It was just last month��when��Brock Little ��that he’d been diagnosed with liver cancer, and not long after when that the first round of chemo didn’t work and he wasn’t going to put himself though another round. That meant the 48-year-old��big-wave surfer��had weeks left, not years. The speed of the whole thing��was shocking. What wasn’t shocking to anybody who knew Brock was how he handled himself during this time.

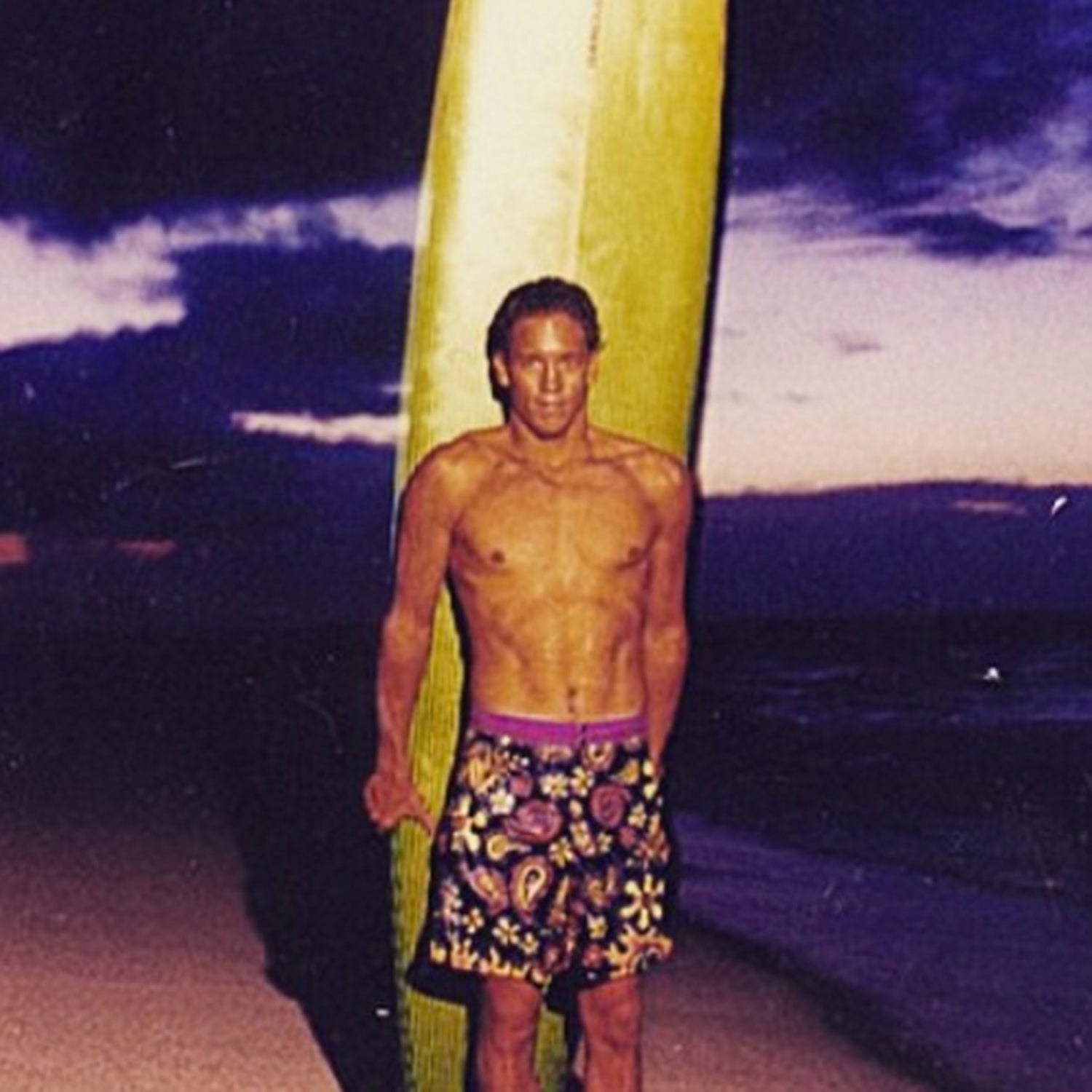

Brock grew up the son of two teachers in Honolulu, and went at life with humor. He always used humor. I met Brock in 1985, when he was 18 years old, beardless, and the new hot young gun at Waimea Bay. He started surfing at age seven at Waikiki. At Waimea, Brock was charging the world’s biggest waves elbow to elbow with bunch of crinkly-eyed salts who’d been at it for more years than he’d been alive. They took themselves seriously, the old Waimea crew—thought of themselves as fighter pilots, gladiators, polar explorers, take your pick. Brock thought that was hilarious.

“You know why I surf big waves?” he told me years later. “The big secret? Because it’s fuckin’ fun! It’s the funnest thing ever!”

“People ask me what I do for a living, and I do nothing. I pick up a check in the mail and go surfing.”

People loved this about Brock—that he laughed at��the sport, danced all over surfing’s spiritual manifest, and egotistical��pieties. It was never meant to be cruel—more like making fun of your best friends. As fond as he was for calling out surf industry bullshit, he was even fonder of being part of it all.

Better still, Brock’s favorite thing to laugh at was himself. By 1990, he’d laid��the cornerstone of his career at Waimea. Of��particular note was his performance at the Quiksilver in Memory of Eddie Aikau big-wave contest at Waimea that year, where he attempted to ride what a lot of people at the time were calling the biggest wave ever caught. He cartwheeled halfway down the face, came up, sputtered a bit, and paddled out to try again.

That same year, I interviewed��Brock for a . At that point, he was pulling down a low-six-figure income from sponsors. Did he ever wonder,��I��asked, about how strange his career looked to outsiders? “Oh yeah. It’s comedy, what I do,” Brock replied. “People ask me what I do for a living, and I do nothing. I pick up a check in the mail and go surfing. And whey the waves aren’t good in Hawaii, somebody pays me to surf somewhere else.”

Brock, in his younger days, was a semi-regular street fighter, and drove insanely fast, and would jump off pretty much anything—bridges, cliffs, what have you. He had two or three close calls in big surf. And, for a while after his��divorce several years ago, he drank too much. So when he told me, not long after making the cancer announcement, that he should have died ten or 12 times already, and that he was glad to have made it this far, it was just another instance of him laying down the no-bullshit card.

Brock would have loved more time. He was adamant that, despite all the radical situations he put himself into, he did not have a death wish. He’d also, of late, leveled out, slowed down, quit drinking, and backed off of huge waves. He was focused on stunt coordinating for Hollywood films (he’d done work for the films Ocean’s 11 and Pearl Harbor, and the TV show “Baywatch”). Given a choice, he’d have laughed his way through another five decades. But he wasn’t given a choice, and he accepted that with astonishing grace.

Last Friday Brock and some friends watched the live feed for the Titans of Mavericks surf contest. Santa Cruz, California, surfer Nic Lamb won, and mentioned Brock during his post-final interview. Not long after that, Brock dropped a comment on one of Lamb’s Instagram posts: “Congratulations @nic_lamb for winning Mavericks. Made me cry. I don’t cry all that often, but when I do it feels really good. Thank you Nic for making me feel good.”

All those years, Brock made it cool to laugh at surfing. Now here he was making it cool to cry. He died on Thursday, at home in Haleiwa, Hawaii, surrounded by relatives.