The Unlikely ASMR Hero of… Camp Stoves?

Our writer has a man crush on a Utah cook-stove inventor named Steve Despain, and it’s easy to see why. Using creative design, smart marketing, and YouTube star turns, he’s brought glamour to the humblest little workhorse in the outdoors.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

“Are you watching porn?”

It’s the middle of the night. My wife lifts the edge of her sleep mask and looks at me, my face lit by a glowing iPhone. Caught in the act.

Luckily, she’s open-minded about this sort of thing. “So what are you into?” she asks, leaning over to take a look.

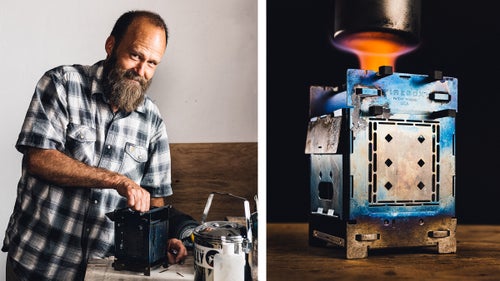

I show her. There’s a bearded man in a plaid shirt pan-frying trout fillets over a small wood-burning camp stove. Behind him, a serene mountain lake reflects the surrounding peaks.

He is not alone. There is a dog.

She seems disappointed but unsurprised. She already knows the guy on the screen, because lately he’s been an obsession of mine.

To be honest, most outdoor videos don’t do it for me. Too many hairy bushcrafters, grim-visaged survivalists, perky trail hikers, or slick gearheads—all overenthusiastically documenting their recent trips and latest purchases. But these are different.

Steve Despain is proprietor of , a small Utah company that sells patented wood-burning stoves of his own design, plus assorted other premium-quality camping products, most of which you can see him using in hundreds of videos. His has more than 160,000 subscribers, and he racks up views in the tens of millions. He’s all over and , too.

Very little happens in his videos, but that’s probably why they cast such a spell. Steve drives or hikes to a dramatic destination—sometimes the desert, sometimes the mountains—either by himself or with his family. He makes camp and maybe fishes a little. Then the real action starts. Steve sets up his small stove, lights a fire, and cooks.

Over the years, he’s roasted whole chickens, grilled steaks, made pots of chili, and baked cakes—but the classic meals, the two he falls back on over and over, are either freshly caught trout with garlic and lemon, or eggs and bacon on a bed of hash browns.

It always looks delicious, and he always sighs over every bite, usually with a comment like “So good.”

Steve is a laconic presence on-screen. He doesn’t go in for the nonstop narration typical of these kinds of videos. Instead, he invites you to simply watch what he’s doing. He adds occasional explanations or bits of advice as the need arises. He speaks in a near whisper. The effect is calming, intimate.

Each video is different but always the same, a variation on a theme, like a Bach cantata. For example, he punctuates most outings with a sequence at dawn where he quietly boils water and makes coffee. He grinds the beans on the spot with a portable grinder he sells on his website.

I cannot overstate how weirdly restorative I find Steve’s videos, especially after a stressful day. Apparently, I’m not alone. There are tens of thousands of comments on his YouTube channel, many like this:

I very rarely comment on videos but I just had to. I’m a 21 year old college student who is a typical millennial. Heavy use of social media, consumer of material goods … and never have I watched and felt more happiness and peace than when I watched this video.

As sales tools, his videos run the risk of doing more soothing than selling. Commenters began comparing them to the purportedly therapeutic ASMR videos that have been trending on YouTube lately. ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) is the scalp-tingling reaction that people claim to have to close-ups of somebody brushing their hair or crinkling paper or whispering softly. Steve’s reassuring demeanor reminds some of his followers of the late Bob Ross, the PBS painting instructor and an ironic cult hero of the ASMR crowd.

At first, Steve wasn’t sure if this was a compliment or not—Ross is a mildly ridiculous figure, the king of kitsch—but he’s decided to embrace the association. He now attaches the #ASMR hashtag to some of his new posts.

ASMR doesn’t work on me, but Steve’s videos are definitely my personal lava lamp. They’re mesmerizing, transporting—they instantly take me out of the city, where people work late and eat takeout over their kitchen sinks, and deliver me to the mountains, where a pan of fish is popping and sizzling over red coals.

That Steve seems to be doing what he loves—camping, fishing, cooking, being with his dogs and family—while also making a living at it only makes the videos even more inspirational.

The gear he sells is nice, too. I’ve gone online and bought a lot of it in the past few years. At the heart of the product line are Steve’s small, beautifully designed wood-burning stoves, ingeniously hinged so that they fold flat when not in use. I own several.

The original car-camping model, the , sells for 60 bucks. The tiny, ultralight backpacking version, (which can easily fit in a shirt pocket), costs less. They both also come in even lighter titanium versions. A network of perforations in the large stove’s 18-gauge stainless-steel walls supplies air, directs combustible gases, and focuses the heat, all of which helps generate higher temperatures than lighter competitors and mitigates steel warping, the primary problem with other wood-burning stoves. The things easily run on the broken bits of wood and twigs that other campers ignore.

Over the past nine years, the company claims to have sold more than 70,000 stoves, with almost no paid advertising, at prices ranging from $50 for the stainless-steel Nano to $150 for the all-titanium G2. Most of that time, they weren’t available on Amazon (and few Firebox products ), and you won’t find Firebox stuff in major retail outlets like Cabela’s or REI, either. He markets the gear himself on YouTube and Instagram and Facebook, and sells the vast majority through the website.

Last year, Steve sold roughly 12,000 stoves, along with pots, pans, and other camping items. He grossed more than $1.5 million and had to add a fourth employee to help pack and ship. He has no partners and no debt, and just paid cash for a new warehouse-cum-office. Not bad for someone who barely finished high school.

Steve lives in a perfect feedback loop. His love of the outdoors fuels his business, and the business allows him to spend an enviable amount of time outdoors. He’s not just selling stoves. He’s selling a lifestyle: one that’s slower, promotes a less-is-more ethos, and encourages a simpler, more authentic experience of nature. I buy his gear and try to use it the way I see him use it. I buy into what I see as the Firebox philosophy, a life-altering Weltanschauung. If I follow his simple instructions and use his gear, I will become happier. Calmer. More Steve-like.

My fascination with Steve is a source of endless ribbing from my family, not without justification. In the car or at dinner, I interject an observation of Steve’s that I consider on point; eyes roll. They are over it. Lately, I’ve been forced to admit that maybe my wife is right. The videos are like porn for me—an escape, a fake experience, a substitute for life.

The solution seems obvious. I need the real thing.

Driving south from Salt Lake City, I’m nervous about meeting Steve in person.

He lives in Utah’s Sanpete Valley, an agricultural swath between the San Pitch mountains to the west and the Wasatch Plateau to the east. The landscape is studded with scores of long white barns. Turns out they’re packed with turkeys. This part of Utah isn’t just Firebox Steve country. It’s also the turkey-ranching capital of the state.

I’ve brought a fly rod, waders, and not much else. The plan is to head for the mountains and go camping. “I really want to catch a fish and cook it for you,” Steve texted me just before I left. “That’s the iconic Firebox meal.”

All this time, I’d been thinking of Steve as a brawny Paul Bunyan with a frying pan. But when we shake hands outside his house soon after I pull up, I discover that he’s no bigger than I am—which is to say, average. I also imagined Steve as the strong, silent type, someone Sam Shepard might have played. Instead, I find myself facing a garrulous, funny, slightly frazzled 51-year-old in a plaid shirt and sandals, trying to feed a bottle of milk to a baby goat. He and his wife, Jessica, share their split-level house with his father, three kids, four cats, two dogs, assorted chickens, and two goats.

The goats are an interesting addition. Steve has to find new gimmicks to satisfy YouTube’s implacable algorithms, which require constant injections of fresh, attention-grabbing content. Untested destinations, surprising meals, unexpected supporting characters, and goats—Steve tries them all. He recently posted videos filmed on a beach in Hawaii during a vacation with his wife. In 2018, he slow-roasted a hunk of beef for seven hours, and the video got 5.6 million views. Steve’s two dogs are audience favorites. His growing kids draw positive comments, as do his parenting skills. Now he’s training baby goats to join the troupe as pets and pack animals—and a new source of comic relief.

I buy into what I see as the Firebox philosophy, a life-altering Weltanschauung. If I follow his simple instructions and use his gear, I will become happier. Calmer. More Steve-like.

Steve loves to tinker, so his home has a Rube Goldberg vibe. He repurposed a bike shed into a goat stable; he turned one side of the house into a movie screen for cartoons, beamed from an outdoor video projector. His whole family roasts hot dogs in a fire pit made from the rusted remains of an industrial clothes dryer.

Steve is a former car mechanic and an unrepentant motorhead. For his automotively inclined followers, the videos feature various interesting vehicles that he collects and restores. I recognize the 1986 VW Vanagon in the driveway, along with the 2003 white Toyota Tundra. Both appear in his camping videos. I ask about the 1997 Toyota T100 with a diesel upgrade, a YouTube fan favorite. It’s in the shop.

Steve has joined the ranks of internet celebrities—he’s a figure who fans know intimately, or think they do. Encountering the trucks, the menagerie, the patient wife and towheaded kids—it’s like going to a New York diner and running into the cast of Seinfeld, strangely familiar and startling at the same time.

Earlier, when we were texting back and forth, the banter and conversation had come easily. Steve said this was one of the benefits of internet fame. “You can kind of see how we already have somewhat of a relationship because of you watching my videos. That’s how it is with the customers on my website. They already know me in a way. And I think of them as friends, because they are the ones making it all work.”

But fame can get a little weird. A cop recently pulled Steve over on an empty mountain road.

“You lost?” he asked.

“No,” Steve replied, wondering what on earth he’d done. “Why?”

The cop confessed: He’d recognized Steve’s T100. He just wanted an excuse to say hi. “I’ve watched all your videos!” he blurted.

I know the feeling.

The next morning, Steve pulls up in the Tundra, loaded with fishing rods, hammocks, packs, sleeping pads, down quilts, camp chairs—two of everything, including the dogs, Ash and Juniper. Also, a large cooler, a backup battery power supply (just in case), a compressor (you never know), a string of lights, a rooftop tent (if we decide to stay with the truck), and a box packed with cooking gear. I load my stuff and we head south. Our goal is to find a cluster of three mountain lakes, unfamiliar to Steve, that a local fishing guide assured him are full of fish but not people.

Steve’s videos tend to alternate between austere, minimalist solo treks and rambunctious truck-camping expeditions with family and friends. Some of his more abstemious followers scoff at the luxuriousness of his car-camping style.

“They say, ‘You took all that gear out there? That’s not survival!’” he laughs, nudging away the dogs, who keep poking their noses into the front seat for a better view. “I’m a believer in comfy camping. I like to be comfortable! Some people believe you should go out there with nothing but your BVDs and a pocketknife.”

But when Steve takes the pared-down route—as he does in classics like and —he puts most ultralight campers to shame. He carries a Nano, an anodized Firebox pan, a five-foot spinning rod, a rain poncho that doubles as a tarp, and that’s pretty much it. He brings a bit of food but no water, just a filter. He doesn’t bother with a tent. The dog carries his own chow in a saddle pack.

“For some people, camping is all about the hiking,” Steve says. “They love the workout, they love pushing themselves, they love getting a lot of miles in every day. For me it’s the destination. And part of enjoying the place for me is cooking.”

Steve is a bit of a foodie, as is his wife. They both worked at a restaurant in Park City for several years. Good food around the fire, in his view, is an essential part of the camping experience. But cooking seriously good meals over an unruly campfire is difficult. Steve’s stoves, however, are versatile enough to make it possible, even for backpackers—and they fit with the leave-no-trace ethic of modern campers.

“Fire is the key,” he explains as we pass a sign for Fish Lake National Forest. “Have you ever sat around a fire with someone you’ve known for years, but this particular night you learn so much more about them and become so much closer as friends? People are more themselves when they’re camping. If you really want to get to know someone, go backpacking with them.”

I recently read Harvard anthropologist Richard Wrangham’s . He more or less argues the same thing. “We humans are the cooking apes,” Wrangham writes, “the creatures of the flame.” I’m not saying Steve should be teaching anthropology at Harvard. But he did figure this out on his own.

We found the lakes, but the fishing was tough, with the rainbows and cutthroats we saw ignoring nearly everything we put in front of them. We set up camp above the third lake, a deep pond protected by a steep slope of boulders and scree that poured down to the water’s edge. We descended unsteadily with the dogs, but the best spots remained out of reach, blocked by rocks or fallen trees. We managed only four small fish between us, just enough for dinner.

Talking over the course of the day, I learned how Steve came to be a successful inventor, a small-business owner, and a YouTube star. I’d come for wilderness therapy but got a crash course in retail economics, with a surprising dash of bitterness about the obstacles he’d encountered along the way. Despite the happy ending, Steve’s success was hard-won, and the setbacks still sting.

He hated school. “I was a horrible student,” he says. “I just wasn’t capable of paying attention to something I wasn’t interested in, and if I was interested in something, I couldn’t think of anything else.” His dad was a high school shop teacher, and his parents encouraged his creative impulses, even when others didn’t. “I always felt smart,” he says. “But I felt like everybody else thought I was stupid.”

As a teenager, Steve could take a lawn mower apart and put it back together. He discovered that he had a talent for clearly visualizing mechanical solutions in his head. “I immediately realized that this could be valuable to me,” he says. But he had no idea how.

When he was 15, he joined the Boy Scouts and loved when they went on fishing and camping trips in the mountains. His scoutmaster used a small wood-burning stove, one he’d made himself, and taught the boys how to clean and skin fresh-caught trout a certain way, the way Steve does it now.

He skipped college and worked as a mechanic and construction laborer while trying to realize his dream of becoming an inventor. With no training in mechanical engineering, design, or programming, but an uncanny knack for making things, he created a new kind of bike rack, which he managed to license to Yakima, though it never went into production. Then he designed an adjustable trailer hitch, which he tried to manufacture and market himself. Young and ambitious, he borrowed money from his father, and the business failed.

For the next five years, Steve did restaurant work in Park City and snowboarded. But he also began looking at cooking and food prep as a new opportunity. He dreamed up elaborate decorative garnishes to accompany dishes, which helped earn him a promotion to sous chef.

He married, became a father, and launched more businesses—one produced designer sinks and other bathroom fixtures for high-end homes. Another involved growing herbs on an industrial scale to sell to restaurants. The decor company died during the housing crash in 2008, and the herb operation succumbed to back-to-back early frosts and a grasshopper infestation.

Steve admits he’s always been “a worrier.” His trials and false starts took their toll not only on his confidence but on his nerves. His greatest strength is his commitment to hard work. His greatest vulnerability is a tendency to conceal his anxiety, allowing it to eat away at him. One virtue of repeated failure, though, was that he and his wife learned how to manage with less. “We drove cars with 250,000 miles on them,” he says. They were survivors.

He viewed the camping-stove business as his last chance, a final, desperate Hail Mary pass. He had nothing after that.

The original Firebox stove, which debuted in 2011, was a masterpiece of design ingenuity. Hinged at all four corners, it opened with a flip of the wrist. It was elegant and sturdy, and produced an amazing amount of heat with very little smoke.

At his house, he’d showed me the outdoor graveyard where his early prototypes all lay in a heap, rusted and blackened—a twisted-metal monument to trial and error. But it turned out that having a great product didn’t guarantee sales. In fact, it made them harder to come by, because higher quality meant higher costs and higher prices. Steve’s early partners envisioned something inexpensive that could be sold in Walmart to survivalists and preppers. They wanted to ship stoves by the thousands and pocket millions as soon as possible.

Steve’s first stove was not the cheap product they had envisioned. And his timing couldn’t have been worse: The launch coincided with the appearance of a new generation of lighter and more efficient gas stoves, produced and heavily marketed by companies like Jetboil and MSR. Americans preferred gas camp stoves anyway. Steve’s invention was always going to be a tough sell.

The partners quarreled. The tension exacerbated Steve’s anxiety. He was miserable. He dreaded going into the office. Finally, he bought out the last remaining partner and ran the company alone. “I had faith in it,” he says. “I really believed it was going to work.”

The problem remained, though: finding customers. Other companies had big budgets for advertising and packaging. Steve didn’t. He couldn’t get his stove into high-end retail stores, and it was too expensive for Walmart.

So Steve did what he’d done his whole life: he found a work-around, a hack. Brick-and-mortar outlets may have had no space for him, but the internet had plenty. In 2011, Steve discovered YouTube and put up a few clumsy promotional videos. But it took a little longer for YouTube to discover Steve.

Watching Steve cook dinner is odd. I’d come to Utah to get a behind-the-scenes look at a Firebox Steve production, and now I’m a bit player in one of them. I feel like Buster Keaton in Sherlock Jr. when he jumps through the movie screen and ends up inside the silent film he’d been watching.

To shoot himself cooking, Steve uses his Samsung phone, a portable tripod, and a bulbous microphone. He rarely stops filming, which he says drives his wife nuts. He shoots the drive to the campsite. He shoots us fishing. He shoots himself making the entire dinner. He does so expertly, moving the tripod and changing the angle as the scene requires.

He didn’t do all this at first. His earliest videos are embarrassingly conventional, with Steve doing his best to deliver a standard pitch. Today he doesn’t seem to be hawking a product. He just is. Part of his secret sauce is that he hardly speaks. He learned this by watching other outdoor videos. “I could see that people were talking too much, which made me look at my videos more carefully. And while I do still have that urge to talk, and I do still talk, I end up cutting it out when I edit,” he says. “I’m like, ‘Gee, shut up dude. Just shut up.’”

As he prepares and cooks our fish, I recognize every aspect of the ritual—building the fire, chopping the garlic and onion, sliding the dehydrated hash browns into the pan, adding a splash of water, layering on the skinned fillets, and then covering everything to fry and steam at the same time.

After a while, I forget that he’s filming. He feeds a few more sticks into the stove. “In a sec, I’m gonna put water in here,” he says quietly. “The thermal mass will absorb all that heat.” I nod, but it’s hard to tell if he’s talking to me or the camera.

On YouTube and Instagram, it isn’t enough to put up a few good videos. You have to trigger the algorithms, which measure engagement and try to match content with a user’s past interests. The invisible rules put certain videos in front of users and bury others. To do that, you need something new every week, even every day. It’s relentless but effective.

And that’s the sum total of Steve’s sales strategy. Firebox Outdoors still has almost no marketing budget. Nearly all the stuff on his website—stoves, cutting boards, pots and pans, coffee-making gear, baking accessories, and dozens of other items—is shipped directly from his office-warehouse in Mount Pleasant, Utah. He doesn’t frequent retail shows, yet he sells all over the U.S. and world and has found robust markets in Japan and the Middle East. For now that’s enough.

As a teenager, Steve had a talent for clearly visualizing mechanical solutions in his head. “I immediately realized that this could be valuable to me,” he says. But he had no idea how.

His early partners wanted to grow the business quickly. But Steve is happy to go slow, keeping risk to a minimum. “I haven’t let go of living cheap,” he says. “I’m almost afraid of spending money. It feels dangerous.” His business goals remain modest: a decent living, financial security for his family, and a chance to enjoy the kind of outdoor life he’s known since he was a kid. That’s what drives him.

There’s a little Huck Finn in Steve, maybe a lot: the independent loner, the dropout. “I really value my freedom,” he says. After years of solitary toil and struggle, the Firebox stove turned his life around. His is not a macho success story. It’s a story of someone trying to live, protecting their own set of fragile values, and staying sane while doing it.

At the end of our time together, shortly before Steve dropped me at my motel, I asked one more question. My hands-down favorite video of his is a long, contemplative solo trip he took to a particularly beautiful spot in Utah’s Uinta Mountains—a lake at 11,000 feet, totally pristine, teeming with native brook trout. It’s a difficult overland drive followed by a long, exhausting hike.

In the clip, Steve spends two magical days there, catching fish (and eating a few) while capturing the changing light on the mountains, the thick, palpable silences, and the incredible stillness of the lake as the sun rises. I’ve watched it many times. It’s what hooked me on Firebox videos. But I never bookmarked it on YouTube, and recently I couldn’t find it. So I asked him about it.

Steve explained what happened. It’s his favorite place in the whole world, and he knew it was as close as he’d ever get to a perfect Firebox video, but he learned that a group of overzealous fans had teamed up to try to pinpoint the location, using information gleaned from the video itself. He was afraid he’d inadvertently given away his secret spot.

In one sense he was being selfish, but he also felt guilty. He didn’t want to be responsible for exposing a vulnerable, pristine site that couldn’t handle too many visitors. YouTube stars don’t usually take down their best videos. But Steve didn’t want to jeopardize a small, fragile part of his world, one he relied on for mental and creative sustenance.

He took it down.