Twelve inches.

Mike Parsons’ 77-foot wave from January 6, 2008

Mike Parsons’ 77-foot wave from January 6, 2008

Mike Parsons’ 77-foot wave from January 6, 2008Garrett McNamara on the biggest wave ever surfed?

Garrett McNamara on the biggest wave ever surfed?

Garrett McNamara on the biggest wave ever surfed?After six months of waiting, that’s the difference in height determined to exist between a ridden by Mike Parsons on January 6, 2008, atop the Cortes Bank and a 78-foot behemoth tackled by Garrett McNamara on November 1, 2011, at Praia do Norte, Portugal. The verdict was rendered last Friday at the Billabong XXL Global Big Wave Awards by a panel of nine expert surf judges after a spirited and occasionally heated debate. This 12th annual bacchanalian bro-fest went down at Anaheim’s Grove theater before a packed house of the bold, the beautiful, and the drunk. Perhaps Foo Fighter and award presenter Dave Grohl put it best when he said, “I’ve been playing rock music for 25 years and I’ve seen some people do some stupid shit. But you guys are the craziest motherfuckers I’ve ever seen.” Indeed, true to enduring form, this Oscars of surfing did not fail to blow minds, deliver lucrative rewards and spawn a little controversy.

It’s fairly hard for me to believe, buf I’ve been to 10 of the 12 XXL’s ever staged—the first way back in 1998. Then, as online editor for , I watched a former magazine editor named Bill Sharp present the K2 Big Wave Challenge—the XXL’s precursor. Sharp’s concept was fiendishly simple. Measure the biggest waves of the year, and reward the surfer who rides the very biggest with a payout equal to $1,000 for every foot of wave height.

A few surfers like Hawaii’s Ken Bradshaw thought the idea a crass and exploitative way to get someone killed, but the K2BWC brought needed focus and huge media attention to big-wave surfing.

The award went to , who paddled into a 52-foot world record at Todos Santos, Mexico—a wave judged to have finally eclipsed the mythic, unphotographed 50-footer of Greg ‘da Bull’ Noll at Makaha, Hawaii, in 1969. Interestingly, the K2 was only open to paddle-surfing entries as jet-ski assisted tow-surfing at spots like Maui’s Jaws and Oahu’s Outer Log Cabins was just beginning to blow up. Had towsurfing been considered, a grainy video still of a long-reputed 80-footer by Bradshaw at Outer Logs might yet represent a still-standing world record.

The K2 idea was reborn as the Surfline/Swell Big Wave Awards in 2001—just as the surfing world was having its collective mind blown by Jaws, Mavericks and a newly revealed California seamount called the . A hot date who is today my wife joined me to watch a seasoned charger from San Clemente named Mike Parsons narrowly edge out Maverick’s icon Peter Mel and Laird Hamilton (in Hamilton’s first and only XXL appearance) to secure his first of two world records—on a flawless 66-footer at the Cortes Bank.

Though Hamilton would bow out to do his own thing, the XXL’s evolved into surfing’s marquee event. New world records bounced back and forth between Jaws, Mavericks and Cortes. Mindbending new waves were revealed off Spain, France, Western Australia, Ireland, Tasmania and Tahiti. Some of them, particularly the cyclonic Tahitian vortex at Teahupoo didn’t go so much up as out—and new XXL categories were added to accommodate: Monster Tube, Worst Wipeout and Performer of the Year.

The XXL’s reignited the careers of former small-wave pros lke Parsons and cast a spotlight on the exploits of surfers like Maya Gabeira, Carlos Burle, Grant “Twiggy” Baker, Darryl “Flea” Virostko, siblings Greg and Rusty Long, and seemingly indestructible Hawaiians like Shane Dorian, Ian Walsh, Mark Healey and Garrett McNamara. “GMac” became famous for a stunning 2002 Monster Tube at Jaws, horrific Teahupoo floggings and a successful 2007 excursion to towsurf a “seiche” wave produced by the calving ice slabs from Alaska’s Child’s Glacier. The last couple of years also saw the return to form of a quiet, cerebral charger from Capistrano Beach named Nathan Fletcher.

Fletcher, 38, is the spawn of California surf royalty. His late, great uncle Flippy was one of the first to graft a fin to the back of a big wave board and challenge the behemoths at Oahu’s Makaha and Kaena Point. His aunt, Joyce Hoffman, is a former women’s world champ; his father, Herbie, a pioneering jetski explorer of outer Hawaiian reefs; and his brother, Christian, is surfing’s first true aerial artist.

Nathan’s own date with destiny took shape in August, when the late, great forecaster Sean Collins announced a storm akin to the red spot on Jupiter tearing through the roaring forties. A cast of the world’s best made a mad scramble to reach Tahiti, but many were already there, competing in the Association of Surfing Professionals Billabong Fiji Pro. The earth-shaking waves on August 27 kept most pros out of the water and left even Tahitian veterans slackjawed. Arriving late and disheveled, Fletcher was picked up by former XXL champ Makua Rothman. When a mutant slab sucked the ocean off the reef Rothman slung Fletcher into a clenching maw that seemed impossibly deep to escape. The heaviest wave ever attempted.

“I was totally unprepared.” Fletcher said. “At that point, I was thinking I just gotta make it to the shoulder—I can’t survive if I don’t make it to the shoulder. Come to the bottom and realized that I wasn’t making it. I made most of the wave, but started falling back—not thinking humans can survive it. To myself I was just like, okay, it’s been great. Life’s great. This is it.”

Fletcher was flicked arms akimbo into the air, deep in the the barrel, leaving behind an iconic still image before he was obliterated. “It just got really violent,” he said. “I got smashed back, forth, up, down, and I don’t know how long it was, but all of the sudden, just as violent, I came to the surface. I couldn’t believe I was still alive. Couldn’t believe I didn’t hit the reef. Disbelief about the whole thing.”

The 43-year-old McNamara’s odyssey began in late 2011, after officials in the Portuguese fishing village of NazarĂ© invited him to explore the local waves and maybe make a documentary film. Sean Collins had told McNamara and several other surfers that a deep submarine canyon off NazarĂ© had the potential to focus swells into some of the biggest waves in the ocean. Yet when tremendous energy swept that canyon on November 1, McNamara was joined only by Andrew “Cotty” Cotton and Alastair Mennie, a duo known for XXL exploits at Mullaghmore Head, Ireland’s version of Teahupoo. The crew took turns arcing across cold, green 50- to 60-footers. But when a trio of truly giant lefthanders marched in, Cotton hucked McNamara onto a great, lumbering hillock. McNamara skipped down the line at breathtaking speed, trying to outrun the wave’s chandeliering lip. “It kind of crumbled and landed on me—just landed right on my shoulder,” he said. “It felt like a ton of bricks.”

The spectacular footage went viral. The promoters of Garrett’s project, a Portuguese cable and wireless company called Zon, asserted that the wave was 90 feet high, and a new world record. This, despite the fact that the actual arbiters of Guinness World Records—the XXL judging panel—was still months away from issuing a verdict. A number of big wave surfers cried foul, giving Sharp’s XXL’s, and Garrett’s accomplishment even more publicity.

It was against this backdrop that nine judges gathered to consider not only on Garrett’s wave, but a Jaws Monster Paddle effort by Hawaiian lifeguard Dave Wassel that might top a 57-foot record of Shane Dorian. Knowing the stakes, Bill Sharp says particular efforts were made to have this year’s images not only enhanced photographically but to employ video captures—particularly of McNamara’s wave, which was partially obscured by spray.

A surfer’s height would be measured to the inch, and the common practice of simply walking a pair of calipers up a photo was augmented by stacking precisely pixelated images of the surfer on top of himself via photoshop. A recommendation by surfer Ken “Skindog” Collins that a multiplier considering the length of a surfer’s shinbone—rather than just his total apparent height, which can be distorted by camera angles—was even utilized. Eventually, a unanimous consensus was reached: McNamara’s wave was 78 feet. Wassel’s was 52.

According to two judges, Maverick’s surfer and Surfing magazine editor Taylor Paul and the legendary Mickey Munoz, the scene was “tense.” Initial estimates of the height of McNamara’s wave in particular varied wildly, from 65 to 90 feet. “The judging—it’s not scientific,” Paul said. “It’s a bunch of surfing experts trying to do a job they’re not experts at. I think moving forward, it should be the surfers who help determine where the bottom [the flat trough of the wave where a measurement should start] is, and then you have professional forensic guys take up the rest.”

“Maybe you could write a program, a mathematical formula to figure out camera angles and whether they’re significant or not,” added Munoz. “Or is it just better to have a bunch of surfers in there? Everybody put a mark on where they thought the bottom of the wave was, and the marks were close. But a quarter inch difference—when you’re looking at a poster-sized photo—that becomes a significant difference when you walk it up a 50, 100-foot wave. My thinking is that the judging of this, it’s so subjective that I would have been more comfortable with a tie.”

But that’s not how it went down.

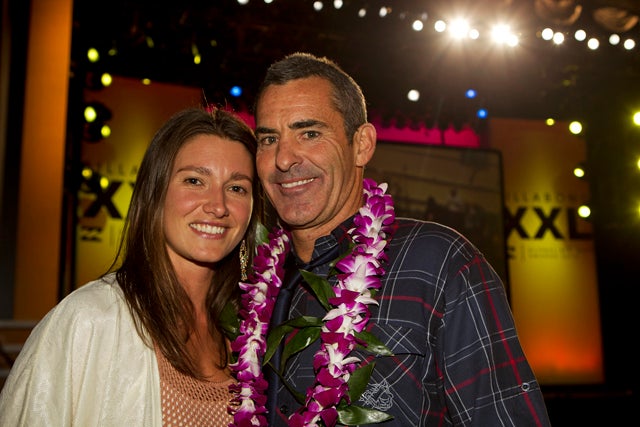

The pioneering McNamara was given a terrific wedding present by none other than Greg Noll and a pair of Playboy Bunnies: a world record he has been earnestly hunting for better than a decade and a nice haul of $15,000. When McNamara took the stage, Mike Parsons’ wife, Tara, told her husband, “you are not allowed to break that record.”

McNamara furthered his maniacal reputation with the Verizon Wipeout of the Year for an ass-backwards plummet off a WaveJet surfboard from the top of a Jaws peak that might have earned him another world record had he pulled it off.

Fletcher would net a record three categories: Monster Tube ($5,000), Surfline Performer of the Year ($5,000), and the . There was some confusion over the eligibility of his Teahupoo wave because it ended with a wipeout. But XXL rules state that a RotY contender must complete “the meaningful portion of the wave,” and when Sharp put out the ballot to a jury of 400 surfers that included XXL nominees, the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of allowing Fletcher’s ride. In the end, Fletcher defeated an astonishing Fijian paddle barrel by Aussie Ryan Hipwood by a mere three votes.

When he took the stage before the screaming horde, Fletcher thanked Makua Rothman, his family and his late friends, Andy Irons and Sion Milosky, for their inspiration. “I can’t even hold back the tears,” he said. “I’m so lucky.”

The point was echoed by McNamara. “We’re so fortunate,” he said. “We get to do what we love. We get to wake up every morning and think about where we’re going to go surf. It’s a dream come true. Every day I’m so grateful that I get to do this for a living. It is a dream. We are living the dream.”

Can I get an Amen?