MY FRIEND ROSS NEILL is looking grumpy, and I’m to blame. Five of us are about to get on a small fishing boat—Ross, me, his parents, and our guide—but we’ve just realized that we don’t have fishing licenses, so we’ll have to change our plans.

Profile of a Boy With Dwarfism

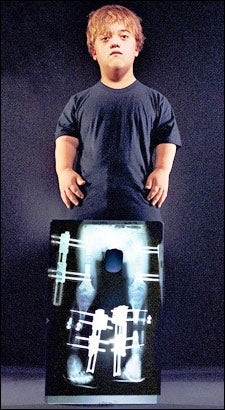

Ross in New York

Ross in New YorkProfile of a Boy With Dwarfism

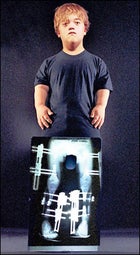

Ross with one of his many sets of X–rays

Ross with one of his many sets of X–raysWe’re staying together on Sanibel Island, Florida, and I should have made sure everybody bought licenses there this morning. We were running late, though, and I figured we could get them at our destination, an isolated waterfront town an hour to the north called Pineland. Alas, Neptune has been cruel. There are docks and boats and even a fishing lodge here, and the whole shebang faces a huge swath of inland salt water that’s teeming with redfish and snook. But there’s no bait shop.

I try not to look at Ross as the news sinks in that we’ll spend our first day (of two) exploring barrier islands, collecting seashells instead of throwing hooks. He’s 15, not 50. This does not represent an upgrade.

Our guide, Rogan White, the 25–year–old son of editor at large Randy Wayne White, tries to make the best of it, taking us several miles out to an island called Cayo Costa, where we hit the shore for a morning of, um, extreme beachcombing. Ross says “Goddammit!” when his feet get wet and is bored by a sign that says the island has a population of wild hogs. (Unless they come out and devour me, what good are they to him?) Rogan takes us to a tide line where there’s a long, thick band of unpicked shells, cheerfully declaring, “This beach is loaded.”

Ross isn’t buying it. While his mom and I go for a swim, he sits with his dad near scruffy undergrowth at the back of the beach, a blond, blue–eyed hermit crab huddled inside a Mariano Rivera T–shirt.

I have to wonder if something else is wrong. Ross and I are old outdoor buddies, and there’s usually more zest to his negativity. Later, I ask his parents—Tracey Harden and Michael Neill, a Manhattan couple—what’s up, and they confirm that his bad mood isn’t about the blown fishing day. The kid has more serious things on his mind: In a couple of weeks, he’s scheduled for a risky surgical procedure that has him terrified.

ROSS WAS BORN with a genetic condition called achondroplasia, a common form of dwarfism. Corrective surgery has been a defining part of his life, and right now two different things are going on. The operation coming up is a one–shot aimed at fixing his spine, which is curved badly enough that he walks with a painful–looking sway. His spinal canal is also narrowed, causing compression in the lumbar region because there’s not quite enough room inside for his spinal cord. This isn’t life–threatening, but his spine has to be repaired—opened up, fused, and braced with metal rods—or he could have problems with organ function as an adult.

In addition, Ross has been undergoing a series of elective surgeries for several years—he’ll have had four in all between the ages of seven and 17—that are designed to make him nearly a foot taller. This is called limb lengthening, and it’s controversial. Though the procedure has some mundane applications on non–dwarf patients—such as repairing old fractures that didn’t heal properly—it’s also used to increase stature, through a process that is expensive, painful, and protracted. For these and other reasons, advocacy groups like the National Organization of Short Statured Adults oppose the use of limb lengthening for what NOSSA calls the “cosmetic” goal of gaining inches. “You will get more out of life if you strive to accept yourself as you are,” reads the group’s Web site, “short height and all.”

Ross’s parents don’t agree. They see limb lengthening as a way for modern technology to make Ross’s body function a little better. Without it, he would have topped out at four feet or so, and he wouldn’t be able to do simple things like drive without special equipment. With it, he now stands around four–ten, so he’ll be able to drive, use an ATM by himself, and do much more.

However you look at it, limb lengthening is a tough road. The procedure was developed in the Soviet Union after World War II and brought to the U.S. in the eighties. Its target=s are the femur, tibia, and fibula in the leg, and the humerus in the upper arm. During the most serious operation, surgeons drill long, sharp–tipped rods into the leg bones, then crack them with a mallet and sharp chisel. The rods protrude outside the flesh, serving as mounts for a spreader device that can be adjusted to slowly pull the bone halves in opposite directions. As the junction starts to heal, an at–home caregiver—Tracey, in Ross’s case—carefully turns screws four times a day to separate the ends by a total of a millimeter. Length builds up as new bone cells form to bridge the tiny gaps.

This goes on for months, and, yes, it hurts. During two procedures on Ross’s legs—which happened when he was seven and 13—he went through nine months of painful recovery each time, growing a total of nine and a half inches. The total cost will be several hundred thousand dollars—most of it covered by insurance—and Ross will have spent more than two years of his childhood recuperating.

Some of the world’s best surgeons in both specialties—limb and spine—are based in Baltimore, and there’s a divide among them about whether limb lengthening is a good idea. Tracey and Ross were there a few days before our fishing trip for a pre–op consultation with Ross’s spine doctor, a Johns Hopkins orthopedist who’s against using it for height gain. According to Tracey, he scared the hell out of Ross, stressing the small but real chance that the spinal surgery could leave him paralyzed or dead. She thinks he rubbed that in because he was angry about the limb lengthening.

Whatever happened must have been traumatic, because Tracey and Ross are both pretty tough, and I admire the way they band together stoutly in the face of an often cruel world. Several years ago in Baltimore, with Ross in a wheelchair after his first round of leg surgery, they were approached at a train station by a woman who said she was the parent of a dwarf child herself. She knew what Ross’s leg hardware meant and she didn’t like it. She tore into Tracey, telling her that no mother who really loved her child would put him through such an ordeal.

Tracey returned serve and the woman left. She asked Ross what he thought about what he’d just heard. He replied, “How many times have I told you not to talk to strangers?”

I GOT TO KNOW ROSS, his parents, and his older sister, Blair, ten years ago while working in New York, when Tracey and my wife, Susan, became friends at a job. After we resettled in Santa Fe, in 2001, the clan came out for a couple of summer visits, and in 2002 I came up with the bright idea of taking Ross on a camping trip. My goal with this and an earlier fishing excursion was vague but sincere. The transition from brathood to manhood is hard enough for anybody, but for somebody like Ross it’s especially difficult. I wanted to contribute to his overall stock of positive experiences while he grew up.

Whether it’s worked or not remains to be seen. Ross is a smart, fun person, but he prefers urban entertainments like movies, restaurants, the New York Yankees, and the Dominican guys at a neighborhood bodega who show him porn magazines. There’s also the tiny problem of me being incompetent as a trip leader, something Ross has commented on. The first time I took him out—to an overfished Pecos Valley trout pond, where we didn’t catch anything—he told me in his low New York accent, “This sucks. New Mexico sucks. And you suck.”

But that could mean almost anything, couldn’t it? I figure I won’t know until Ross is 30 whether he’ll remember our adventures with misty fondness or will still want to punch me in the groin.

For our camping trip, I took him and his dad, Michael, to a spot northwest of Taos where the Rio Grande and the Red River come together amid dramatic geology. Ross liked some parts of our overnighter—peeing on trees seemed to delight him—but he recoiled against anything that felt wholesome. In a campsite near us were a cute little boy and his dad, a friendly guy from California who was big on earnest declarations about the deeper meanings of outdoor experiences. They came over after sundown, because I’d told the kid I was making s’mores.

I knew Ross would hate them—to this day, I only have to mention this pair and he’ll scream “Nooo!”—but my policy there is simple. If he’s determined to have a bad time, it’s important that I be entertained, even if that requires setups and hoaxes. On the Florida trip, after he refused to come along to tour a wildlife refuge, I briefly conned him into believing that he’d missed seeing an alligator eat a female manatee and all of her young.

But Florida was supposed to be about a good thing—catching fish—which is why I felt so guilty when our last day, a Saturday, dawned with palm–tree–bending winds that never let up. We met Rogan at a different pier, on Captiva Island, and he said it was unsafe to stray too far from shore. So we skulked around, bobber–fishing the docks of zillion–dollar luxury homes.

Ross was fiercely attentive to his fishing rod, even though nothing was happening. At one point I saw his tip go down, yelped toalert him, and watched him as he did everything in textbook fashion—staying focused, reeling steadily, rod tip up. As the fish came to the surface and Rogan got the net ready, Ross departed slightly from the text, yelling, “Get that goddamn motherfucker!”

Sadly, it was a junk fish. Ross kept at it, and soon he reeled in a mangrove snapper that was no bigger than a poker chip. Rogan joked that it was the smallest fish he’d ever seen landed on a hook.

A record. Sweet!

THE NEXT TIME I SAW Ross, in Baltimore in the spring of 2007, he seemed more like his old self, profane but friendly. He was in town for another operation—a limb–lengthening procedure on his upper arms. The dreaded spine overhaul had been postponed. Tracey wanted to shop for a new doctor.

I was sitting in a hotel lobby when Ross came in ahead of his parents, swallowed up by a Matt Leinart NFL jersey. He walked over and said, “Hey,” and I could tell from his tone that he was in a better mood. The arm surgery would be cake compared with the legs. Michael had bought season tickets for the Yankees, so Ross would have a great spring and summer.

Monday was all about waiting rooms and pre–op consultations at Sinai Hospital, command central for East Coast limb lengthening. We met two women from Maryland who were there with a 13–year–old girl who was scheduled for her first surgery—legs—the next day. They were nervous and seemed eager to hear good things about Ross’s case history. Tracey asked him to “stand up and take a bow,” which he did. He seemed justifiably proud of his hard–won inches.

“That’s a miracle,” one of the women said.

Ross stayed cool that day and the next, when we had to show up predawn in advance of his surgery. I’d made arrangements to watch—I’d dragged Ross into my world; I wanted to see his. Inside the OR, my friend was barely visible beneath a pup tent of blue, bloodstained surgical drapes. I could see his right upper arm dangling out, already spiked with five bolts. There was a surgeon on each side, and I watched on an X–ray monitor as one of them struck the hammer blow on Ross’s right humerus.

I left feeling woozy. I also left with a new feeling about Ross. He’d walked into all that without whimpering, so he didn’t need the outdoors, me, or anything else to help him become a man. He was already there.