: on a test┬áanchor at chest height, on single-pitch climbs, and on multi-pitch climbs┬áwith one big rappel to the ground.┬áIn all these situations, the rope ran straight,┬áwith few┬áledges┬áand little contact with the rock, and the Escaper performed perfectly, staying put during rappel and coming free after about a dozen harsh tugs from the ground. However, we couldn't mimic a long, jerky rappel, weighting and unweighting the rope, without abandoning our backup protocol, which none of us felt comfortable doing.

As for retrieving the rope after rappel, we found that pulling a 70-meter rope with the added resistance of the Escaper was quite similar to pulling the added weight of a second 70-meter rope on a standard double-rope rappel. The biggest difficulty for me was getting the snap of the pull-release motion, especially with more than half the rope out. It requires a powerful, coordinated, full-body motion at odds with the slow and controlled method of pulling ropes in a standard rappel.

The Upshot

The Escaper isnÔÇÖt the first device of its kind. In the late fifties, French climber and inventor Pierre Allain created the Decrocheur Allain, a metal device with a spring-loaded hook that popped off the anchor as soon as it was unweighted. It never caught on. A similar approach involves hooking a standard piece of aid-climbing gear called a fifi hook to the anchorÔÇöit, too, requires consistent weight during the entire rappel. Some climbing guides use a special┬árope hitch that comes undone with a few pulls, but it has resulted in at least one death.

The Escaper is the first device designed to┬áallow the user to unweight the rope multiple times before it releases. And┬áunlike similar tools and tricks, Beal is claiming it isnÔÇÖt just a last-ditch┬áemergency device. As the Beal representative┬ásays, Beal wants the Escaper to become a regular part of the experienced climberÔÇÖs kit.

For Ron Funderburke, education director at the , itÔÇÖs the lack of certain caveats and concerns in BealÔÇÖs instruction manual┬áthat are the cause skepticism. ÔÇťThey donÔÇÖt mention icy conditions. They donÔÇÖt mention vegetated or loose terrain, where the Escaper could dislodge debris or get stuck,ÔÇŁ he says. ÔÇťAre we to believe that none of these circumstances impose conditions on the EscaperÔÇÖs use?ÔÇŁ (Though as the Beal representative┬átold┬á║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, ÔÇťBeal feels like they covered this in their product-use guidelines,ÔÇŁ pointing to a bullet in the instruction manual┬áthat warns that “in wet or icy conditions the system will become more susceptible to abrasion and lose strength.ÔÇŁ)

With the device so new┬áand testing limited, itÔÇÖs nearly impossible to answer many of these safety concerns right now. In the meantime, most of the professionals we spoke with encourage climbers and canyoneers to think of the Escaper as an emergency-only device┬árather than a replacement for a conventional rappelling setup. More important, they emphasize that only advanced and experienced climbers should use it.

ÔÇťIn the hands of the unaware or incompetent, this device could be deadly,ÔÇŁ Crothers says. ÔÇťBut if over time it proves itself to be a viable, versatile tool, then it could be a game changer.ÔÇŁ