THE QUEST Hey, rich-guy adventurers like Steve Fossett and Richard Branson: Now that the earth has been circled (twice) by hot-air balloon, whaddya gonna obsess over next? We suggest the Seven Plummets—the deepest, darkest places in each of the Seven Seas. Almost all of these crannies are unvisited by man or probe, and for the first time in history, a small, speedy diving craft has been devised that could take you down and back in hours. All you need is a few million bucks and a hearty appetite for danger. At 37,000 feet, the water pressure is 17,000 pounds per square inch—that’s like stacking three SUVs on your big toe. The slightest crack in your craft would cause it to implode, turning you into plankton-size giblets.

THE VESSEL In 2000, Graham Hawkes—founder of Hawkes Ocean Technologies in Point Richmond, California, and a prolific submersible designer—completed a blueprint for a 5,000-pound “underwater airplane” called Deep Flight II. This battery-powered, ceramic-and-aluminum craft can fly through the water at six knots, withstand 25,500 pounds of pressure per square inch, and descend 500 feet per minute. The only catch: It hasn’t been built yet, because Hawkes can’t raise the dough. “The work is done,” he says. “We’re just stalled on funds.” He needs $5 million to get the thing built. Add an additional $2 mil for incidentals, and you’re ready to go deep. Which seems doable: Fossett spent at least $4 million in his six attempts to circle the globe.

Eurasian Basin, 17,257 Ft.

(Arctic Ocean: 81°20’N, 120°45’W)

Better act fast on this one. Former U.S. Navy sub captain Alfred S. McLaren is leading a team planning a 2003 plummet in a Russian Mir submersible.

Java Trench, 23,376 Ft.

(Indian Ocean: 10°19’S, 109°59’E)

Call it the Deep Muddy. This gloopy trench collects sediment from much of the Indian Ocean, including India’s Ganges River, 2,000 miles away.

Romanche Fracture Zone, 25,780 Ft.

(south atlantic: 0°16’S, 18°35’W)

This spot is paradise for plate-tectonics wonks. Thanks to the wafer-thin surface of the ocean floor, extremely rare rocks from the earth’s lower crust and upper mantle are exposed and accessible.

South Sandwich Trench, 27,312 Ft.

(Southern Ocean: 55°43’S, 25°57’W)

Your challenge here: getting Deep Flight II in the water at all; 50-foot surface swells are not uncommon.

Puerto Rico Trench, 27,493 Ft.

(North Atlantic: 19°42’N, 66°24’W)

Be on the lookout for three-legged fish: Each year between 1973 and 1981, the United States dumped about 121.2 million gallons of chemical waste here.

Tonga Trench, 35,499 Ft.

(South Pacific: 23°16’S, 174°44’W)

Practice saying, “The void down there was huge!” You could fit all of Mount Everest in this trench, with room for a Great Smoky thrown in.

Mariana Trench, 35,827 Ft.

(North Pacific: 11°22’N, 142°36’E)

Deepest spot on the planet. American adventurer Don Walsh and Swiss explorer Jacques Piccard kerplunked it in 1960 in a 366-ton bathyscaphe. They didn’t hit bottom, though, so the nadir is still up for grabs.

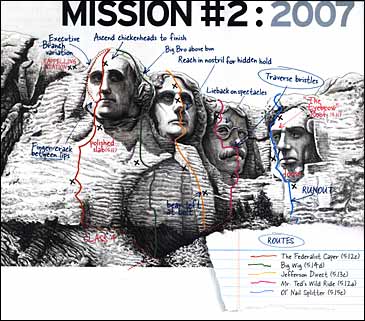

Mission #2: 2007: Free the noses!

They said it shouldn’t be done. Then the world went bonkers for Mount Rushmore National Climbing Park.

WILL “THE PREZ” PEREZ, 22, and climbing partner Anne May, 19, made history over Labor Day weekend when Perez red-pointed Ol’ Nail Splitter (5.15c), the trickiest route posted to date at Mount Rushmore National Climbing Park. Nail Splitter—which follows a dicey Adam’s-apple-to-forehead line up Lincoln’s stony visage—was a grail long sought by climberati, but it had repeatedly stymied the world’s best rock jocks, including Chris Sharma, Tommy Caldwell, and Beth Rodden. Hundreds gathered at the MRNCP to watch Perez’s benchmark ascent, peeping through telescopes and gasping audibly at several near-falls as the wiry North Dakotan spidered into history.

“I had no idea what I was in for,” Perez said later, still jittery about his achievement. “The crux is almost totally blank—the holds are the size of hen’s teeth.”

Mount Rushmore opened to fee-paying climbers on June 1, 2006, capping one of the unlikeliest sagas in the annals of the National Park Service. Originally denounced as a travesty by congressmen on both sides of the aisle, suspicious South Dakotans, and the angry heirs of Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum, the MRNCP became America’s only federally sponsored climbing crag after studies showed that a multi-use approach (sightseeing, climbing, BASE jumping, and the hugely popular HedSplitter Music Festival, held every year “on top o’ the skulls”) would boost Rushmore revenues by a staggering 300 percent. “After that,” says MRNCP superintendent Wally Prokop, “the only thing we heard out of Congress was, ‘Rope up!'”

Since then, some 50 routes have been established, including a few sport-climbing classics. On June 12, 2006, free-climbing ace Dean Potter sent Jefferson Direct (5.13c), despite taking a 30-foot whipper on the notorious Stiff Upper Lip. Caldwell and Rodden red-pointed Big Wig (5.14d) on March 24, 2007, and then flashed the variation Executive Branch (5.12c) the next day. Later that year, speed-climbing phenom Chris McNamara on-sighted Mr. Ted’s Wild Ride (5.12a).

With the final nose now picked, will climbers get bored?

“No way,” says McNamara, who also runs Supertopo.com, producer of the official online climbing map to the park. “There’s so much left to do here, especially if they carve another head. I’m hoping it’s Reagan’s.” Because he was a great president? “Nah. Because that hairdo of his would be at least a 5.15.”

Mission #3: 2015: Going All The Way

Break out your shovels, machetes, boots, and bikes. We’re building a 50,000-mile supertrail around the world.

THE VISION Smart-alecky backpackers will call it the Phileas Fogg Slog, but we prefer the formal name: The Global Greenway, our proposed around-the-planet hiking-and-biking trail. Starting at the northernmost tip of Alaska, this boat-and-plane-connected supertrek would traverse the Americas, hug the northern coast of Antarctica, dogleg across Africa from Cape Town to Tangier, meander through Europe and southern Asia, and cross eastern Australia, north to south. Twenty-three times longer than the Appalachian Trail, the 50,000-mile course would take the persistent hiker roughly 12 years, 132 million steps, and 18 million calories to finish. Phew!

THE ROUTE Earth is a big planet, but we’re already halfway there. If we incorporate existing or in-the-works trails—including the Trans Canada and Continental Divide trails in North America, the Mesoamerican Trail in Central America, the Sendero de Chile in South America, the E3 in Europe, and the Bicentennial National Trail in Australia—the Greenway is nearly 50 percent complete. What’s left is pretty immense, though. Organizers will have their hands full coordinating respective governments and volunteers and, of course, blazing new trail. Building costs will total about $882 million, and money isn’t the only problem. Several regions pose special obstacles.

GETTING IT DONE

Alaska (Trail needed: 1,500 MILES): A path linking Point Barrow with the Trans Canada Trail in the Yukon Territory would zigzag through some of the Last Frontier’s most beautiful wilderness. Environmentalists will have to be persuaded to allow a simple, cairn-marked way through roadless areas and precious caribou habitat.

South America (4,000 MILES): Trail builders will face narco-terrorists in Colombia and active land mines in Ecuador. The good news: 15th-century Inca trails are still serviceable in Peru, and when finished, the Sendero de Chile trail system will mean smooth sailing all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

Antarctica (2,000 MILES): With skis and a GPS, globe-trotters could navigate an unmarked path along the Weddell Sea—from the Antarctic Peninsula to Queen Maud Land—with minimal eco-impact. The 44 nations that jointly govern Antarctica aren’t likely to welcome more than a few through-skiers each year, but if everybody behaves, that could change.

Africa (12,000 MILES): The Greenway will hit major trekking highlights—the wildlife-rich East African Plateau, Mount Kilimanjaro, the Atlas Mountains—while steering clear of the jungly Congo River basin. Searing heat will be the least of trail builders’ worries in Libya and war-ravaged Sudan.

Asia (9,000 MILES): Forging a route from Istanbul to Singapore will largely be a matter of piecing together ancient trade routes and well-worn treks along the Tibetan Plateau. But ornery, heavily armed guards in the Middle East and Southeast Asia—not to mention political conflicts—will make border crossings dicey on even the best of days.

Mission #4: 2027: Mars, Ho!

When we finally knocked off Olympus Mons, the highest peak in the solar system, it took a million small steps…and one giant leap in rocket shoes

WE WERE “MOUNTAINAUTS,” not mountaineers. You don’t scale the highest known peak in the solar system with carabiners and ropes. Mars isn’t Nepal, and Olympus Mons isn’t Everest. It’s 88,000 feet high, the atmosphere is no atmosphere, and 150 degrees below zero is mild. Our giganto space suits, gridded with liquid-food pipelines, heating wires, and A/C ducts—the oxygen-distillation tank and personal sewage system trailing off behind—were so heavy they had to be autogyroscopically balanced to keep us upright.

Purist climbers sneered at the caterpillar NikeWalktrax we wore. But come on, it was 180 miles from the base to the summit, 30 days stomping over hardened lava flow on a shallow grade—more like walking Nebraska than climbing the Himalayas. So why not?

THOSE MECHANICAL YAKS: a bust from the get-go. Overheated under any kind of load, even in that cold, so the mother blimp had to rocket down supplies. Thanks lots. You needed new gloves, you got bass-fishing videos. The box marked “Telemetry Spares” contained a croquet set. Turned out the Russians had done the packing.

THE SUPPLY ROCKETS THEY FIRED DOWN from the mother blimp homed in on an infinitesimal trace of human perspiration. Lethal! Five times a day somebody would start yelling “incoming” in your earphones and you had to start zigzagging like mad. Pretty soon we just stopped asking for supplies. Better to go hungry than be reduced to Martian dust particles.

2002: King of the Road

*

Tour De Stats: Lance Armstrong’s resting heart rate in beats per minute: 32. *Rate of an ordinary healthy adult: 72. *Calories burned riding a Tour de France mountain stage: 6,000. *Lance’s average speed in the 2002 Tour: 24.6 miles per hour, covering 2,032 miles. *Number of miles he cycles every year: 21,000. *Miles covered yearly by a typical car in America: 14,400. *Three-year-old Luke Armstrong’s summary of his father’s race strategy: “Daddy makes ’em suffer In the Mountains.” *Name of Lance’s climbing-stage bike in the 2002 Tour: Daddy Yo-Yo. *Number of Trek bikes used annually by the 21-man U.S. Postal team: 64. *Lance’s 2002 speaking fee: $150,000. *Former President Bill Clinton’s fee: $150,000. *Number of residences Lance has acquired in the past four years: 4. *Favorite downtime fuel: Shiner Bock beer and Hula Hut tubular tacos. *Number of fans who attended summer 2001’s Vive Lance victory party in downtown Austin: 20,000. *Secret hobby: decorating with antiques. *Consecutive Tour de France wins (maybe you’ve already heard?): 4.

Compiled by Alan Coté