Tiny Dude, Giant Wave

Some of the world’s scariest waves explode off the coast of Portugal, and North Shore gunslinger Garrett McNamara won’t stop until he’s tamed an elusive wave he calls Big Mama

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

At five in the morning, there’s water in the streets of Nazaré. Dark and swirled with sand, it comes racing across the wide beach and into the town square, wetting the shoes of late-night revelers and lapping against the monument to the mulhers, the long-suffering women of this ancient Portuguese fishing village. You can’t see the waves yet, but the surf roars like a 747, echoing off the cliffs to the north. Big Mama is here.

An hour or so later, at Nazaré’s gritty fishing harbor, Garrett McNamara starts pulling on his wetsuit. Behind a makeshift screen, in a cinder-block warehouse once used by fishermen, his wife, Nicole, helps him wriggle into a tight-fitting equipped with pads and armor to protect him from the beating he’s almost guaranteed to endure out there. If something goes really wrong, his base layer consists of a CO2-armed inflatable vest, capable of floating his unconscious body to the surface.

As McNamara dresses, he inhales and exhales deeply to oxygenate his blood and focus his mind. A 46-year-old professional surfer from Hawaii who has chased the world’s marquee big waves—�Ѳ������������’s, Teahupoo, Cortes Bank, and Jaws—the stocky, dark-haired McNamara will take on almost anything. He has even attempted to surf tidal waves produced by calving glaciers, an escapade that nearly got him killed. In 2007, a bodyboarder from Nazaré sent him a photo of a huge wave breaking close to a rocky headland. “It looked just like Jaws, my favorite wave, but with nobody on it,” McNamara says. He vowed to get a closer look.

He first showed up in the fall of 2010, at the invitation of town officials who viewed the surf as a potential tourist attraction. He liked what he saw, riding waves in the 50-to-60-foot range, big enough to hold his interest. He came back the next October, and on November 1, 2011, he caught a wave that was said (in a press release issued by the town) to be 90 feet tall, which would have made it the biggest wave ever surfed. In photos and video that flashed around the world, McNamara was seen streaking down an enormous pyramid of water, hammering over the chop like a Masshole bombing Killington. The image was terrifying and exhilarating: tiny dude, giant wave.

“Everyone gets that,” says Bill Sharp, the spike-haired impresario who runs the , which are like the Oscars of monster surfing, with cash prizes up to $50,000. McNamara won that season’s prize for the biggest wave, which Guinness certified as a world record at 78 (not 90) feet. The ride made him a national hero in Portugal and led to a 60 Minutes Sports segment with Anderson Cooper. Then, in January 2013, McNamara rode an even bigger-looking wave that was said—again by others—to measure 100 feet, far taller than any wave ever surfed.

True or not, the claim instantly made McNamara one of the most famous surfers in the world, up there with Kelly Slater and Laird Hamilton. But the reaction from his tribe of fellow big-wave riders was less enthusiastic. Some of the criticism focused on the wave itself, which many dismiss as being a mountain of mush rather than a majestic curl. McNamara often gets slagged, too, in part because he uses jet skis to tow into the things. “There’s hundreds of thousands of people that have the technical ability to be towed into a giant wave at Nazaré,” paddle-surfing legend Shane Dorian scoffed in the surfing publication Stab. “Hundreds. Of. Thousands.”

Why the hate? One reason is that tow-in surfing—which pioneered in Hawaii in the 1990s—has lately gone out of fashion and paddling is back in. But in a rare moment of candor, a blogger for Surfing magazine admitted, after the 2011 world-record wave, “We dismissed it because it’s Garrett McNamara, as much a cowboy as a legitimate big-wave surfer.”

According to his detractors, McNamara is a loudmouth who takes wild risks in search of an adrenaline rush and then can’t stop “claiming” his accomplishments. “People are always attacking him, saying, Garrett’s such a kook, and he gets towed in and loves claiming it and calls the media,” says Brock Little, a veteran big-wave surfer and Hollywood stuntman who grew up with McNamara on the North Shore of Oahu. “It makes me want to defend him.”

McNamara has been doing a pretty good job of defending himself. He , which in the past he had won in numerous categories (Biggest Wave, Overall Performance, and the coveted Best Wipeout, his personal specialty). He said the event was tainted by having an alcoholic-beverage sponsor, Pacifico beer, which puzzled many people, since McNamara had not previously been known as a teetotaler. Some argued that he was afraid his January wave would be dismissed on the grounds that it barely broke and perhaps wasn’t as tall as billed. But in an e-mail to Bill Sharp in 2013, Nicole complained that her husband had been “shunned” by the surf industry.

Now, with this swell shaping up on Super Bowl Sunday 2014, the cowboy was hoping to ride a wave so big, so unquestionable, that it would prove all his doubters wrong.

Two days earlier, on Friday, January 31, I woke up to this e-mail:

“It is going to be huge on Sunday!!! We are going to surf. It is the biggest swell we have ever surfed. No wind…Please do not tell anyone!! All the best!!! Garrett”

I boarded a plane for Lisbon that night.

I’d been weirdly fascinated by the Nazaré wave since I’d first seen it online. Usually, I watch surf movies and videos as a way to relax and open up the creative spaces of my mind. The footage from Nazaré was more menacing than soothing. The waves, dark and foam streaked, looked like they were about to break on top of a huge old fort with a lighthouse on the roof. They tossed the surfers around like toys, but sometimes they showed mercy. In one mesmerizing sequence, the Moroccan rider Jerome Sahyoun falls off his board and gets hoisted to the top of a wave, which tseems ready to fling him over the falls. At the last second, he somehow manages to escape down the back side.

This was my second trip to Portugal: I had come over in late November 2013 and spent a few days with McNamara and Nicole, a slim, intense brunette who’s 17 years younger than him. There was supposed to be a swell then, too, but by the time I showed up the waves had fizzled. On that visit, McNamara had hinted at the existence of an even bigger, previously unknown wave that broke in the same general area. He and his circle—a small group of local officials, surfers, and videographers employed by a Nazaré-funded effort known as the Project—called this one Big Mama and said it could reach a legitimate, verifiable height of 100 feet or more if the conditions were right. Which they seemed to be as I headed to Portugal a second time. Would it fizzle again? Fool me once…

As my flight crossed the Atlantic at 40,000 feet, we passed over a massive storm named , which was preparing to slam into southwest Ireland. Portugal would be its next stop. Surfers in Ireland and northern Spain were flocking to their favorite wave spots, but the unique geography of Nazaré would guarantee the biggest breakers of all.

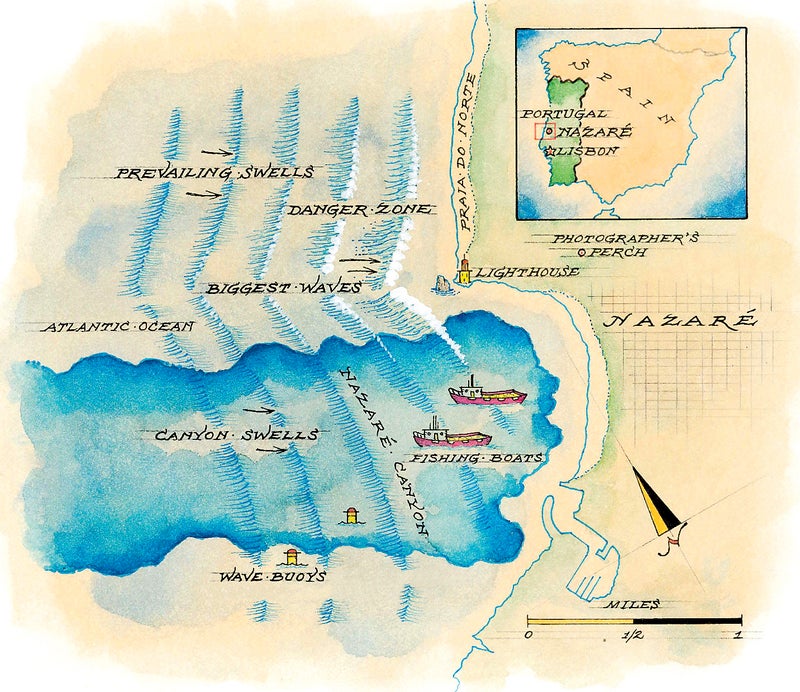

The whitewashed little town, population 15,000, sits at the end of a huge undersea canyon that runs in a northeasterly angle from the open sea. There are of the United States, but they get deep dozens of miles out in the ocean; the Nazaré canyon drop-off is only yards from the beach, and it ultimately reaches a depth of more than 15,000 feet. Historically, the canyon attracted fish by the ton, which is why Nazaré has been a commercial-fishing hub for 500 years. But it also created the monster wave that McNamara compared to , the famous break off the north shore of Maui.

The Nazaré wave is so big, first, because Portugal sticks farther out into the stormy North Atlantic than any other part of Europe except Ireland. And, second, because it is composed of not just one wave but two. The prevailing swells tend to march in from the north or northwest, which is why the town huddles to the south of the point. But the canyon also gathers its own swell from the west-southwest, funneling it directly toward the fort, which has somehow clung to the cliff since 1577. The canyon swells are subtler, until they hit the edge, where the depth changes suddenly from several hundred feet to about 60. When the two swells combine, they rear up into what McNamara calls a “rogue wave” that explodes, hugely and frighteningly, just off the rocks in front of the lighthouse.

These waves haunted the town for centuries, like the mythical monsters and dragons of ancient folklore. Making matters worse, Nazaré had no natural harbor, forcing fishermen to launch their boats directly off the beach, often into pounding surf. (The current there is called the widow’s rip.) The Portuguese government finally opened a modern fishing harbor in 1986, but even then the monstrous waves claimed victims, many of whom were drowned on the wild, exposed beach to the north, Praia do Norte.

“To my parents and grandparents and uncles, who were all fishermen, that beach was a place of death,” says 36-year-old Dino Casimiro, the local bodyboarder who first reached out to McNamara. The older generations were shocked when Casimiro and his friends began riding the waves off Praia do Norte. But by the early 2000s, Nazaré was well known in the bodyboarding community as a fun but challenging shore break, the site of many competitions.

McNamara saw something more: the potential to ride the kind of monster wave that rarely forms close to shore. “Here you have a rogue wave that breaks on the beach,” he says, “which doesn’t happen anywhere else.”

And he was the first guy crazy enough to try and ride it.

McNamara wasn’t born to surf, necessarily—he came into the world in landlocked western Massachusetts, in 1967—but he’s certainly a natural risk taker. When he was 18 months old, he wandered away from the Berkshires prep school where his folks worked. He made it over a mile, in his diaper, before a neighbor found him. “He had an extreme childhood,” says his mother, Malia McNamara, on the phone from Hawaii. “He was always escaping.”

Malia, whose birth name is Mary, was a wanderer herself. In 1969, when Garrett was still a toddler, his parents moved to Berkeley, California, during the era of peak hippie. They cofounded a commune in Sonoma County, where Garrett spent all day running around naked with other kids. One of his earliest, fondest memories from this period is an image of, in his words, “watermelon seeds on my ding-dong.”

The commune lasted two years before his mother and a guy named Mad Bob split town with Garrett in tow (parking a younger son, Liam, with her husband). Along with Mad Bob’s two daughters, they headed south into Mexico in a VW bus, living on Malia’s modest inheritance as they bounced from town to town. Mad Bob ran off to work as a strongman for a traveling circus, and he was replaced by a man named Luis. After multiple trips south, they all ended up living in Belize, in a house on a lagoon.

That idyll lasted a while, but eventually the inheritance ran out, and Garrett wound up in Berkeley with his father. Malia joined a group called the Christ Family, whose members had forsaken their worldly possessions to wander the countryside barefoot, wearing only white robes. On the plus side, their “sacrament” was smoking pot.

At ages six and four, respectively, Garrett and Liam joined their mother for an extended trek around Northern California and the Pacific Northwest that left their feet blistered and their souls mortified. “Imagine walking up your street where all your friends are after being gone for six months,” McNamara recalls, “and you have nothing but a white robe on and a little white blanket rolled up strapped to your back—no shoes, no nothing, exactly what Jesus wore!”

The experience scarred him, and he was only too happy when, a few years later, his mother decided to move them to Hawaii. “I decided I really wanted to stay somewhere and be straight and raise the kids,” she says. “I wanted them to not have to be embarrassed of me and to have a home.”

[quote]McNamara hauls himself over a whitewashed cement wall and I follow, dropping down only to realize that we’re at the bottom of the funicular railway. I’m pretty sure this is illegal.[/quote]

They ended up in a barracks-style apartment complex known as Cement City that McNamara calls “the armpit of the North Shore.” He remembers eating his Frosted Flakes with powdered milk, because they were on food stamps and real milk was too expensive. The saving grace was the generosity of a neighbor who gave the boys their first surfboards. The sport became the McNamaras’ escape. “I think he found solace in the water, away from everything,” says Nicole.

The North Shore turns out pro surfers the way the Dominican Republic produces big-league ballplayers, and despite their relatively late start, Garrett and Liam both found some success in the lineup. Liam proved to be the better competitive surfer, although his reputation, and maybe his scores, were damaged by a tendency to get into scrapes, and sometimes fistfights. Garrett did his best, until a 1990 mishap at Waimea Bay left him with a broken back and effectively ended his career. By age 30, he was pretty much retired, running a . But he wasn’t cut out for a nine-to-five life. “Every day, I would drive by these perfect waves on my way to work,” he says. He hated it.

When McNamara was 34, he made the first of several radical life decisions. At a point when many of his contemporaries were finally phasing out, he decided he would go back into surfing, big-time. “Riding big waves was my passion,” he says. “It’s all I wanted to do.” He wrote his goals down on a sheet of paper. It’s an ambitious list that includes winning the , or the Eddie, a prestigious contest in honor of the legendary North Shore lifeguard, held when conditions are big enough at Waimea Bay. He spent months training at Pipeline and Sunset, the classic North Shore surf spots. And then, in 2002, he got his big break.

In the opening scene of the classic 2004 big-wave documentary , we see a massive, 50-foot Jaws wave curling over, with more intense fury than God’s own washing machine. Suddenly, a lone figure shoots out of the barrel, arms raised in triumph. It’s Garrett McNamara, a guy everyone on the North Shore thought was washed up. “It’s never been equaled, before or since,” Sam George, a former editor of Surfer who cowrote the documentary, says of the ride.

The Jaws barrel capped an amazing comeback year for McNamara. In January 2002, he’d won $70,000 in a tow-in contest at Jaws—the first time he’d ever surfed there. That summer, he , in Tahiti, that made the covers of surf magazines. He had exposure now, and that attracted sponsors like No Fear and Red Bull that would pay him to surf, traveling to wherever the swells were best. “I was always Liam’s brother—like, Who is this Garrett guy?” he says. “But that solidified it. And it was like, OK. I’ll keep surfing.”

McNamara tells this story as we’re driving back to Nazaré from Lisbon. The night before, he did an on-stage interview in front of an enthusiastic Portuguese crowd, answering questions about surfing and life and spirit from a journalist whose main job is covering the Pope. I can’t help but point out that, according to the speedometer, he’s flying down the A8 highway at 130 miles per hour. “Am I going that fast?” he asks. “Wow. Holy shee-it!”

He doesn’t slow down much. Even in the fraternity of big-wave surfers, a group that rocker Dave Grohl has praised as “the craziest motherfuckers I’ve ever seen,” McNamara stands out as a gambler. Never the most stylish of riders, he’s known for taking off late or deep on a wave, where one of two things will generally happen: Either he’ll get “barreled” and enjoy a perfect tube ride, or he’ll get the living crap pounded out of him. One particularly nasty wipeout at Teahupoo, a notoriously shallow reef break, scraped most of the skin off his right leg. In 2007, he and tow partner Kealii Mamala went to Cordova, Alaska, . Riding frigid tsunami waves filled with chunks of ice turned out to be more difficult than expected (). They had several near-misses, in which chunks of glaciers nearly hit them. In retrospect, McNamara admits “it was not a good idea.”

“He’s almost naive, to an extent, as to how gnarly some of the things he does are,” says Little. “I’ve seen him do things that are just stupid and come up smiling.”

The secret, though, is that McNamara actually enjoys it. “I love getting pounded,” he likes to say. “It makes me feel more alive.”

His current tow partner, Andrew Cotton, a shy, sandy-haired Brit who works as a plumber and lifeguard to support his surfing, told me a story about a particularly bad wipeout that McNamara took at Nazaré, where he got hit by two waves in a row, right on the head. “He finally surfaced, after probably the most horrific wave on the head I’ve ever seen, and he had a big smile on his face,” Cotton says. “There’s just something not quite right about it. There wasn’t an ounce of panic. That wipeout for him was just as good as catching a wave.”

“It’s calculated,” McNamara says, at last dropping his speed below 100 mph. “It’s a calculated crazy. The only safe plan is don’t go.”

To moderate the risk, he embraces new technology, such as the he wears under his wetsuit—and, more controversially, a self-propelling surfboard called the . Core surfers detest the WaveJet, but McNamara views it as a useful tool for beginners or handicapped surfers. He also uses it himself, as he did one day in December 2012, on a swell at , a frightening break that lies 100 miles off the coast of San Diego.

On December 21, McNamara went for a wave at the same time as , who was paddling. They both wiped out, but while McNamara popped right up to the surface, thanks to his vest, Long’s vest malfunctioned and he was held down for three waves, a horrifyingly long time. He was brought to the boat unconscious. “There were a few moments there when I was no longer spiritually present in my body,” Long says now. “It was wild.”

Many reflexively blamed McNamara for dropping in on Long, one of the most beloved icons of the sport. Few were aware that McNamara’s safety team brought oxygen and a stretcher to help stabilize Long. “People drop in on each other all the time, and nobody makes a big deal about it,” McNamara sighed to me one night at dinner. But when it’s Garrett McNamara, the “cowboy,” and he’s riding a WaveJet, then it’s a big deal.

[quote]A local bodyboarder first reached out to McNamara. “To my parents and grandparents and uncles, who were all fishermen, that beach was a place of death.”[/quote]

Long doesn’t fault McNamara for what happened. “Straightforward, Garrett is one of my friends. He was before and he still is,” says Long. “In no way do I blame him for what happened in my accident.”

The fact remains, though, that McNamara is out of sync with his fellow big-wave surfers. As people like Long and Dorian have reverted to paddling big waves, emphasizing human power and style over sheer size, McNamara continues to rely on towing into ever bigger challenges.

“He’s just marching to his own drummer,” says Sam George. “He doesn’t walk along in step with the current big-wave vogue.”

McNamara himself thinks the criticism has more to do with sponsor envy than core surfing values—and the fact that he, of all people, is the guy bringing mainstream attention to big-wave surfing. “They all want it so bad,” he says. “Don’t let ’em fool you for a second.”

McNamara continues to insist that he split with Billabong because of the alcohol sponsor, a point he reiterated during his Lisbon Q and A. He told the audience that “nothing I’ve achieved in my life has ever come about because of alcohol.”

He must not have been thinking about his wife, Nicole, whom he met with a significant assist from Señor Tequila. They were in Puerto Rico in April 2010, where she was competing in a paddleboard race and he was attending an event for , a group that introduces autistic children to the water. At a banquet, he kept staring at her. “It was love at first sight,” he says now.

At first she brushed him off as just another old guy on the make—she was in her mid-twenties when they met, McNamara was past 40—but he persisted, plying her with agave shots. By November 2010, six months after Puerto Rico, they were in Nazaré together as a couple. The situation was complicated considerably by the fact that McNamara was married but separated at the time, with an infant daughter and two older children back home in Hawaii. Nicole had also recently parted ways with her college sweetheart.

These days, Nicole wears several hats at once: She’s Garrett’s handler, wave spotter, agent, sentence finisher, and protector. They’re rarely more than ten feet from each other, except when McNamara is surfing. In the six days I spent with them, she was constantly on her laptop or iPhone, answering his e-mails and handling countless requests from sponsors and media. More than that, she channels his hyperactive energy and keeps him on track and in check. “I have two settings,” he said, “full speed and stop.” When he’s not surfing, Nicole tells me, he enjoys gardening. (She then bursts out laughing.)

In Nazaré, he was in full-speed mode. He’d been in training since August 1, when he weighed nearly 200 pounds. Now, on an alcohol-free, vegan-ish diet, he’s down to 175 or so, on a five-nine frame. He wakes up between three and five every morning and runs to the lighthouse to check conditions. If things look good, he’ll go surf or practice paddling; if not, he’ll go to the gym or do yoga, or both. He and Nicole eat lunch and dinner at on the beach, and the menu never changes: salad, “Garrett soup” (chickpeas and cabbage), and perhaps a bit of grilled local octopus. He doesn’t even drink coffee.

But the couple isn’t as tightly wound as this sounds. During my two stays, they invited me to their big first-anniversary dinner, and Garrett showed me the results of Nicole’s home-pregnancy test (it’s on!). “It’s a boy, I know,” he said, to Nicole’s eye rolls. Garrett was constantly pranking me, as well, stuff like calling my room in a fake Portuguese accent, pretending to be a hotel staffer. The fact that his voice sounds a little like Bill Murray in Caddyshack makes everything that much funnier.

The McNamaras do not get paid directly by Nazaré, but the town provides an enormous amount of infrastructure and support, starting with three brand-new, four-stroke Yamahas, plus a warehouse to store them in. The point of the is to publicize Nazaré’s extraordinary waves—and, town officials hope, to draw more visitors during the winter season.

Like many other fishing villages, Nazaré has suffered from the decline in global fish stocks. As the industry sagged, Nazaré missed out on the upscale tourist development that transformed the Algarve region to the south. There are a few dated hotels, and some locals rent out rooms to tourists, as they always have, but the vibe is more like Asbury Park with a bullring than South Beach. The beach itself is wall-to-wall during the summer, but in winter the place was usually deserted. “The town was empty when we first got there,” McNamara says.

By the time I showed up last November, that was no longer the case. Even without a swell, there were tourists in the cafés and walking along the beach. The Project had grown considerably, with sponsorship from a national cable company, Zon, which broadcasts McNamara’s exploits whenever he’s in the country—about three months a year.

Now they were trailed by an entourage of photographers, safety and logistics people, a publicist, and a fleet of logoed vehicles. The Portuguese navy had long ago dropped special wave buoys in the canyon, which allow McNamara to measure the size of the swells. When he went back to Hawaii during December and January, he monitored the buoys and weather patterns from afar—and had a private jet on standby near New York if he needed to get back to Portugal fast. The Project has already paid off: By last January, anyone with access to CNN had heard of Nazaré and its giant waves. The arrival of storm Brigid made national news, and when I got to town on Saturday, February 1, there wasn’t a hotel room to be had for miles. Yet big-name surfers still stayed away, for the most part, remaining unconvinced by the wave itself. “It’s really a novelty wave,” says Greg Long, reflecting a widely held view among surfing’s big guns. “It stands up tall for half a second, and then it’s over with, so there’s no real ride.”

“It will look incredibly huge in a still photograph, because it is—for a few moments,” agrees Sharp. “But over the course of the wave playing out, it tends to lose some of its size. That’s a conundrum for evaluating its height.” The Billabong panel judged McNamara’s 2011 wave to be 78 feet high, exactly one foot taller—no more, no less—than the previous record.

Not everybody downplays the wave, though. , a South African surfer who won this year’s big-wave contest at , believes that McNamara is on to something important.“It’s a ginormous wave, and it’s brought new attention to big-wave surfing,” he says. “That’s what we all want to do—find a new wave and break records. And Garrett went out and did it. And yet there’s all this negativity around him, and I don’t know where it comes from.”

Nazaré commands a bit more respect from those who’ve actually been there. “It’s a fun and exciting wave when it’s small,” says Kelly Slater, who surfed there before McNamara ever showed up. Two years ago he came back, and McNamara towed him into some 30-footers. He was impressed. “It’s terrifying and bizarre when it’s big,” Slater says. “You can quickly get yourself in a bad situation there. The place is a freak of nature.”

[quote]“McNamara's just marching to his own drummer. He doesn’t walk along in step with the current big-wave vogue.”[/quote]

One problem is that conditions are often sketchy, which makes for dramatic photos but risky surfing. In late October, Red Bull surfer Maya Gabeira, one of the few female big-wave riders, . After she was rescued by her tow partner, Carlos Burle, he went out and caught a wave that was said to be—wait for it—the biggest wave ever surfed.

The jury is , at least until this year’s Billabong awards, on May 4, but others have run into trouble at Nazaré—including Shane Dorian, who flew over in January 2013 for a paddle session on a pretty big swell. In a , Dorian described the Nazaré surf as “super challenging” and said, “If you paddled into the biggest wave today, it would probably be the biggest wave ever paddled into.”

“He got his ass handed to him,” says McNamara.

“You can’t ever feel really comfortable over there,” says the Basque big-wave rider Axi Muniain, who surfed Nazaré in January 2013 with Jerome Sahyoun and took a high-speed, tomahawking biff that earned him a Billabong nomination for . “You have to be pretty crazy to surf there all the time.”

The next morning, I see what he means. Leaving McNamara and his team at the harbor, I ride over to the lighthouse with Nicole and Paolo Salvador, a squat, muscular local nicknamed Pitbull who’s in charge of safety for the Project. We enter the old fortress at the point and climb up the nearly 500-year-old stone steps to the roof, where the lighthouse sits. Nicole’s job is to spot the waves, while Pitbull directs a crew on the beach below that includes firemen, a quad, an ambulance, and a tractor.

The cliffs and hillsides are already packed with spectators, thousands of them, all focused on the ocean, which rages with a fury like I’ve never seen before. Enormous, angry swells are thundering in from the north, and when they meet the canyon swells, they form huge peaks that break 200 yards or so from the rock in front of the lighthouse. The rock is roughly 60 feet high, and it’s getting buried by wave after wave.

It looks like unsurfable chaos. Mammoth waves are breaking at right angles to each other, sending whitewater churning in every direction, like the most savage avalanche you’ve ever seen. Inside, I see what looks like a square mile of whitewater, tinged the color of cappuccino foam. This is the most dangerous place, because the jet skis lose traction in the bubbly, aerated water; meanwhile, a rapid current will drag any swimmers directly toward the rocks. This is where Gabeira got in trouble. “If someone falls in the wrong place, they might not come home,” McNamara said the night before. My knees are wobbly, and I have to sit down.

Earlier, McNamara himself dismissed his supposed 100-footer from 2013. “It wasn’t a world record,” he said over dinner. “It was a mush burger.” He wants Big Mama, but will she show? It seems likely. The swell that produced his “record” wave measured 5.9 meters on the navy buoys. These register close to nine meters, which means the actual wave heights will be that much higher. “This is the biggest we’ve seen it,” says Nicole.

Finally, three jet skis emerge from the mouth of the harbor, about a mile away. They’re having a tough job just getting out, laboring up the wave faces and then smashing down into the troughs. Two fishing boats are having a worse time, taking waves over the bow almost as soon as they pass the jetty.

McNamara had spent the previous day preparing his gear, including a —sleek, silver and gray, and emblazoned with the logo of his newest sponsor, Mercedes-Benz in Portugal. The board came with a striking silver Mercedes helmet and was supposedly created by Mercedes engineers in Germany, but actually it was made by a deaf Portuguese shaper based outside Lisbon. Unlike most tow boards, which have a lead weight bolted between the rider’s feet, this one has the weight embedded inside. It is a bomb and a thing of beauty.

McNamara is also carrying a phone in his wetsuit, equipped with sensors and software that record his speed, height, and body position in the water. It will measure his track on the wave: velocity, drop, even the angle of pitch and roll, all in three dimensions and real time. This is science-show cool, and it could help lay to rest any doubts about the height and overall gnarliness of the Nazaré wave.

But so far this morning, things have not gone smoothly: Even before the jet skis left the harbor, one of them stopped dead, probably because it inhaled a piece of floating trash. The ski was hoisted out and towed back to the shed, where McNamara crawled under it, grunting as he pulled out bits of plastic netting with pliers.

Now at last they were under way. From the cliff we watch them battle the swells, until they reach the relatively calmer waters of the Canyon, where they cluster together and confer. Today’s game plan is simple: Go for Big Mama. No inside stuff, no tube rides, just the biggest wave.

The previous night, I asked Nicole if she thought Garrett would ever slow down, given that he’s about to become a dad again, at age 47. She thought for a moment and said, “Maybe if he gets his big wave tomorrow, he’ll start thinking about it.”

Whether he’d get his wave was an open question. Big Mama is out there, but she seems cranky today. Rows of enormous swells are lined out to the horizon, rearing up into giant faces when they reach the canyon edge. But they’re breaking sloppy. We watch the jet skis zip around, looking for a rideable wave. They tow into one, then another, but neither breaks. This goes on for an hour, then two. Frustration builds.

“They’re standing up, standing up, standing up—but then they’re not doing anything till they crumble on the inside,” Nicole says into the radio.

“Patience,” says Pitbull.

“What’s that?” Nicole asks sarcastically.

Actually, Cotton tells me later, McNamara seemed calm out there, which was out of character. “He was really mellow in the water. He said, Take your time, let’s not rush this. Let’s wait for the right wave. He’s not usually like that.”

Finally, around 10:30, Nicole spots a set of three waves that stand up taller than all the others. Cotton is on the tow rope, and McNamara zooms across the channel and slings him into the third wave, even as it’s still building. From the cliff we watch Cotton ride, a tiny dot ripping a seam into the face of the wave. He’s going extremely fast, slamming over the chop, but the wave is moving faster, and the peak topples over into an avalanche of whitewater that he cannot outrun. The dot disappears.

“Garrett!” Nicole shouts into her radio. “Cotty’s down!”

[quote]“I was just barely hanging on, because it was so bumpy, and there was nothing smooth about it. I didn’t come out thinking I’d properly surfed it.”[/quote]

The jet skis swoop in and converge on a tiny figure bobbing in the foam and whisk him to safety. Now it’s McNamara’s turn on the rope. A few sets later, Cotton flings him into another huge wave that builds to a foamy crest—but somehow doesn’t break. This one is moving even faster, and the anticipation mounts as McNamara hammers down the face, until he finally turns out over the wave’s right shoulder and the crowd sighs.

After another hour, they decide to call it. It’s getting too windy, and the swell direction is not quite right. Instead of heading for the harbor, McNamara guns it for the beach, threading his way in between huge, dangerous breakers and then zinging his jet ski up onto the sand. He climbs off, grabs his Mercedes surfboard, and climbs up over the rocks toward the lighthouse, looking like a knight in his silver helmet. Spectators rush down to meet him, and he spends the next 45 minutes lost in a sea of people, shaking hands, taking photos, giving quick sound bites to one TV crew after another. “He enjoys this part,” says Nicole as we wait patiently.

Finally, he makes it to the car. He throws the surfboard in back, gets in the driver’s seat, and exhales deeply.

“Big Mama was a cock tease today,” Nicole says from the backseat, and he laughs.

After McNamara leaves, the crowd on the cliffs thins out a little. But not completely. As the afternoon wears on, hundreds of spectators remain rooted to their spots, still watching the waves. In town the promenade is thronged with onlookers, closed to cars because the water is coming up over the road again. At the north end, a front loader is dumping sand on the beach in a futile attempt to slow the advance of the sea, but it’s not working.

The main show is on the beach, where 20-foot breakers are smashing the shore. The town shakes from the force of their impact. Farther out, even bigger waves rear up and smash on the rock in front of the lighthouse. It’s enough to draw out the denizens of the dark, smoky Bar Galé, an old fishermen’s hangout on the beach. The men line the sidewalk, holding their glasses of double-bock beer and squinting into the sun as the waves pound endlessly.

Back at the harbor, strip out of their wetsuits and change into street clothes. Pitbull and his crew help wheel the jet skis back to the garage and rinse off the salt water. There’s a quiet heaviness in the air, a feeling of vague disappointment; they spent five hours on the water and caught two waves, only one of which actually broke. Cotton digs for his cell phone and studies it intently, looking at photos of the session in Mullaghmore, Ireland, that he skipped so he could ride one wave at Nazaré. Shoulda gone to Mully, he thinks. He texts his wife that he’s back safe.

Then a local photographer named Pedro Miranda arrives with good news. He takes out his phone and passes it around. On it is a shot of Cotton’s wave, and it doesn’t just look huge: It’s death-defying, the surfer a tiny dot about to be swallowed by a maelstrom of white-water. The relative size of the spectators in the foreground makes the wave look that much bigger, as does the distance—Miranda was shooting from the top of the hill, at least 200 yards above the lighthouse. Foreshortening and perspective and cropping help make the scene look even more dramatic than it already was.

McNamara moves in for a look. His face brightens. “Hey, Cotty!” he shouts. “You got the wave of the day!” Cotty breaks into a half-smile.

Within hours, Cotton’s ride will make news around the world. In England, a headline in The Daily Mail asks, “?” The journalistic consensus is that Cotton’s wave was 80 feet tall, though based on what, nobody knows. In the photos, it’s almost impossible to see the bottom of it.

Nevertheless, the video goes into heavy rotation on CNN, and the taciturn Cotton will be interviewed a dozen times by the BBC and other international media. Even better, he will learn that his ride has been accepted into the running for this year’s Billabong XXL biggest-wave award. It’s a breakthrough in his career, at age 34.

“I don’t think my wave is a world record,” Cotton tells me later, modestly. “One, I fell at the bottom; and two, Garrett’s [world record] wave broke top to bottom, and if you look at mine, it just sort of crumbled. And number three, that wave for me, I was just barely hanging on, because it was so bumpy, and there was nothing smooth about it. I didn’t come out thinking I’d properly surfed it.”

But the data suggests that the waves were world-class. The sensors in the phone in McNamara’s wetsuit recorded a drop of 55 feet, from the beginning of his ride to the end, and a top speed of 40 miles per hour—yet he never came close to reaching the bottom of the wave. Cotton’s wave was much bigger. Still, it wasn’t Big Mama. She’s still out there.

Late that night, the wind kicks up, lashing the village with rain and beating against my hotel-room window so hard that it wakes me from a sound sleep. Then comes a knock at the door. It’s McNamara. “Are we going running?” he asks, eyes blazing. “I’ll be waiting downstairs.” He trots down the hall.

We drive to and park on the beach. It’s bleak and forlorn, covered in storm trash and raked by a vicious wind. We start running toward the lighthouse on the wet sand, but our way is blocked by waves, so McNamara finds a trail snaking up through the grass and bamboo in the dunes. Emerging above the lighthouse, we drop down into the lower town, which is just stirring awake, and make our way through a maze of tiny streets.

It was freezing on the beach, but now we’re sheltered from the wind, and McNamara strips off his shirt to reveal a body that’s more aging rugby player than surfer god. He hauls himself over a whitewashed cement wall and I follow, dropping down only to realize that we’re at the bottom of the funicular railway that connects the lower village with the upper town, several hundred vertical feet above us. I’m pretty sure this is illegal.

“I did this every day the first year we were here,” McNamara says, and starts trotting up the steep incline.

In summer, the trains ferry tourists to take in the view from the top of the cliff. But now it’s off-season and the train cars are parked, home only to a clan of stray cats who flee at our approach. There are numbers written on the concrete, and McNamara stops at the 30-meter mark and looks back. “Thirty meters,” he says. “This is what a 100-footer looks like.” He keeps going, slow and steady, climbing high above the town, past the second car parked near the top, and then finally to where the track disappears into a tunnel in the cliff.

He climbs up into the tunnel, then turns and drops into his surfer’s stance. The tunnel arch frames a view of the whitewashed town and the beach beyond. It’s like he’s in the tube, the train tracks dropping away from him like the face of a huge wave. “This is how I see the barrel of Big Mama,” he says, swaying to stay on his imaginary line. “I’ve ridden it a hundred times in my mind.”

Bill Gifford () is an ���ϳԹ��� contributing editor.