By now youŌĆÖve probably heard the news: your favorite fleece sheds┬Ā┬Āevery time itŌĆÖs washed. Those fibers often skirt through┬Ā┬Āand make their way into aquatic organisms that┬Āeat the floating fibers. ThatŌĆÖs bad for the fish, because the fibers are vectors for toxins and can retard their growth, and it could be bad for people who eat the fish.

This shedding┬Āputs outdoor manufacturers in a bind: many┬Āwant to protect the outdoors, but they also want to sell product.┬ĀConsumers who love their warm fleece are also faced with a dilemma.┬Ā

Some brands have taken steps to address the threat of┬Āmicrofibers, which are considered a type of microplastic pollution. In 2015, Patagonia asked university researchers to quantify how much fiber its products shed during laundryŌĆöthe answer was┬Āa lot. And the┬Ā┬Āhas convened a working group to start examining microfiber pollution. But hereŌĆÖs the thing: rather than using money to develop a process that┬Āprevents the shedding, most┬Ābrands are still focused on defining their culpability. Because there are other sources of microfiber pollution in the sea, such as fraying fishing ropes,┬Āthese┬Ābrands want to be able to know for certain how much theyŌĆÖre contributing before they move┬Āfurther.┬Ā

That wonŌĆÖt be an easy task, but , an REI-like retailer headquartered in Vancouver, recently gave microplastics researchers at the┬Ā┬Āa $37,545┬Āgrant to help scientists develop a tracking process. The yearlong project will be led by the aquarium's ocean pollution research program director and senior scientist Peter Ross.┬ĀThe first step is to create a database of fibers from up to 50 different textiles commonly used in MECŌĆÖs house-brand apparel.

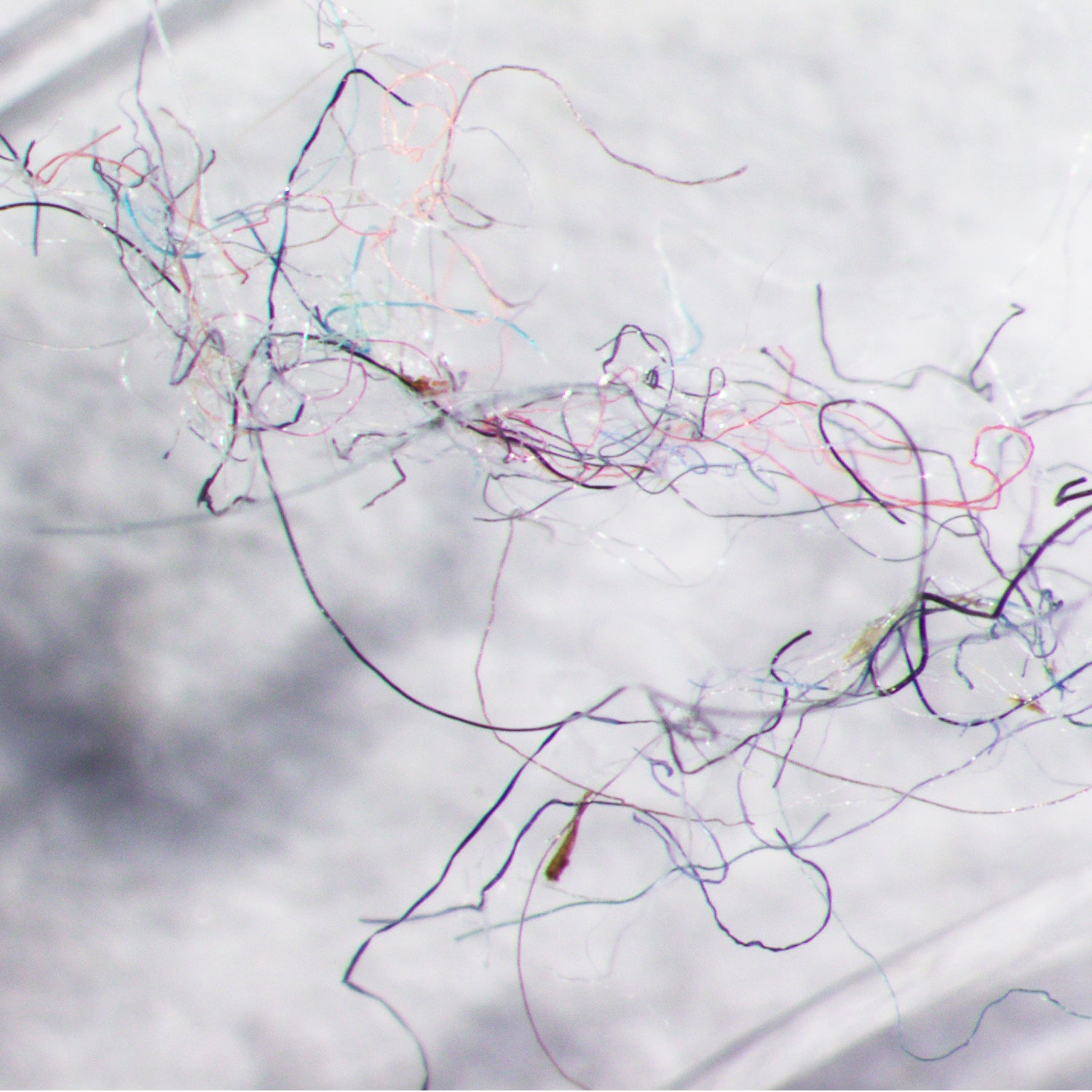

This wonŌĆÖt be a simple spreadsheet with the names of the polymers, like polyester or nylon. Each piece of outdoor apparel is treated with chemicals like a durable water repellant (DWR). Then thereŌĆÖs the┬Ākaleidoscope of colors in each brandŌĆÖs catalog. Those variants give the fibers a unique profile, sort of like a fingerprint. To capture those fingerprints, Ross and his team will use a machine called a┬Ā, which looks at the fibers on a molecular level.

Once that database┬Āis created, the researchers will subject the fibers to saltwater, sunlight, wave action, freshwater, and bacteria┬Āto mimic the types of weatherization that they would experience in the field. In fact, one set of fibers will be staked out in Vancouver Harbor and another in the Frasier River estuary. A┬Āthird set, for the sake of experimentation, will be artificially weathered inside the aquariumŌĆÖs lab. After increments of timeŌĆö30, 60, 90, and 180 daysŌĆöthe fibers will be reexamined and any changes in those polymer fingerprints will be documented and added to a database. The hope┬Āis that sometime in the future, a┬Ārandom synthetic microfiber could be pulled from Vancouver Bay,┬Āanalyzed, and determined to originate┬Āfrom an MEC jacket.┬Ā

Why bother with this experiment, as┬Āthe chances of finding an MEC fiber in the vast ocean are infinitesimally small? Ross says it will advance much needed basic research┬Āby shedding light on how fibers change once theyŌĆÖre in the environment. For MEC, this is a chance to lead the apparel industryŌĆÖs response to microfiber pollution by providing a protocol for tracing microfiber pollution back to its source.┬ĀTo prove that the protocol is effective and viable, it will need to be repeated many times, and, eventually, by different researchers in different labs. ArcŌĆÖteryx is next in line. The company will also be giving the aquarium a grant (it┬ĀwouldnŌĆÖt say how much) to study fibers coming off its apparel.

Skeptics like┬ĀStiv┬ĀWilson, campaign director for environmental activism┬Āgroup , thinks this is┬Āall a waste of time. We know thereŌĆÖs a problem, and he thinks brands should address it in manufacturing instead of delaying. ŌĆ£Eco-conscious outdoor brands keep telling me that more research needs to be done on the harms of washing synthetic fabrics such as fleeces and yoga pants,ŌĆØ┬Āhe wrote┬Ārecently. ŌĆ£Do we really need more research to tell us that spreading millions of trillions of persistent fossil-fuel-derived fibers from polyester clothing is a bad idea?ŌĆØ

MECŌĆÖs chief product officer Jeff Crook asserts that for one or┬Āa handful of outdoor apparel brands to redesign their textiles would do little to stop the larger flow of synthetic microfibers. Walk into any H&M or other fast-fashion retailer and youŌĆÖll be hard pressed to find clothes made only from natural materials. Motivating the largest apparel brands to act, he says, will require developing a tool for directly implicating their products as contributors to microfiber pollution.

Beyond all that, another major hurdle lurks. If or when apparel brands do succeed in redesigning textiles to reduce microfiber shedding, who will set that bar? That, says Crook, is where international standards are needed. ŌĆ£We have standards meetings at every trade show on things like sleeping bags, on camp-stove temperatures,ŌĆØ┬Āhe says. Without global standards that set a limit on how many synthetic fibers garments can shed while being laundered, he says, ŌĆ£weŌĆÖre all just dancing around this problem that we know is there: that clothes are sending┬Āmicroplastics into the marine ecosystem.ŌĆØ