LAST FEBRUARY, A cheerful 25-year-old Brit named Ellen MacArthur sailed into incandescence aboard her Open 60 Kingfisher with an improbable second-place finish in the Vendée Globe, a 26,000 mile, nonstop, solo circumnavigation that is justifiably considered the world’s toughest yacht race. Why improbable? Because it was MacArthur’s first Vendée bid, and she had been racing solo for just four years. But mostly because MacArthur, who stands five-foot-two and weighs 130 pounds, is the youngest person ever to have attempted the race, much less finished it. Her time of 94 days, four hours was the second-fastest solo circuit in history, and the fastest ever by a woman. Even race-winner Michel Desjoyeaux, a 35-year-old French sailing star who found himself dueling with MacArthur for the lead two weeks from the finish, was stunned by her performance. “She’s a mystery to me,” Desjoyeaux said on the dock after the race. “I don’t know what I have been doing for the past ten years.”

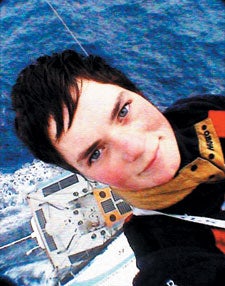

High-wire act: A video camera attached to the mast captured this image of MacArthur dangling above Kingfisher and the Southern Ocean during the 2000-2001 Vendé Globe.

High-wire act: A video camera attached to the mast captured this image of MacArthur dangling above Kingfisher and the Southern Ocean during the 2000-2001 Vendé Globe.

It’s a long way from a landlocked home in the hills of Derbyshire to the Vendée Globe. MacArthur got hooked on the life afloat at age four, sailing off England’s east coast with her aunt during summer vacations. By 22, she had knocked off two major transatlantic races, the 1997 Mini-Transat and the 1998 Route du Rhum, and was launching her campaign to sail around the world, mastering everything from diesel mechanics to weather forecasting to one-on-one racing tactics. More than anything else, the Vendée is a merciless test of character, and MacArthur unveiled an indomitable spirit. She laboriously hand-sewed a shredded spinnaker, made four exhausting climbs up her 79-foot mast to repair broken gear, destroyed one of her two daggerboards on a submerged object, and within days of the finish was in danger of losing her mast.

The grit and soul of MacArthur’s Vendée effort boosted her into the sailing stratosphere. Her Web site survived nearly 500 million hits over the course of the race. Hyperbolic sailing commentators hailed her as the greatest sailor England has ever produced. Slavering European advertisers begged–in vain–for her endorsement of everything from hair spray to vacuum cleaners. (Durex, a condom company, hoped to get her to pose in a rubber dinghy.) Even the queen took note, dubbing MacArthur a member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

MacArthur is now invading the elite multihull racing world. On November 4, she and 1993 Vendée Globe winner Alain Gautier will double-hand a 60-foot trimaran from France to Brazil in the high-speed Transat Jacques Vabre. For next year MacArthur is considering another solo lap of the planet, in the 2002 Around Alone race (which, unlike the Vendée, has stops). ���ϳԹ��� managed to catch the peripatetic sailing prodigy shortly after she and four mates had steered Kingfisher to a win in the Portsmouth-Baltimore leg of the EDS Atlantic Challenge. MacArthur was rushing to catch a plane back to Europe to go, you guessed it, sailing.

���ϳԹ���: What makes you a good sailor?

MacArthur: You’ve got to have common sense. And you’ve got to be able to cope with things going wrong. It’s not going to be a drama. If the batten breaks, you have to go and fix it. So many people get so strung-up about things.

O: When you were in your teens you were thinking about going into veterinary medicine but dropped it to sail. Why the radical career change?

MacArthur: I got glandular fever, and I was flat for a month. During that time the [1993-1994] Whitbread Round the World Race was on TV. All of a sudden I just decided, That’s it, I’m not going to go to university, I’m going to sail. Life is too short to go off and do something you are not 100 percent sure you want to do.

O: Was your ambition always to go into the top levels of racing?

MacArthur: I just wanted to be on the water. I knew that one day I wanted to sail around the world. I had saved all my dinner money for years and years at school for a boat, and I managed to buy a little 21-footer named Iduna when I was 17. She was absolutely knackered. Everything was broken. I refitted her during five months and then sailed her single-handed around Britain.

O: Why were you so drawn to single-handed racing?

MacArthur: When I bought Iduna I automatically took out one of the berths. I don’t know why I did that. I didn’t mentally think, I’m never going to sail this boat with someone else. I took out that berth because I needed more space.

O: There aren’t a lot of top single-handers with XX chromosomes. How have the other sailors received you?

MacArthur: The Italians nicknamed me Piccola Roccia, their “Little Rock.” So many people say, “How’s it feel to be a young girl in this sport?” and “How’s it feel to be the only girl in the race?” I never considered myself any different from them. Never. It wasn’t an issue. I’m just Ellen doing what I would be doing if I were Robert.

O: Did it intimidate you that during the 1996-1997 Vendée Globe one sailor died and three had to be rescued?

MacArthur: “Intimidate” is not the right word. It made me more aware. It makes you realize that you can never beat the ocean. You don’t go out there to do battle with the ocean. You go out there to sail with it and survive on it.

O: What’s the most dangerous moment you’ve ever had on a boat?

MacArthur: During the Vendée, near the doldrums. I was up the mast trying to fix the wind instruments, which had failed for a second time. The boat was on autopilot, steering by compass, when the wind suddenly changed directions in a squall. The boat started to jibe back and forth with me pinned way up the masthead. I got bruised and battered up there. I didn’t have time to be scared, but it certainly made me shake when I finally got down to the deck.

O: What was the toughest part of the Vendée globe?

MacArthur: The hardest moment for me was getting off the boat at the finish line. I looked after Kingfisher all that time. Every time something broke or went wrong, I would be there. That I was standing there on the finish line was living evidence she did a damn good job looking after me too.

O: During the race, you took 891 naps, and never slept more than three hours at a stretch. Did you ever get so tired that you simply couldn’t function?

MacArthur: Toward the end I was very fatigued, and this took its toll. But for most of the race it’s OK to sleep like this, mostly in 20-minute snatches. When you have problems, you find big reserves. It’s afterward you realize how exhausted you are.

O: You ran into a whale in a transatlantic race. In the Vendée, you woke up to find Kingfisher barely clearing an iceberg, and then hit a submerged object, which tore off one of your daggerboards. Don’t you get nightmares?

MacArthur: When I first hit what I now think was a container, the noise was gut-wrenching. I thought the bottom of the boat was gone. But if you worry about these things all the time, you’ll never get round.

O: You sound pretty unflappable. Do you consider yourself a tough person?

MacArthur: I’m quite tough. But I can also be quite sensitive. You can be sensitive in some areas and tough in others. I’m not somebody who gives up.

O: The Southern Ocean has taken on a mythic aura. Sailors get thrilled, and killed, there. What was it like for you?

MacArthur: It’s so pure and clean and wild. Going to the Southern Ocean is like standing in the middle of a desert. You are thousands of miles from anywhere, and you feel very priveleged to be there. It’s a big thing just to get there.

O: It must get pretty lonely, with only the albatross for company. Did you talk to them

MacArthur: Anyone would do that down there. Anyone.

O: Sailors are notoriously superstitious. Some whistle for wind, and then there are rabbits, any mention of which is thought to bring on big storms. Are you superstitious?

MacArthur: I would never use the word about the animal with the long ears on board. In fact, if I ever saw it in a book, or anyone said it during a race, I would have to go straight to the mast and scratch it.

O: There is an all-woman team racing around the world in this year’s Volvo Ocean Race. Is that something that interests you as a way to draw women into the sport?

MacArthur: It’s amazing to be able to inspire people. I love that. But I wouldn’t have a women’s team; I would have a team. The world’s made up of 50 percent women and 50 percent blokes. I’m not out there wave a women’s flag. I’m not saying, “Women can go and do this.” If you really want to do it you can go and do it. It doesn’t matter what sex you are.

O: You did a great job e-mailing from the boat. Did you find the ability to be in constant contact with the world a burden?

MacArthur: It has always been a big objective for our project to use technology to share this story with as many people as we could. I also felt that communicating let some of the stress out, even if I was pouring out my soul in front of millions of people. One day maybe I’ll set off alone with no communications just to sail around.

O: How does it feel to be famous, to be known by your first name, like Madonna?

MacArthur: Being in the Channel and seeing 250,000 people screaming your name at the finish line is pretty amazing. I was standing on the foredeck waving to these people, feeling like Ellen was standing behind me. You think, What have I done to deserve this?

O: Are you keen to go back and win the Vendée globe?

MacArthur: Yeah. But it’s not time yet to make that decision. It’s a big thing to do the Vendé, and the past few years have been completely crazy.

O: Do you ever get any time to yourself these days?

MacArthur: Not since the Vendé. To finish that race, everything has to go into it. Everything. You draw all your resources, and when you cross that finish line it’s like someone pulls the plug out. The release and relief is massive. Because it’s over. It’s all over. But actually, it’s just the start.