The Brotherhood of the Very Expensive Pants

Brit Eaton is the best of a curious breed of fortune hunters combing old mine shafts and barns across the West for vintage denim. He's discovered $50,000 worth of clothes in a single day, and his clients include Ralph Lauren and Levi's. STEVEN RINELLA joins him on a search for the blues.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

When I say that Brit Eaton was in the doghouse, I don't mean that he was in trouble with his wife. I mean he was literally inside a dog's house, with just his boots sticking out the door.

Bret Eaton on the denim trail, exploring for a basement

Eaton on the denim trail; Exploring a basement for forgotten clothes

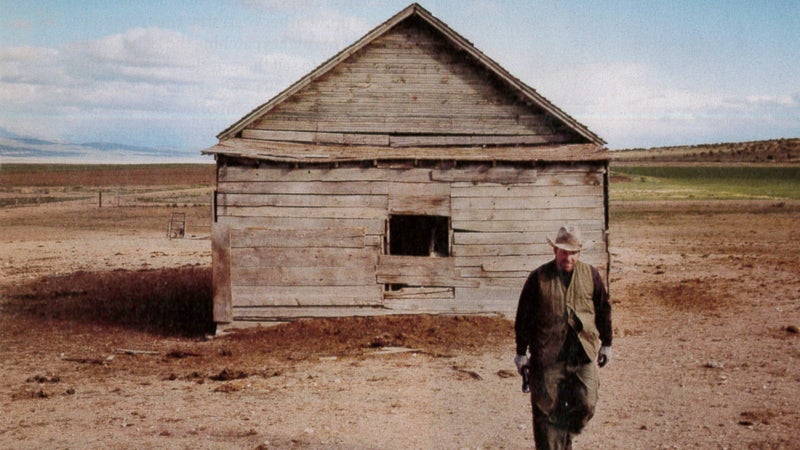

Eaton on the denim trail; Exploring a basement for forgotten clothesHunting for jeans in an abandoned shed

An old storage shed comes up bust

An old storage shed comes up bustLocal rancher, and Bret Eaton exploring in a loft.

A rancher Eaton visited; Searching an attic

A rancher Eaton visited; Searching an atticBret Eaton and ranchers

Eaton explains the value of old chaps to ranchers

Eaton explains the value of old chaps to ranchersI shone my flashlight over Brit's back to watch as he picked through the layers of old rags and clothes making up the bed of the occupant, a heeler with a baseball-size cyst on her belly. The dog's owner, a sixtyish rancher named Mike, from Modena, Utah, was too distracted to pay much attention to his visitor's behavior. Just that morning, Mike had learned that a mountain lion had somehow infiltrated the eight-foot-tall fence surrounding the headquarters of the Meathook Ranch, which his grandfather had established in 1903. He was cautiously watching a juniper thicket above a corral of calves. “I'm a son of a bitch on following tracks,” he was saying, “so you better believe when I say it was a big cat.” Mike turned back toward the doghouse and was surprised to see Brit's backside. He pointed a thumb at Brit. “People make money all sorts of ways, don't they?”

Brit, 38, is of medium height and solid build. He has a stern, square face that would be suitable on an evening newscaster if it weren't for a tangled scar above his lip that resembles a strand of barbed wire. He makes his living scouring the old ranches, ghost towns, abandoned homesteads, and forgotten antique shops of the American West in search of vintage clothes. When most people hear the word vintage, they think of bell-bottoms from the seventies, but Brit's definition of that word goes many decades deeper into American fashion. He has a particular interest in denim workwear from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His company's name is , and he sells his products, or “pieces,” to a disparate array of clients, including Hollywood wardrobe departments, private collectors, and companies like Levi's, Ralph Lauren, the Gap, and Dickies.

He is unabashed about his prowess; he freely admits to being “the best person in the country at finding old clothes, maybe the best in the world.” In a career spanning more than ten years, he has found hundreds of thousands of sellable vintage-clothing items. He once sold a pair of chinos with links to a soldier from the Spanish-American War to a Japanese collector for $12,000, his personal record for a single piece, and he's discovered as much as $50,000 worth of clothes in a single day. Brit is deathly afraid of competition there are a handful of other vintage-denim hunters so he's skittish talking about money. It's clear, though, that he earns an annual income pushing well into six figures.

In 2008, an Ebay seller auctioned a pair of circa-1980s, candle-wax-encrusted Levi's for $36,099. In 2001, an anonymous person sold a pair of 100-plus-year-old jeans to Levi Strauss & Co. for $46,532.

Despite these numbers, Brit has yet to find a piece that approaches the pinnacle of the vintage market. In the summer of 2008, an eBay seller going by “Burgman” auctioned a pair of circa-1890s, candle-wax-encrusted Levi's that he claimed were found in a mine in California's Mojave Desert. On July 30, the bidding closed at $36,099. In 2001, an anonymous person sold a pair of 100-plus-year-old jeans, discovered in a Nevada mining town, on eBay through Butterfields, a San Francisco based┬áauction house. The jeans were purchased by their original manufacturer, Levi Strauss & Co., for $46,532. With stakes this high, Brit isn't eager to reveal his hunting grounds, but I'd arranged to spend a week with him on what he calls a “denim safari” and had met up with him at his warehouse, in Durango, Colorado. He was in good spirits; the day before, a couple of designers from Dickies had visited and made a substantial purchase. The warehouse is a garage-like structure with overhead doors, chaotically stacked wall to wall and floor to ceiling with plastic crates of vintage clothes bearing cryptic labels that Brit himself can hardly understand. “I hide stuff from myself so I can't sell it right away,” he said. “It's a retirement plan.”

From the warehouse, we'd driven to Brit's home, on the outskirts of town along the Animas River. In the morning, he said goodbye to his wife of four years, Kelly, and their three-year-old son, Zealand. Brit loaded a barebones collection of camping gear into the back of his Toyota Tundra and we headed west toward the Great Basin, between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada. “There's a chance we won't find anything out there,” he warned, “but it's the best place to be if you want to find something that's going to shake up the world.”

Late the following morning, we'd rolled into Modena, Utah, a once-thriving railroad community reduced by time to little more than a ghost town. The bank, hotel, and bars were all closed and permanently shuttered. The only sign of life was a middle-aged woman in a sedan who was sorting mail she'd pulled from a P.O. box. Brit's intuition suggested, correctly, that this woman lived on an old ranch, and he stepped out of his truck to make the somewhat preposterous suggestion that she let him dig through her closets and attics. Earlier, Brit had complained that the rain was a detriment to this particular approach. “People associate storms with strangers and trouble,” he said.

If the storm didn't scare her off, I was thinking, Brit's clothing might. He was wearing an olive-green 1940s canvas hunting vest, oversize 1950s fatigue pants, beat-to-hell leather boots of indeterminate age, and a white henley-style shirt from the 1920s. He explained to the woman that he pays good money for the sorts of things he was wearing and that it's not uncommon for him to fork over a thousand dollars for a piece that most people wouldn't even give to the Salvation Army.

“You know how kids nowadays buy jeans that are faded and full of holes?” he asked her. “Well, clients rely on guys like me to find things for design inspiration.” The woman looked at Brit as if he were asking her to strip right then and there, and she said that we better talk to her husband, Mike, about eight miles up the canyon. “But wait an hour,” she said. “He's dealing with a lion right now.”

Brit Eaton's path into the vintage-denim business was as circuitous as the occupation itself. The son of an investment banker and a mother with an interest in archaeology, he was born in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1970 and raised in a home dating back to the 18th century. His mother, Landis, believes that Brit inherited “the looking-for-things genes” from her.┬áDuring spring-cleaning season, she would strap him into a car seat and drive around to see what their neighbors had put out on the curb. “He never liked to wear anything but old stuff, and he was always an entrepreneur,” she says. As a kid, he sold pumpkins and lemonade at a roadside stand, and when he got a little older he tried expanding his product line to include lead toy soldiers that he produced with a Bunsen burner and a hand-casting mold. He remembers taking some of his product to a local Kmart in an unsuccessful bid to broker a wholesale contract.

Vintage Jeans

The Levi Strauss & Co. Archives contains  dating back to 1879, and shows the evolution of the iconic blue jean.

The Levi Strauss & Co. Archives contains┬á┬ádating back to 1879, and shows the evolution of the iconic blue jean. In 1988, Brit enrolled at Rollins College, in Winter Park, Florida. He spent his junior year in a semester-at-sea program that took him around the world, and the journey left him with him a deep wanderlust. After graduating, in 1992, he shipped an old Harley-Davidson to Rotterdam, Holland, thinking he'd tour Europe on two wheels. He rode the bike up to Norway, where he sold it for twice what he'd paid. Brit knew a solid business opportunity when he saw one, so he returned to the U.S. and escorted three more Harleys to Europe in 1993. He might have stayed in the motorcycle-import-export business if he hadn't gone to a party one night in Princeton, fallen into a window well, and broken a few ribs. “That made it pretty much impossible to kick-start old bikes,” he says.

Over the next few years, he racked up an impressive roamer's r├ęsum├ę: He was thrown in jail in Greece; drove a cab in Madison, Wisconsin; created and sold T-shirts at Grateful Dead concerts; sold ice cream on nudist beaches in Holland; got caught up in a multilevel marketing scheme in Florida; and worked for a company that organized trekking expeditions for Americans traveling in Europe. In early 1997, he took a job working on a swordfish long-liner out of Puerto Rico. He was confined to his quarters for insubordination, but the trip had a positive outcome. A fishing captain from another boat mentioned to Brit that his mother worked for an import-export agent who had a 1,000-pound, compression-packed bale of used Levi's in a Florida warehouse. It reminded Brit of something he'd heard a few years before, when a Norwegian Harley-Davidson customer suggested he import vintage Levi's along with bikes.

“Jeans have their own language,” he said. “It takes a while to figure it out.”

Brit returned to Florida in April 1997 and bought the bale for $750, then took it to a home where he was staying in Fort Lauderdale. When he cut the bale's straps, it exploded into a room-size pile of denim that his friends called Mount Levi. “Those jeans were in horrible shape,” Brit recalls. “Full of holes, ripped up.” Rather than ship them overseas, he spent his nights patching the jeans and his days trying to sell them at flea markets, three pairs for $10. Profits were skimpy. “It was absolutely the lowest point of my life,” he says.

But Brit noticed something unusual at the flea markets. Some vintage dealers would inspect his stacks of jeans and excitedly pluck out individual pairs for purchase regardless of condition. That's when Brit began to learn about big E's and little e's. Before 1971, Levi's jeans had an uppercase E printed on the tab sewn into the rear right pocket. After 1971, the company switched it to lowercase. In a general sense, a pair of Levi's is considered vintage when it has a big E, and these are much more valuable in the eyes of connoisseurs. (Vintage big E's are unrelated to Levi's premium Capital E line.) Brit learned about dozens of such categories for different brands, including classifications exclusive to the earliest types of jeans. He educated himself in the nuances of rivets, stitching, denim types, labels, and suspender buttons. “Jeans have their own language,” he said. “It takes a while to figure it out.”

Levi's is easily the most deep-pocketed consumer of vintage jeans. The company's historian, Lynn Downey, a self-described “obsessed vintage lunatic,” explained that Levi Strauss effectively invented “jeans” when he began putting rivets into the seams of denim pants in 1873. In 1906, the company's four-story warehouse burned down after the great San Francisco earthquake, destroying their inventory. Currently, is from 1879. “Levi's has produced items that I've never seen,” she said. This is a problem because vintage clothes represent the history of fashion and also mark the future. “Levi's designers are the primary users of our archives,” she said. In 1996, the company launched its Levi's Vintage Clothing line, featuring replicas of recovered pieces. Brit has conducted a few deals with Downey, and he refers to her type of high-dollar denim as “big game.”

Because Levi's didn't start selling jeans in the eastern U.S. until after World War II, there was an inherent limit to what could be found there. So in August 1997, Brit loaded his Jeep and migrated to Durango, Colorado. He began traveling up and down the Rocky Mountains until he knew the location and hours of just about every small-town thrift shop where someone might unknowingly drop off an item of surprising rarity and value. He would buy pickup loads of clothing at Goodwill prices and then sort out the more valuable items for shipment to his growing clientele of domestic and international vintage-clothing dealers. Jeans remained his passion, but he also developed an eye for other items that would get snapped up by savvy shoppers and Wild West enthusiasts: canvas work clothes, concho belts, biker jackets, hand-tooled cowboy boots, decorative saddle blankets, antique fur coats, riding chaps, cowboy hats, army surplus, and even homemade apparel.

Perhaps the most important thing Brit learned while hunting vintage clothes in thrift shops is that thrift shops are not the best places for guys like him to hunt vintage clothes. He didn't want the things that a person had recently quit wearing and donated; rather, he wanted the things that a person's great-grandfather had quit wearing and tossed into a dusty corner on a homestead, where it was forgotten about for a few generations. “I used to walk into a good thrift shop and my palms would get sweaty,” Brit told me. “And then one day I couldn't get excited by thrift shops. It's like I used to enjoy firecrackers, but now it takes dynamite to get me high.”

Finding a $40,000 pair of jeans requires luck and daring, but, most important, it requires leads. Brit collects leads while talking to people in bars, caf├ęs, hotels, gas stations, and antique shops. Good leads include the phone numbers of multigenerational ranch families, addresses of small-town historical societies, favorite saloons of modern-day miners, and even descriptions of landmarks leading to the properties of crazy old hermits who live up in the hills with collections of junk and arsenals of weapons.

As he follows these tips, Brit sometimes stumbles into a series of unusual events that cascade along for days. Before we even made it to the Meathook Ranch, where the lion had been trapped inside a fence, we had stopped in western Utah to visit the home of a retiree named Theo who spends his days tinkering with a vast collection of antique steam-engine tractors and compressors. Brit suspected that there might just be some old denim mixed in with all that old iron.

Theo was skeptical. “If it had been around that long, I would have sopped up some grease with it by now,” he said. His comment reminded me of something Brit had told me earlier: “My number-one rule in this business is to never believe anything I hear. The more someone tells me they don't have anything, the more I know they do.” Sure enough, Brit reached beneath a leaky outdoor spigot and picked up a small-game item that I would become very jealous of. It was a black T-shirt with macbeth printed on the front in an ominous font, and it resembled the faux-faded, distressed T-shirts that college freshmen buy at Urban Outfitters. Except this shirt's fading had happened thanks to endless doses of sun and occasional spurts of water, so it was infinitely cooler. Clutching the ten bucks that Brit gave him, Theo was beginning to agree. “It was all just rags to me,” he said. “Not no more!”

We spent much of the next day at the Meathook Ranch, where Mike the rancher segued seamlessly between searching for the lion and telling stretchers. “My grandfather didn't buy this ranch,” he bragged. “He just paid the outlaws and murderers who were living here to move along.” As we walked around, Mike pointed to various places where he'd allegedly killed 250 lions over the years. Brit scurried behind us like an unleashed dog, prying and poking into every trash pile, junked car, corral, smokehouse, and outhouse. After an hour of searching, he realized that the good stuff was long gone, having met its usual fate over the years in burning barrels and county dumps. “I was dying to get in here,” he whispered in my ear. “Now I'm dying to get outta here.”

When we finally shook free of the Meathook, we stumbled into a coyote trapper outside Modena whose trailer home fronted a collection of ramshackle log cabins. Right away, I saw the waistband of a pair of jeans stuffed between two cabin logs as chinking a common frontier use for old rags. The jeans had a buckle and straps riveted into the waistband in the back. Known as “bucklebacks,” such work pants were prevalent from the earliest days of jeans until about 1940.

We were on the right track. We crawled down into a root cellar and found banks of shelves still stocked with the fractured remains of canning jars. An ancient shirt was wedged into a doorjamb, but it turned to powder when Brit tried to carefully pull it free. When I creaked open the door of a neighboring cellar, I was greeted by the unmistakable snicker of a rattlesnake. I eased the door shut and remembered a story Brit had told me about the time he crawled into a mine and heard the hissing sound of a snake coming from the vicinity of his crotch. He retreated from the serpent with a mad dash while an excruciating burning sensation spread across his groin. Once outside, he realized that he'd actually been “bitten” by a canister of pepper spray he'd pocketed in order to defend himself against cave-dwelling beasts.

After Modena, Brit swore me to secrecy about the places we'd be visiting in “the vintage happy-hunting grounds.” We were on our way to visit a man I'll call Cowboy, who lived on the outskirts of a small mining town whose claim to fame is that, during its infancy, 75 citizens died in gunfights before a single person died of natural causes. Brit wanted to question Cowboy about a rumor he'd heard from the man's ex-wife that involved a mysterious building full of 1920s clothing.

At one stop, a man screamed “What's going on out here?!” in a voice that would have made John Wayne soil his pants. He was toting a shotgun, and he detained us at gunpoint while shouting commands.

“Cowboy is six-four and weighs 270 pounds,” said Brit. “He's a Korean War vet and a mountain man and, well, basically a hobo junk collector.” We found Cowboy at the center of the vast, moatlike collection of junked cars he uses as a security barrier around a small refuge of trashed camping trailers. His specific location inside an aluminum motor home was betrayed by a rising column of smoke out front where a pot of coffee was resting on a Weber grill packed full of smoldering sagebrush. Cowboy was passed out, his head propped on a stack of rags near an open window. Brit yelled inside to wake him, which startled the hell out of the man. He was drunk, or seemed to be, and he ranted and raved for a few minutes while expressing an intense lack of interest in talking about old clothes.

Brit and I drove into┬átown and parked in front of the diner where Cowboy gets his mail. We went inside and took a seat next to Uncle Teddy, a man in his seventies with a severe comb-over hairstyle. Brit introduced Uncle Teddy as someone who'd once sold him a buffalo-hide jacket. As they talked, Brit made the mistake of dropping the name of his associate, Cowboy. “He wouldn't make a pimple on a cowboy's ass,” said Uncle Teddy. Then he told us that Cowboy had recently been prosecuted for stealing another man's outhouse.

“What was so special about the outhouse?” I asked.

“What was special is that it didn't belong to Cowboy,” said Uncle Teddy.

We had just enough daylight for one more lead, and we headed to a mining camp occupied by an old man who was sacked out in another trailer. It was getting dark. There was no immediate reply when Brit honked his truck's horn and rapped on the door, but a frantically barking dog suggested that someone was around. After about 15 minutes, the man revealed himself by kicking open the trailer door from the inside. He had a long white beard and screamed “What's going on out here?!” in a voice that would have made John Wayne soil his pants. He was toting a shotgun, and he detained us at gunpoint while shouting indecipherable commands. It took a few moments for us to realize that he was stone deaf. Brit started yelling, “We'll never come back!” while we walked backwards with our hands in the air and then eased into the truck and sped off.

We settled into a bar that I'll call the Peephole and had a couple of shots to toast that the man hadn't pulled the trigger. When I lifted my third vodka, an hour later, my hand was still shaking. Brit was at the end of the bar talking to a drunken man who was covered in coal ash and wearing a denim chore coat. “This guy's got great leads,” he said.

The leads from the peephole kept us busy for a couple more days, though they didn't produce any exciting finds beyond a human leg bone that I plucked from a hole in the ground after being directed to the location by a local landowner. The waistband from the buckleback jeans outside Modena was the closest we'd come to a big-game find, though the back of the truck continued to pile up with small-game items that might fetch $10 or $50 or $200. In addition to Theo's macbeth T-shirt, we had a stack of saddle blankets, assorted western-style button-up shirts, a pair of 1970s corduroy pants, a beat-up piece of Filson luggage, a Victorian-era women's coat made of velvet, a homemade coat rack of welded horseshoes and fencing staples, a leather rifle scabbard, old riding chaps, assorted trucker's hats, and a pair of cowboy boots that were so stiff with age, they felt bronzed. (Brit soaks leather goods back to life in neat's-foot oil, which he buys by the drum.)

The underside was still blue, like the color on the knees of a pair of 501's when they're finally ready to give out. The denim crackled as it unfurled, and the bleached spot spread in a tie-dye pattern. I checked the label: J.C. PENNEY.

It was better stuff than you're going to see in 90 percent of college-town secondhand stores, but Brit was hardly impressed; in fact, he was growing increasingly annoyed over our inability to make a major score. He likes to describe his occupation as equal parts Antiques Roadshow and The Crocodile Hunter, but I was beginning to see traces of the Tasmanian Devil creeping into the mix. I'd been marking my notebook every time we went into a building (I registered more than 40 marks the first day), but now Brit was flying through structures with such rapidity that I hardly had time to pull it out. Rather than walking around the perimeter of a 30-foot-deep chasm in the center of an abandoned mill, Brit went over it by trotting along a partially rotten six-inch beam, his arms flailing out to his sides for balance. Several times I watched him pull himself up through holes in rotten ceilings only to bust through in a shower of pigeon shit and dust. One time, blasting down a dirt road, I looked at his truck's speedometer and saw he was driving three times the posted speed limit while packing his mouth with carrots and bread washed down with a Starbucks Frappuccino.

The numbing speed of our travel was punctuated by a few short moments of crystalline excitement. On our last full day in the field, we ran into a farm kid and his pack of hunting dogs in a wide irrigated valley bordered by rugged, chalk-white mountains. He said it'd be OK to poke around for old clothes in a chain of abandoned farm buildings scattered along the river to the north. Brit pored over most of the buildings, leaving his truck running outside and wielding his flashlight in a way that reminded me of an FBI agent conducting a drug raid. Instead of yelling “Police!” he constantly shouted “Snakes!” in an effort to scare off rattlers.But there was one old house where Brit slowed his pace and came to a complete stop. When I stepped inside the kitchen door, I could see why. It seemed as though someone had wandered off decades ago, leaving behind evidence of a very simple life. Mice-gnawed food crates were scattered about. A cupboard contained the sopping-wet pages of a novel published in 1918. A woodstove and chimney stood against the wall. In a corner by the door was an old pile of clothing that had rotted into a dirt-like mound. I walked into the main room and was startled when a large raptor dropped down from a rafter and, with a pump of its wings, pushed itself out a window.

“Take a look in that second chimney,” Brit said. I noticed a single section of stovepipe poking through the living-room ceiling and attached to nothing but air. I peered upward into the pipe and was surprised I couldn't see sunlight. When my eyes adjusted to the dark, I let out a whoop. What I was seeing was unmistakable: Some bygone resident had grown weary of the cold drafts from the chimney and had plugged it with fabric. I climbed up to fetch it, but the roof was so decrepit that the chimney rolled off and landed outside in the tumbleweed. I raced outside and removed from the pipe a cylindrical wad of denim. The top of the ball was bleached white from the daily doses of sun that managed to peek inside. The underside was still blue, like the color on the knees of a pair of 501's when they're finally ready to give out. The denim crackled as it unfurled, and the bleached spot spread in a tie-dye pattern. I checked the label: J.C. PENNEY.

Brit said the pants might be from the 1940s or even earlier, a great find if it weren't for the size. I held them up to my waist, and the hems barely came down to my knees. They were made for a little boy. I was still holding the jeans as we walked back toward the truck, and I couldn't help but wonder about the slow line of circumstances that might have played out inside that house. A couple of times I looked over my shoulder, irrationally expecting to see some poor little kid off in the sagebrush wearing nothing but his underwear. I found myself thinking that this family might've liked that their old clothes were actually worth something in this day and age. I recalled something from just a few days before, when Brit was negotiating with a rancher's wife over a cowboy hat that Brit had found in a tenantless house on her property. He made an offer for the hat, and after accepting the price, the rancher's wife noted that it had belonged to her husband's dead father.

“I shouldn't take the hat then,” Brit said. “He might be upset.”

The woman silently compared the price of her husband's anger with the price of the hat. Apparently, the hat was worth more.

“Don't worry,” she said. “You'll be long gone by the time he gets home.”