LAST WINTER, I came home from a trip to Panama hosting a worm. The parasite, which invaded my left ankle while I was reporting a story, had been living in me for about two weeks, and had suddenly become quite active. It was white and tiny—about a half-millimeter long—and it left a meandering, pus-filled track that looked like a piece of angel-hair pasta trapped under my skin. I discovered the creature while in the shower and showed it to my wife.

“What do you think?” I asked, still in my towel, proudly holding out my ankle.

“It’s revolting,” she said. “What are you going to do about it?”

“I don’t know. Maybe nothing.”

“How do you know it won’t lay eggs in you, or migrate to another part of your body, like your brain?” she asked.

Decent questions. I went off to find answers, relying on that old, trustworthy medical source, the Web. I quickly found a site devoted to exotic skin maladies and diagnosed myself with “creeping eruption” caused by Ancylostoma braziliense, a hookworm that normally lives in dogs and cats but sometimes invades humans. The site featured photos of A. braziliense, blowups that revealed the creature to be a sort of Hollywood alien, eyeless and toothy, with a menacing black vortex of a mouth.

Was it gross? You bet. Was it dangerous? It seemed not. Humans are accidental, dead-end hosts for A. braziliense, noted eMedicine.com. The worm isn’t equipped to suck blood or lay eggs inside the intestines of humans—they can only do that in dogs and cats—so I probably wouldn’t suffer much harm.

I put off going to the doctor. Meanwhile, the worm wandered with great energy, sometimes covering three inches a day. But this was not the George W. Bush of parasites. Instead of pursuing a path relentlessly, it flip-flopped and crossed over its own tracks as if it were blind, which, of course, it was. It often ended up exactly where it started, and never once did it roam into the ample spaces beyond my greater ankle.

Before long, I had a raging skin infection. My ankle blew up to the size of a softball and leaked prolific amounts of worm juice, a syrupy yellow pus that was as slippery as slug slime. At first I tried to conceal the mess, but as I quickly learned, parasites don’t necessarily make you a pariah. They can also make you popular. People wanted to see the worm, and a few wanted to touch it. After someone in my office snapped a digital photo and e-mailed it around, news of the worm’s existence spread far and wide. Soon, old friends I hadn’t heard from in years were writing to ask if I had given it a name. (Never got around to it.) My four-year-old nephew gave a report about the parasite to his preschool class, in which he bragged, “My uncle has a worm in his ankle!”

The cachet was so sweet, I began to grow fond of my worm. Many people I know who work in the tropics—whether they’re missionaries, scientists, or gold miners—like to tell horror stories about the afflictions they’ve endured: scorpion stings, trench foot, dengue fever, vampire-bat attacks. As soon as I could, I told everyone I knew about my little hitchhiker, and the response was unanimous: None of them had ever had a worm under their skin. They were jealous.

The only people who failed to appreciate the worm were my wife, who thought I was crazy not to get rid of it, and her mother, who was convinced that it was contagious and rushed to our apartment the day after she heard about it and scrubbed the floors with bleach. To reassure her, I paid a visit to my physician, Dr. Blanche Leung, who gave me a prescription for albendazole, a medicine that, she said, would screw up the worm’s metabolism and kill it.

“Then what?” I asked glumly.

“Probably it’ll just decompose and get flushed out of your body,” Leung replied. But there was also a chance for one last act of gross-out theatrics—the worm might bolt for the exit, so to speak, in which case I should prepare for the sci-fi scenario of a live worm wriggling out of my mouth or one of my nostrils. I could only hope it would happen at a crowded dinner table, under a bright light.

WORMS REALLY aren’t funny, of course. They infect one-fifth of the world’s population, quietly sponging off their hosts. Tapeworms, for example, live in the gut and can grow up to 85 feet without calling much attention to themselves, aside from the fact that—being parasites—they steal your caloric supplies, kind of like a deadbeat neighbor tapping into your cable-TV line.

My hookworm was similarly nonlethal: A. braziliense lacks the necessary enzymes to bore deep into the human body, scientists believe. But hookworms in general are serious threats.

One species is called Necator americanus—”American killer” in Latin, so named for the damage it did in the American South after the Civil War. Necator and related hookworms have largely been eliminated from the U.S. and other industrialized nations, but they still thrive in underdeveloped countries where the climate is warm. Peter Hotez, chair of the microbiology and tropical-medicine department at George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., says hookworm infestation, then and now, is “a disease of poverty, a rural disease.”

The near-invisible larvae lurk in warm, moist soil or sand, infecting their host by penetrating the skin, usually through the soles of the feet. They travel through the bloodstream to the lungs, then they’re coughed up, swallowed, and wind up in the small intestine. There they suck blood, grow into adults, and produce massive amounts of eggs.

“The worm causes blood loss in the intestines,” says Hotez, who is developing a hookworm vaccine in partnership with the Sabin Vaccine Institute, in New Canaan, Connecticut. Health problems get particularly nasty, he says, when people harbor “a heavy load,” or between 40 and 160 worms. “When you lose enough blood, you get anemic, you experience fatigue,” Hotez explains. Communities where hookworm is prevalent tend to be economically disadvantaged, at least partly because of the debilitating effects.

The worms also have terrible impacts on children, in whom a heavy load can create protein and iron deficiencies that retard growth and intellectual development. In places where walking barefoot is common but indoor plumbing is not, it’s easy for kids to get infected. The eggs travel from the intestine to the ground and thrive as larvae in feces, which eventually get stepped on.

In the early 20th century, the hookworm plague in the U.S. was eradicated with help from a legendary public-health campaign led by John D. Rockefeller, the oil baron, in an effort that pounded home the virtues of sanitation. Hotez hopes to accomplish the same thing on a global scale with his vaccine, which is being heavily funded by another charitable industrialist, Bill Gates. The vaccine will be a two-stage antigen “cocktail” that triggers an immune response in the host. Clinical trials could start as early as next year.

“Hookworm is an international health problem of tremendous significance—some studies show that, in terms of numbers, only malaria causes more misery,” Hotez says. But because it’s primarily a Third World disease—and anti-worm vaccines and medications aren’t likely to make huge profits—the drug industry hasn’t paid much attention. “As with so many other diseases, there’s no incentive for a drug company to make a product, and for one reason: It doesn’t affect Americans.”

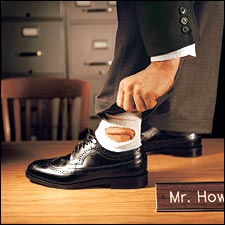

AFTER A THREE-DAY course of albendazole, I waited for the worm’s dramatic exit. And waited. But instead of leaving my body, the worm went AWOL. A week later, I was playing soccer when my ankle started to feel weird. I took off my shoe at halftime, and there it was, squiggling angrily, as if I’d awakened it. The albendazole nauseated me and made my urine smell like sulfur, but I suffered through another round of it. And again, the worm vanished, but resurfaced when I finished the pills.

It appeared I had an indestructible parasite, which didn’t bother me too much as long as it stayed in my ankle. My wife, however, was dying inside. “I can’t stand it,” she confessed. “I’ve never found anything in my life so disgusting. Please, get rid of it. I’m begging you.”

A Brazilian friend told me he knew exactly what to do. “Don’t bother with doctors,” he said. “This is a very common problem in Brazil. Just get a needle and some thread and sew a circle around the worm. Pretty soon he will have nowhere to go, and he’ll pop out of the skin all by himself!”

Ultimately, I went to see Dr. Kevin Cahill, a famous tropical-medicine specialist and president of the Center for International Health and Cooperation, in New York City. In 1959, Cahill, now 68, worked in the slums of Calcutta with Mother Teresa, and he later became known for his relief work in war zones like Somalia, Sudan, and Nicaragua. Today he treats seemingly all the foreign correspondents and diplomats in Manhattan. His office on Fifth Avenue is decorated with poison-tipped arrows and an antelope-skin quiver from a pygmy tribe in Central Africa, plus 16 of the 30 books he’s written on relief operations and tropical medicine. When Cahill himself appeared, he looked like a ship’s surgeon in Her Majesty’s Navy— small, cherubic cheeks, caterpillar eyebrows, and a dollop of white hair combed à la Horatio Hornblower.

“So you’ve got a worm,” he said cheerily. “Let’s see.” I pulled up my pant leg.

“Ha!” Cahill said. “There it is.” He cradled my foot in his hands and squinted. “Where’d you get it?”

“Panama,” I said.

“Of course, Panama. Good place to get one. You can put your shoe back on.” The doctor seemed less than impressed. I felt disappointed.

“Do you see this a lot?” I asked.

“Just saw an entire wedding party infected with creeping eruption last week. Twelve people. The ceremony was on a beach in India.” He patted his butt. “They were sitting in the sand, where the worm larvae like to hide.”

“Is it dangerous?”

“Creeping eruption itself is not. But there’s always the chance that what you have is not creeping eruption but a condition called visceral larva migrans, caused by a similar worm. In that case, the parasite wanders through the body, looking for a home. It doesn’t find it in the bowels, it doesn’t find it under the skin. It wanders and wanders”—I thought I saw him smile, relishing the details—”until it reaches, very often, the back of the eyeball.”

I smiled wanly, feeling much less brave.

“A few times a year, I get a call from some surgeon who just removed a patient’s eye, and instead of finding what he expected to find—cancer, say—there’s a worm.”

“I see.”

“I can offer you a remedy,” he said. “A stronger parasiticide called thiabendazole. The tablets will make you sick, but they’ll do the job. Or you can see if the worm goes away on its own.”

I chose the medicine and began taking it that night, though I was on my way to a wedding in San Francisco. There would be partying and merriment all weekend, but I would lie in my hotel room, blurry-eyed and dizzy, writhing in agony as the chemicals coursed through my body and burned into my intestines, which felt as if they were dissolving in flames.

THE WORM FINALLY went away, after living inside me for five weeks. As soon as I felt the effects of the thiabendazole, I knew its run was over. By this time, all the novelty had worn off, and I was eager to see my ankle return to normal size.

Six months later, though, people still ask me, “What happened to the worm? Do you still have it?” And when I say no, some of them say, “Are you sure?”

In fact, I’m not.

Sometimes I feel a little tingle in my ankle and reach down to see if it’s what I think it is. Sometimes, if I’m running low on caffeine or if things look fuzzy through my smudged glasses, a tremor passes through me, and I have visions of a surgeon holding up an eyeball, calling out to the interns, “Look at this!”

“Would you feel a worm migrating through your body?” I asked Cahill during an anxiety-induced follow-up visit.

“I don’t think so,” he chuckled. For a second he reconsidered. “Well, you might.” Then he thought about it again and said, “No, it’s definitely too small.”

Not long after, I called Peter Hotez on my cell phone as I was driving on I-684 in New York. He happened to be meeting with—of all people—Adan Rios, Panama’s ambassador to the U.S. for health and technology, and he put me on a speakerphone so we could all talk. I pulled into a rest area.

“Where did you get your worm?” the ambassador asked. I told him my best guess: a fancy resort on the Pacific coast, where I’d gone barefoot on the beach.

“Oh, I know that place,” he said. “Excellent fishing there. Quite beautiful.”

“What can I help you with?” Hotez broke in. When I told him about my fears, he didn’t sound amused. “You know,” he said, “there’s a condition called worm psychosis.”

“Really?” I rolled up my car window to hear him better.

“Yes,” he continued. “People think they’re infested with worms. In fact, they think their bodies are literally overflowing with them.”

“And are they?” I asked, starting to get his point. “No. It’s all in their head.”

“Have you ever met these people?”

“Well, there aren’t many scientists out there who study worms, so I actually have worm groupies, people I correspond with, who e-mail me all the time. The interesting thing is, they’re not delusional in any other way. It’s just the worms. Sometimes they send me their worms, or what they think are their worms.”

“And what are they?”

“Nothing. Pieces of lint in a jar. It’s fascinating.”

I thanked Hotez, though at that moment I didn’t really feel thankful. The worm’s physical presence was gone—I truly believed that. But the creepy feeling—that sense of being inhabited—would always be with me. The worm was dead. Long live the worm.