’s Stockholm headquarters shares many of the same design elements you’ll find in the brand’s products: sleek lines, lots of glossy white, pops of the signature neon orange. Desks crammed with prototype helmets, goggles, and sunglasses line up beneath 20-foot-tall windows overlooking a quiet, trendy neighborhood in the Swedish capital. Miles of technical, rocky singletrack (“testing grounds,” as one engineer called them) wind around the city less than a ten-minute bike ride away. A silver espresso machine sits on a spare white bar in back, doling out the team’s frequent caffeine hits and the daily fika—a national ritual where everyone sits down together to share coffee and cake. If design reflects the identity of a company, as likes to say, then POC is classic Scandinavian efficiency.

Over the past decade, POC has established itself as the world leader in outdoor safety gear. The company launched in the winter of 2005–2006 with its . The lid, versions of which are still in the line today, was built to address what Ytterborn thought of as in the ski-racing helmets of his kids (ages five and six at the time). With soft earpieces, single-impact foam bodies, and easily dentable shells, most were about as effective as Styrofoam when it came to protecting a brain in a high-speed crash. A former racer himself, Ytterborn had watched as allowed athletes to go faster and higher and events—like the Winter X Games—became more demanding. Key safety accessories weren’t keeping up. “We needed to get into the most critical, demanding segment of the industry: for us, that was ski racing,” he says.

In 2006, after a young, little-known American ski racer named Julia Mancuso won giant slalom gold at that year’s Olympic Games wearing the slick Jetsons-esque hard-shell Orbic, the distinctive lids started appearing at ski hills and race courses throughout the United States. Four years later, POC would add—to that ski helmet, becoming the first company to use the design in active-sport gear.

Since then, POC has branched out of ski racing and entered the road and mountain bike markets while continuing to build a reputation for high-performance, innovative safety gear. In 2013, it released the first helmet with a when you crash. The following year, POC debuted mountain bike kits made with , a material that hardens upon impact, mimicking solid downhill armor without the stiffness or weight penalty. In 2015, POC launched smart helmets that speak with cars and know when the helmet needs to be replaced, as well as a prototype airbag vest for ski racers. Then, in 2016, POC announced a road bike kit with lights incorporated into the fabric as a way to ward off traffic. Since the end of 2014, POC has won dozens of awards, including , , and three Gear of the Show honors from ���ϳԹ���.

Now the Swedish brand is shifting its focus once again—toward psychology. “We wanted to study behavior: how people act in a certain situation and what their intuitions are,” says Ytterborn. In practice, that meant developing hard goods designed to influence how people—both the athletes and the people around them—think and act. POC’s (short for Attention Visibility Interaction Protection) is founded on that philosophy. Characterized by bright, blocky contrasting colors and safety tech like VPD foam and ICE emergency communication sensors, these helmets, jerseys, bibs, and sunglasses are designed with safety in mind. “,” says Ytterborn. “We took data like that and incorporated it into our road products.”

The road bike line likely holds the most potential. After all, staying safe as a ski racer or mountain biker usually comes down to an athlete’s choice: she has agency to push her limits or not. Road bikers’ safety, on the other hand, is at the whim of the several-ton missiles and their pilots with whom cyclists share the roads. To that effect, POC’s 2016 AID line was built with riders and drivers in mind. The commuting collection includes a handful of products that use digital technology. There’s the Corpora helmet, with a built-in accelerometer and a row of five LEDs on the back that get brighter when the wearer brakes. And POC partnered with another Swedish company, , to create a bike vest with a patch of blue and white lights printed on the back to boost the cyclist’s visibility. The Corpora is slated to go on sale this spring, while the vest will come out mid-July. “The technology is scalable, which enables us to build new functionalities on the same platform,” says Johan Weman, manager of digital business and partnerships at POC.

Of course, if you’re trying to keep riders safe on pavement, it helps to partner with the other side: a car company. So the little outdoor company focused on safety decided to work with a big automaker focused on safety: Volvo, whose Gothenburg headquarters are located about 310 miles to the southwest. The partnership falls under the POC Lab group, composed of five experts who provide input on safety designs. Chief among them on the road bike front is Magdalena Lindman, a technical expert in Volvo’s Traffic Safety Data Analysis branch. At Volvo, Lindman’s job is to analyze crash data, determine what went wrong, and then implement design changes to fix the problem. With POC, she offers insight into that data as well as feedback on how to improve riders’ safety. “The first order of business should be to make the rider more visible,” Lindman says.

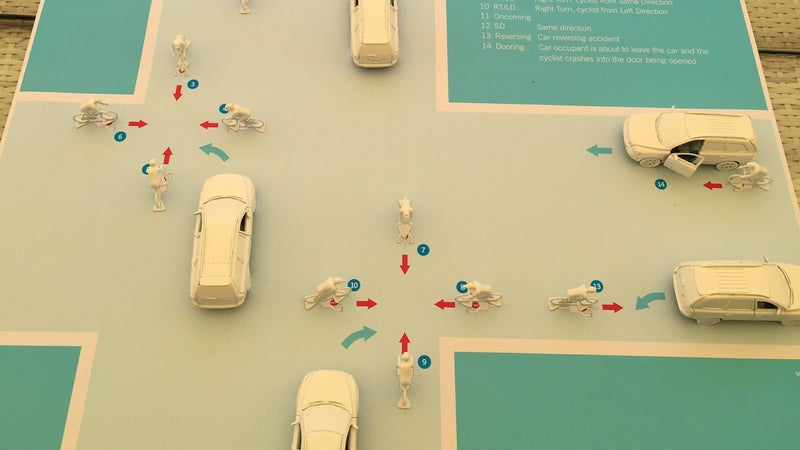

To that end, , emitting a signal when a driver got too close. That particular product was just a marketing stunt, but Weman said the technology exists to make something like that a reality for consumers. The brands are currently working on what they call the Map of Consequences (MOC)—basically an outline of all the dangers cyclists face on the roads and the most common crash situations. While it’s only a concept, the idea is that a POC helmet would be equipped with a device that would let a rider know when, say, a driver is about to open a door in her face by flashing lights in the front of the lid. “MOC is a way of finding out what’s important to work with and what can be done to fix the problem,” says Lindman.

First, POC will need to develop a sensor system to deliver this accurate, live feedback, and then finish some more basic designs, like a more efficient battery pack for the smart helmet. More functionality will require more energy, and Weman says he’s toying with the idea of adding solar panels to future versions of the Corpora. “It’s great proof that we’re looking at the right, real situations,” he says, before heading back to his desk, lined with prototypes.