MARCELO CABRERA, MY GUIDE, couldn’t understand why I would come all the way to the Iberá wetlands, a remote subtropical region of northern Argentina, just to catch a piranha. Instead of chasing nasty little fish known for devouring livestock, visitors to Iberá usually want to explore the 5,000-square-mile complex of swamps (roughly the size of Connecticut) that brings to mind the Florida Everglades of a couple centuries ago; they want to fly-fish for dorado, a large, golden-colored, aristocratic fish known locally as the river tiger; they want to feel the bizarre sensation of walking on the so-called floating land; and they want to experience the stunning variety of wildlife, including caimans, marsh deer, wolves, freshwater rays, huge snakes, monkeys and big cats, 350 species of birds, and more types of fish than you could order in a Tokyo sushi joint. I promised Marcelo that I would like to do all that stuff, too, but I only had a couple of days—hardly enough time to experience the full glory of this wilderness. It seemed to me that since piranhas would reportedly eat anything living in the wetlands, they were the distilled essence of the place. This reasoning probably came across as a little shaky to Marcelo, but as we stood in the skiff and sized each other up—two skinny guys in cutoff shorts—I felt as though we reached a compromise of sorts. Marcelo made a vague gesture with his hand, suggesting that we might look for a piranha sometime later in the day.

argentina, ibera swamps, piranhas, dorado

argentina, ibera swamps, piranhas, dorado

argentina, ibera swamps, piranhas, dorado

The brevity of my stay was the fault of a common misconception about Argentina: Like most people, when I thought of Argentina, I thought of the Andes and the arid grasslands of the south. So I spent a couple of weeks down in Patagonia, fishing for brown trout in a mountainous region of streams and ski lodges similar to those near my home in Montana. I worried that I’d developed a personality disorder that inspires a person to travel extremely long distances to do the same things he does at home.

My friend Jay Nichols, an old roommate with whom I was traveling, felt the same way. Fortunately, we ran into an Argentinian named Martin Kambourian, who was collecting trout-fishing footage for his TV show, produced in Buenos Aires. Martin spent a day lazily recording Jay and me toying with the local trout, which he viewed with all the excitement of netting sardines, all the while telling tales of adventure about the Iberá wetlands. He talked about giant dorado and snapping caimans and frogs the size of our heads. He was insulted that we’d come to Argentina and weren’t planning to go there. He offered to make some calls.

The next thing I knew we were flying north to Buenos Aires, where we would board a bus for a nine-hour trip farther north. A guy from Estancia El Dorado, Carlos Sanchez, would pick us up in the town of Mercedes, one of the gateways to the Iberá wetlands.

Mercedes is a dingy town of squat concrete buildings and lush courtyards. Carlos was waiting there, as promised. He looked to be in his mid-thirties, and his clean white shirt contrasted with the muddy pickup into which he tossed our bags. “My first business is selling cows,” he said, which I took as a sort of introduction. “My second business is catching the dorado on the fly.” It was then that I realized we weren’t heading to some posh dude ranch decorated to look like a cattle operation.

When Carlos told us that his estancia was in Mercedes, he was speaking in a roundabout way. We drove more than an hour on a dirt road covered in knee-deep water for miles at a time. The Sanchez family has been raising cattle on the Iberá wetlands since 1923, and Estancia El Dorado is one of two ranch outposts they maintain in the backcountry. The estancia is a collection of small white buildings on the edge of a forest. The ranch’s gauchos, South America’s badass breed of cowboys, live in neatly organized shacks next to the main house, which includes the guest quarters. When we drove up, a freshly slaughtered lamb hung from a post outside, and a knife was stuck into a nearby stump. A large lagoon stretched away from the front yard. The Corrientes River, which forms the backbone of the wetlands, flowed in the distance. I could see the wakes of fish swimming in the lagoon, and some children were chasing them with child-size harpoons. Jay and I threw our bags into a small, clean room with two single beds, then ate a lunch of lamb prepared by the estancia’s chef. Moments later I was standing in the bow of a 15-foot skiff explaining to Marcelo that, yes, I would like to catch a piranha.

Jay and Carlos motored downstream in another skiff as Marcelo and I motored up. I could see great distances from the boat, because the banks of the river were barely high enough to contain the water. The boat’s wake rolled over the riverbanks like a spilled drink. We passed birds perched on pieces of free-floating land, which illustrate one of the defining features of Iberá: Much of the “land” in and around the wetlands isn’t land at all.

Huge, intertwined mats of floating water hyacinths capture organic particles deposited by the wind and water, forming soils that permit the growth of plants and trees. These have evolved into floating coasts, called hydrophytic forests. Currents can break the forests apart and set smaller pieces adrift. The tenuous nature of the land itself helped protect the heart of the wetlands from European settlement for hundreds of years, and in 1983 legal protection was given with the formation of the Iberá Reserve by the government of the province of Corrientes. A handful of lodges offer guided boat tours, horseback riding, and birdwatching and fishing trips, but Iberá remains a paradise for swamp rats who like their wetlands wild.

Marcelo killed the engine next to a deep pool, and I began casting out a fly that looked like a wet hamster. On about my tenth cast, I felt a powerful jolt. A dorado kicked up a large swirl of water, then launched its torpedo-shaped body completely out of the water in a blur of gold, red, and black. It shook its head about six times and landed backside-down. To make sure its teeth didn’t ribbon my fingers, Marcelo popped it free with needle-nosed pliers when I got it to the boat. (Dorado are catch-and-release in the Iberá wetlands.) The fish weighed about eight pounds, but its compatriots in these parts can hit up to 22 pounds. After I caught four more, my forearm was played out.

“Now,” Marcelo said, “other fish.” We quickly caught a few tarihira, which look and fight like souped-up walleyes. We also caught some boga, a shadlike fish that Marcelo tossed into the cooler for dinner. He seemed to have forgotten about piranha, so I started whining again. “If I don’t get a piranha now,” I explained, “it will never happen.” Jay and I would share a boat the next day, and I figured he would have his own ideas about what we should do. (Actually, day two would involve dorado, piranha, biting ants, a sunburn, vanishing frogs, and a delicious piranha dinner, but how could I know?)

Marcelo motored upstream and then stopped near an ankle-deep marsh. Hundreds of sabalo, which look like carp, were cruising for food in the shallow water, their dorsal and tail fins sticking out above the surface. A flock of herons came flying over, so low their long white wings rippled the water. The sabalo herded ahead of the birds in a great arc, like crumbs being blown off a table. As the fish poured back into the river, something attacked them from beneath in an eruption of splashing water. Wakes sped away, and bits of weeds floated up to the surface amid swirls of muck. I pasted out a cast.

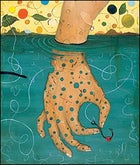

Things then happened in a confused way. I was hooked onto something like an electric paint mixer, which turned out to be a two-pound piranha. The fish was having trouble on both ends: I was reeling it in, and a gang of other piranhas was attacking it from behind. I yanked it into the boat and then noticed blood on my foot. I wiped the top of my foot clean but couldn’t find the cut. I checked the bottom. Nothing. Then I looked at the piranha and realized where all the blood was coming from: Its rear half had been eaten off. Marcelo gave me a look that said, Well, there you have it. Then he cranked the boat back to life and began puttering down the winding river path that would lead us home.

ACCESS + RESOURCES

The best times to visit the Iberá wetlands are March to May and September to November (the fishing peaks in December, which is also the hottest month). Buses leave for Mercedes several times a day from Buenos Aires; the capital’s massive bus terminal, Terminal de Omnibus de Buenos Aires (011-54-1143-100707), is at the corner of Antártida Argentina and Calle 10 in the Retiro barrio, about 25 miles northeast of the international airport. The nine-hour bus ride costs between $46 and $54. An alternative is to catch a domestic flight on Aerolineas Argentinas ($212 round-trip; 800-333-0276, ) from Buenos Aires to the city of Corrientes, capital of the province of the same name. Flights leave from Jorge Newbery Airport, which is a couple miles northeast of downtown Buenos Aires, in the Palermo district. From Corrientes, it’s a three-hour bus ride to Mercedes. Estancia El Dorado reservations and pickup arrangements must be made in advance with Carlos Sanchez (011-54-3773-420660, eldorado@ibera.net). Rates are $250 per day, including lodging, excellent family-style meals, a guide, a boat, and transportation. Book a seven-day trip, including international airfare, for $2,995 (double occupancy) through the U.S.-based Center for Argentina Tourism (800-216-0049, ).