IT’S SNOWING AS we pull our van onto a muddy turnoff on a two-lane coastal highway. With a gloved hand, Pat Millin wipes fog from the passenger-side window and studies the rugged shoreline of the Lofoten Islands, the southern portion of a remote archipelago in northwestern Norway. On the horizon, a storm is pitching 20-knot winds across a gray and tattered ocean. Fifty yards below us, waves lurch and fizzle against the black rocks of the bay’s breakwater.

Surfer Pat Millin

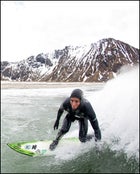

Pat Millin surfing the Lofoten Islands

Pat Millin surfing the Lofoten IslandsMap of Norway

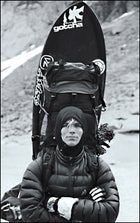

Surfer Matt Whitehead

Aussie surfer Matt Whitehead

Aussie surfer Matt WhiteheadSurfer Christian Wach

California surfer Christian Wach

California surfer Christian WachArctic surfing, Norway

A team member picking his way toward a spot the group christened Glacier Bay

A team member picking his way toward a spot the group christened Glacier BaySvartisen glacier, Norway

Like ice: Svartisen, Norway's second-largest glacier

Like ice: Svartisen, Norway's second-largest glacierSurfer Christian Wach

Wach on the beach at Broken Hearts

Wach on the beach at Broken Hearts“That’s surfable,” declares Millin, a 22-year-old pro surfer from San Diego. He pulls a wool cap down over his ears, takes a deep breath, and throws the door open. Through the whistle and thump of freezing wind, I can hear him yell, “I’m going in!”

The ocean doesn’t look even vaguely surfable. Millin knows it, but after ten straight hours of creeping over ice-covered roads with our photographer and expedition leader, Yassine Ouhilal, we’re desperate. We didn’t travel 5,000 miles to sit in a van and drink $7 cups of carry-out coffee (the going rate in Norway). We came to surf above the Arctic Circle.

A few minutes later, Millin and I are outside, shivering naked as we try to push bare feet into snow-flecked wetsuits. “This is stupid,” I protest through chattering teeth. “Too late now,” Millin smiles. Then he grabs his board, jogs off toward the exploding ocean, and dives in. I wade in behind him, jolted by the electric sting of 40-degree water seeping onto my skin. I watch as Millin drifts south toward the mouth of a 30-story fjord, his torso bobbing on the monochrome horizon. As we fight the current, I can feel the pull to open sea.

“Let’s go back!” I shout. Millin nods. Since we got out here, the winds have picked up and the snow has turned to M&M-size balls of hail. We can’t even see the shore.

Millin turns and paddles into the rumpled face of a wave, stands, and rides to the inside of a submerged reef before disappearing up the breakwater. I try to follow, but I’m swallowed by an errant wave and thrown into whitewash. We slosh out and run through snow back to the van, both of us with ice-cream headaches and brick-numb feet and hands. Key in ignition, heater full blast, a wrap of a blanket, an exhale, and a rev of the engine and we’re back on the road to another beach.

“There are some world-class waves along here,” says Ouhilal, who stood by the van and took pictures. “We just need to keep searching.” Through the passenger window, I watch as the ocean disappears in a static of snow. Like a TV screen losing its signal, it slowly fades and then it’s gone.

WE AREN’T MASOCHISTS, and we didn’t come to Norway just to be cold and miserable. We were drawn to these coasts, at 68 degrees north, to hunt for what could be the most perfect, undiscovered cold-water breaks on earth.

Ouhilal, a 32-year-old surfer and photographer based in Nova Scotia, learned about them three years ago, during his first expedition to the Lofotens. The pictures he brought back revealed a kind of tropical paradise in reverse, where warm sand was replaced by snow, crowded piers by ice shelves, and ribboned, ten-foot waves broke beneath an otherworldly curtain of aurora borealis. It looked like Hawaii stuffed into a freezer.

Our plan was to scout a few Lofoten breaks, head north into the unsurfed territory in Troms County, and then, if time allowed, explore the coast of Russia. (We eventually made it to Russia but weren’t allowed to surf; as we found out, most of the country’s northwestern Arctic coast is off-limits to anyone not in the military.)

Though swell charts for Norway showed that wintertime produced the biggest waves, it seemed suicidal to try surfing there during the darkest, coldest Arctic days. So we decided to go in early spring, when swell activity was still strong (albeit inconsistent), days were longer, and temperatures were, by Arctic standards, bearable: between 20 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Last April, heading out from various points of origin, we packed long johns, wool socks, ChapStick, and 30 pounds of cold-water surf gear into our bags and headed north. Way north.

Flying in to the Lofotens from mainland Norway is reminiscent of the prelude to Fantasy Island: There you are in the backseat of a prop plane, plunging through low-hanging clouds, between mountaintops, and over gaping bays of translucent-blue water. Through the tiny window, the spiky volcanic peaks of the surrounding fjords look like an EKG readout against the horizon. There’s a clunk on the frozen runway and minutes later you’re standing in the snow with a surfboard under your arm, wondering if this all isn’t a terrible idea.

At least that’s how I felt after Ouhilal picked me up at the airport and we took a bayside road to a cluster of 150-year-old converted fishermen’s shacks set on wooden stilts above bay water in the village of Ballstad. This 700-person town sits on the island of Vestvågøy, the center of five principal Lofoten islands that hug the coast of Norway like an open parenthesis. These cabins would serve as our base camp for the next few weeks.

THAT NIGHT, around a worn table in an adjacent lodge, I met the other members of our crew. To my right was Millin. Next to him was mop-haired Christian Wach, 20, a professional longboarder from San Clemente who last year was named by Surfer magazine as one of the top 100 young surfers in the world. Sitting across from them was Matt Whitehead, a dreadlocked 29-year-old vegan soul surfer who literally lives under a bush outside Byron Bay, on the east coast of Australia. While a group of fishermen drank beer and stared at us from the high chairs of a bar, we pored over a map and plotted our month-long course.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

Ouhilal wasn’t the first person to try surfing here. Forty years ago, a local character named Thor, inspired by the cover of a Beach Boys album, built a foam-and-resin surfboard and paddled out from the fishing bay of Unstad, along the western coast of Vestvågøy. For years he surfed, mostly alone, during the long, temperate, and small-wave days of summer. In 2007, photographs of Unstad’s enormous winter waves started hitting the international surf radar, and interest grew in Norway and beyond. A dozen locals bought surfboards and six-millimeter wetsuits and began exploring this wonder in their backyard. Before long, they were hooked. Here was a heaving point break that threw a 100-yard-wide, double-overhead tube across a reef and into the white-sand bottom of the bay. And nobody was on it.

Millin had surfed Unstad in 2007 and claimed it was his new favorite wave but very unreliable. A Rip Curl team found that out the hard way in April 2008. For two weeks, the group sat in their fishing cabins, shivered in the sleet, ate cod soup, and waited for the waves to come. They came, but only at the end of a very long wait. Norway, they said, was too fickle to surf; worse, it was freezing.

That may be true, but we’d come to find out for ourselves. To keep us warm on land, we brought base layers and down jackets supplied by Eddie Bauer First Ascent, which sponsored the trip. To survive in the water, we used the warmest wetsuits we could get. Ten years ago, spending hours surfing in 30-to-40-degree ocean water wouldn’t have been feasible. Old-school wetsuits, made with thick layers of synthetic neoprene, were cumbersome and leaky. If they were built thick enough to keep you warm in the coldest conditions, they were too constricting to allow a full range of movement. In recent years, design improvements in neoprene and the mass-market availability of products like geoprene a wetsuit material, made from limestone, that’s more water-impermeable than neoprene at half the thickness have changed the game.

That doesn’t mean it feels good. Your exposed face still stings, your head throbs after each dunk, and your toes and fingers go numb after about 30 minutes, no matter how thick your gloves and boots are. You have to want it. But why would you?

“I guess it’s the isolation. That’s why I wanted to come back here,” said Millin, slurping down a cod tongue at the lodge, grimacing, then slurping another. “How many people are surfing in Hawaii right now? How many thousands?”

Wach nodded and took a sip of beer. “The coldness, the snow you know, it feels purifying,” he said. “And to think you can be out somewhere alone, surfing on this sick beach. There are so few places on earth you can do that today.”

THE NEXT MORNING at 6:30, we loaded our boards in the van for our first trip out. “Cod jerky, anyone?” Millin asked as he cued up a techno song on the stereo.

“Meat is murder, mate,” Whitehead said. “And this crap music is murdering my ears. Turn it down.” Millin playfully turned it up and jammed a handful of salty dried fish into his mouth. Meanwhile, Ouhilal kept his eyes on the ice-covered road, which he traveled at more than twice the speed limit, determined to make the outgoing tide.

I couldn’t help but think that we were all going on a blind date arranged on the Internet. The satellite images, logistics, and statistics printed from the Web and crammed inside a manila folder on the van’s dashboard provided a stunning data portrait of our destination, but those things meant nothing until we actually got a feel for the place. That’s what had attracted Millin, Wach, and the rest of us to this snow-globe landscape: the nervous, giddy feeling of expectation, of finding some icy Waimea here in surfing’s last frontier.

Waimea it wasn’t. During our first week, we surfed microscopic, wind-blown shore breaks along the Lofotens’ central-western coast. For a few days, the weather was so bad we stayed inside and played guitars and drums we’d borrowed from a local death-metal band. The next week, we hiked three miles across a fjord to camp on the frozen sand of a crescent bay. It was so cold that residual water in Millin’s ear crystallized overnight and expanded in his ear canal. He woke up yelling, holding his head over the fire to try and melt it out. On the two-hour hike through blizzard conditions back to our boat, I swore I could hear the sound of Odin’s voice through the whipping wind, saying, “Go back to California, fools.”

Yes, there were dozens of perfectly set-up beaches in Norway. Yes, it was the most stunning place we’d ever seen. But after two weeks and a thousand miles of searching, a cold reality was setting in: The waves sucked. Inclement weather seemed nearly constant, and on most days, gale-force winds and random sleet and snowstorms churned the ocean into a frothy mess. Through it all, we’d managed only a handful of sad sessions. On our twelfth night in the Lofotens, we gathered around our table, ate our nightly meal of cod, and debated a new plan of attack.

A local map showed a place called Senja, an island north of the Lofotens that looked promising. There, in Troms County, the fingers of fjords jut into the Norwegian Sea and protect the shores from northern wind. Up there, we’d simply have to find surfable waves. And, unlike in the Lofotens, most of the coast in Troms is accessible from a state highway, which would let us stay in constant view of the ocean. When the swell turned on, we’d pull over, suit up, and jump in. Based on Ouhilal’s research, it appeared that nobody had surfed Senja before. We left that night.

To our surprise, we found that even in April much of the Troms highway is banked by five-foot walls of snow. When there aren’t snowbanks, there are tunnels, and traveling along this road makes you feel like you’re being pushed through a series of pneumatic tubes. The windows of the van flashed with blue and white, displaying, at one moment, a white wall of snow and, the next, impossibly stunning fjord peaks, neon-blue skies, or another perfect beach…tons and tons of beaches.

“My God, I think we found what we were looking for,” Ouhilal said as we passed yet another setup. “This place is a goldmine.”

After 12 hours, we reached the northwestern end of Senja, near the village of Hamn. We pulled over around 3 P.M. and gazed at a crystal-clear bay, where a corduroy of tiny, perfectly formed waves rolled in, arched their backs in blue waters, and crumbled in white lines on the shore. On the beach, the tide lines of the last storm swell were still frozen in the sand. By measuring wave lines, Ouhilal was able to calculate that five-foot waves had broken on this beach, probably just days before.

“This place could be amazing,” said Whitehead, pushing his blond dreadlocks from his eyes as he stared out at the ocean. Around the fjord, another perfect setup revealed itself on the next beach, and the next. After a while we stopped counting.

That night, Whitehead suited up on the dirty snow of a shipping channel and paddled out to the side of a blinking buoy that marked a shallow reef. Even with a complete lack of swell from the north and south currents, every few minutes a three-foot wave was breaking on the reef with the incoming tide.

It wasn’t a great wave it wasn’t even a good wave but it was rideable, and that was enough. After paddling out at 10 P.M., with the last vestiges of sunlight pouring into the navy-blue sky, Whitehead became the first person (on record) to surf Senja. In honor of the blinking buoy that kept him company, he named the break Discos.

WHITEHEAD IS WELL PRACTICED at doing bold things in tough settings. While traveling in Mexico a year before, he’d lost his money. So he found a bike, strapped his surfboard to it, rode from Mexico City to Austin, Texas, hitched to Colorado, flew to New York, and then rode to Nova Scotia. Throughout the year in Australia, he spends “usually two or three months” working as a plumber, to earn travel money, and the rest of the time surfing, reading, and sleeping “eleven and a half hours a day.” That sleep total might make you think he’s lazy, but he was the most vigilant surfer of the group, paddling into freezing water in a leaking wetsuit, without complaint.

His tenacity was matched by Ouhilal’s hunger to find new waves. The next morning, on the drive back to Ballstad, Ouhilal took a sharp left off the highway leading to the Nordland coast. As we rolled along, he stopped at every bay inlet, every tip of a fjord, any spot that was potentially surfable. “You have to learn to be a visionary, to see things that people don’t,” he said, snapping photos of the coastline. “What I’m doing mostly is reconnaissance, taking pictures, plotting when to come back.” In the three weeks we spent in Norway, Ouhilal took upwards of 35,000 pictures and drove nearly 6,000 miles.

While driving, he ate constantly. The first week, the crew watched in amazement as he consumed almost a pound of chocolate in a single half-hour sitting. Most nights he didn’t sleep but instead pored over the forecasts for the region, scanning Google Maps for possible surf. On the trip up to Senja, he unexpectedly woke us all at 1:30 A.M., after we’d slept less than two hours, and announced we were heading out. Millin and Wach refused to go, leaving just Whitehead, me, and him for that leg of the expedition.

This insatiable drive occasionally pays off: Ouhilal has pioneered a number of Arctic surf breaks in Norway, Iceland, and Canada, and he’s one of the top cold-water surf photographers in the world. But it comes at a price. He’ll get the shots, but he’ll make your life hell in the process.

Ouhilal shrugs off any gripes. “You need determination to do this, and you need to know that 99.999 percent of the time you aren’t going to find a wave,” he said on a particularly miserable day during the trip’s first week. “A lot of people can’t handle that. I’ll just find some other hungry surfers who can.”

IT’S ABOUT 9:30 P.M. on the trip back from Senja to Ballstad; twilight has put a dark-blue lens on the sea and snow. By late April, the sun never really sets but skims along the horizon, following you at daytime like some ever-present spotlight. By night it becomes the red stagelight of a nightclub, bathing the sky in moody hues of blue, purple, and dark orange.

We’ve been driving for 14 hours straight. Just as we’re about to give up on surfing for the day, Whitehead spots the fluorescent lines of whitewater squiggling into a bay. Ouhilal stops the car on the roadside.

“Yeah, that’s surfable,” he says. Whitehead jumps into the backseat and rustles through the nest of wetsuits. Minutes later, he vanishes into a thicket of thorny bushes and bounds down the snow-and-moss-covered rocks that lead to the beach.

By the time Ouhilal and I make it to the clearing, ten minutes later, Whitehead is paddling for his first wave, a neck-high point break that lazily arches its back along an exposed black-rock reef and then catapults him down a wall of glassy water. I watch as he rides a few feet in front of me, the wave’s face reflecting the crescent moon before it shoots him into inky blackness.

For this session there are no cameras, no poses, nothing to prove. We’re just three people floating in the Arctic Ocean, surfing a wave that’s been breaking alone for tens of thousands of years. We’re the first to feel its shape, trace its movements, be a part of this big, marvelous, living thing. An hour later, as we pull ourselves from the water and retrace our steps back to the van, everyone is smiling. Whitehead names the break Broken Hearts, after a local Ballstad girl who shirked his advances last week. “To me, that makes it all worth it,” says Ouhilal. “To do this it’s a very special thing.”

A week later, Lofoten’s moody and wind-torn waters are transformed into ceramic smoothness as a new southern swell lights up the coast with dozens of waves, some pushing nine to ten feet on the face. Lofoten has finally granted us a peek at Norway’s true surf potential. It’s fickle, all right, but when it’s on, it’s like surfing nowhere else on earth.

A few days before leaving Norway, we go back to Broken Hearts with Millin and Wach and confirm with a local family that we are indeed the first to surf the break. A ten-year-old boy, Hans-Georg, watches us the entire time with wonder. He’s never touched a surfboard, and as we leave he begs us to come back. “The waves, now in spring they are so small,” he says. “Come back again. In winter, they are the size of the mountains.”