Surfing

The Upgrade

Call it plan B. Free-soloingÔÇöno ropes allowedÔÇöclimbers Dean Potter and Leo Houlding will soon be wearing lightweight versions of BASE-jumping parachutes to combat the discipline’s primary, um, downfall: You slip, you die. Many think that a chute might turn certain death into a coin flip.

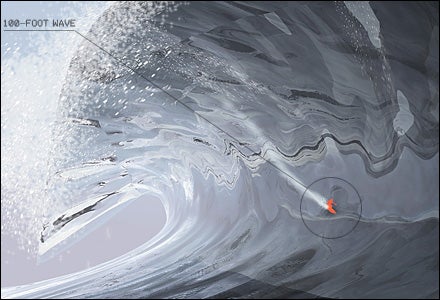

THE QUEST TO CATCH A 100-FOOT WAVE

RIDING A TEN-STORY wave is a colossal physical feat. But the truth is, the primary challenge isn’t the surfing; it’s the finding. Few folks have ever witnessed a wave that size, let alone one with a face that could be surfed. To date, the biggest wave ridden (and photographed) was a 70-footer at Maui’s Jaws that Pete Cabrinha towed into behind a jet ski in 2004. The Billabong Odyssey, a much-hyped three-year, $1.5 million mission to seek out and surf the world’s biggest waves, which ended in 2004, turned up several new breaks but nothing that approached the century mark.

And yet surfersÔÇöand a few surf forecastersÔÇöremain convinced that the right wave will appear eventually. Among the two dozen pros ready to board a plane at the first sign of a monster swell are California’s hard-charging Long brothersÔÇöGreg, 24, and Rusty, 26ÔÇöand Hawaiians Garrett McNamara, 40, Shane Dorian, 35, and, of course, 43-year-old Laird Hamilton. But this race could well be won by a dark horse: Australia’s Ross Clarke-Jones. The burly 41-year-old has both the fierce dedication and serious sponsor dollars that are essential to big-wave hunting. Last year, Clarke-Jones’s Red Bull team pioneered two new breaks off Japan, dropping in on typhoon-fueled waves. His latest strategy, however, is to ignore storm systems and seek out Poseidon-style rogue waves. “There are hundreds of them every year,” he says. Clarke-Jones is currently working on getting access to satellite data that will help him pinpoint rogue waves as tall as 120 feet in the Bass Strait, between Australia and Tasmania, right outside his home in Torquay, Victoria.

And if he does locate one? “It’ll be like trying to ride a dinosaur. We’re not going to be smiling and waving to the cameras,” says Clarke-Jones. “We’re just hoping to hang on.”

Rock Climbing

UP EL CAP WITHOUT A ROPE, AND REACHING FOR 5.16

THE NOTION of free-soloing (climbing without ropes or safety equipment) the 2,900-foot granite face of Yosemite’s El Capitan borders on insane. And yet there’s a growing sentiment in the climbing community that some steel-nerved maniac will attempt it in the next year. Who? Tommy Caldwell, 29, the only person to have free-climbed (no mechanical aids but ropes to catch falls) two El Cap routes in one day, may be best suited to the task, but he says he’d never take such a risk. The most likely candidate is 24-year-old Austrian Hansj├Ârg Auer, who in April free-soloed a 5.12c line on Italy’s 2,789-foot Marmolada. Other talented climbers with the gall to make a bid, including Dean Potter and Alex Huber, are familiar with the moves on the 5.12d Freerider, the easiest line up El Cap. “A lot of people are working on it,” says Caldwell. “It’s just a matter of time before one of them gets good enoughÔÇöor just confident enough.”

On the sport-climbing front, there was a time not long ago when the 5.15 gradeÔÇöthink blank limestone, slightly overhungÔÇöwas considered impossible. But now that Chris Sharma’s latest project weighs in at 5.15c, it’s likely that 5.16 is just around the corner. And Sharma, 26, isn’t the only one with the potential to break the barrier. A standout among upstarts: 14-year-old Slovak Adam Ondra, who recently notched 5.14dÔÇöfour letter grades harder than Sharma had reached at that age. “Glue a quarter to the wall and these guys will grip it,” says Yosemite speed climber Hans Florine.

The Upgrade

The propulsion mechanism on Ted Ciamillo’s new pedal-powered wet sub (scuba gear required) allows him to hit 4.5 knots by mimicking the kick of a dolphin’s tail. This spring, Ciamillo plans to power the contraption 2,300 miles from West Africa to the Caribbean in only 40 days. At night, he’ll raise sails for an added boost.kayaking

Alpinism

IT’S NOT ABOUT THE ALTITUDE

ELITE ALPINISTS have long since stopped thinking of Everest as, well, the Everest of mountains. The focus today is on harder routes, not higher peaks. In that spirit, 28-year-old Josh Wharton went to the Karakoram in August with Wyoming-based Exum guide Bean Bowers to attempt the unclimbed 8,038-vertical-foot north ridge of Pakistan’s Latok I. The ice-and-rock line, having rejected more than a dozen teams of top climbers over the past 30 years, is considered one of alpinism’s greatest remaining prizes. “It’s been my dream since I was a kid,” says Wharton, who in 2004, along with fellow Coloradan Kelly Cordes, established the world’s longest rock route, the 7,400-foot southwest ridge of Pakistan’s Great Trango Tower.

Colin Haley, 23, still an undergrad at the University of Washington, just completed one of the most productive years ever for an American climber: In July 2006, he ticked off the 6,500-foot north face of Alaska’s Mount Moffit, flew to Patagonia six months later to link up the west and south faces of Argentina’s famously foul-weathered Cerro Torre, then in March returned to Alaska, where he notched the first winter ascent of Mount Huntington, a first ascent on Mount Robson, and a route up Mount McKinley’s Denali Diamond, all in four months. “Colin is poised to change the landscape of alpinism,” says fast-and-light-mountaineering pioneer Mark Twight. “But like all ambitious young guns, he must first survive his initial trajectory.”

Meanwhile, 37-year-old Steve House, of Bend, Oregon, one of Haley’s mentors and still America’s top alpinist, just flew back to Pakistan to attempt K6, which was last climbed in the 1970s.

And all of the world’s alpinists are suddenly eyeing the Siachen region, on the IndiaÔÇô Pakistan border, where a decades-old conflict has kept climbers from attempting 17 of the world’s unclimbed 7,000-meter peaks. After four years under a steady cease-fire, the Indian Mountaineering Foundation has begun easing permit restrictions.

Kayaking

FINISHING THE TSANGPO, AND FOLLOWING THE CONGO FROM SOURCE TO SEA

IN 2002, WHEN Scott Lindgren and his six-man crew became the first to paddle Tibet’s Upper Tsangpo River, at the bottom of one of the planet’s deepest canyons, they took out at the start of a roughly 75-mile gorge leading to the Indian border. That section, the Lower Tsangpo, is one of whitewater’s longest, most challenging sets of unrun rapids. “There was no way to move around in there. It was just too steep,” says Lindgren. “It could be years before it gets runÔÇöespecially if the Chinese dam it.”

Or not. “I think it’s inevitable, if not this year, then certainly within the next five, that it will be paddled,” says Ben Stookesberry, 29, a veteran of more than a dozen international first-descent expeditions and the most likely man to try. To prepare, Stookesberry is planning the first descent of the Subansiri this fall. The river shares the Tsangpo’s geographyÔÇöfalling off the Tibetan Plateau toward India at a gradient of 150 feet per mileÔÇöbut has roughly half the volume. “I’d like to think it’ll be a warm-up,” he says.

The Congo River, kayaking’s other big adventure prize, provides a different set of obstacles. “Combine the hardest whitewater and the most threatening wildlife with the instability of the African continent,” says Colorado-based Brad Ludden, who ran the upper section of the Congo in 2000, at 19. “The only guy I knew who was even considering a source-to-sea mission expected to lose at least one paddler.” One reason nobody is currently planning a descent.