BIG WAVES—those 50 feet high or more—have existed as long as the ocean itself, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that surfers began playing in them. The test pilot, of course, was Laird Hamilton, the redwood-size waterman. With a crew of buddies, Hamilton began exploring the outer reefs of Maui with jet skis, since the monster waves moved too fast to paddle into. Big-wave riding remained the purview of a small tribe until 2001, when Billabong offered a $500,000 prize to any surfer who rode a 100-foot wave. The money unleashed an army of surfers on a global odyssey to find the winning wave, and that quest led to some big questions: Was it possible to ride such a beast? And, more important, did hundred-foot waves even exist?

Slippery When Wet

Having exhausted trout as a subject (seven books!), writer and illustrator James Prosek turns to the freshwater eel in Eels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Mysterious Fish (Harper, ). The 50-million-year-old species wouldn’t seem a likely subject for a riveting natural-history book—it is covered in slime, after all—but Prosek pulls it off, thanks mostly to the rabid eel aficionados he digs up. Take Ray Turner, a recluse in New York’s Catskill Mountains who annually rebuilds his stone-weir eel trap by hand, or Daniel Joe, a New Zealand Maori pig-hunting guide who views the native eel’s struggle with British-introduced trout as a metaphor for colonialism. Occasionally Prosek goes too far down the path of anal…The Wave

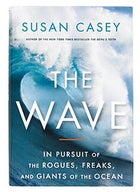

Susan Casey's The Wave

Susan Casey's The WaveIn The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean (Doubleday, $28), former ���ϳԹ��� creative director Susan Casey pursues those questions with tenacity and literary grace. Casey’s sharktastic bestseller The Devil’s Teeth announced the debut of a powerful voice in adventure writing, and her follow-up does not disappoint. The narrative drive comes from Hamilton, whom the author follows at Maui’s offshore break Jaws and Tahiti’s monster Teahupoo. Those hoping for a critical look at Laird won’t find it here: Casey portrays Hamilton as a visionary, seeking not just outsize waves but an ever deeper understanding of the physical and spiritual forces that create them. For him, the big-wave prize did nothing but bring bad karma and jet-ski-crashing yahoos to the water. “As soon as Billabong put the golden carrot up, that was when the carnage started,” he says. “Everyone came out of the woodwork to get their shot at it.”

Casey also delves into the science of big waves and their effect beyond the wetsuit crowd. Rogue waves, which occur in open seas and are different from the monsters Laird hunts, can actually reach 150 feet. They occasionally rip freighters in half, and one section of Alaska’s coast sees waves that are hundreds of feet high and mow down forests. These aren’t once-in-a-lifetime events: Rogue waves, once consigned to the realm of myth, are now acknowledged as one of the major reasons that large ships regularly go missing in open seas.

Casey’s writing on wave forces and maritime disasters is masterful on its own, but what shines here is her portrait of the epic winter wave season of 2007–08, when some of the biggest rollers ever recorded hit shore and a scruffy crew of riders and surf photographers followed, from Jaws to Maverick’s to Todos Santos. In the end, Hamilton claims to find and ride the 100-foot monster, somewhere off the coast of Maui; all he’s got are a few witnesses, no photos. Perfect, in a way.

BY OUR CONTRIBUTORS

Rowan Jacobsen delivers a locavore’s bible with American Terroir (Bloomsbury USA, $25), both a fascinating, recipe-sprinkled guide to our most important “flavor landscapes” and a chronicle of the author’s quests to find the most sublime honey, coffee, oysters, chocolate, salmon, mushrooms, wine, cheese, etc., that the country has to offer.

Benjamin Percy’s debut novel, The Wilding (Graywolf Press, $23) is the story of a grandfather-father-son hunting trip gone wrong in central Oregon. The book’s casualties include the father’s spirit; the boy’s innocence; many animals, of the scaled and furry and grizzly varieties; and, most poignantly rendered, a wilderness doomed by a golf-resort development.