Halfway Round

Teenager Abby Sunderland was on track to become the youngest person to solo-circumnavigate the globe. the ocean had other plans.

I WAS 16 AND ALONE in the southern In┬şdian Ocean, exactly halfway into my attempt to become the youngest person to sail solo around the world. My brother Zac had set the record the previous year, when he was 17. And if he could do it, I definitely could, too.

When you're that far south, you expect bad weather. But my 40-foot racing yacht, Wild Eyes, was holding up against the swells, and I would stay below, tied into bed, reading books, listening to music. One of the best parts of the day was checking my e-mail.

About three weeks out of Cape Town, the storm hit. There were mountains of water all day. The boat was knocked down four times, but, with its heavy ballast, it always righted itself. Night falls really early down south. At 4 P.M. it was already dark, but by 5:30 the storm had died down, so I called home. I'd had some trouble with my engine, and my dad helped me get it running again. Then the call dropped. I set my sat phone down on the chart desk. While I was replacing the engine cover, a rogue wave struck.

I flew across the cabin and hit my head. Everything faded out for a second. When I came to, I was sitting on the ceiling in a foot and a half of water. Things were falling everywhere. It was pitch black. After 20 seconds, the boat slowly rolled back over.

The mast was gone. I could feel it missing as the boat righted. When you lose your mast, you immediately think, OK, I'm going to jury-rig that. I sliced through some lines that were blocking the door and went out to see if the hull was damaged. The carbon-fiber mast was dangling in the water; the boom, also carbon fiber, was snapped in half. There was nothing left for me to jury-rig. I sat outside on deck in my jeans and T-shirt for a few minutes thinking there was nothing else I could do. Waves were dumping over the boat. I was shaking from fear and cold.

Back inside, both of my Iridium phones were soaked and shorted out. I knew that activating my emergency beacon was going to trigger an all-out rescue effort back home. I was sitting there soaking, still kind of dizzy and nauseated from my fall, thinking about what would happen if I pushed that button. Finally, I did. It was like admitting defeat. Then I set off my little handheld EPIRB as well, so they'd know it wasn't an accident.

My most immediate concern was the dangling mast, which could have punched a hole in the side of the boat. But I knew that if I tried to cut it loose while dizzy, I'd end up in the water. I left it for the night.

I couldn't sleep. I was having nightmares. By morning the boom had started to wear a hole in the ballast tank. I found my saw and crawled out on deck. There wasn't a lot to hold on to, and the boat was rolling gunwale to gunwale. I tied myself to a broken stantion and started sawing. Every time I spied a big swell coming, I untied myself and got inside.

I sawed, and I prayed. Ten seconds after I started praying, a huge plane flew overhead. I ran down below and turned on the radio. The voice was really broken up. They were calling, “Wild Eyes … Wild Eyes.” I said, “This is Wild Eyes.” They told me a rescue ship was 24 hours away.

I finished cutting the mast loose. When the boom slid into the water, it smacked the VHF antenna. Twenty-four hours later, I turned the radio on, waiting for the ship to call. Three hours later: nothing. I was starting to worry, when another plane flew over. I could hear them calling, but they couldn't hear me. I started shooting off flares.

The rescue ship appeared out of nowhere. I had been outside maybe a minute before. I thought, Oh, my gosh, where did that come from? It was a 150-foot French fishing ship. They came alongside and lowered a dinghy to the water. I hopped into it and they brought me over. There was this long ladder I was supposed to climb, but just as I was about to step onto it, a big swell lifted the dinghy up to the rail of the boat, and the guys pulled me aboard.

One day I will sail around the world, solo, nonstop and unassisted. I don't need to do it straightaway. For now, I'll do high school and get a driver's licenseÔÇöall that normal stuff. I have to work hard to keep myself busy. I'm daydreaming when I'm supposed to be writing papers for school. I get bored, and my mind wanders off to the boat.

This article has been changed since publication. Originally it said that the mast and boom in Abby's boat were wooden. They were in fact both made of carbon fiber.

Fire in the Sky

WORST CASE: STRUCK

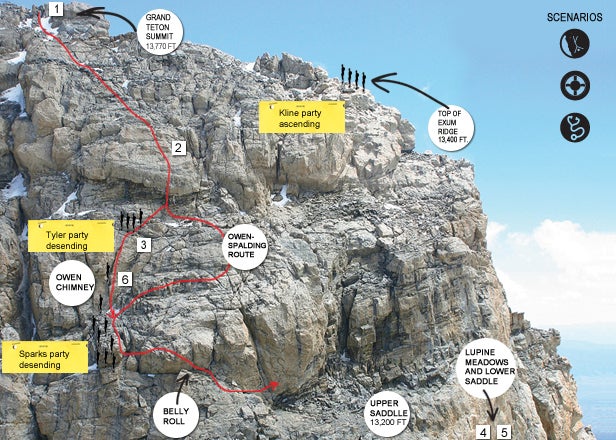

On July 21, just after noon, 17 climbers were caught in a lightning storm as they descended from Wyoming’s 13,770-foot Grand Teton. The ensuing epic required a record 83 rescuers. This is how one group of five unguided climbers, the Tyler party, was saved.

1. Summit, 9:15 A.M. The last of seven Exum Mountain Guides and their 15 clients top out. “There were big black clouds and lightning on the horizon,” says Exum co-owner Nat Patridge. By 10:30, all guided groups have descended.

2. 200 to 600 feet from the summit, 12:15 P.M. A series of strikes pummels the three unguided groups still on the mountain: the Tyler party, spread along the Owen Chimney; the Kline party, on the Exum Ridge route; and the Sparks party, at the Belly Roll, on the Owen-Spaulding route. Brandon Oldenkamp, a 21-year-old in the Sparks party, falls 2,500 feet to his death.

3. Owen Chimney,12:18 Steven Tyler, the leader of his group, resuscitates his son-in-law, Troy Smith, who hasn’t been breathing for 30 seconds. Meanwhile, Tyler’s younger son, Dan, is dangling unconscious in his harness 50 feet below. When he comes to, his legs don’t work, but he manages to rappel to the bottom of the chimney. Steven calls 911.

4. Lupine Meadows, 12:27 A page goes out to Grand Teton National Park rangers at Jenny Lake. They gear up for the rescue.

5. Lower Saddle, 11,650 feet, 2:02 The first rangers arrive at the Lower Saddle by helicopter. Ranger Jack McConnell and Exum guide Dan Corn begin their 100-minute ascent. “There were people all over that mountain,” says pilot Matthew Heart, who would fly rescue runs and recon flights for the next eight hours.

6. Bottom of the Owen Chimney, 3:40 McConnell and Corn reach Dan Tyler. He still has no use of his legs, his fellow climber Henry Appleton has no use of his right leg, and Troy Smith has regained consciousness. All are flown off the mountain in “screamer suits,” body harnesses that dangle by a rope beneath the chopper.

5:06 Another storm moves in. More lightning, snow. “The first bolt hit with this tremendous scream and roar,” says ranger Marty Vidak. Only Jack McConnell is zapped, when he touches a charged rock.

7:15 Steven Tyler is short-hauled to the Lower Saddle and flown to Lupine Meadow, where he joins his son Dan in an ambulance. “It’s not a terrible experience to ride on the end of a rope,” says Steven.

7:56 All 17 climbers are off the mountain. Seven are short-hauled out, while the rest are escorted to the Lower Saddle and flown to Lupine Meadow. Every climber bears the classic entry and exit wounds of a direct lightning strike. Five are admitted to St. John’s Medical Center in Jackson, and one is taken to Eastern Idaho Regional Medical Center. Climber Betsy Smith loses a finger in surgery.

Cutlass Supreme

When you go out looking for the Nigerian Taliban, bad things happen.

╠ř

A HOT FRIDAY MORNING in August 2007 in the Nigerian trading town of Maiduguri. From the cramped backseat of a compact car, I squinted through the windshield, looking for a group of thugs who called themselves the Taliban. I’d come to Maiduguri, once a respected center of Islamic learning, to investigate the rise of a group of militants who terrorized locals for “protection” money and took their name from Afghanistan to try to shore up their power. I’d been here for three weeks with Irish photographer Seamus Murphy, but so far we’d struck out. All I saw through the windshield was hundreds of men teeming about, waiting for noon prayer to begin. I looked but couldn’t find a single woman.

Our translator, Mohamed, a soft-spoken English teacher, had brought us to the market to change U.S. dollars into Nigerian naira. It wasn’t a great idea to have two pink-skinned people in the market on a holy Friday, so we stayed in the car while Mohamed searched for the money changer. Seamus sat in the passenger seat, idly snapping photos. Having worked in Afghanistan for more than a decade, he was accustomed to throngs like the one surrounding our car, and so was I. Still, I felt claustrophobic as the midday sun rose.

I glanced out the window as Seamus took photosÔÇöclick, click. What was he looking at? I saw nothing special.

Then, in the crowd, I noticed one man staring at our car. He strode up to the open passenger window. I glanced at our driver. He was half asleep, hunched over the wheel.

“Give me that film!” screamed the stranger, clad in his Friday whites. Seamus tried to explain that there was no film, but the man had never heard of digital cameras. He poked his head through the window. A crowd gathered behind him. Suddenly, six hands, then eight, reached into the car to snatch the camera; we held on against the tug of hands, gripping tightly as Seamus tried to reason with the men, murmuring quietly, as one might address a spooked animal.

That’s what the mob felt likeÔÇöa beast turning more agitated with each second. People began to rock the car, and then, in an instant, every man was suddenly armed with the long machetes Nigerians call cutlasses. Through the window I saw a sea of knives.

We are dead, I thought. The mob rocked the car but couldn’t open the doors, because there were no exterior handlesÔÇöa design flaw Seamus had been bitching about ten minutes earlier.

The crowd’s rage moved like water. The bloodlust periodically petered out, then rose again in a wave, cresting over the car roof. Each breath felt like it took an hour. Mohamed appeared in the crowd. Men grabbed him.

“Please use your fists, not the blades,” he pleaded before he disappeared beneath a hail of blows.

Our driver pushed his door open, climbed out, and ran away. But, perhaps in a twisted gesture of mercy, he left the keys in the ignition. Seamus grabbed them. The car swayed like a dinghy in a squall. Then, out of the crowd, a man in mirrored sunglasses appeared with a tiny, wizened elder.

“I’m a policeman!” Sunglasses screamed. The crowd continued to rock the car. Suddenly, another face appeared at the window.

“Move away from the car!” commanded a tall man in white. I could tell by his dress, by his small, white hat, that he had been on his way to the mosque.

Together, this religious teacher, the policeman, and the tiny old manÔÇöa community leaderÔÇöpushed themselves against the windows, absorbing blows. It took all three to wrest our translator from his attackers. Then Seamus opened the door and all four men climbed into the car. The religious teacher took the wheel and nosed the car through the slowly dissolving mob.

We felt a bump in one of the front wheels as we drove off. When we reached a safe distance, we stopped to see what the problem was. One of our attackers had shoved a cutlass into the tire. The policeman told us we’d just met Nigeria’s Taliban.

Back in the Saddle

A brutal crash ended Jens Voigt's 2009 Tour de France. he wasn't looking for a repeat the next year.

AS YOU CAN IMAGINE, no cyclist likes to abandon the Tour de France. It leaves a terrible taste in your mouth. So, in 2009, when I was still lying in the hospital after my crash with a fractured cheekbone and concussion, I’m like, OK, this is not going to be the end of my Tour de France story. I want to finish with proper honor. Well, I think it was on the 16th stage again this year when my front tire blew up. When you’re doing 60 or 70 kilometers per hour, there’s not much you can do except think, Ooh, this is going to be bad. And then boomp, you’re down. So I’m lying there on the road, everything hurts, but nothing is broken. I have 20 patches of road rash. My arm is bleeding. Blood is running down my elbow to my fingertips and dripping to the ground. It’s like some bad horror movie. My bike’s front rim is broken. The derailleur has fallen off. The frame is shattered. Then I see everybody coming past. Five riders. Twenty. Thirty riders. Way back I see one guy all alone and I think, Fuck, he’s the last rider, and now I am. I’m just here bleeding. Then I start thinking, No, I’m not going to let this happen again. I’m going to make it. There’s nothing going to come between Paris and me. But at that moment there was no team car behind me, because they followed Andy Schleck, our captain. So I start saying to the doctor and a policemen nearby, “Hey, guys, I need a bike. Someone get me a bike!” Pretty soon a car pulls up with a spare from the juniors program. It was canary-bird yellow and the size of a little baby mountain goat. It had toe caps. As I’m getting on, the broom wagon stops next to me and the driver looks out like a damn vulture, saying, “Hey, you, want a ride?” I’m like, “No, I’ve got to go. I’ve got to make it.” After 15 or 20 kilometers, I get my normal spare, which my team director left with a policeman, and eventually I catch the last peloton group. A teammate looks at me and says, “Jens, what the hell happened to you?” I’m bleeding still. My jersey’s back is ripped off. But I’m so happy to be in the last group. I just could have kissed every single rider. I was like, Oh, my God, I love you all. It was such a relief knowing we’d make the stage finish. I’m going to be safe and make it to Paris!

Crash-Test Dummy

Brad Zeerip knows how risky it is to ski the backcountry alone. which is why he brought an air bag.

Avalanche

Zeerip in the slide's aftermath, “looking up at what I got flushed down”

Zeerip in the slide's aftermath, “looking up at what I got flushed down”ON MAY 3, 2010, I started skinning up Oscar Peak, near my home in Terrace, B.C. It’s a place that is rarely skied. I ski in the backcountry more than 120 days every year, 30 to 50 of those days by myself. It was spring. The conditions seemed perfect, since new snow had come on wet and heavy and then firmed up with some cold weather.

I dropped in and made three or four cuts. It felt stable, so I started skiing down. Ten turns in, I could see surface snow sloughing around me. I moved to my right, along a rock face, to get away from the slough. Then the snow started melting all around me like wax.

I tried to ski down and to the left, but I didn’t have the speed. The slide hit me at full force, pulling my skis out from under me. I pulled the cord on my Snowpulse, an avalanche pack with an integrated rescue air bag that I’ve skied with every day for the past two winters.

The bag inflated around my head like a giant pillow. It was a reassuring feeling. Then the slide took hold of me. I lost my view of the sky as snow boiled up over me. The slide built into a deafening, pulsing roar. I felt my left ski hit something and grab. I thought I was going to be split like a wishbone. But then my ski ripped apart and I pulled my feet together.

The torque of my ski catching flipped me around. I was still on my back, but now riding the slide at full speed upside down, when I hit something and started cartwheeling. I’m still convinced that if the air bag hadn’t been inflated around my head, it would have split my skull like a pumpkin. I was still hauling ass, but the bag had pulled me up to the surface. I must have slid a good 1,500 feet down a steep 45-degree-plus chute.

The slide started to slow down and set up. I knew this was the most dangerous partÔÇöwhen you can get buried. Another tongue of the slide came again all of suddenÔÇölike waves hitting a beach. It hit me hard, and I started swimming and kicking with the other ski to try to stay above it. I went back under, but the air bag pulled me back up. Then a third wave hit.

When it finally settled, I was buried on my side with my head and left shoulder above the snow. My right leg was buried and attached to a broken ski. My left leg and right ankle were definitely injured, but nothing seemed to be broken. I got my shovel out of my pack and dug myself out within a few minutes.

Getting back to my car was more difficult. I spent over six hours crawling, sliding on my one broken ski, using my poles as crutches, and stumbling out of what should have been a one-hour hike. I had a SPOT Personal Tracker and could have hit it for help, but I felt a strong sense of personal responsibility.

I’m embarrassed. I’m not proud that I was caught in a slide. But the air bag saved my life. I certainly will never ski without it.

In July, I went back and found my hat. Another big, wet slide had swept it down to the valley floor, and it had melted out in the snow.

SCENARIO NATURAL DISASTER STRIKES WHILE ABROAD

YOUR WAY OUT: Smart preparation, like packing a SPOT satellite messenger device () or signing up with Global Rescue (), will save you in most situations, especially in wilderness areas. Didn’t bother? Take down the phone number for the nearest American embassy (); they’ll get local authorities on your side or direct military personnel to pluck you from the rubble. Otherwise, head to the usual expat hangouts, like a famous hotelÔÇöeven if they’re in shambles. Intact or not, those areas often see the first response from American authorities.

Huevos Fritos

Sometimes a man is his own worst enemy.

╠ř

Jeans

“I felt like I had just ridden a rhino bare-assed for 30 miles.”

“I felt like I had just ridden a rhino bare-assed for 30 miles.”THIS IS A SMALL STORY, inhumanly cruel, and it ends with a terrible howl. It takes place in a dark forest on the Kamchatka Peninsula, in the Russian Far East, an inhospitable place known for exploding volcanoes, mosquitoes that swarm like hornets, and, most fearsome, bears. The story itself contains a cosmonaut, more grizzlies than almost anywhere on earth, a criminally amused wife, and the unimaginable horror that befell its narrator, a pitiable soul named Poor Me.

So. Let’s get it over with.

I’d come to Kamchatka to connect with the Russian mafia, who had, in their ever-inspiring entrepreneurial spirit, begun stealing entire rivers, netting wild salmon, and shipping illegal caviar back to Moscow. My wife had come along; she was obsessed with catching one of Kamchatka’s legendary monster trout, something in the 20-plus-pound range. Which she would do, a bona fide Grade Two worst-case scenario: too much bragging.

We had an idle day before our expedition launched into the distant wild, so we piled into our fixer’s pickup and drove an hour north of Petropavlosk, the capital, to a national park at the base of a Mount FujiÔÇôlike volcano. The road ended at a cluster of dachas next to a frothing river. The park headquarters, clearly marked on our map, did not exist, and the park itself, on the far side of the river, was what it had always beenÔÇöa vast, dense spruce-and-birch forest, accessed by a shabby cable-and-plank footbridge.

“Let’s cross over and go for a hike,” I suggested, and my wife said sure and our fixer, Rinat, said absolutely not. “We will absolutely be eaten by bears,” Rinat declared, and settled into the truck to await the eventual recovery of our chewed-upon corpses.

Because this story also contains a six-ounce can of pepper spray stuffed into the left front pocket of my jeans, I felt it was not irrational to be respectfully nonchalant about the bears.

My wife and I clambered across the rickety bridge and followed a primitive road leading deep into the sun-dappled forest. We hiked ahead, alone in the woods, enjoying the solitude, until suddenly a rusty blue Soviet-era van pulled alongside us. The driver, a lean, blond-haired man, wagged his head at us, frowning, and said something in Russian. His wife and teenage son nodded gravely.

“We don’t speak Russian,” I said, and the man switched to En┬şglish. “Go back,” he said. “Are you crazy? The bears will absolutely eat you. You cannot walk here without big gun, eh?”

“It’s OK,” I said. “I have pepper spray.”

“You have pepper spray?” he snorted. “What for? To make bear cry before he absolutely eat you? Turn back now.”

Ten minutes later we came upon them again, parked in a glade, each carrying a carbine and a bucket. Again, a lecture from the driver. Then he sighed and said, OK, as long as you are here, come with us. They were headed up to a meadow to pick berries.

“From this place,” the driver said, “you have excellent nice good view of volcano.” I asked him where he’d learned English, and he revealed that he was a cosmonaut on vacation with his family.

We followed them through the woods to a raging river spanned by a fallen tree, its wet trunk just wide enough to walk across, slowly, carefully, single file. My wife looked at the whitewater rapids below the log and said she wasn’t doing it. The cosmonaut said, “Come on, just up the top of bank you can see volcano.” I told my wife I’d be right back. But the opposite bank led to a treeless plateau overgrown with brush so high it was impossible to see anything at all. Just ten more minutes, said the cosmonaut, but I knew I couldn’t abandon my defenseless wife, so I headed back down the steep bank.

As soon as I took a couple of steps out onto the log, I lost my balance and instinctively crouched to steady myself. I have a permanent visual image of what happened nextÔÇömy wife waiting on the bank, her quizzical expression turning to wide-eyed, jaw-dropping astonishment as she watched me, poised above the river, rear up from my crouch in a roar, digging frantically into my pocket, pulling out an object that resembled a smoke grenade, and hurling it into the rapids.

Bending over to regain my balance, I had triggered the can of pepper spray, its aerosol blast locked into an open position aimed directly at my crotch. Imagine a tiny jet engine in your boxer shorts. Imagine that engine throttled up to its white-hot afterburn. How to minister to such a grievous, potentially life-altering injury, how to relieve the suffering? Only the kindest, most selfless nurse would have a clue.

When I finally stopped howling, my wife had trouble keeping a straight face, eyeing my wincing, bowlegged gait back through the forest. Perhaps something about watching a guy self-immolate his nuts brings out the mirth in women. I felt like I had just ridden a rhino bare-assed for 30 miles. My wife kept reminding me that the afterscent of pepper spray, once its stinging properties have faded, is a bear attractant, smelling much like an order from Taco Bell.

That would be one overcooked burrito with a side of huevos fritos.

Thumb Sucker

In hitchhiking, there's a fine line between being open-minded and foolish.

Hitchhiking

There was no key in the ignition, just a rat's nest of wires. This was someone else's lowrider.

There was no key in the ignition, just a rat's nest of wires. This was someone else's lowrider.THERE ARE probably dozens of ways a hitchhiker could wind up riding in a stolen car, but I only know the stupid one. I’d been standing on the highway leading out of Abiqui├║, a small town in northern New Mexico, for maybe 20 minutes. It was barely enough time to put Sharpie to cardboardÔÇöSANTA FE, ALBUQUERQUE, TEXASÔÇöand certainly not enough to forget the first law of recreational thumbing: Don’t be a dumbass. That rule should hold until you’ve waited for hours, when heat and boredom and the fear of being stranded start affecting judgment. I’m afraid that wasn’t the case.

It was a morning in July 1996, and traffic was heavy. Most of the vehicles were small vans or sedans that slowed so kids inside could wave. Then a lowrider rolled into view, floating over the asphalt until the engine suddenly gunned and it swerved to hit me. I jumped into some weeds as it slid to a stop, then backed up, spraying gravel. The occupants were kids in bandannas and wife beaters, the driver in his twenties, the passenger at most 15, both laughing. When the younger guy rolled his window down, the elder said, “Get in.”

This idea struck me as imprudent. “Where are y’all headed?”

“Albuquerque.”

“Dang, fellas, I’m not going to Albuquerque,” I said.

The driver pointed at the cardboard still held to my chest. “Your sign says ‘Albuquerque.'”

I looked at their car, a long, two-door Monte Carlo from the seventies, painted glass-glitter royal blue like a drum kit, with a perfectly matched crushed-velvet interior. The next town, 20 miles away, was Espa├▒ola, the renowned Lowrider Capital of the World. This was an invite to the kind of cultural exchange that prompted me to hitch in the first place. I got in.

The ride got weird immediately. As I wedged myself behind the passengerÔÇöthe front seat was tilted back so far the car was effectively a two-seaterÔÇöhe adjusted his mirror so it pointed straight at me. The driver did the same with the rearview. Once we were moving, they kept their eyes on me and talked in Spanish, which I didn’t understand. Then the driver addressed me. “You fucked up, man. We’re going to Kansas. And you’re going with us.” I opted not to believe him, perhaps as some self-preservation reflex. Or maybe it was because when he gave me a menacing look and turned up the stereo full-blast, “Vacation,” by the Go-Go’s, came on. He hit the eject button, then cussed and beat the dashboard. The cassette was stuck in the tape deck.

Which was when I realized that the tape wasn’t his, and neither was the car. There was no key in the ignition, just a rat’s nest of wires hanging from the steering column. This was someone else’s lowrider.

For the next 15 miles I reminded myself that the other reason to hitchhike was to get home with a story to tell. This would qualify. The guys went quiet as the tape played on, apparently a mix of eighties hits. “(There’s) Always Something There to Remind Me” played as we passed roadside stands selling statuettes of Catholic saints.

When we hit Espa├▒ola I started to worry. The driver took a left and headed north, clearly not the way to Albuquerque. I decided that if we actually were going to Kansas, there’d be plenty of gas stops on the way and chances to bolt. But he turned into a neighborhood and stopped. I looked out the window at a row of adobes and started thinking about The Silence of the Lambs. I pictured two scenarios. In one I broke free as they led me to a house; in the other I got eaten.

We sat without talking for a long five minutes, the driver’s eyes never leaving the mirror. But he seemed to be looking past me. Finally he said, “A cop has been following us the past ten miles. I think he’s gone.” He turned the car around and rolled into town.

He stopped again, at a little rim shop. “I need to talk to a man who sold me some wheels,” he said. “They don’t fit. You can wait in the car or you can move on.”

I tried to look like I was mulling it over. That seemed gracious. “You know, you guys have been great. But I think I’ll try the highway.”

So There You Were…

We put out the call for your own worst-case scenarios—scary, dangerous, or just plain dumb. The winner was the only one that made us blush.

On a spring-break trip in the Florida Keys, eight of us decided to camp out on a barrier island. It was supposed to be a remote key, roughly two miles out. But after three hours of paddling, we realized the “island” was only a mangrove forest, and we had to paddle back. Daylight was fading fast. An hour into the return trip, cold and exhausted, we called search-and-rescue. But since there wasn’t a medical emergency, we were advised to contact a towing service. We couldn’t afford it, so we kept paddling. Soon a pontoon boat came sidling up. The captain yelled, “Need a lift?” It wasn’t until we were on board that we noticed the boat was labeled Couples Massage Trips. While explaining to the captain how we’d gotten stuck, we began hearing passengers down belowÔÇöpassengers in the throes of passion and not modest in the least. After 15 minutes, an attractive woman came up and told the captain he was needed below. She took the wheel, and he headed down. Within minutes, another “couples massage” had begun. When we reached land, we quietly drove to the nearest pizza place and ate in silence. It was the best pizza I’ve ever eaten. And, yes, it was the most beautiful silence I have ever heard.