Over the past week, the internet╠ř of a new Tesla e-bike conceptÔÇöa futuristic silhouette packed with electronic steering, autopilot technology, and a new approach to suspension. The first thing to know is that itÔÇÖs more moped than e-bike (it has no pedals). The second is that itÔÇÖs not actually from Tesla. The designer, Kendall Toerner, does not work for the company; he just used its name and logo to accompany the mock-ups. The third thing to know is that if it existed in real life, it wouldnÔÇÖt work.

ItÔÇÖs not that we donÔÇÖt have the technology for it yet. ToernerÔÇÖs ÔÇťModel BÔÇŁ is a lovely example of industrial design and offers╠řsome thought-provoking ideas about dashboards and sensor╠řadvancements. But itÔÇÖs╠řphysically impossible to execute. ThatÔÇÖs the bug: unless concepts suggest plausible solutions to real problems, theyÔÇÖre just doodles.

The central feature that people seem to be oohing and aahing over is the steering. Pretty much since the invention of the bicycle, steering has been a simple affair: the fork, which holds the front wheel, is situated in an articulating column attached to handlebars. You point the front wheel in the direction you want to go, lean╠řthe bike, and youÔÇÖre off. I may have missed something, but in over 30 years of riding, IÔÇÖve never heard anyone say, ÔÇťYÔÇÖknow, letÔÇÖs rethink this whole steering thing.ÔÇŁ

The Model B does that. The handlebars donÔÇÖt move, but when you push on them, sensors detect that╠řforce and tell the fork (which is still on an articulating column, mind you) to turn in the direction you want to go. So╠řriders would have to relearn how to steer. ThereÔÇÖs also a╠řmention of╠řautopilot, which is counterintuitive, because balance is key to successful riding.╠řIf the rig suddenly changes direction without warning, your ass is on the ground. Ask any equestrian.

This is ironic, given that cycling is an enduring symbol of things that become second nature once you learn them. As the saying goes: itÔÇÖs just like riding a bike. Except╠řin this case, itÔÇÖs not. This is territory, where a perfectly functional piece of analog technology is ruined by the unnecessary addition of a silicon chip.

But most of the reaction IÔÇÖve seen╠řhypes that steering feature, or it praises the equally dubious idea of putting suspension inside the wheels via struts between hub and rim╠řwithout regard to the fact that both are unworkable. (Assuming we found a material that would even allow it, a rim that deflects enough for the suspension-wheel idea to work would never securely hold a tire.)

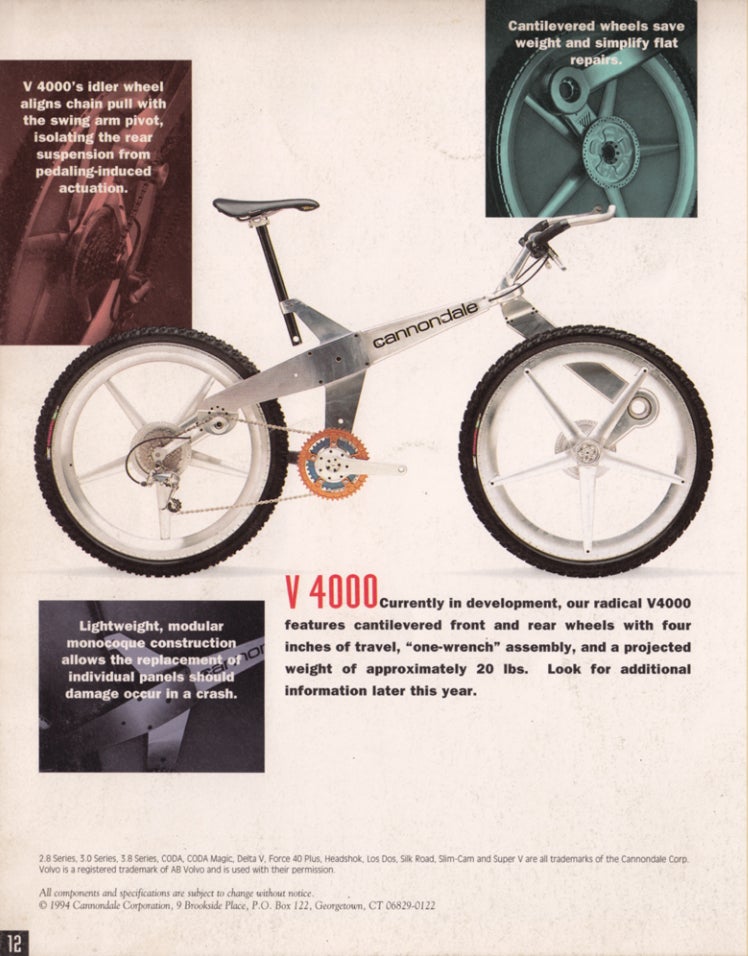

Totally unrealistic concept bikes are╠řnot unusual. In the mid-1990s, CannondaleÔÇÖs Alex Pong designed a now infamous carbon-fiber creature that replaced a road bikeÔÇÖs front wheel with an enclosed inline skate. The goal was to eliminate a major source of aerodynamic drag (the front wheel).╠řI give credit to Cannondale for actually building a╠ř╠řrather than just doing a CAD drawing. But as anyone who tried to ride it discovered, the small inline wheels were impossible to balance on. As╠řa solution for a problem, it was a dead end.

ThatÔÇÖs not to say that concept designs have no value. Another of PongÔÇÖs fanciful mid-nineties╠řcreations was a mountain bike with a mono-blade suspension fork, a concept that Cannondale turned into the not long after. And SpecializedÔÇÖs headquarters in Morgan Hill, California,╠řhas╠řa veritable gallery of one-off bikes from its longtime creative director, Robert Egger. TheyÔÇÖre each crazy in their own way, but in many you can see the lineage to actual products, like his Renegade FSR drop-bar suspension bike, which helped inspire the ╠řsystem on the Diverge and Roubaix lines.

There are things to like about the Model B. IÔÇÖm intrigued by the idea of pothole-sensing or stability-assistance technology. And the overall aesthetic is pretty slick. As Toerner notes in the , far more people see cars as status symbols than they do bicycles. Gorgeous urban e-bikes might help change that.

Concepts exist to get us talking and thinking. Sometimes╠řEgger uses his art to send a message, like the FUCI road bike that featured every single technology that is banned by .╠řAnd they should express ideas that technology canÔÇÖt yet realize, because that pushes technology forward. But what Egger gets is that concepts work best when they focus on a meaningful goal thatÔÇÖs tethered to reality. The Model B╠řfails on both accounts.

Where will the Model B go from here? Probably not to Tesla, even though Elon Musk about making a bike. Maybe it goes nowhere and╠řjust stalls as╠řthe╠řlatest fleeting obsession on╠řdesign blogs, which for some reason╠řresurfaced the Model B concept last month, even though it was created in January. It got people talking, which is fun. But it would be better if the possible future it envisioned was actually attainable.