Ronnie Simpson ambles up from the docks of the Stockton Sailing Club. At 25, he is whip thin and browned by the Northern California sun. His hair is close-cropped, and he's wearing his preferred uniform: boardshorts and a faded sailing T-shirt. He's in Stockton to take possession of a 28-foot Albin Cumulus sailboat that he just bought for $2,800, with money borrowed from a friend. The boat is called Chippewa, and the cockpit is strewn with tools, gear, and empty beer cans. A dark scrim of weeds encrusts the bottom, but beneath the grime you can see the shape of a blue-water pedigree. Ronnie is taking Chippewa down the San Joaquin River to San Francisco Bay, to the Marina Village Yacht Harbor, in Alameda, where the boat will become his new home. As soon as he feels it's ready to sail to Hawaii and beyond, Ronnie Simpson will do what he does best: take off and see what happens.

Ronnie Simpson

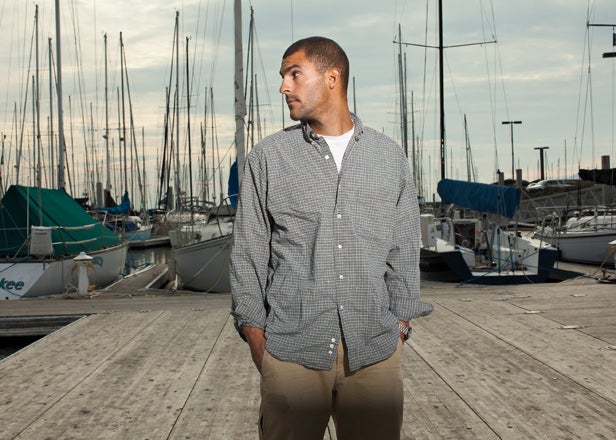

“You get what you give.” Simpson in Point Richmond.

“You get what you give.” Simpson in Point Richmond.Ronnie Simpson in Fallujah

Camp Fallujah, Iraq, 11 days before Simpson was injured. June 19, 2004.

Camp Fallujah, Iraq, 11 days before Simpson was injured. June 19, 2004.Ronnie Simpson's burns

Simpson, burned and sedated, July 2004

Simpson, burned and sedated, July 2004Ronnie Simpson TransPac race 2010

Simpson after crossing the finish line in the 2010 Singlehanded TransPac race.

Simpson after crossing the finish line in the 2010 Singlehanded TransPac race.Ronnie Simpson in San Francisco Bay

Simpson sailing on San Francisco bay

Simpson sailing on San Francisco bayRonnie looks like any boat bum who works odd jobs on the waterfront. He's always up for a party or a deal on Craigslist, and he's not averse to drinking beer within an hour or two of a late breakfast. He has a laid-back, renegade charm and tells stories as easily as he draws breath. He makes friends wherever he goes, and sometimes it's hard to keep track of all the girlfriends (“she was soooooo hot”) who've wandered into his life. It wasn't very long ago that he had just $15 to his name.

But Ronnie is not an aimless vagabond. To understand this, you need to take note of the long, moon-shaped scar under his left arm, which arcs around his rib cage from pectoral to scapula. You need to observe the seven-inch vertical scar that bisects his stomach, deviating only slightly around his belly button. You should also take in the coin-size cicatrices that pepper his torso, pale blotches against the dark of his skin, and try to imagine the searing heat that branded him. Ronnie served as a marine in Iraq, and on the night of June 30, 2004, at age 19, he almost died.

How he got from there to here is a wrenching story, of how war takes human beings, breaks them into little pieces, and gives them two choices: surrender or fight. Unlike many veterans, Ronnie eventually found a way back from his life-threatening injuries, enduring a long hospitalization, the death of his father, and a few years of soul-numbing suburban striving before the accidental discovery of sailing and adventure helped him to reinvent himself. It was an odyssey that almost killed him more than once, but in the end, it also saved him. “I have never been so broke in my life,” he says. “And I've never been happier.”

After a night of ale-assisted slumber in Chippewa's simple cabin, we ease the boat out of the slip as soon as there's enough light to navigate the marina fairway. From Stockton, we've got some 50 miles of motoring down the channels of the San Joaquin River before we're released into San Pablo Bay, and San Francisco Bay beyond. Apart from trying to avoid getting lost in the maze of side channels, pulling weeds off the prop, and wishing there were enough wind to sail, there's not much else to do besides hear the tale of Ronnie Simpson's resurrection.

RONNIE DOESN'T ACTUALLY remember the moment his life was blown apart. He was in a Humvee, bouncing down Highway 11 between Baghdad and Fallujah. The cooling night air was thick with dust and diesel exhaust, and the hard heft of a tripod-mounted 50-caliber machine gun was in his hands. Highway 11 was not a great place to be at 11:30 p.m. on June 30. The Sunni insurgency was in full metastasis, and the radio in the Humvee was chattering with reports of units getting hit all across the country.

Ronnie's platoon, part of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, was helping escort a convoy of Army trucks back to its base. Ronnie was standing in the Humvee's truck bed as they followed a large Army transport. He saw a single muzzle flash flare in the darkness, then another. A fusillade of shots ripped into the convoy, and then a firefight erupted hot and heavy. Ronnie swiveled the 50-cal toward the enemy position and started firing.

The Army truck in front ground to a halt. “Why are we stopping? Why are we stopping?” Ronnie shouted. “Well, the fucking Army stopped,” his commander snapped back. No one knows for sure what happened next. There was a whoosh that sounded like a rocket-propelled grenade, then a white-hot explosion. All Ronnie knows is that the world went black.

Ronnie's body armor and the blast shield gave him some protection. Still, the rapidly expanding burst of hot chemical gas from the munition scorched what it could, melting his night-vision goggles and leaving him with second-degree burns covering 9 percent of his body. He opened his mouthÔÇöin surprise, to breathe, to shoutÔÇöthe unfortunate reflexive response to an explosion. That allowed the hot gas, infused with dust and particulates from the road, to fill his lungs and push his tongue back into his airway. The concussive force tore him off the machine gun and threw him against the back of the Humvee. His head bounced off the truck frame so hard that the retinal layer at the back of each eye ripped away from the underlying tissue.

Ronnie's war was over. He was helicoptered to the 31st Combat Support Hospital, near Baghdad, where he was knocked out with heavy sedatives, intubated, and put on a ventilator to help him breathe. Two days later he was flown to the Army's Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, in Germany, where he was picked up with six other burn casualties by a C-17 plane specially outfitted for long-range evacuation. When needed for a “Burn Flight Team mission,” it flies with a full medical team and all the specialized equipment needed to keep grievously burned soldiers alive long enough to get them to the Brooke Army Medical Center, in San Antonio, Texas. BAMC is the Department of Defense's burn-treatment center, and Ronnie was brought into the ICU on the fourth floor on July 6, 2004, less than a week after being hit.

The BAMC ICU is designed to cope with the worst that explosives and heat can do to a human. Patients' rooms are accessed through an antechamber in which doctors, nurses, and visitors scrub and dress for sterility. The units for the most severe burns can be pressure-controlled to seal out airborne pathogens. Inside these rooms, the wounded lie still, walled in by beeping technology and swathed in dressings. Some are missing facial features, and others have bandaged stumps where limbs used to be.

Lieutenant Colonel Evan Renz, an Army surgeon, is the director of the U.S. Army Burn Center at the Institute of Surgical Research at BAMC. When Ronnie arrived in July 2004, his eyes told the medical team how powerful the explosion had been. “We don't see [double detached retinas], because they don't come here,” Renz told me.

“Because they're dead?” I asked.

“Right,” he answered. “He took a heck of a blast. We never know which of the body systems are going to be affected.”

When Grace Simpson, Ronnie's mother, first saw her son in the ICU, she almost fainted. She could see where his dog tags and chain had burned into him. “My heart sank,” she says. “I didn't even recognize him.” She gently grasped one of his hands and began whispering prayers.

Ronnie endured two major operations and spent almost 12 weeks fighting to recover at BAMC. He was finally discharged on September 27, 2004. Before he got blown up, he'd been a self-confident, 180-pound marine. At one point in the hospital, he weighed 119 pounds. “I wanted to die,” he says. “I looked like a concentration-camp survivor.”

CHIPPEWA'S ONE-CYLINDER diesel is pushing us slowly down a stagnant stretch of the upper San Joaquin River that winds past thick vegetation and deserted dwellings. Apart from the birds, almost nothing is moving. Staring ahead at a confusion of channel buoys, I'm trying to help figure out which way we go.

Ronnie dons a pair of reading glasses and pulls the chart in close to his face. He looks like Mr. Magoo. It's incongruous to see a 25-year-old struggling to read, but Ronnie's damaged eyes are the one thing the doctors couldn't fix. In addition to detaching his retinas, the blast left small holes in his maculas, and cataracts started to cloud the lenses of both eyes. He's had cataract surgery, but his vision is still blurry, and he'll never see properly again. When he went to the DMV to get a driver's license after being released from the hospital, he failed the vision test. “You are 19 and you failed the vision test? How can that be?” the DMV woman asked him. His whole life up until then had been about cars and motorcycles. Now he couldn't see well enough to drive legally. “I started crying,” he says. “That hit me really hard.” (He went back later and memorized the answers others gave to pass, but he still doesn't drive at night.)

His damaged vision also meant he would never be allowed into combat again. Rather than become a military clerk, Ronnie took a medical retirement from the Marines. It came with a $539-a-month disability pension, a partial life-insurance payout, and free medical care for life. Other than that, he was on his own.

Ironically, Ronnie had been OK with going off to war, almost eager. He'd been raised in a patriotic household in Atlanta, in which George Bush was a god and “Democrat” was an epithet. Ronnie's father, Charles, was a descendant of Daniel Boone and a hardworking man, with three car dealerships and some commercial real estate. He did plenty well, and Ronnie, his older brother, R.J., and their sister, Jennie, the eldest, lived a good life. Ronnie and R.J. spent their childhood racing karts and tearing up dirt on their motorcycles. “He was a very wild kid, always doing something crazy,” R.J. says. “He had no fear.”

In January 2003, Charles sat Ronnie down. Operation Enduring Freedom had driven the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, and Operation Iraqi Freedom was an invasion waiting to happen. Ronnie was due to graduate from Northview High School in four months, and Charles had a proposition. R.J. was already heading into the Air Force. If Ronnie would enlist in the military for a four-year hitch and then get a business degree, Charles would start turning over his business to his sons when they got out.

Ronnie didn't think twice. Ten days after he pocketed his high-school diploma in June, he was on his way to Parris Island, South Carolina, for boot camp. In February 2004, a few months after his 19th birthday, he shipped out for Iraq with the 2/2. He wasn't scared. “I actually thought I had like zero chance of getting hit,” he says. “I just didn't think it would happen to me.”

After being discharged from Brooke Army Medical Center in September 2004, Ronnie tried to restart his life. As with many vets, though, his reentry into a society barely touched by war was far from smooth. In November, after convalescing back home in Atlanta, Ronnie went to visit his aunt Lynda and uncle Joe in southern Vermont. His father drove him to the airport. After a few days in Vermont, Ronnie's mother called. “It's Dad,” she said. “He passed away last night.” Charles had died of a heart attack in his sleep, at 55. He'd been working nonstop, including a trip to Japan, when he wasn't visiting Ronnie in the hospital. “Why don't you take a day off and sit around the house with me?” Ronnie had asked on the way to the airport.

For Ronnie's entire life, his father had been the foundation of his politics, his ideals, his take on life. “Just as I was starting to heal physically and mentally from the war, I was emotionally destroyed,” he says.

As Ronnie tells me this, Chippewa's engine note suddenly changes and we catch a whiff of burning oil. The prop has wrapped itself in weeds and grass, overloading the little diesel. Ronnie hits the kill switch, peels off his shirt, and slips over the side into the muddy water to clear it. After he clambers back aboard, we pull out the chart again. We're trying to make it to Benicia, 30 miles away, where the river dumps into San Pablo Bay, before nightfall.

Ronnie is self-assured and navigates with confidence. It's hard to believe he spent the three years after his father died dazed and confused in San Antonio. His ambition of going into the family business had died with Charles. Instead he waited tables, then quit and began working for a motorcycle dealership, Alamo Cycle-Plex, planted among the mattress stores and car lots along I-10. He attended community college. He met a girl named Amanda and spent a big chunk of the cash he'd received after his father's death and from the life insurance on a house in northwest San Antonio. He expected he and Amanda would get married. He buried himself in work and school, as if free time were a black hole of introspection that would cause more pain. Grace could tell something wasn't right. “I thought he was very, very lost,” she says.

The only real pleasure he had, Ronnie says with a grin, was riding his sport bike, a lightning-quick 2007 Suzuki GSXR 750. The commute from his home to the Alamo Cycle-Plex took him over a ten-mile stretch of Highway 1604, a four-lane divided motorway that curves around the north side of San Antonio. Speed, and the freedom of a fine machine running flat out, were a release. After work, Ronnie would hit the highway and wind the bike up to 130, 140, 150, flashing past barbecue pits, self-storage units, peeling billboards, and mini-malls.

One day a couple of police cruisers tried to trap him, and he ran a roadblockÔÇöpractically daring two cops with guns drawn to take a shotÔÇöbefore escaping. As the adrenaline started to ebb, he realized he was riding with suicidal abandon, risking his life for nothing. That realization led to another: he hated the nonstop work, the routine, and the feeling that the walls were closing in on him. “I wouldn't say I had a breakdown,” he says. “But I had a moment of reckoning, where I said to myself, Ronnie, you don't care if you live or die.” He knew he had to escape. He just wasn't sure how.

A few months later, on December 18, 2007ÔÇöhe remembers the exact date without hesitationÔÇöhe was at home, trying to relax after work, when the phone rang. It was R.J., back from a tour in Afghanistan and now based in Hawaii. “In a few years, when I get out of the Air Force,” he told Ronnie, “you and I should sail around the world.”

NEITHER R.J. NOR RONNIE had ever sailed before. But for Ronnie, the idea was a lifeline. Into the wee hours of the night, he clicked his way across the Internet, reading about sailing and the oceans, looking at sailboats, and imagining what kind of vessel he might choose. He thought about his father, who never really had a chance to enjoy his success. “He was a great provider and a great guy,” he says. “But I didn't want to follow in his footsteps.”

Five days later, Ronnie had a For Sale sign up in the front yard. He told Amanda they were through: he would be quitting his job, giving up on college, and moving away. “I'm sorry,” he said. He began making plans to go to California, buy a boat, and sail it around the world. For the first time in a long time, he had purpose, and he wasn't prepared to wait around for R.J., who had three more years in the service. Instead Ronnie would visit R.J. in Hawaii, as a first stop. By February he had put a deposit down on a 41-foot Palmer Johnson Bounty II, called La Cenicienta (“Cinderella”), located at San Diego's Marina Cortez, on Harbor Island. Three months after R.J.'s call, Ronnie sold almost everything he owned and moved to San Diego.

La Cenicienta was a sturdy fiberglass classic, built in 1961 to go anywhere. He'd found it online, and it cost him $30,000. He sank another $20,000 or so into engine repairs, safety equipment, and upgrades. He started a blog, and on July 1, a day after the four-year anniversary of his injury, he wrote, “I can honestly say that, for the first time ever, I am genuinely happy with where my life is headed.”

On October 1, 2008, Ronnie set sail across the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii. He'd read instruction books, starting with Sailing for Dummies, and had practically taken up residence on Internet sailing forums, asking questions and soaking up advice. He'd crewed on local race boats to accelerate his education. But he'd spent only a few nights at sea, mostly drifting around with no wind. Some of the old salts who lived at the marina and spent more time working on their boats than sailing them shook their heads and warned him about avoiding a departure in October, which is the tail end of the Pacific hurricane season. Ed McCoy, a professional delivery skipper and boat captain who'd become Ronnie's mentor, had no illusions about how steep his young buddy's learning curve was. “He knew fuck-all about sailing,” McCoy says.

Ronnie wasn't worried, though. It was 2,500 miles to Hawaii, but he had an Aries self-steering wind vane (which he nicknamed Chuck Norris) to handle most of the helming. It used the wind angle, and the power of the water flowing over a small rudder, to steer via control lines connected to the steering wheel. He also had a good life raft, an emergency position indicator beacon (EPIRB), and e-mail and weather-forecasting capability via his single-sideband radio. The nuances of voyaging, he figured, could be learned at sea.

Ronnie went to sea with the same optimism and indifference to risk he'd carried into Iraq. The ocean was no more forgiving. A week into the trip, Chuck Norris kept breaking down, making it hard for Ronnie to get much sleep. Rough weather ripped away a sea kayak he'd lashed on deck and turned over a gas can that had unwisely been stored below. Pungent fumes colonized the interior of the boat, making Ronnie sick. “The ocean is sneaky,” he wrote in his daily log. “It keeps you on your toes.”

Any sailor who's attempted an ocean crossing knows how lonely it can be on board a small boat navigating a vast stretch of gray, inhospitable sea. Five days into his crossing, the Pacific confronted Ronnie with the outer bands of Hurricane Norbert, which arrived with 35-knot winds and 25-foot seas. Mountainous, foaming waves rolled up, one after the other, battering La Cenicienta. One surged up over the side and smashed Ronnie against the cockpit coaming. The wind tore at the sails and hammered at him when he came on deck. “I absolutely cannot believe the power that the ocean possesses,”ÔÇłhe wrote. “This is insane.”

After dark on his eighth day, the boat suddenly veered sharply off-track. The steering oar on Chuck Norris had somehow snapped off. San Diego was 700 upwind miles behind him; Oahu lay another 1,585 miles ahead, and he had no more self-steering. “This is one of the worst nights of my life,” he wrote. “I am beginning to fear for my own safety.”

The next morning, it got worse. He discovered that La Cenicienta's aging rudderpostÔÇöwhich had connected the rudder to the steering wheel via a quadrant and worm gearÔÇöhad also sheared clean through. Now he had no steering of any kind, even with his emergency tiller. His boat was crippled. He glanced down at his watch. It read 9:11 a.m. Nine-one-one, he thought. Emergency.

An hour later, a big wave knocked La Cenicienta onto its side, and Ronnie had finally had enough. He thought about how he'd almost died in Iraq; he didn't want to die at sea, even if it meant abandoning everything. He wrote an e-mail to R.J. and sent it over the single-sideband radio: “This is the lowest I've ever been ÔÇŽ i am not prepared to drift and drift through hurricane alley until i hit land. the f*&^* rudder post sheared off. there is nothing that i can do. i almost rolled over. get me rescue asap.”

As evening approached on Thursday, October 9, the M/V Vecchio Bridge, a massive, 961-foot Japanese container ship, appeared out of the gray and the fog. The Coast Guard, alerted to Ronnie's request for rescue and tracking La Cenicienta's position via his EPIRB, had requested the ship divert from about 75 miles away. Just as dark started to fall, RonnieÔÇöclinging to a life ring, with his passport, two cameras, a computer, and a single change of clothes stuffed into a backpackÔÇöwas swung aboard. The throb of the Vecchio Bridge's engines increased as it started to accelerate toward its next destination, Shanghai. La Cenicienta faded into the blackness. Within a month it had drifted 600 miles toward Hawaii, where a cruise ship spotted it. After that, it was never seen again.

ONE MONTH LATER, on November 6, Ronnie walked into the Flying Ball Bicycle Shop, in Hong Kong's Kowloon district, and bought a 2009 Cannondale Caffeine F3 mountain bike. He'd made his way from Shanghai to Hong Kong, hoping to buy another boat. Nothing seaworthy was even remotely affordable. “There was no way in hell I was going to take off from Hong Kong in some $4,000 piece-of-shit sailboat,” he says as Chippewa approaches Alameda.

A bicycle seemed like an obvious alternative. For less than $2,000, he could continue his circumnavigation. His plan was simple: leave Hong Kong on January 1, 2009, and ride west until he hit the Atlantic. “I thought it was crazy. Who rides a bike across a continent?” says R.J., who is now out of the Air Force, married, and still living in Hawaii. “You have no protection. You don't know anyone and don't know how they are going to treat you. It was very ballsy.”

Over the next seven months, Ronnie pedaled more than 8,000 miles, across China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, India, Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Slovakia, Austria, Germany, Holland, Belgium, and France. He was knocked down, run off the road, and clipped by a truck. He also experienced extraordinary kindness and hospitality, again and againÔÇölike the day when he was lost near the southern coast of China and an old man on a bicycle gathered his friends and escorted Ronnie for hours to his destination, eating and drinking with him along the way. He camped under the stars, ate mountains of rice, and lived on just dollars a day, collecting his $539 military retirement benefit each month, sometimes just as he was going broke.

“It was the most beautiful experience of my life,” Ronnie says now. “I was extremely content because of what I was doing and not because of the things I had. It confirmed everything I thought about life. That trip became me, and I became that trip.”

In early July 2009, Ronnie rolled into London and the odyssey came to an abrupt end. After meeting a friend for a pub lunch, he walked outside to discover his bike had been stolen. “Losing that bike really hurt,” he says. “I put ten times as many miles on it as I did on the boat.”

He didn't give up, though. He bought a beater bike for $200 and rode it to the U.S. Air Force base at Mildenhall, 80 miles north of London. From there he hitched a military transport plane to a base near San Francisco and pedaled down the coast to San Diego. As he crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, he was mesmerized by the way the ocean breezes funneled into San Francisco Bay. He felt a powerful urge to sail again.

Ronnie arrived back in San Diego almost ten months to the day after setting out on La Cenicienta. He had $88 in his pockets and less than $200 to his name. It wasn't exactly what he'd planned, but he'd circled the globe.

Even before his bike tires stopped rolling, though, Ronnie turned his mind to unfinished business: to complete a solo passage to Hawaii. But this time he had a more audacious plan. He would race in the 2010 Singlehanded TransPacific Yacht Race, from San Francisco to Kauai, the premier competition for West Coast solo sailors. He got a construction job to earn fast money and bought a solid little Cal 25 off Craigslist for $1,000 to live aboard and prep for the race. “One chapter had closed,” he says. “My plan now was to work every day toward the goal of competing in the 2010 Singlehanded TransPac.”

Eleven months later, on July 4, 2010, Ronnie came up on deck to blue skies and fair winds. He was on his way across the Pacific again. Instead of the Cal 25, he was aboard a 30-foot custom race boat, called Warrior's Wish, that had been loaned to him by another solo racer, a Vietnam veteran who had read about Ronnie on a sailing Web site. As he'd sailed to the start line on June 19, the memory of abandoning La Cenicienta wouldn't leave him. “I was terrified,” he says. “Those demons came back, and I only exorcised them by starting the race.” For the first week out of San Francisco, in snotty 35-knot winds, he'd battled hard for the lead, before sailing into a windless area of high pressure and slipping into second place.

After the 9 a.m. radio check-in with race organizers, Ronnie raised the big masthead spinnaker. The breeze started to build, from 15 to 25 knots. He cranked up his iPod, rocking to Rage Against the Machine and Tool, and settled in on the helm as Warrior's Wish went faster and faster. The Pacific swells rolled up behind him, launching the 6,000-pound boat on long, hissing surfing runs.

At 28 miles out, 16 days into the crossing, he could clearly make out the northeast shore of Kauai, rising from the Pacific into a towering volcano of black rock. Warrior's Wish crossed the finish line at Hanalei Bay sixth overall and second in class. The VHF crackled. “Congratulations, Warrior's Wish, you have just finished the Singlehanded TransPac. Welcome to Hanalei.”

It's over, Ronnie thought. This is it. I did it. Feeling a wave of emotions that coursed all the way back to that explosive night in Iraq, he picked up his radio. “Thanks” was all he could manage. A small Boston Whaler raced out to greet Warrior's Wish. R.J. was the first to jump aboard.

I'M SITTING WITH RONNIE on the patio of a caf├ę at Marina Village Yacht Harbor, overlooking the docks that serve as his neighborhood. We pulled in late yesterday afternoon, after two days of motoring and sailing. Before we were even properly tied up, Ronnie couldn't resist hopping into a little sailing pram that his buddy Tony had bought on Craigslist for $300. Now we're drinking coffee and eating breakfast on a cool San Francisco morning, with the promise of breeze later.

Completing the Singlehanded TransPac was a redemption on many levels, but Ronnie grins and tells me there is a postscript. On the return from Hawaii, with his sailing mentor, Ed McCoy, along for the ride, there was a mysterious pop-pop-pop. It turned out to be the sound of Warrior's Wish's keel falling off. Most sailboats without a keel immediately turn upside down. Warrior's Wish somehow remained upright, though unstable, but there were another 800 miles to San Francisco. They couldn't sail, because wind pressure would capsize the boat. So Ronnie and McCoy, using spare diesel fuel dropped by a passing vessel, managed to motor all the way back to San Francisco. They made a triumphant return through the Golden Gate at four in the morning and were welcomed by a fleet of friends armed with beer and Thai takeout. “It was a bad experience, but I never felt so alive,” Ronnie admits. “When I got back to the Golden Gate, it was absolutely the best feeling I have ever had.”

I realize that's what Ronnie is about: feeling alive. It's a reaffirmation that he survived, but also a way to avoid wasting time in a life that has taught him there are no guarantees. To get that feeling, he puts himself out there, pushing the boundaries, constantly seeking new experiences. Playing it safe, and trying to live as long a life as possible, isn't really living to him. “You only get what you give,” he tells me.

That makes him a candidate for the usual bucket-list adventures, like the Iditarod or the Baja 1000, and he reels those off as goals. But his real aim is more personal. Chewing on his breakfast burrito, he says he wants to sail in the around-the-world Vend├ęe Globe race. It's solo, nonstop, and takes sailors through the vast, frigid wastes of the Southern Ocean, where the wind and waves on most days exceed the little blow that forced him off La Cenicienta. It's flat-out the most grueling, dangerous competition a sailor can enter.

The Vend├ęe sets off every four years, and it's an acid test of will and skill that only two Americans have ever completed. (French sailors dominate.) Ronnie has started to map out his plan for entering the 2020 Vend├ęe, a suitably audacious ambition. He knows it, and a smile appears. “You shouldn't spend your entire life trying to fit into the system,” he says. “You shouldn't just take your place in society and do nothing. The world is huge. The world is awesome. The world is to go out and explore.”

Before I leave, I ask him whether it might all seem a bit self-indulgent. He practically flinches, and then starts talking in a low voice about the hopeless void that sucks wounded veterans down, and says he'd eventually like to teach vets how to sail. He describes an imaginary marineÔÇöonce fit, with a beautiful young wife and a bright future, but now disfigured or missing limbs. “That guy is broken down and thinks he has nothing to live for. He might be turning to alcohol, beating his wife, or thinking of committing suicide,” he says.

The memoryÔÇöof how he felt, of how the other patients he saw in rehab feltÔÇöchokes him up, and now the words come slow and tight. “But you could take his one good hand and put him in a boat and teach him how to sail and race. After that, he could go to the bar and have some beers, and he'd be, 'Dude, I just competed and now I'm drinking with my buddies.' He is going to say, 'Yeah, I can do anything.'”