The old Nethercott place sits on the Jackson Hole valley’s version of skid row, just off Wyoming 22 and Village Road in the rustic outpost of Wilson. From the back deck, you could throw a wet November snowball into Dick Cheney’s yard. Across the lane, thousand-dollar pickups and ten-thousand-dollar snowmobiles sit outside million-dollar double-wides. Until 2005, this 6,000-square-foot, 11-bedroom rambler was a church camp, the three-quarter-acre lot filled with so many Winnebagos and laundry lines that you couldn’t swing a tetherball. Now it takes a sledgehammer to find evidence that the Sunday-schoolers were here at all. Inside, there’s cussing and yelling and spitting and blowing dust boogers out of nostrils farmer style as a pack of ratty skiers tears the house apart.

Freeskiers

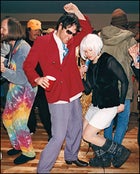

Charlotte Moats and Jeff Annetts get down at the SKI House.

Charlotte Moats and Jeff Annetts get down at the SKI House.Freeskiers

Teton Gravity Research founder Todd Jones

Teton Gravity Research founder Todd JonesFreeskiers

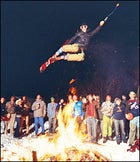

Housemate Mark Longfield, towed behind a snowmobile, launches over the fire.

Housemate Mark Longfield, towed behind a snowmobile, launches over the fire.Freeskiers

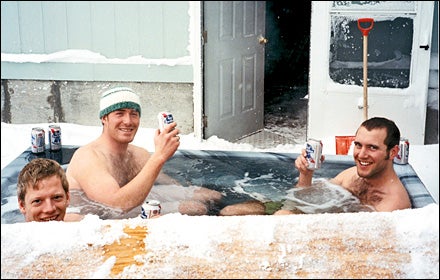

The neighbors warm up.

The neighbors warm up.“Other buyers were scared away from the place,” says its owner, freeskier, Dartmouth graduate, and junior real estate mogul Charlotte Moats. “That’s how I got it so cheap.” By “cheap” she means about $600,000ÔÇö”basically the price of a vacant lot.” Of course, the neighborhood still has a ways to goÔÇöis that a couch the folks are burning next door?ÔÇöbut Charlotte fully expects the property’s value to triple by the time she gets ready to sell in the spring of 2008. If she can bring herself to sell, that is. “The place has good bones.”

Charlotte pries open a trapdoor in the laundry room, part of the original 1916 house, to reveal seven layers of old linoleum. Lowering myself clumsily down after her like a skier falling into a tree well, I find her spidering around behind the shiny new plumbing. When she bought the place, it had six old-school septic tanks; the house’s potable water tasted vile enough that they suspected it came from the same “aquifer.” This blows Charlotte’s mind. “Eighty church campers took showers here,” she says. “I was like, My God, do you know what that does to the septic tanks?”

If she can get the house back on its feet, it represents a respectable, if financially hairball, business model for staying in Jackson Hole. Charlotte is only 27. But seven years after making a name as the youngest skier to win the 24 Hours of Aspen endurance race, she’s practically retirement age in a sport that values the freshest kids doing the sickest tricks. Even with 11 first descents in Alaska’s Chugach Range and appearances in a host of ski films, Charlotte still makes less than the guy installing the plumbing. So what’s a dean’s-list Ivy League geography major to do in a sport where you might spend an entire winter setting up a six-minute film segment that your sponsors had to pay to get you into? Ask Charlotte and she’ll tell you: a really big flip.

Screw the “brothel law,” a valley ordinance designed to prevent too many skids from shacking up in too few square feet. Until Charlotte can renovate the camp back into sellable single-family splendor, she’s paying the mortgage with roommatesÔÇö11 of them (not counting the floor surfers), mostly overeducated, undersponsored ski bums shelling out between $300 and $600 a month. After a particularly epic bender, the housemates tagged this place the SKI HouseÔÇöSigma Kappa Iota. But you can’t pretend you’re in college forever, and that’s why Charlotte is trying to turn what feels like a season of The Real World: Jackson Hole into Flip This Old House.

Deep in the crawlspace, we’ve made it over to what Charlotte pulled me down here to see. “Check this out!” she says. The center of the house is held up by 16-inch-diameter stumpsÔÇötwo of them, cut from local lodgepole pine, the bark still on. The SKI House is a tree house! Charlotte is grinning: “This won’t pass code.”

EXTREME SKIERS WHO COME TO JACKSON HOLE inevitably face one of three choices: (1) Move back east, go to work for the Man, and ski twice a year. (2) Continue to suffer a dozen roommates or live in your van down by the Snake River. (3) Evolve fiscally by selling the Man an expensive-ass “Hummer House,” and repeat as needed.

Some choose door number one. Justus Meyer, a big-mountain skier who lived in the house after graduating in 2005 from Harvard, where his father managed the university’s endowment, is now working in private equity in London. Housemate Mark Longfield, 29, left Jackson in 2006 to practice business law in Delaware; four months later he was back, working remotely for his firm. Meanwhile, plenty keep eking out a living through door number two, patching together sponsorships and service jobs. But in the last several years, number three has become the ticket for an increasing number of winter athletes hoping to make it in one of the richest counties in America, where, as of July, the median home sale price was $1.175 million, 28 percent higher than in 2006.

Snowboarding mountaineer Stephen Koch got his Wyoming real estate license earlier this year. Olympic biathlete Erich Wilbrecht went from guiding fly-fishers on the Snake to hawking real estate in 1993. Next to the weather, it’s what everyone in Jackson talks about. “Any ski bum who worked hard, begged, borrowed, or stole to buy real estate in ski towns before this past wave was lucky and/or smart,” says Rob DesLauriers, 42, a ski mountaineer and Jackson real estate agent who allowed his friends first crack at condos in his slopeside Hotel Terra, a 32-unit green development opening this winter. “I loved living in my van and on friends’ floors, but it gets tiresome,” says DesLauriers, who in 2006, along with his wife, Kit, and photographer Jimmy Chin, made the first American (and, for Kit, first female) ski descent of Everest. “Then at some point we seem to change a bit, and that’s natural. We want a house, the van died, etc., and then, yes, it’s hard. Usually the ski celebrity doesn’t choose to get older and pass├ę. It’s going to happenÔÇöso what are the options? Going from star to anything is tough.”

“Real estate is a great avenue for athletes,” says Rick Armstrong, 37, one of the first professional freeskiers in Jackson. “I love to see someone use their mind so they can live here.” An Alaska heli-skiing pioneer and fixture of myriad ski flicks, including the upcoming December release Steep, “Sick Rick”sold his Toyota four-banger pickup and a garage full of ski gear in 1994 to make the down payment on a $110,000, 1,200-square-foot condo with his wife-to-be, Holly Menton. “It was the least expensive condo in Jackson,” Armstrong says. “Two years later, after a full-on remodel, we sold it for $230,000. Now the price of entry here is crazy expensive. A bottom-of-the-barrel, 600-square-foot condo starts at 340 grand. And that’s in marginal repair.”

“I actually looked at Charlotte’s house when it was for sale,” Armstrong says. “It needed a lot of love. A lot of sweat equity.”

Charlotte has drawn heavily from her line of sweat equity. A small-towner from Fairlee, Vermont, she’s no trustafarian investing with Monopoly money. “My dad was a hippie,” she says. “My parents didn’t believe in debtÔÇöat all. Not even a simple mortgage. Cash for everything.” Her father, software designer Alan Moats, raised the family’s vegetables, raced on the World Cup telemark circuit, and entered Charlotte in her first race when she was seven. (She won a cookie.) At 12, she enrolled at the Burke Mountain Academy, a ski prep school in northeastern Vermont, and at 14 she was the 1995 Junior Olympic slalom gold medalist. She switched to freeskiing in 1999, ditching a racing career at Dartmouth to spend winter terms off, traveling and competing. Her athleticism, along with her looks, got the attention of sponsors like Spyder, V├Âlkl, and, currently, Columbia Sportswear. Her reputation for nailing big, poetic lines got her segments in the Warren Miller films Storm, Impact, and Off the Grid, as well as Teton Gravity Research’s High Life.

Charlotte’s foray into real estate began in 2003 with a condo replete with bad shag and puke stains on the wallÔÇöthe former band pad for the Mangy Moose Saloon. She scraped to save eight grand, a 5 percent down payment on the $160,000 price. Then she traded up, selling the condo for another, less urpy place in town and ditching that for the SKI House. “As the house increases in value,” Charlotte says, “I borrow back against the new appraised value by either refinancing the entire mortgage or taking out a home equity line.” Until last summer, she was also working part-time for Countrywide Home Loans, processing mortgages on her kitchen table.

But a window may be closing on the flipping scene, as this year’s mortgage crisis attests. Locals are discovering that, like a favorite run tracked out by 9 a.m. on a powder morning, an easy loan is a thing of the past. “Now you have to have 20 percent down and a strong credit rating,” says Armstrong.

Add to that the fact that there are only so many bargains in a town like this. “All of the really horrible places are getting gobbled up,” Charlotte says, the corners of her mouth turning down. It’s clear that this is a shame, that one day soon the vomit stains may be gone.

UNTIL THEN, THERE’S WORK TO DO. On a sunny day in November, the mason is on his way over to size up the rock fireplace. Librado “Balo” MartinezÔÇöthe 33-year-old Oaxacan contracting genius who, like log-house chinker Arnie Fong, came with the house and lives upstairsÔÇöis inside hanging Sheetrock, and Charlotte is haggling over a commode. Looking Jackson glam in flared designer jeans and a puffy vest with a faux fur collar, she paces in the muddy snow, sparring on her cell phone with a supplier who delivered a toilet in the same dog-shit-brown color of the paneling they just ripped out, instead of the champagne taupe she’d clearly ordered. (“Fighting with these guys is never fun,” she says, hand over the phone, “but if I can save a thousand dollars per call …”)

If that weren’t enough, she’s trying to break her one-year-old Lab mix, Onyx, from growling at the paper boyÔÇö”Sorry!” she calls after the kidÔÇöand it’s time to go chop wood. One of the first fronts of the season is rolling in, and there may be only a few days left to lay in firewood before snow buries the forest roads.

Charlotte heads inside and plops onto the couch. “Oh, my GodÔÇöis this mouse shit?”

Sprawled on the great room’s thirdhand furniture are several of her housemates, pulling on wool socks for the firewood run. Charlotte’s boyfriend, Jeff Annetts, picks a pellet from the cushion. A 29-year-old big-mountain skier, sportswear model, waiter, and “manny,” Jeff is one of those ski bums whose haircut appears to cost more than his car. Like many of their friends, he’s talented enough to be sponsored (by Fischer skis and, starting this winter, Columbia) but not big enough to make a living skiing. He’s bunking in a room off the kitchen while he works on his own renovation, a house near the base of Snow King, Jackson’s in-town ski area.

The talk this morning has been real estate. Charlotte has become something of a business role model for the boys, having dropped in first andÔÇöso farÔÇöstuck the landing. Now housemate Travis Owen, 25, a University of Vermont grad hoping to become a filmmaker, has convinced his mom to lend him the money for a down payment. He’s already been to one open house today, a disappointment that he paints with phrases like “orange,” “shag carpeting,” and “guy sleeping on the couch.” “I felt like I was walking into a drug deal,” he says.

Jeff goes through the specimen, gives it a sniff. “I think it’s just seeds.” Apparently a pack rat has moved in under the sofa.

“They’re sharp on the end,” Charlotte says.

Travis takes a look. He’s the house clown, infamous back in Vermont for losing his job as Rally Cat, the UVM mascot, after the local Burlington news affiliate caught the huggable catamount getting crocked in a downtown bar. Now he lays out some SKI House common sense: “What would you expect from something that came out an asshole that small? Yours was that little, you could put an edge on a turd, too.”

This time of year, before the lifts open and the snowpack settles, things are fairly quiet at the SKI House, less MTV than HGTV. Residents work as many restaurant hours as possible, hang out at the Village Caf├ę bar at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, and sleep. Where are the 24-hour party people? Other than a cereal bowl in the sink and some boots by the door, life seems tame, if a little grungy. It looks like nothing’s been dusted since the church campers left. “The guys try,” Charlotte says, “but even when they think they’re being clean, they’re slobs.”

Today the wood run qualifies as what they call “getting stuff done.” We head out in two pickup trucks, making for a burn clearing two miles up Mosquito Creek Road. Charlotte and I thread her white Dodge Dakota with the glitchy transmission up the muddy, rutted road, past a shack that appears to have been built from baby-blue particleboard. “I love that place,” she says, jouncing on the seat with excitement. “I so wish I could buy itÔÇöit’s so run down!”

Travis and Jeff are up ahead in Matt Annetts’s Toyota. Matt, Jeff’s younger brother by two years, is a pro snowboarder (“He could be the next Jeremy Jones,” Charlotte says) who lives in the basement with his girlfriend, bartender Marissa Krecker, 25. Like his brother, he’s sponsored by a medicinal-tasting energy drink called Go Fast, which he breaks out while Jeff tries to fire up the chainsaw he borrowed from Balo.

“Good, huh?” Matt grins, awaiting my approval. “Yeah? Nice. The Austrian honey.”

I ask Travis who his sponsors are. “I just have one,” he says. “Jeff Annetts.”

There is laughter and hooting over the blue smoke and cough of the saw. The boys fell a large dead lodgepole pine that snaps and shakes the ground as it hits. There’s a touchdown-style victory dance, and a case of Pabst Blue Ribbon replaces the Go Fast. As the boys celebrate, Charlotte is quietly getting stuff done. She shoulders a log that probably weighs 30 pounds less thanshe does and hikes it to the truck. She does this all afternoon.

“You evaluate your risks before you move into action,” Charlotte told me once, and it’s something she repeats as a business mantra on the snow and off. “And then just focus on getting it done.”

TWO MONTHS LATER, ON A THURSDAY in early January, the snowpack is still thin, but the SKI House is coming along. Taped on the beer fridge is a Sunday-school tract uncovered behind the paneling: WHY GOD MADE LITTLE BOYS. Some trim work still needs to happenÔÇöalwaysÔÇöbut the drywall has been taped and painted, the light sconces are wired, and if the varnish on thenew wood floor dries in time for the band to set up, there is going to be one helluva housewarming party here Saturday night.

The house has filled up since I was here last. Spencer Morton, 29, another Vermont expat and a forward for the Jackson Hole Moose Senior A hockey club, has moved into the basement. Alden Wood, 29, an L.A. TV producer turned ski-film producer, has parked her Beemer in the gravel lot out front and moved in across from Charlotte’s room. Ski patroller Chessa Jones, 29, is living in the room next to Jeff’s. Mark Longfield has returned from his exile back east. And Patrick is back! On-again, off-again resident Patrick Heaney, 29, is taking an extended holiday from his Ph.D. work in material science at the University of Wisconsin, bringing with him a pimped-out┬áSki-Doo snowmobile and a party vibe. Already the patent holder for a ski-mounted bottle opener, he’s convinced the bartenders at the Village Caf├ę to mix up a cocktail he calls the Trendy BitchÔÇöOrange Crush and Crown Royal, served over ice in a pint glass with a little black straw. Everyone who’s anyone has been tottering around the Caf├ę in ski boots holding a bright-orange Bitch.

Charlotte is on edge. There’s an issue that’s been weighing on her, and this morning she has a meeting at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort. She had a good year exposurewise, including a nationwide tour with Off the Grid and TV spots like VH1’s Lift Ticket to Ride and Dan Egan’s Wild World of Winter. She figured that making the resort’s team of sponsored athletesÔÇöessentially getting her lift pass compedÔÇöwould be automatic, but it’s turning out to be about as simple as ordering commodes.

The publicists have told Charlotte that they won’t be sponsoring her this yearÔÇöthey’re going “in a different direction.” This puzzles her. She’s a great media face for this adult amusement park, and all she wants is to be able to ski. In addition to mountain ambassador Tommy Moe, the resort has signed up six local skiers, including Teton Gravity Research regular Micah Black, 37, and two women: fellow Warren Miller star Lynsey Dyer, 25, and Jess McMillan, 29, winner of the 2007 Freeskiing World Tour.

“We try and focus on young athletes who are up and coming,” resort spokeswoman Anna Olson explains to me later by phone.

Charlotte is the first to admit that she’s not the most aggressive skier in town. “There are girls here who can stomp me on the mountain,” she says. “There will always be someone better than youÔÇöthis is Jackson. You can’t talk in a bar, because your plumber can set world records.” Like Whistler, Jackson has become a proving ground; every day a new skier moves here, trying to make it for the cameras of the TGR guys.

“It’s funny because I am still younger than most of the ‘up-and-comers,’ ” Charlotte says. “But I can’t be an ‘up-and-comer’ anymore because I started when I was so young. So it’s true, I have to constantly keep proving myself.”

Charlotte is still invested in her career. “I figure I’ve got another decade or so,” she says. “Assuming of course that you succeed in constantly reinventing yourself along the way.” This winter she plans to ski in an all-women’s movie from Rage Films, as well as another for Warren Miller. There are more competitions, including the Jackson Hole Freeskiing Open. Of course, she also wants to get involved in an affordable-housing development. She wants to go green, throw grand parties, and have a bigger garden. Still, no pro should have to buy her own lift ticket.

“Maybe I’ll move to Whistler for the season,” she says.

“What, and leave Jackson?” Jeff says.

While Charlotte heads off to try to straighten things out, the boys are going skiing. There’s not much snowÔÇömaybe 50 inches, a drought for the Tetons in JanuaryÔÇöand wind has created some sketchy layers in the snowpack. Caution is king.

Jeff, Matt, Patrick, and I suit up and hit the mountain. Even on a powder day, Jackson’s elite skiers spend nearly all of their time out of bounds. Jeff and Matt drop big, confident lines; they know this mountain blindfolded and squeeze every bit of thrill out of the terrain. Genuflecting on his telemark skis in a hunter-orange jacket, Patrick shoots into the trees and squirts back onto the line. This is hard, graceful play, every day, with melon grins under goggles and brotherly punches in the arm.

Around noon, we exit the resort through the lower Rock Springs gate and stop below Fat Bastard, an infamous 50-foot cliff band, to start the 20-minute bootpack up to Rock Springs Bowl. A few other locals are gearing up too, all of us intently watching three skiers on the snowfield above Fat Bastard. A popular traverse runs beneath the cliff, and a slide could bury skiers commuting between the Green River and Rock Springs bowls. Jeff set one off near here in 2001, in fact, when he first moved to the Hole. Luckily no one was hurt.

“They’re not gonna drop that with this snowpack, are they?” Jeff says now.

“Dude, that’s just stupid,” someone says.

One snowboarder, Mott Gatehouse, a friend of the guys, points his video camera up at the three figures, in case one decides to drop. Then, just when it looks like the would-be huckers think better of the situation and start to retreat, there is a thunderous crack, and the run-in fractures and breaks loose. We watch horrified as the first skier points his skis downhillÔÇöhis only optionÔÇöand goes over the cliff. The avalanche sucks the other two with it as it cascades onto the traverse below.

There’s a collective “Oh, fuck.” We’re a football field away, and we click into our skis and sidestep toward the slide while Jeff draws his cell phone and calls Valley Dispatch. But before we reach the debris field, we get waved off. Another group, including a doctor, is already digging. Two of the skiers have uncovered themselves.

When Matt, Patrick, and I get back to the resort, we find Jeff, who waited for the ski patrol, standing outside the Village Caf├ę talking with sheriff’s deputies. “The guy died,” he says. His name was Justin Kuntz, we’ll learn the next morning. Charlotte doesn’t remember it at first, but she skied with the 25-year-old at Whaleback Mountain, New Hampshire, when they were little kids.

The SKI House crew is sobered and saddened, yet no one is surprised. They’ve all skied stuff just as stupidÔÇöhasn’t everybody here? It’s sometimes easy to forget that life is not a Warren Miller movieÔÇöthat Neverland is all play, but the consequences can be fatal.

SATURDAY NIGHT, THE FLOOR is almost dry, and the half-dozen kegs of PBR have been delivered. Charlotte is fretting over last-minute party details. “What if the whole town comes?” she says. Is the floor spec’d to hold 300 drunken dancers? “I’ll ask Balo,” she says. “He’ll know.”

She’s found a high school kid to drive a shuttle van from the Wilson public lot; the band Mandatory Air, featuring the redneck-wild Miller Sisters on vocals and Mark Longfield on keyboards, is setting up; and the boys have built a sweet kicker jump next to a pile of scrap wood destined for the bonfire. The idea is for Patrick to tow skiers behind his snowmobile off the jump and over the blazing fire.

There is a costume theme: Come as anything but yourself. Charlotte is wearing a vampy skirt and a platinum-blond wig. The UPS man is here, sporting an Afro. Patrick is in a gorilla costume, bucking kegs like Donkey Kong. About an hour in, he fires up the Ski-Doo and starts looping people around the house and over the fire. The landing is a bit flat, but the buzzing skiers don’t seem to mind. Then a collective howl goes up. Skiing behind the sled is Jeff, buck naked, slinging toward the crowd at 25 miles an hour. He hits the kicker at speed and spread-eagles over the fire, eggs to the flame, lands clean, and speeds off into the dark, his moon to the throng.

Inside, a kid who just arrived in town tries to talk Charlotte into renting him the windowless closet off the great room. “Let me think about it,” she says. Mandatory Air kicks into “Movin’ On Up,” from The Jeffersons, a fitting theme for the housewarming. The place smells of funky polypropylene, and the dancers are getting shellacked.

The new floor holds. The next morning, it’s stained and sticky with beer. Todd Jones, one of the TGR founders, is still asleep on the couch, rolled up in his down parka like a mountain gnome. The house itself seems a little hungover.

The SKI House’s days are numbered. Before the snow flies again, Balo will put in a new kitchen and a proper concrete foundation, and Charlotte will haul out those lodgepole stumps. Hopefully, by next spring, the place will be closer to resembling a single-family residence, with six bedrooms and a bathroom for each one. It may finally even make code.

It’s nearing noon, and the place isn’t going to clean itself. Charlotte begins to pick up beer cups, yawning as Onyx wanders through the debris field. “When the the kitchen is finished,” she says, “I think I’m gonna have a quiet dinner party.