Surfing Your Way to Better Parenting

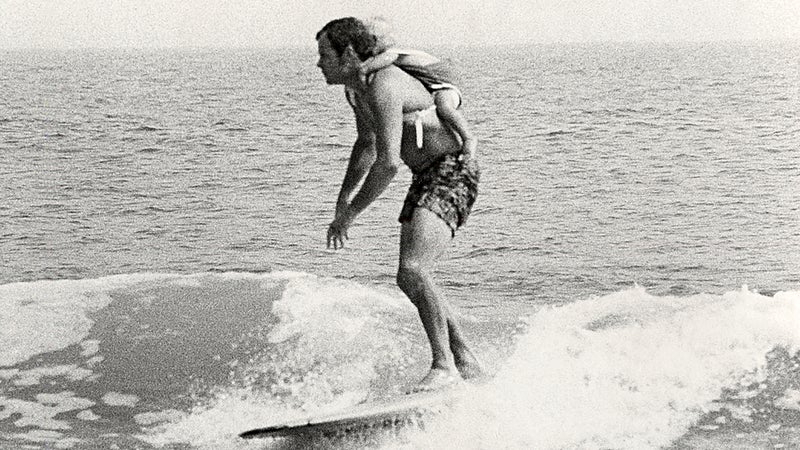

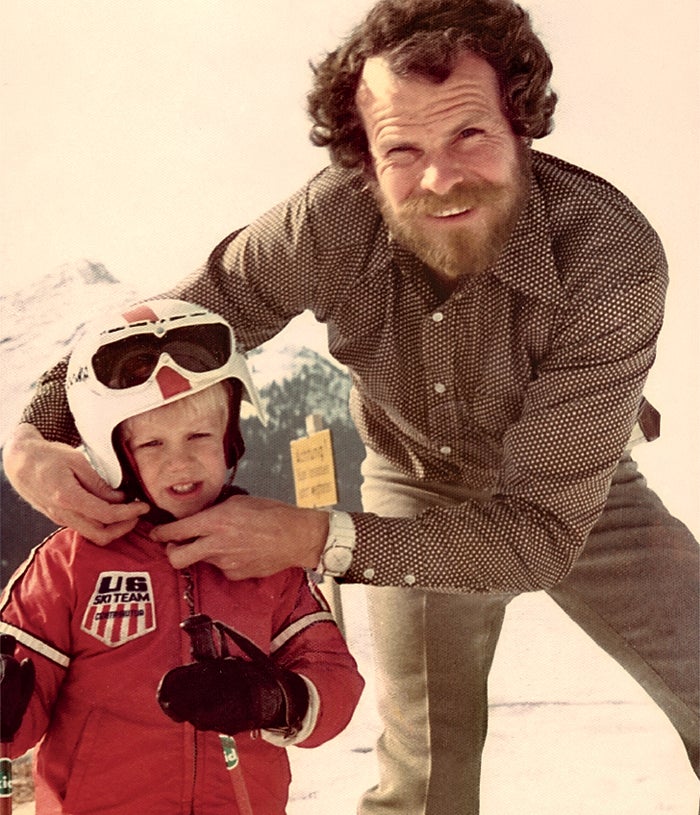

Norman Ollestad's father taught him to surf during rambling, tough-love safaris down the coast of Mexico. Then the education came to a sudden and tragic end. Forty years later, Ollestad heads south with his own son—and finds that the old road maps can only take them so far.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

My son and I tucked our surfboards under our arms and jumped off the last wooden beach stair. It was the first morning of our trip to a secluded point break in Mexico, a country I’d been surfing all my life, starting with the road trips my father took me on in the 1970s when I was a boy. We’d leave our home in Malibu and head south, driving for several days, crossing the Gulf of California on the ferry, and surfing all the good spots down to Puerto Vallarta, where my grandparents lived. Carrying on the tradition with my son, Noah, was important. When I was 11, my father and I were in an airplane crash, and he’d been killed. These trips with Noah, now 14, kept us connected to my father’s adventurous spirit.

My favorite spots as a kid—Sayulita and Punta Mita, close to my grandparents’ house—were now overcrowded, but a couple of years ago I’d lucked upon a long left point break in the mouth of the Gulf of California about 300 miles north of Sayulita. After two summers of surfing the point for a week with Noah, staying in the one small hotel with just a few friends and no one else, we couldn’t wait to go back.

The morning sun loomed behind the jungle mountains, and a single ray splintered through a notch, leaving us in shadow trotting along the horseshoe-shaped cove toward the point. Noah started whistling a song he’d just learned on his ukulele, “Sunshine of Your Love,” jutting his chin to the hard notes, rolling his shoulders and thrusting his pelvis to the beat. His loony sense of humor reminded me of a moment I’d had with my father in the surf somewhere south of here: I’d gotten my first deep tube ride, and emerging from the cavern drunk on adrenaline, I lost control of my body and flopped into the water; when I surfaced, Dad and I started laughing, and that’s when I finally understood why he got so wild-eyed about surfing and pushed me so hard—something I resented as a boy.

Noah and I stopped and watched the swells as they bent around the rocky point. As if on cue, each wave folded from the top of the point down into the heart of the cove, never overrunning the open face—a surfer’s canvas. There remained very few places on earth that offered shapely yet unpunishing waves like these without thirty or forty guys vying for them. This one was all ours.

The day before, while we were packing our boards, Noah declared, “This year I want to put a lock on my vertical snaps.” Translation: I want to master going straight up the face of the wave at its most vertical point, hitting the pitching lip, and snapping the board around in a tight arc.

I was surprised by the hard, steely glare in his eye. I’d never seen him so determined; it contradicted the passive kid who would give up a great wave coming right to him if another surfer wanted it—and would then moan, “I never get the good ones”—and who wanted to prove to the bullies that he wasn’t just a “pussy midget,” but still screamed in a high pitch whenever a big wave approached. The last time he was half this excited was when he’d told me that he loved skateboarding and I’d bought him a board for his birthday. But he mostly just sat on the sideline, watching his buddies practice, and when they advanced to riding a halfpipe, Noah was too scared to drop in and then decided to quit because “they’re so much better than me now.” What seemed to be missing most was his passion. His tentative personality made him an easy target for teasing, which meant that he needed that elusive fire a little more than most kids.

So when he put his hand on my shoulder and said, “I want to take my surfing to another level on this trip,” I saw an opportunity—and was already concocting a plan. This was the year Noah would blossom in the surf, and he’d start his freshman year of high school with a well of newfound confidence that would fuel his journey through adolescence. Even the offshore breeze, pungent with fruit trees, mangroves, and saltwater mist, seemed to foretell sweet success.

I had it all figured out.

“The waves look big,” Noah said, his neon blond hair lighting up in the rising sun.

Under a surge of adrenaline brought on by the surf, I strained to remain calm. “It looks perfect for you.”

He dropped the tail of his four-foot, ten-inch surfboard into the sand, staking it upright, and wrapped an arm around the nose like it was his teddy bear. It was the first tear in the immaculate picture of my son getting the rides of his life.

“The mosquitoes aren’t bad for July,” I said to deemphasize the swells.

He ignored me and scowled at the ocean.

Another blue gem peeled past us. It was hard to believe that the treasure I was salivating over might look intimidating to Noah, and I flashed to my father standing on a beach in Mexico, like I was now, watching his son struggle with fear.

“In the old days,” I said, casually stretching my neck, “when I’d come through here with my dad on our way down to Puerto Vallarta, we had no—”

“No air-conditioning,” Noah interrupted, his eyes never leaving the surf. His well-built shoulders—the only physical sign that he’d just turned 14 and was entering puberty—sloped to one side, mouth wrinkling with something sour. “I’m kinda scared,” he said.

My shoulder blades pinched together. What happened to the impetus behind “I want to put a lock on my vertical snaps”? Now I’d have to persuade him to take a leap over some wholly manufactured unease and convince him that it would turn out to be fun and rewarding. How could we still be having the same battle we had when he was five years old and I tried to get him to ride the whitewash a few feet from the shore.

Another blue gem peeled past us. It was hard to believe that the treasure I was salivating over might look intimidating to Noah, and I flashed to my father standing on a beach in Mexico, like I was now, watching his son struggle with fear.

It was the summer before my deep tube. I was nine, standing around a small fire we’d built one morning with Grandpa in the sand at Sayulita, having gathered rocks from the edge of the seasonal river that emptied into the ocean, cooking corn on the cob because the town’s one restaurant was closed.

“Do we have to go back to Punta Mita?” I asked my father.

“The waves are better over there.”

“Why can’t we just surf here?” I argued.

“You’ve surfed Sayulita a hundred times, Ollestad. Let’s get you into something that has some speed and power.”

“But I like these waves.”

He glanced at the ocean, and his shoulder blades pinched together. “I don’t want to waste a golden opportunity,” he said. “Vamanos.”

I ate my corn and shooed mosquitoes in the backseat of Grandpa’s orange VW jeep, called a Thing, and we crossed a stream and climbed a steep hill, and the tires spit out dirt behind us. I hated always having to surf or ski where Dad wanted instead of where I wanted. We always had to do things his way, even if I was scared, and I didn’t care about “golden moments” like he did. It made me want to quit surfing altogether.

Punta Mita was littered with white shells, and I was terrified of the jagged reef where the waves broke. “I don’t want to surf,” I protested, but my father picked me up and plopped me down on my surfboard, pushing me ahead of him across the shallows.

“These waves are no sweat, Ollestad. Just bend your knees on the drop,” he said, as if it was that simple.

I scoffed with anger, tears in my eyes, determined to find some way out of this.

The surf was only three or four feet, but when I dropped into my first wave the trough was sucking off the reef so hard that I was thrown onto my back foot and my board got pulled up the face and over the lip, flinging me into the air.

If I hadn’t landed on the back side of the wave, I would have hit the coral, and now I was really pissed at Dad. But I paddled for the next wave so that he wouldn’t pester me about giving up. I missed it, though, and that gave me a good idea: look like you really want it, but never quite catch one. That’ll show him.

A bigger wave rose up behind mine, and my father dropped in. He crouched into a ball and disappeared under the throwing lip. On his way back out he wore a delirious grin.

“Go for this one,” he said, gesturing to an incoming peak.

I oared for it, bending at the elbow to weaken my stroke, and as the wave began to slip under my board, something bumped the tail and then my father was shoving me into the wave. I had to jump to my feet or get pitched over the falls into the coral, and this time I absorbed the powerful trough with bent knees. Then the board was sucking up the face, and out of instinct I rotated my shoulders the other way, tilted the board onto the downside rail, and extended my legs, making an arc under the pitching lip.

“Nice turn,” my father said when I made it back out.

I was torn between anger and excitement, but I had to know: “Was there a lot of spray?”

He laughed. “Should we go back to Sayulita now?”

“No, I’m all right,” I said with a tinge of resentment, because I wanted to make another radical turn, and that meant he’d gotten his way again.

I heard Noah. “What are you doing?”

He was watching me stand in anguished contemplation, just like I’d seen my father do, and now when I looked up at Noah I knew what he was feeling—he wished he wasn’t afraid, that he was as gung-ho as his dad, and the disconnect made the fear even more aggravating, twisting him around into a tailspin.

At the same time, I was seeing Noah from my father’s point of view—it’s a golden moment for my son, so we’ll take it; the fear is a minor detail.

“Just thinking,” I responded.

Although I appreciated that he was comfortable enough to express his fear to me—as opposed to my apprehension with my father—it did not, in that moment, prompt any new insights as to what course of action I should take.

Then I heard my father’s assured voice in my head: Hustle him up the beach to the easy paddle-out spot. Don’t let him sweat it. After his first good ride, his fear will be a distant memory.

But it was countered by: Or he’ll kick and scream like he did last year, and we’ll begin the trip with him in tears, vowing never to surf with me again.

Dad's bullheaded approach wouldn't fly today, but the fact remains—he showed me how to endure adversity. After our plane crashed and he was killed, it was the act of going surfing that kept me from spiraling too far into the pain and confusion.

Holding two or more opposing ideas in your mind at the same time and still retaining the ability to function—that’s parenthood, I thought, paraphrasing F. Scott Fitzgerald, and then stepped toward the point.

“Where are you going?” called Noah.

“To the easy paddle-out spot where there’s no current.”

“I’m just going to paddle from here.…”

When I rode my first wave my hair was still dry. It was a hundred-yard zipper that offered three juicy lip-bashing sections. Twenty or so minutes later, Noah finally made it out beyond the rows of whitewash, but the current had swept him too far down the beach, to where the waves were crumbly and ill formed—not what we’d come all this way for. Bedraggled, arms hanging into the water, one side of his face slumped against his board, he was spent before he’d ridden his first wave.

Maybe I should have dragged his ass out with me? I heard a voice say.

After our day at Punta Mita, my father had gone home, leaving me with Grandma and Grandpa Ollestad. I wandered freely to the beach, to town, wherever I wished, and I missed my father, but it wasn’t so bad, because I didn’t have to surf unless I wanted to.

My favorite local playa was what Grandpa called Rock Beach, maybe a two- or three-mile walk under the tropical sun, and one day on my way there I found a burro. A rope was craftily harnessed around its neck, head, and jaw, and I led it down the cobblestone road that connected the beach to the highway. I tied the burro to a tree and swam around a cluster of rock slabs that stretched out to sea; a narrow opening ran down the center of the slabs, and when a wave came in it washed you through the corridor between the rocks and flushed you out the other end near the beach. I loved riding waves through the corridor, and I could only bring my board when Grandpa drove me. But now that I had a burro, I could bring my board on my own. After a couple of hours swimming, I untied the burro and walked it over to the embankment made by the cobblestone road climbing up the hill. From the embankment, I leaped onto the burro’s back—something I’d learned to do back home in California, riding my friend’s horse in the Rodeo Grounds next to where I lived on Topanga Beach.

The burro became my transportation, and Grandpa let me keep him in an empty lean-to near the house. For three days I had it made, riding each morning to Rock Beach, then going to town for ice cream and scaring up a game of tag with the local boys in the town square. Then one afternoon, as I was returning from Rock Beach, a burly guy in a truck pulled onto the shoulder of the highway where I was riding the burro. He yelled at me and pointed to the burros standing in the back of his truck, and I saw the brand, two letters on top of each other, burned into the animals’ haunches. It was the same brand as the one on mine. I kicked one leg over and slipped down, clutching my surfboard, landing barefoot on the dirt. He yelled at me some more and took the burro to the back of his truck, where he pulled out some wood and the burro slipped and bucked its way up into the back with the others. I watched the burro drive away and cried during the entire walk along the shoulder of the highway to my grandparents’ house.

You should have dragged his ass out two days ago. You blew it.

For the second day in a row, a tropical storm to the south had turned the conditions sloppy. “Did you see that carve, Dad? … How was that floater? … Did I get vertical on that one?” Noah had asked after each ride and then questioned me again back at our room. The waves were too weak to get much out of them, yet his need for validation forced me to feign enthused responses, lest he get down on himself.

With every gutless wave Noah rode, every Ping-Pong game and round of water volleyball and chocolate ice cream devoured while lounging in the common room, my patience wound tighter and tighter. We were with two other families and a few couples at the hotel, and Noah seemed to be spending more time hanging out with the girls on the trip than surfing. Watching him shoot the shit in the frothing jacuzzi while the sun set on the Gulf of California, I tried to put my frustration into perspective. It was so simple for my old man, I lamented. In his era, there was no pressure on him to reflect on what he did—he knew it was good for me, and that was enough. It’s a different world today, of course, and his bullheaded approach wouldn’t fly, but the fact remains—he showed me how to endure adversity and flourish in this world, and it ended up saving my life. After our plane crashed and my father was killed, I was left to fend for myself on the side of a steep peak in the San Gabriel Mountains, engulfed in a blizzard at 8,200 feet. By utilizing the skills and courage he’d cultivated in me through surfing and skiing, I was able to navigate the icy slopes, steep rock, and snowdrifts, and scramble my way down to a ranch house at the base of the mountain. In the days and years that followed, it was the act of going surfing that kept me from spiraling too far into the pain and confusion inflicted by what I’d been through and what I’d lost. And, going forward, it was that wellspring of passion my father had nurtured in me that got me through the hardest storms.

Maybe that’s why I was so tense about the surfing. I knew Noah would have to rely on himself one day—even if it would never involve the extreme circumstances under which I’d had to. I wanted him to taste the exhilaration of grasping, even partially, something that demanded his conviction and passion, as it would be a vital resource for the rest of his life. But when the moment had come, I’d let it slip by.

I tossed and turned late into our third night. Noah was sprawled out on his bed across from mine, the sheet over his body faintly wafting in a cool air-conditioned breeze, and a recurring question haunted me: Will he ever know what it’s like to unleash his imagination on a wave, to feel his body and mind break through what he believes are his limits and put it all together into his own masterpiece?

When the first puddles of light touched the ocean, I was doing some yoga outside our room. It was hard to make out the surf with the sky the same metallic color as the water, but instead of yesterday’s flaccid waves I discerned a cylindrical shape to them. Squinting at the sea, I saw another wave reach out from the one-dimensional monochrome and threaten to pitch, then melt away, before folding into a sharp hook. Definitely real.

I opened the door to our room. Noah slept with one arm hanging off the bed. Slipping right into my father’s shoes, I envisioned waking Noah up and hauling him out of bed and into the surf. You can’t let him miss another golden opportunity! The beautiful surf might only last an hour. It could be another year before he gets a chance like this.

Next year he’ll be 15, in full rebellion and most likely way out of reach. This is it! This is what you’ve been waiting for!

But when my arm reached out to shake Noah, it just hovered in the air.

Lost in some corner of my mind, half formed, there seemed to be another way to help my son.

Maybe I’d figure it out in the ocean, I told myself.

Leaving the door ajar, I paddled out.

“Why didn’t you wake me up?” Noah said when he finally made it into the lineup, the sea bulging with muscles of swell, the gray-green jungle amassed behind him.

“I wanted you to get your beauty sleep.”

He smirked and rolled his eyes. “It looks insane out here!”

“Beautiful shape,” I said, poker-faced.

“I’m going after the vertical snap today!” he said, spinning round and paddling into a little nugget.

The waves were so consistent that I did not see him for over an hour.

I’d just finished an incredible ride, slipping over the back of the wave, when Noah popped up, having duck-dived under the same wave.

“I suck,” he whined.

Face squeezed, he was crying, and it was in such sharp contrast to everything I was feeling and would have expected to see in my son that I chuckled.

“What’s wrong?” I said.

“I work on it and work on it, but I never get better. All my friends are better. I’m not good at anything.”

I wanted to scream. Scare away those demons. Squash them with my bare hands. I wanted to save him. How many times had I done that? Rescued him, salvaged the surf session or the ski run from a tantrum, prevented him from embarrassing himself at a birthday party? “Grab my leg and I’ll tow you back out,” I wanted to say, but I remained silent instead.

I got up around seven and Noah's bed was empty. I meandered to the common room and poured a cup of coffee. Where's Noah? I asked a friend. She pointed out the window: “He's been surfing since dawn.”

I stuttered there in dissolution, and in that void percolated an idea long hidden in the corner of my mind: my father never had to contend with me as a teenager, and seen from the other side of that equation, I never had to contend with him. That’s why I couldn’t get a feel for what Noah and I were going through, and that’s what held me back from taking action. The road we were on had stretched beyond the map my father left for me.

“Why do I keep blowing perfect fucking waves?” Noah cried out.

“Hey,” I said in a booming voice, snapping him from the downward spiral. “Who cares how you surf? That’s not the point anyway.”

“Then what’s the point?”

“This. Right now. The pursuit. That you have passion.”

“Fuck passion.”

“Ah, now take that and paddle for every damn wave and ride it like your life depended on it.”

“But it does.”

“Yep,” I said and paddled away.

For the rest of the morning, each time I crossed Noah’s path he was either momentarily elated from a turn or drop-in, was lingering by himself in despair, was beating a fist on the deck of his board, or was digging hard to catch yet another immaculate blade of water. I was surprised that he never asked me to comment on any of his maneuvers.

At one point, I went in to rehydrate and eat a banana. Walking back up the beach, I saw Noah turn off the bottom of a wave, go straight up, crack the lip, and snap the tail around but not his shoulders, causing his board to stick at the top of the wave. Then he air-dropped to the trough and blew apart. When he surfaced, he grabbed his board and flung it into the air, opening his mouth and howling, but the churning sea swallowed his cry. As his surf session progressed, every time Noah unraveled in anger or frustration, releasing a little tempest, it was absorbed in the fluidity and vastness of the ocean. Each new wave was a chance for him to start again—an idyllic space to work through his fury and hone his character—and was clearly beyond anything I could offer.

The surf tapered off around noon. Noah’s knees were shredded—chafed by his tail pad and cratered by the salt water—and it was hard for him to walk, much less surf. I knew he was in real pain because it even prevented him from playing volleyball in the pool. Every limp and grimace seemed to reiterate that he would probably not surf again before the trip was over. I wondered: Would he use his knees as an excuse for not getting back out there?

That evening our whole group was in high spirits, buying each other beers and toasting the waves. Yet Noah didn’t talk about his waves; he kicked back in one of the pigskin chairs, sort of lost in a daze, drifting on some private current. After dinner he ducked away with the girls he was hanging out with, and I crashed out before he got back.

Stiff and sore, I decided to sleep in. Near dawn a door creaked, and I heard some scuffling and figured Noah was going to the bathroom. When I got up around seven his bed was empty. I meandered to the common room and poured a cup of coffee, expecting to find him over a plate of huevos rancheros. The only person in the room was the aunt of one of the girls Noah had become friends with, and I asked her if he was in their room “horsing around.” She pointed out the window: “He’s been surfing since dawn.”

A small figure dropped in at the top of the point near the big rocks, and when the figure got to the bottom of the wave, the lip was standing well over him, his neon blond hair popping out against the blue wall. I rushed to our room and grabbed the camera.

Noah was back at the top of the point, and he took off on another overhead wave. Setting a high line to reach a quickly peeling section, he drafted off his speed at the bottom of the wave, let the lip build up, and then shot up the face and cranked the board around—cutting a deep groove in the face of the wave—repeating the maneuver several times all the way to the shore. When he trotted by me toward the point, I motioned to the camera. Without a word he walked over and stood beside me. I shaded the display window from the sun and scrolled through sequences of his turns.

“I’m not going as vertical as I thought,” he said.

“We never do,” I said. “We see the lip pitching above us, and our brains project us slightly forward of it, just ahead of the critical hook.”

“I have to fight through that.”

“Yeah, that’s what it comes down to.”

He nodded, and I noticed that his knees were wrapped in duct tape.

“Where’d you get the duct tape?”

“From one of the guys.”

“Good thinking.”

He did not respond. His gaze was following a wave, and I could see his eyes dropping to the trough and making an imaginary line right up under the throwing lip. His nostrils flared, and I got a sense of what had changed in him yesterday. That surf session had stripped him down to his core, and by the end of it there was nothing left to hide behind, his passion unchained.

Noah turned and jogged up the point, and I sat back on the rock.

After a few attempts, he started getting his board to go straight up the face, fighting off the instinct to project out, and he pulled off a series of legitimate vertical snaps. But what was more impressive was that he was taking off deep and choosing the right lines on the right waves, which allowed him to explore a wide assortment of maneuvers and really push what he thought were his limits. I knew from experience that the bedrock of faith he’d found today would never desert him.

“That was a masterful session,” I said when he came in for a break.

He nodded, a budding smile just beneath his mouth.

“Thanks, Dad. Thanks for taking me here and putting up with everything.”

“You’re welcome.”

The smile broke all the way free and he said, “I’m going back out.”

I watched him trot along the path, disappearing down the beach stairs, and I flashed on Grandpa showing me the lean-to for the burro. Of course he knew it belonged to someone else, and that there was a good chance the owner would find me, but instead of intervening he’d let me have my own experience.

Noah reappeared on the sand. He ambled to the shoreline and followed the curve of the cove all the way to the point.

Norman Ollestad is the author of the bestselling memoir . His new book, , is available through Amazon.