We’re in the Middle of a Sports-Bra Revolution

Technological advances and a growing line of research have paved the way for a new class of support systems that are comfortable, look good, and fit a wide(r) variety of bodies.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

I’ve only known Helen Kenworthy for an hour when she asks me to take off my shirt. We’re in a small room with a mirror at the headquarters of Brooks Running in Seattle. Down the hall is��the shoe and apparel brand’s sports-bra design department, where well-lit work tables are piled with fabric cutouts, spools of zipper, and honeydew-size��plastic molds marked A cup,��B cup,��and so on.

Kenworthy, a senior bra developer for Brooks, wraps a measuring tape around my bust, then my rib cage, and tells me matter-of-factly that I have been wearing the wrong size bra��my entire life.

It’s not my fault. I—and, in fact, most women—don’t have the necessary information to shop correctly. Over the course of a month or even a day, Kenworthy explains, women’s chests can fluctuate by as much as a full cup or band measurement. Add in the fact that women’s breasts have unique compositions, each requiring slightly different forms of support, and you get a complex fit matrix that has to do with much more than a number and a letter. Sports bras are only just catching up to those realities.

“We’re retraining ourselves on how to develop, understand, and speak about fit preferences versus size,” she says. In other words, for Brooks and many other companies, the days of designing bras for support at the expense of comfort and then telling women to buy all their sports bras in one true size—even if that means they’re painfully tight—are over.

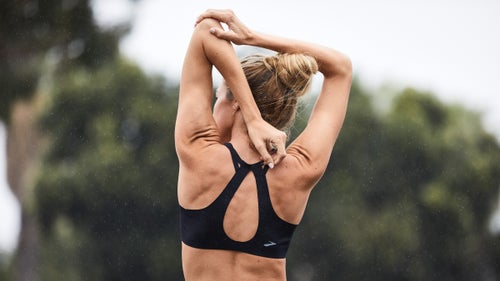

It’s more than a shift in mindset and sales tactics. I’d come to Seattle to get an up-close look at Dare, a collection of six sports bras��that launched in February and includes a crossback,��a racerback, a scoop-back, a high-neck, a zip-front, and a strappy model, all of which��run��from a 30A to a 40F. The new models look nothing like the sports bras that have defined its women’s line for decades.

Standby classics like the Juno, the Rebound Racer, and the Maia have distinctive features like Velcro shoulder straps, chunky back clasps, and contoured full-coverage cups. I had a strained relationship with those bras growing up. They were the only ones that worked for my 32D chest, but their bulky design made me feel ashamed of this part of my body,��apparently so outsize that��it��required metal and Velcro��or fabric up to my collarbones just to stay put.

The Dare styles retain that contoured shape, but everything else about them is entirely modern: laser-cut seamless edges, cups that are heat-molded to offer encapsulation—cupping each breast separately like your regular lingerie bra—without the need for underwire or extra stitching. They look good. And, as Kenworthy explains, they’re also far more comfortable without sacrificing support.

Brooks isn’t alone. Brands like Lululemon, Nike, and Reebok have all begun to revamp their offerings. For the first time, companies are investing in research and development to understand how breasts really move and how women want their sports bras to feel.