George W. Bush’s Secretary of the Interior keeps a low profile, keeps her mouth shut, and never picks a fight. Don’t mistake her for a stiff, though. As the steward of 507 million public acres, she has deftly combined an aggressive, pro-extraction agenda and the Bush administration’s wartime clout to steamroll environmentalists. With the big battle over Arctic oil drilling still to come, her fierce partisanship draws comparisons to her onetime mentor, James Watt, but there’s a crucial difference: Norton knows how to win.

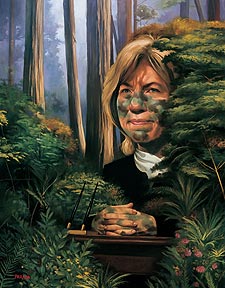

Illustration by Roberto Parada

Illustration by Roberto Parada

GALE NORTON’S PRIVATE OFFICE sits on the sixth floor of the U.S. Department of the Interior, a sprawling limestone pile a few blocks southwest of the White House. The space is almost cartoonishly ostentatious, with its soaring ceilings, paneled oak walls, and enough square feet to swallow up the Oval Office with room to spare.

In Washington, the usual way to handle overwhelming surroundings is to make them part of your act: Welcome to my power vortex—feel free to be intimidated. But Norton’s style, as I learned during a recent interview, is to be underwhelming, unpretentious, very polite, and so careful about her phrasing that she can sound like she’s reciting from cue cards.

It’s hard to blame her for being wary. Environmentalists have vilified Norton from the moment she was nominated to be the 48th Secretary of the Interior, in January 2001, labeling her “James Watt in a skirt” and howling that her pro-extraction and anti-regulation convictions hearkened back to the darkest days of the Reagan administration, when Watt ruled Interior for three stormy years. For a while, her detractors were handcuffed by the don’t-criticize-the-president mood that prevailed in Washington after September 11, but that’s over now.

“The environmental community made a decision after the terrorist attacks to stand down,” says Dave Alberswerth, 53, an Interior official in the Clinton administration who now handles land issues for the Washington, D.C.-based Wilderness Society, one of America’s oldest conservation groups. “Then we found out the other side wasn’t. The war on terrorism became a rationale for their energy goals. The push to open public lands took on new importance.”

In response, Norton’s political adversaries are once again on the march, and the Interior Secretary is heading into a summer of hostile scrutiny on Capitol Hill. Democrats are especially worked up over George W. Bush’s most controversial goal: to drill for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the sacrosanct swath of Alaskan tundra that shelters polar bears and caribou—and that happens to sit atop a sizable pool of precious crude. Smelling brinksmanship, the media have started piling on. Over the last few months, The New York Times has set the tone with depth-charge editorials criticizing Bush’s policies on everything from allowing snowmobiles in Yellowstone to greenlighting oil exploration in Utah’s red-rock wildlands. One was ominously headlined “Landscapes Under Siege.”

In this semitoxic atmosphere, Norton’s aides strain to protect her from any risk of pummeling. Her main media handler is Mark Pfeifle, a hip 29-year-old with the jittery aspect of someone who hears the phone ringing but dreads picking it up. He does everything he can to insert his boss into safe and picturesque Ranger Rick settings—splashing around in the Everglades, posing with the president among towering redwoods. When Norton opens her mouth in public, it usually happens at carefully controlled events where she talks about creatures, natural wonders, and her devotion to compromise with environmentalists. Pfeifle is hyperaware of the potential for PR disaster, and before I meet Norton, he asks, only half-kidding: “Am I going to like this story?”

NORTON GREETS ME at her office door at three o’clock sharp. There’s no entourage, just her, tall and fit at 48, her unruly silver-streaked hair trained into a prim coif. We take our places on two huge stuffed sofas in the center of the room. Pfeifle hovers in the background. Flashing a smile that conveys both curiosity and intense skepticism, Norton says, “So, what would you like to talk about?”

What I’d like to talk about is environmental policy, and the career path that led Norton to take over a powerful federal bureaucracy that oversees 507 million acres of wilderness, national parks, monuments, endangered-species habitats, and other public lands—in all, nearly a fifth of the country’s landmass—with command and control distributed among the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a fistful of other agencies.

Other shrink-the-government politicians attack welfare or rally to pass tax cuts. Why, I ask Norton, has she made stalking environmental regulations her life’s calling? She pauses a moment, as if searching her internal briefing books for the ready-mix response that most closely matches the question. “The outdoors is something I’ve always enjoyed, and protecting that is something I’ve been interested in my whole life,” she says. “Growing up in Denver, I’m sure it started with loving the Colorado mountains.”

Spoken like a true Western outdoorswoman—and Norton can justifiably claim to be one. She’s an accomplished skier, and she’s logged as many hours hiking as her green-certified predecessor, Bruce Babbitt. But as much as Norton loves the country’s wild spaces, she simply cannot abide many of the laws intended to protect them.

“Why has it seemed,” she asks, slowly and carefully,”that the only way to protect the environment is with heavy-handed government regulation?”

The usual answer is that, without those regulations, we might be a nation of mines, oil wells, and clear-cuts, but precious little wildlife and wilderness. Norton’s rejoinder: Not necessarily. “I think today we recognize that economic activity needs to search for ways to protect the environment,” she explains. “And environmentalists have come to recognize that they need to take economics into account.”

When Norton arrived in Washington last year, President Bush gave her a clear mission on the economic front: The government controls a lot of land. There’s oil and coal and natural gas under it. Get it. To that end, Norton has embarked on a radically ambitious mission to fulfill his request, one that ultimately transcends the ANWR debate. With as little fanfare as possible, she is using the internal machinery of the executive branch to quietly open great expanses of public land to oil drilling, mining, and natural-gas exploration.

Leveraging the bureaucracy is a tactic Norton first encountered during her initial stint at Interior in the mideighties, when she worked for three years as a lawyer under James Watt’s successor, Don Hodel. As Norton knows, a huge amount of power resides in the vast stacks of impossibly dreary federal rules and regulations that dictate things like air-pollution standards—and that even spell out where it’s okay to pitch a tent in the Grand Canyon or make a campfire in Yosemite. And since those rules are under the control of the president, he and his agency heads can often change them without rustling a leaf on Capitol Hill.

Norton’s public blandness disguises the fact that she’s been very busy and very effective. Under the watchful eye of the president’s domestic policy staff, which sees to it that cabinet officials adhere to Bush’s agenda, Norton has initiated a slew of changes, easing restrictions on vehicle use and power lines in national monuments, making it easier to dig mines on public land, reversing a hard-won plan to reintroduce grizzly bears to the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area in Idaho and Montana, delaying a ban on snowmobiles in national parks, and targeting millions of federal acres for new energy exploration. All with a few strokes of a pen.

Democrats in the 51-49 Senate are miffed—but, anxiously anticipating this fall’s tiebreaker election, they also sense a political opportunity. The Enron debacle reinforced the widely held view that Bush and his team are in the pocket of the energy industry. The Democrats will emphasize that line this summer, in a series of high-profile hearings—most likely in a Senate committee like Energy and Natural Resources or Environment and Public Works—intended to let voters everywhere know just what Norton is doing. Leading the charge will be Tom Daschle of South Dakota, the Senate Majority Leader.

“On the environment, more than almost any other set of issues, the President has more leeway to make changes without having to go through Congress or consult the public,” Daschle told me. “They are absolutely taking advantage of using executive powers to make serious changes, and no one is paying attention. They are flying below radar.”

Norton is careful not to get into a scrum with a contact player like Daschle. When I mention the opposition’s complaints, she avoids the question with a high-minded pirouette. “In Washington, there’s always an effort to label people,” she says. “I’m not going to turn around and criticize back.” Norton is just as difficult to pin down on the similarities between her views and those of her old boss and mentor, James Watt. It’s a loaded question, and she mulls a good five seconds before venturing an answer.

“There’s a difference between Jim Watt the person and Jim Watt the image,” she finally says. “I don’t think that the reality of his views were as extreme as people now think of them as being. He also was a reflection of the time period. And that was a time period when environmental issues were thoroughly characterized by conflict, each side calling the other side evil and badly motivated.”

What about that cheap, low-down nickname enviros laid on her? “Let’s see,” she says, counting on her fingers. “James. Watt. In. A. Skirt.” She lets out a dry chuckle. “There may well be many ways in which my policies might differ from Jim Watt’s policies,” she says. “I haven’t gone back and looked to see exactly what his views were as Secretary of the Interior. It’s been over 20 years since the last time I worked for him, and I don’t define myself in reference to him.” Norton picks up a Diet Coke and takes a cleansing swig. Subject closed.

A few days later, I call the old warrior himself to see what he thinks. Watt, now 64, is happily retired, and with his wife, Leilani, he splits his time between Wyoming summers and Arizona winters. I catch him one afternoon while he’s soaking up sunshine on his patio in Wickenburg, a town an hour northwest of Phoenix. He’s pretty wary, but we soon come around to an amiable discussion of Norton’s scarlet letters.

“James Watt in a skirt?” he says. “I hope she is James Watt in a skirt! I felt it was a compliment. And I hope she felt it was a compliment. When she was nominated, I had several congressmen call me and say, Jim, is that true? And I said, Well, I hope so!”

Watt calls himself “a big fan of Gale’s.” But then he seems to catch himself, as though he suddenly remembers that, even now, his words of support may do more harm than good. He says he no longer keeps up with politics very closely, and hasn’t really paid attention to what Norton is doing. “I’ve just consciously not got involved,” he says, his enthusiasm fading into a quiet fatigue. “I’ve not talked to Gale for a long time. Years, in fact. I’ve tried to stay out of her way.”

BUMPING UP AND DOWN on the elementary-school bus each morning, young Gale Norton didn’t dream of growing up to become a public enemy to environmentalists. Looking out the window at the 1960s Colorado landscape, she says, all she saw was worsening air pollution. “When you came over the hill in the bus, you were able to see all of the downtown Denver area,” she recalls. “But as I got older, you couldn’t see the buildings anymore.”

Such problems, Norton says, set her on a lifetime path of concern about nature. Her parents are conservatives—her dad, Dale, worked for Learjet and was a Goldwater Republican while her mom, Jackie, was a homemaker. But in tune with the zeitgeist, their daughter developed into a bona fide Earth Day lefty. In high school, Norton joined student groups that organized pollution protests and dabbled in anti-Vietnam protests. “I was a little too young to be a hippie,” Norton recalls of the early 1970s. “But I was becoming more activist, more political. I started out as a Democrat.”

At the University of Denver, where she majored in political science and minored in economics, she organized campaigns for tougher laws against air pollution and shunned automobiles altogether. “My father thought I was crazy,” Norton laughs. “When I started college, they were going to give me one of the old family cars. And I said, No, I was only going to have a bicycle. Cars created air pollution and I didn’t want to have one.”

She graduated magna cum laude in 1975, got a perfect score on her LSATs, and enrolled in the University of Denver’s law program. (She also got married, to college sweetheart Hal Reed.) In law school, Norton evolved toward a more libertarian worldview, as she studied various examples of how federal regulations interfered with market capitalism, with bad results.

By the time she graduated from law school in 1978, Norton, then 25, was reborn as a free-market crusader. (She was also divorced, a split she has attributed to marrying too young.) Norton joined the Lakewood, Colorado-based Mountain States Legal Foundation, a government-thrashing legal clinic funded by the conservative Coors family. Her boss was Watt, then a combative 41-year-old lawyer who found it offensive that politicians in Washington seemed to care so much about protecting the land and so little about the people trying to make a living working it.

Norton and Watt hit the front lines of the Sagebrush Rebellion, the defiant Western uprising against government meddling that took hold in the late 1970s. In dozens of court cases, Norton and her Mountain States colleagues challenged laws that protected the environment at the expense of commerce. “Most of the people I represented were farmers, ranchers, and small businesses who really had a hard time coping with government regulations,” Norton says. But her work wasn’t all about the Little Guy: She also helped represent the State of Louisiana in a fight to kill the federal windfall-profits tax on oil companies. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where she lost.

After three years at Mountain States, Norton shipped off to Stanford for a yearlong stint at the conservative Hoover Institution, where she focused on free-market solutions to problems like air pollution. By then, Watt had been chosen by President Ronald Reagan to take charge of Interior. From her perch in California, Norton watched as Watt’s controversial statements brought about his downfall. Anything that Watt may have achieved in Washington will forever be lost under the weight of his infamous crack that the staff of one government advisory committee he worked with, assembled with diversity in mind, consisted of “a black…a woman, two Jews, and a cripple.”

Watt resigned under pressure in October 1983. A year later, Norton herself moved to Washington to work as a lawyer for the Agriculture Department, at Watt’s recommendation. She soon shifted to Interior, as solicitor in charge of the attorneys at the Fish and Wildlife and National Park Services. In 1987 she ditched the capital and went home to practice law and work for conservative causes. She also remarried, to an investor and avid skier named John Hughes. The two took their vows at the top of the chairlift in Aspen.

In 1991, Norton was elected Attorney General of Colorado. Even as the state’s top cop, she was no grandstander. Local political hands say she kept almost as low a profile there as she does now in Washington. “Gale Norton was not the kind of personality that generated either heat or high visibility,” says Floyd Ciruli, 55, an independent pollster and political consultant in Denver. “I was really surprised when the blowback came from Washington, with people saying she’s going to be the next James Watt.”

Environmentalists battled against Norton’s pro-business ideas, opposing her plan to allow polluters to avoid criminal prosecution if they agreed to clean up their messes. But greens didn’t get much traction. In conservative Colorado, even plenty of Democrats supported Norton’s proposal. During her tenure, her reluctance to prosecute a gold-mining company that polluted Colorado’s Alamosa River with cyanide and heavy metals earned her permanent pariah status among environmentalists. Yet for the most part, she came away with a reputation for being approachable and not overly ideological.

“Gale Norton doesn’t have a lot of hard edges like others who had that job in the past,” says Will Shafroth, 45, executive director of the Boulder-based Colorado Conservation Trust, a landscape preservation group. “She took positive steps by trying to forge partnerships between private landowners and nonprofits.”

If anything, in Colorado she was considered too far to the left. When she ran for the U.S. Senate in 1996, she got clobbered in the primary by fellow Republican Wayne Allard, who used her stance on abortion—she’s pro-choice—as a way to paint her as a hopeless liberal.

IN DECEMBER 2000, Norton was working as a corporate lawyer and lobbyist with the powerful Denver law firm Brownstein, Hyatt & Farber when she got a call from George W. Bush. Would she be interested in coming back to Washington to run Interior? Unknown to her, Colorado Governor Bill Owens—a Republican and a longtime friend—had recommended her to Karl Rove, Bush’s political adviser, who had worked on her failed Senate race four years earlier. “She was the most surprised person in the world when the White House called,” says Owens. “Come to think of it, I don’t think I’ve ever told her that I was one of the people who put her name in.”

Environmentalists, many of them still bitter about Al Gore’s loss in the disputed presidential election, reacted to Norton’s nomination with outrage and a worm-eaten bag of political tricks that, from the start, helped ruin any chance that there could ever be a new mood of compromise between the two sides. Rodger Shlickeisen, president of D.C.-based Defenders of Wildlife, remains unapologetic about the collective blood lust. Norton may have been considered a moderate in Colorado, but to national green groups, her ties to Watt and her pro-industry, anti-regulation philosophy confirmed their worst fears about the Bush environmental agenda.

“We really fought her nomination,” says Shlickeisen. “Literally, in all the years I’ve been doing this, we have never fought someone’s nomination as hard as we did hers.”

In the weeks before her confirmation hearing in January, the League of Conservation Voters took out full-page ads in Washington newspapers, lopping off half of Norton’s face on the margin. “So far on the fringe,” the copy said, “she’s off the page.” Greenpeace dispatched three of its guerrillas to scale Interior’s outside wall and unfurl a red, white, and blue banner that read: “Our Land, Not Oil Land!”

When Norton appeared before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, though, she was downright charming, and slathered on just enough green sweetener to satisfy skeptical Democrats—solemnly vowing to make “conservation of America’s natural resources my top priority.” In the end she sailed through the Senate, 75-24. Ever courteous, Norton didn’t seem interested in rubbing it in. After the hearings, a Greenpeace activist asked her to sign a picture of the banner-bedecked Interior building. She laughed, and pulled out her pen.

Norton may get points for style, but that doesn’t mean greens are wrong about her ideology. In speeches, she enthusiastically details a handful of eco-friendly initiatives, like her proposal to increase funding for the National Wildlife Refuge System, the federal program that sets aside parcels of land as animal and plant habitats. But critics grouse that she uses these easy-to-love programs to deflect attention from her more controversial goals.

“What do you expect?” says Rob Perks, 32, who tracks Interior for the Natural Resources Defense Council, a D.C.-based environmental group. “The White House isn’t just going to come out and announce, ‘America’s wilderness is open for business.’ They say all the right things in public, and meanwhile, with sleight of hand, they’re gutting the laws they don’t like.”

In the months since September 11, Norton hasn’t left much doubt that energy production is her main order of business. In January, the Interior Department dispatched an internal memo to Utah land managers, ordering them to put oil and gas exploration above all else. “When an application for permission to drill comes in the door,” the memo instructed, “this work is their No. 1 priority.” The directive puts land managers under orders to expedite all energy applications, crunching the time they can be studied beforehand.

When I ask Norton why, given Interior’s broad responsibilities, oil drilling should come first, she offers an earnest non-answer: “To a large extent, the question is how I’m personally spending my time, and I’m spending my time on a lot of conservation issues and initiatives.”

Norton, of course, did not mint the concept of allowing extraction, development, and other “multiple use” activities on public land. But she is making it a lot easier for industry to get permission from the Bureau of Land Management, the Interior agency responsible for protecting some 264 million federal acres and whose holdings include most of California’s vast desert and Utah’s red-rock canyons. In the past, for example, if you wanted to dig a mine in such places, you first had to undergo long, tough scrutiny from BLM officials. That meant waiting, sometimes years, while bureaucrats prepared an Environmental Impact Statement to make sure your mine wasn’t going to cause what the government calls “irreparable harm” to the environment.

Not anymore. Last October, Norton did away with the mine-reclamation rule, calling it “unduly burdensome” on mining companies. Now miners simply have to promise to clean up after themselves, and follow an existing requirement to put up money beforehand to guarantee it.

Norton has added another twist to the old rules: Public land managers are now required to get permission before they do anything that might interfere with drilling or mining. In a December 2001 memo, BLM employees were ordered to submit a “Statement of Adverse Energy Impact” if their “decisions or actions” could “have a direct or indirect adverse impact on energy development, production, supply and/or distribution.”

Talk to Interior staffers in Western states, where energy applications are starting to stack up, and they’ll tell you their bosses aren’t being subtle about the push for oil. “You have to get with the program and look more toward extraction,” says a BLM resource specialist in California who recently quit in disgust. “We were told, you will speed up all applications. Basically, anything that comes forward, no matter what kind of impact it will have, will be implemented. And if it’s not, there’s going to be hell to pay.”

The upshot: An extraction land rush. According to Dan Heilig, 46, executive director for the Wyoming Outdoor Council, a conservation group, 81,000 new natural gas wells and 3,200 oil wells are slated to go into Wyoming’s Powder River Basin over the next ten years. At least 3,000 new gas wells are proposed in Colorado, and 100,000 more are slated in New Mexico. These numbers will likely swell in the months ahead, as oil and gas companies flood BLM offices across the West with hundreds of new drilling applications.

INTERIOR SECRETARIES are often visionary types who hope to be remembered as great lovers of the natural world. Bruce Babbitt wanted his image as a true man of the West broadcast clearly, and he populated the ranks of his department with environmentalists and scientists who shared his conservationist creed.

Norton’s public style is lower-key, but during her brief stint, she hasn’t been shy about packing her staff with industry-friendly conservatives who drive environmentalists crazy. Several of her deputies came straight from the industries they now oversee. Norton’s third in command, Associate Deputy Secretary James Cason, 48, was James Watt’s foot soldier in the battle to keep the spotted owl off the endangered-species list, and later became a timber lobbyist. The Department’s top lawyer, 47-year-old William Geary Myers III, was a lobbyist for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. To keep watch over the department’s budget, Norton hired Lynn Scarlett, 52, a tough-minded skeptic of government who used to run the Los Angeles-based Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank.

But no appointment made environmentalists angrier than her choice for number two: J. Steven Griles, 55, who serves as Deputy Secretary. As a Watt deputy at Interior back in the eighties, Griles fought to relax strip-mining regulations. He went on to become a powerful Washington lobbyist representing the mining, oil, and electric industries.

“There is nothing in his background that suggests he has any interest in the land he oversees, except to find quick profits from it,” says Senator Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat who fought Griles’s nomination. “I repeatedly asked him to give me an example of how he’d like to bring people together, to take a fresh approach to protecting the environment. He couldn’t do it. He clearly wasn’t interested.” (Griles did not respond to interview requests for this article.)

Wyden and his fellow Democrats are incensed that Norton is deliberately bypassing them by tinkering with regulations instead of laws. “They can’t do it in Congress, because there is no public support for their agenda,” grouses Representative Henry Waxman of California, one of the most persistent critics of the administration’s environmental policies. “So they’re taking a different approach. They’re trying to do it by hook and crook.”

Of course, greens didn’t gripe so much when President Bill Clinton did pretty much the same thing. In his sleepless last days as commander in chief, Clinton cranked out executive orders creating 20 new national monuments, setting aside five million acres. To make this happen, his industrious staff lawyers dusted off the American Antiquities Act, a 1906 statute that allows presidents to create monuments without asking for a congressional OK. Theodore Roosevelt used this law to preserve the Grand Canyon, plucking it from the hands of developers.

More than a few Republicans saw Clinton’s last-minute creations as a parting screw-you to Bush. Now that Norton’s in charge, she’s doing just what Clinton did, only in reverse. In the process, she’s actually concentrating power in the hands of Washington, rather than fostering the “local control” conservatives like to preach about.

“If Norton’s position is ‘Why do we need a heavy hand in Washington?’ then why do we need her heavy hand coming in and telling locals you will do this and won’t do this?” says Daniel Patterson, 31, a desert ecologist with the Center for Biological Diversity, a Tucson-based group that monitors Interior. “She is doing exactly what she says she doesn’t like.”

One example is all those national monuments Clinton left behind. Fighting to dismantle them would have been politically perilous; instead, Norton has altered them to be more industry-friendly. Clinton left her an opening to do this: In his final-days haste, he didn’t lay out permanent management plans for each of the monuments, so Bruce Babbitt cobbled together interim plans. In March 2001, Norton sent letters to the governors of Utah and Arizona, two states with new monuments, and essentially asked, What don’t you like about the existing regulations? She solicited suggestions about possible “vehicle use…grazing and water rights, as well as the wide spectrum of other traditional multiple uses that might be appropriately applied to these lands.”

One response came whistling back from Jane Dee Hull, Arizona’s Republican governor, who detailed the various changes she wanted. There are, for example, hundreds of head of cattle legally grazing in Arizona’s new Sonoran Desert National Monument, and every now and then, a few of them get picked off by a hungry mountain lion. Under Clinton’s interim plan, says Daniel Patterson, “it was okay to hunt down and kill the offending mountain lion. But only that one. They couldn’t go around indiscriminately killing mountain lions.” They can now. In her letter, Hull asked Norton to “delete” the language about “specifically targeting individual predators rather than animal populations.” Norton did just that.

Norton similarly rewrote the rules to allow for easier creation of “rights of way” in the monuments (government-speak for power lines and pipelines), and to let dirt bikes and dune buggies do their thing in roadless areas. She also cut a paragraph that required land managers to report concerns about environmental damage from extraction industries.

Norton and Hull say their actions are simply the exercise of states’ rights. A spokeswoman for Hull says the governor asked Norton to make changes because the interim rules interfered with long-planned Arizona development projects. “Had Interior talked to the state before the monuments were created,” she says, “these issues could have been dealt with. As it was, we had to do it after the fact.”

Johanna Wald, who tracks Interior for the NRDC, says she’s never seen so many drilling and energy proposals flowing out of Washington. The bosses back at Interior used to give people in the field wide latitude to make decisions affecting the land they oversee. “Now,” Wald says, “they’re being sent a clear signal, a red flag, that says, don’t do what you think is right, because we are going to look at it and you are going to have to stand up and explain it.”

NORTON WILL HAVE a much harder time outmaneuvering the opposition over the most bitterly disputed issue of all: drilling for oil in a 1.5-million-acre portion of the 19-million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Allowing oil exploration in ANWR is a big deal in part because, unlike other federal lands, ANWR isn’t a multiple-use space. Created by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1960, it’s supposed to be off-limits to just about everything that would interfere with the birds and caribou and polar bears that live there—no snowmobiling, no hunting, no oil exploration. Greens are fiercely protective of that hands-off status, fearing that if Norton and Bush succeed in pushing their way onto ANWR, it’s only a matter of time before other protected wilderness areas—and maybe national parks—get drilled.

By now, the arguments are familiar enough: Environmentalists claim drilling in ANWR would damage pristine tundra and caribou and polar bear habitats, all for a six-month supply of oil that won’t be available for at least ten years. In the other corner, Norton and the Republicans say the refuge sits atop a vast sea of crude that can be softly, safely sucked out of the ground without leaving a trace.

Both sides exaggerate to make their case. The “six month” supply of oil that environmentalists talk about is a loose statistic based on the U.S. Geological Survey’s 1998 estimate that there are roughly 3.2 billion barrels of recoverable oil under the refuge. But there could be much more. No one can know without drilling.

Meanwhile, Norton and her allies insist that new methods make it possible to tap oil without making a mess. “Certainly, the technology has improved,” Norton says. “I don’t think we were focused on the use of ice roads when we looked at development in the 1980s, or the ability to do horizontal drilling from far away. The environmental impacts are far less today.”

But such assurances only tell half the story. Once oil is found, wells and pipelines will proliferate across ANWR’s surface. And no matter how good the technology, oil wells leak. Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay oil fields average 400 spills a year.

Even Norton’s own staff has gotten in her way on ANWR, sometimes refusing to serve up the sort of data she’d like. When Norton tried to argue her case for ANWR exploration to a Senate committee last year, she offered statistics that showed the 120,000-strong Porcupine Caribou Herd wouldn’t be significantly affected by the drilling. Her own Fish and Wildlife biologists strongly disagreed, however, and produced solid evidence that herd animals often calve in the very spot where the oil rigs would go.

Norton didn’t include that evidence. Instead, she based her testimony on a competing study sponsored in part by the oil industry. Even then she botched a critical fact, saying that the herd usually calves mainly outside the drilling area. In reality, Fish and Wildlife studies showed that the calving took place inside the proposed site 27 out of the last 30 years. Greens accused Norton of deliberately lying to Congress. Her beleaguered press aide Mark Pfeifle called it an unintentional error.

This exasperating back-and-forth seems destined to go on forever. Last summer, the Republican House appeared to break the stalemate when it successfully tucked an ANWR drilling provision into the president’s energy plan. No one was more delighted than Norton, whose backstage maneuvering may have done the trick. She endured marathon days chatting up Republican members of Congress, letting them know just how much the president would appreciate their support—and how terribly disappointed he’d be if he didn’t get it. Gulp. “She almost lived up here for a while,” Utah Representative Jim Hansen, who wrote the bill, told The Denver Post at the time.

Unfortunately for Norton, the Democrats aren’t bewitched. Daschle has bluntly told Bush and Norton that no matter what the House does, no Arctic drilling plan will get past him. These days, Norton’s closest ally in the Senate may be Frank Murkowski, 68, the ornery, oil-fed Alaska Republican. Early last year, Murkowski took Norton on a guided tour of the oil fields in Prudhoe Bay, where they delivered fresh navel oranges to locals. The two became fast friends.

“I’ll say this,” Murkowski laughs. “She is a hardy Westerner. We went up to Barrow and Fairbanks. It was 78 below with windchill. She didn’t complain once. I kept telling her she’d make a fine Alaskan.”

“AREN’T YOU GOING to ask me about hiking and skiing?” Norton asks near the end of our interview. “I’m an avid skier,” she says, easing back into her sofa. “I can go down anything, I just look bad.” She smiles at her joke. For the first time in an hour, she actually seems relaxed.

Norton says she has but one regret since moving to Washington: Less trail time. “My schedulers keep getting driven crazy by the fact that they can’t fit hikes in my schedule.” A few weeks before, on a trip to Yellowstone, Norton says she was thrilled to see the word “Hike” written on her calendar. “And we hiked, like, a hundred yards!” she exclaims. “That’s not a hike!”

This is the face Norton wants you to see, the easygoing trail walker who, much to her surprise, woke up one day in charge of a whole lot of nature. So far, her success has depended on juggling public support of environmental protections with her far quieter maneuverings to undercut them. She may soon find that she’s been too successful in fulfilling her energy goals, making her a fat target for the president’s political enemies. With the help of greens and Democrats in Congress, even people who can’t spell BLM will be inundated with television ads and direct-mail packets that put the words “oil well” and “national monument” in ominous proximity.

But environmentalists have plenty of their own problems. Norton’s success has shown that their combat methods are getting tired—on the national level, they really only work when there’s a Democratic majority in the Senate or House to back them up, or a sympathetic judge. For Democrats, making the environment the centerpiece of the fall congressional campaign has its potential drawbacks—the chief one being that most people don’t vote the environment, even though they tell pollsters that green issues are important. Not that Democrats have much choice. The war on terrorism has made Bush so popular that, at least for now, he’s vulnerable to attack on only a few issues—and the environment is one.

They’d better hope it works. If the strategy fails and Republicans win the Senate—which could happen—the greens’ time-honored tactics won’t do much good. Gale Norton will be heading back to Alaska, and this time, she’ll be bringing more than a crate of oranges.