It was so quiet.

Tsangpo River

From left to right: Johnnie Kern, Allan Ellard, Mike Abbott, Willie Kern, Scott Lindgren, Dustin Knapp, and Steve Fisher

From left to right: Johnnie Kern, Allan Ellard, Mike Abbott, Willie Kern, Scott Lindgren, Dustin Knapp, and Steve FisherDustin Knapp, Tsangpo River

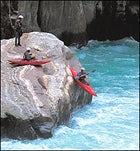

Dustin Knapp shows off his best seal launch

Dustin Knapp shows off his best seal launchScott Lindgren, Tsangpo River

Sat phone in hand, Scott Lindgren runs the show

Sat phone in hand, Scott Lindgren runs the showSteve Fisher, Tsangpo River

“Quality whitewater”: Steve Fisher threads the Tsangpo’s Class V froth

“Quality whitewater”: Steve Fisher threads the Tsangpo’s Class V frothAllan Ellard, Tsangpo River

Allan Ellard drives through a treacherous hole

Allan Ellard drives through a treacherous holeNamcha Barwa

The only was out is up: The view of Namcha Barwa

The only was out is up: The view of Namcha BarwaTsachu camp

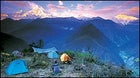

Sunrise over Tsachu camp

Sunrise over Tsachu campDustin Lindgren, Po Tsangpo

Dustin Lindgren on a cable crossing above the Po Tsangpo

Dustin Lindgren on a cable crossing above the Po TsangpoTsachu, Tsangpo River

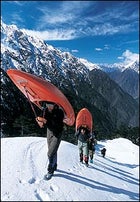

The new porters shoulder the load into the village of Tsachu

The new porters shoulder the load into the village of TsachuGogden Village, Tsangpo River

Hostile territory: The porters riot in Gogden Village

Hostile territory: The porters riot in Gogden VillageThe only sound was the wind, rippling and snapping the prayer flags that ran down the riverbank, freezing the paddlers’ hands as they zipped into drysuits. It came from upstream, from flat across the Tibetan Plateau, and it drove dry snowflakes onto the beach and darkened the jade-green water with patterns like woven fabric.

The kayakers moved quicklyÔÇöpulling on life vests, helmetsÔÇöand didn’t speak. After ten years of planning, there wasn’t much to say. They were seven of the best expedition paddlers in the world. Led by Scott Lindgren of Auburn, California, the young men represented the vanguard of river exploration, and they had come to Tibet to attempt the first whitewater descent of the Tsangpo Gorge, arguably the last great adventure prize on earth.

The gorge was a Himalayan chasm so shrouded in mystery and danger that a legendary waterfall in its depths, sought by explorers for more than a hundred years, was never even photographed until late in the 20th century. And it was a place, like Everest, that shimmered with mythic lore and menacing superlatives. By some measures, it is the deepest river gorge in the worldÔÇöthree times deeper, with the river tilted eight times steeper, than the Grand Canyon. Running close to a thousand miles from west to east across Tibet at roughly 10,000 feet above sea level, the Yarlung Tsangpo enters the gorge and loses almost all of its altitude in a thundering 150 miles. Along the way, it carves a deep channel between the great peaks of Namcha Barwa (25,446 feet) and Gyala Pelri (23,462), which stand only 13 miles apart. To Buddhists, the gorge is the site of mystical portals to sacred realms; some ancient texts say it will be the last refuge of Buddhism when the rest of the planet falls apart. In an age diminished by the belief that there are no great explorations left undone, the Tsangpo Gorge has remained a fearsome, inviolate anomaly. Nobody had ever successfully paddled the 44-mile stretch of the Upper Gorge from the town of Pe to Clear Creek (beyond which waterfalls make the gorge impassable). No one had ever traveled the length of the Upper Gorge at river level. It is possible that parts of the gorge had never been seen by a Westerner.

And now, a few miles downriver from Pe, Lindgren and the other paddlers of the ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Tsangpo Expedition carried their kayaks across a wide beach and set them in the sand at water’s edge. Here the river was calm and flat, but that would soon change dramatically; the team knew that they were about to attempt an unheard-of combination of high-volume whitewater and vertiginous steepness. The last expedition to seriously attempt the TsangpoÔÇöan American group led by paddler Wickliffe Walker in 1998ÔÇöhad made it 27 miles when one of the team, seasoned kayaker Doug Gordon, drowned in violent rapids.

If anyone could get it done, it would be these seven. Most of them had kayaked since they were children, and each now paddled close to 200 days a year. Lindgren, 30, is the alpha male of expedition kayaking, an Emmy-winning adventure filmmaker who has spent much of the past decade pulling off fast-and-light first descents of some of the Himalayas’ most daunting rivers: the Sutlej, the Thule Bheri, the Upper Karnali. His speciality has been river runs combining maximum remoteness, daunting logistical challenges, and extreme audacityÔÇöand he’s done much of his paddling while hauling a 20-pound Bolex movie camera. He has an improbable and perfect record for bringing everyone home alive and intact.

For the Tsangpo team, he picked his closest kayaking friends, all veterans of previous Lindgren epics. South African Steve Fisher, 26, is known for his prowess in big, violent water. Mike Abbott, 29, from New Zealand, and his paddling partner, Englishman Allan Ellard, 27, are famed for their wild descents, many in the Himalayas. Dustin Knapp, 24, of Jacksonville, Oregon, is the star of many of Lindgren’s extreme paddling films; he has launched off so many hair-raising waterfalls and giant drops that he’s stopped counting. Twin brothers Johnnie and Willie Kern, 30, from Stowe, Vermont, have a reputation for fearlessness that has spun off its own catchphrase: “If the Kern brothers won’t run it, nobody will.”

At water’s edge on the Tsangpo, just a few miles before the river begins its plunge, the paddlers snugged down into their tightly padded cockpits like fighter pilots and sealed the openings with their neoprene spray skirts. One by one, they picked up their paddles, shoved off the sand, and glided out on the near-freezing current that divided black-timbered ridges rising above 12,000 feet.

Three Tibetan women from a village just up the hill stood nearby on the sand. They wore belted ponchos of yak skin and watched with the solemnity of mourners at a funeral. Knowing what the seven young men would face downstream, they might have seen it that way.

THE YARLUNG TSANGPO is one of four major rivers that flow off the slopes of Mount Kailas in western Tibet, a peak holy to Buddhists and Hindus and Jainas. It drains the north slope of the Himalayas, then abruptly bends south and shears across the mountain barrier and plunges down toward India, where it becomes the Brahmaputra. In its hidden course through the mountains, the river and its tributaries carve the Tsangpo Gorges. Just before the main current sweeps around “the Great Bend,” it is joined by the Po Tsangpo flowing in from the north. From here the Yarlung Tsangpo crashes through its Lower Gorge (which has also never been run) on its way to the Indian border, about 100 miles away. In its southern reaches, the Lower Gorge cuts through dense, subtropical jungle haunted by tigers.

Cradled in the Lower Gorge is a region called Pemak├Â. An ancient Buddhist text unearthed by a lama in the 17th century declares, “Just taking seven steps toward Pemak├ with pure intention…one will certainly be reborn here. A single drop of water or a blade of grass from this sacred placeÔÇöwhoever tastes itÔÇöwill be freed from rebirth in the lower realms of existence.” Tibetan Buddhists believe that the Great Bend is home to the goddess Dorje Pagmo, “The Diamond Sow,” Buddha’s consort. The gorge is her body, the surrounding peaks her breasts, and the river her spine.

The mysteries evoked by the Tsangpo’s disappearance into the gorge and the Brahmaputra’s emergence below inspired not only myth, but also scientific curiosity. By the 1870s, a controversy was raging among the British members of the Royal Geographical Society and the Survey of India over the unknown course of the Tsangpo. There were rumors of a waterfall the size of Niagara or Victoria Falls. Some thought the Tsangpo’s waters must drain into the Irrawaddy, while others bet on the Brahmaputra.

Tibet was closed to European travelers, but in 1880 the Survey dispatched a pair of Tibetan-speaking secret agents to find out. One was a Chinese lama; the other, a tailor from Sikkim named Kintup, who traveled disguised as a pilgrim. His mission was to surreptitiously map the gorge; he carried a handheld prayer wheel that was equipped with a hidden compartment for a prismatic compass and a thermometer. Once he penetrated the gorge as far as possible, he was supposed to float 500 specially marked logs down the river. If members of the Survey successfully retrieved any of the logs below on the Brahmaputra, it would settle the tributary debate once and for all.

In 1881, Kintup and the lama reached the storied monastery at Pemak├Âchung, in the very heart of the gorge, beyond which no one ever ventured. They backtracked northward, but the lama betrayed Kintup and sold him into slavery. Kintup bided his time for more than a year and escaped in 1883, whereupon he finally threw the logs into the riverÔÇö50 a day for ten days. But by this time the watchers downstream had returned to England.

Two more notable attempts were made to penetrate the gorge in the early 20th century. In 1913 Captain F. M. Bailey, a dauntless British pheasant hunter, made it more than 40 miles in, afflicted by leeches, fever, cuts, and near starvation, before turning back. And then, in 1924, a remarkable botanist-explorer from Lancashire named Frank Kingdon Ward, accompanied by Jack Cawdor, a British nobleman, struggled on hunters’ trails through the Upper Gorge. They discovered a stunning waterfall that they christened Rainbow Falls, crawled straight out over a high pass called Senchen La, and dropped into the tropical Lower Gorge, becoming the first outsiders to traverse the Tsangpo Gorges.

“Every day the scene grew more savage; the mountains higher and steeper; the river more fast and furious,” Ward wrote in his 1926 book, . “Had we finally emerged onto a raw lunar landscape, it would scarcely have surprised us.”

Recent exploration has almost always resulted in controversy, and in some cases death. In 1993, a Japanese kayaker named Yoshitaka Takei put in near the confluence of the Po Tsangpo, at the northern apex of the Great Bend, and perished in the first mile. That same year, filmmaker David Breashears and photographer Gordon Wiltsie attempted to traverse the gorge on foot and caught a glimpse of the mythic Hidden Falls before deciding to turn back. In 1998, the National Geographic Society sponsored two expeditions to the Tsangpo. The first, an overland group led by a pair of Americans, Tibet scholar Ian Baker and Minnesota-based Tsangpo afficionado Kenneth Storm Jr., surveyed and measured the spectacular 110-foot Hidden Falls. The announcement of their findings led to bitter protests from Chinese geographers, who had been exploring the gorge since 1973 and had photographed Hidden Falls from a helicopter in 1987. The second was the ill-fated Walker expedition, which had ended after Doug Gordon died. Walker’s team of four paddlers were much criticized for attempting a descent in October, with the river running at a post-monsoon high, a level that many in the paddling community considered suicidal. The Walker group made another critical decision: to travel with a minimal support crew carrying supplies on land. Consequently, many days’ worth of provisions had to be packed in their boats, making the kayaks ungainly and hard to maneuver.

On Scott Lindgren’s previous Himalayan exploratories, he too had traveled lightÔÇöa few friends, a few porters where needed, boats stuffed with food and gear. Five months before the Walker expedition met with disaster, Lindgren and paddling partner Charlie Munsey had hiked down the Po Tsangpo to the confluence, intending to drop into the Tsangpo and poach a first descent of the Lower Gorge. Although they succeeded in paddling a few miles on the Po Tsangpo, they decided that taking on the huge torrent of the main river was folly.

Over the next three years, Lindgren devised an ambitious strategy that he believed would give him a shot at nailing first descents of both the Upper and Lower Gorges in a single expedition. First, he’d need light boats, which meant a substantial support team to carry food and gear. Second, the expedition needed the resources to operate carefully, methodically, and independently for up to 50 days. Third, he concluded that the only reasonable time to attempt the Tsangpo would be in midwinter, between the monsoon rains and spring runoff. If the expedition could be timed when the Tsangpo was flowing at its rock-bottom low, he might have a chance.

It would be expensive, so Lindgren, a maverick by temperament, knew he’d have to secure major corporate sponsorship to pay for a small army of porters and expedition personnelÔÇöan old-fashioned supply line numbering nearly a hundred people able to sustain themselves for weeks on end. The size of the group and the duration of this trip, he realized, would turn the job of securing visas and permits from Beijing into a complicated and protracted diplomatic struggle.

To fulfill his dream of a 21st-century adventure, Lindgren knew he would have to launch the kind of grand, 19th-century-style expedition that had become obsolete some 50 years earlier. Lindgren had made several films for ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Television, this magazine’s broadcast division, and now he signed on to produce a documentary on the Tsangpo expedition for OTV. General Motors agreed to become a major sponsor, and the Explorers Club endorsed the project as well. In mid-January, after nearly a year of intensive preparations, the team departed from San Francisco, ready for whatever fate held in store.

THE FIRST RAPIDS were boulder gardens, with plenty of room to maneuver. Still, the hydraulicsÔÇödeep troughs capable of trapping kayakers in their backwashÔÇöwere immense. The river was not only powerful but cold, about 40 degrees. Despite full drysuits, helmet liners, and neoprene gloves, submersion in one of these holes would shock the exposed face, numb the head, and quickly sap the body of energy.

It was almost nightfall on day one when the paddlers came to the first serious drop, a broad left bend falling steeply through a series of big holes. The first three kayakers, Abbott, Ellard, and Willie Kern, charged the rapids and cleared a first set of hydraulics. Then Kern swept down. The chaotic current pushed him too far to the right and flipped him; he rolled up too late to avoid one of the massive holes. He disappeared. After what seemed like a dangerously long time, he burst out of the foam, shook his head clear, and then sprinted left and rode into green water. Dustin Knapp came around the corner and did the same thingÔÇöexcept when he dropped into the hole, the river shot him 40 feet to the right and ejected him upside down. He recovered quickly and joined Willie in the flatwater at the bottom.

The plan was to paddle 44 miles through the Upper Gorge to Clear Creek, a point beyond which the river squeezed between towering walls and poured over the two great cataracts, Rainbow and Hidden Falls. From Clear Creek, the whole expedition would climb almost 5,000 feet straight up to traverse Senchen La, a feat that had never been attempted in the dead of winter. Weather, snow conditions, and avalanche danger were all unknown. On the other side of Senchen La was the Lower Gorge, where the kayakers would scout and paddle as much of the massive flow as they couldÔÇöabout 20 miles if they were lucky.

That evening the paddlers and the support expedition camped at the bottom of a terraced pasture below a tiny hamlet called Tripe, about four miles from the put-in. The mood around the fire was quiet, reflective.

“I learned one lesson today,” Knapp said, pulling his head through the latex neck gasket of his drysuit. “To scout for myself when I’m not sure.”

Mike Abbott, the Kiwi, sipped tea, his hoop earring glinting in the firelight. “The first day was a bit intimidating,” he said, “feeling the power of the river.”

Lindgren, brooding on the first hit of the Tsangpo’s muscle, said little. “I want everyone on edge,” he told the kayakers. “One fuckup out hereÔÇöoneÔÇöand the whole thing’s over.”

While the paddlers had been taking the measure of their challenge, the ground crewÔÇö80 strong, including meÔÇöhad spent the first day snaking along ancient game trails on the precipitous right bank of the river. The group was under the supervision of Himalayan outfitter and river guide David Allardice, a 44-year-old New Zealander based in Kathmandu. In addition to his own squad of five Nepalese climbing Sherpas, Allardice had recruited 68 Tibetan porters in Pe. Andrew Sheppard, a 29-year-old mountaineer and extreme skier from Banff, was in charge of technical climbing. Ken Storm Jr, 50, who had surveyed Hidden Falls in 1998, was the expedition’s expert on the natural history and culture of the gorge. Idaho native Charlie Munsey, 34, was trekking on foot this time as the expedition’s photographer. Dustin Lindgren, 27, Scott’s younger brother, was along as a videographer. The support expedition was hauling 2,000 freeze-dried meals, 220 pounds of potatoes, and 60 pounds of chocolate and energy bars. They carried yak jerky, oranges, onions, medical gear, snowshoes, ice axes, rope, radios, satellite phones, a laptop computer loaded with precisely detailed satellite images of the river, and a generator and solar panel to power the phones.

The satellite maps had been a great boon. Back in Auburn, where Scott Lindgren lives and runs his film-production company out of a long, low, cream-colored bungalow, the kayakers had spent dozens of hours poring over every mile of river. Allan Ellard hunched his six-foot-two frame over a computer screen for days on end, piecing together images provided by Space Imaging of Thornton, Colorado, his blue eyes blurring and his blond dreadlocks hanging over his face. There were long sections of river that seemed “blown out” with rapids threshed completely white from bank to bank. Willie Kern had found black-and-white photographs of rapids taken by Kingdon Ward in 1924, and excitedly tried to correlate them with the satellite shotsÔÇöa bizarre juxtaposition of technologies.

“You know you’re screwed when you’re scouting from space,” Ellard had said. He was only half joking.

YOU PADDLE OVER THE TOP of a big wave in Class V water and for a split second you get a view downstream. It’s chaos, a continuous crash. Giant rocks loom, and lateral waves pile and roll off the boulders like the bow wake of a ship. You see shaped humpsÔÇö big rock pourovers just under the surfaceÔÇöand you know they are backed by terminal hydraulics. Rooster tails jet up from pin rocks like sawdust off a rotary blade. Patches of bubbling slackwater swirl out of the havoc, and the eddy lines can catch and flip a boat in an instant. You see the horizon lines of ledges, edged against a plummeting background. Then you drop into the trough and you’re buried by a surging wave, and the freezing water takes your breath away as the current sweeps you toward the next drop.

Few other sports require the processing of so much data so fast. Survival depends on split-second decisions, both reflexive and deliberateÔÇöand not just one or two in a drop, but continuously, in a dynamic flow of constant recalibration. One mistake in the thousands of moves in a single dayÔÇögoing a foot too far to the left, or getting thumped off line at the wrong momentÔÇöand your life may end.

For all these reasons, kayaking is a game for individualists. It attracts adventurers who revel in going it alone. Each of the men on the Tsangpo team had notched some of the wildest waterfalls and drops in the history of the sport; many times they’d each been the only member of a group willing to give it a try.

For Lindgren, leadership on the Tsangpo required striking an exquisite balance. He needed the courage and unblinking confidence of his companions; he also needed them to embrace the real humility that the river demanded and to put aside their personal desires without hesitation. And he had to maintain this focus while bearing the ultimate responsibility for every problem, trivial and large, and every life on the expedition. His first big test came on the fifth day, near the same rapids that had killed Doug Gordon.

So far, the river had been a mixture of easy passages, steep rapids, and what Lindgren described as “insanely steep” boulder gardens. “Quality whitewater,” Willie Kern called it. The rapids and flatwater stretches took the kayakers past logging camps, terraced fields, occasional clusters of stone houses, and Buddhist shrines.

By dawn on day four, signs of human habitation had disappeared. The flat river was the color of turquoise, polished hard and cold in the early light. On all sides the walls of the gorge soared thousands of feet, spuming mist. Just downstream, a forested mountain rose off the river, layered in cloud like a Tang Dynasty landscape. Beside it, a glacier churned down a side canyon, shoving a jumble of rock and earth before it. In the damp sand the tracks of a big catÔÇöpossibly a leopardÔÇöand her cub traced along the water’s edge. We had passed beyond Musi La, a spur that juts 2,300 feet above the river, the great barrier to hunters or pilgrims from upstream. It was brutally steep. Gnarled rhododendron thick as a man’s thigh, bamboo groves too dense to walk through, and towering hemlocks eight feet across had confounded even the Sherpas, and the porters were not happy. On the other side, the route lost all semblance of a trail.

On the river, the paddlers immediately confronted a steep drop. Six of them picked up their kayaks and portaged, but Steve Fisher, the South African, scrambled up to a boulder where I stood watching. With the air of a master golfer lining up a 30-foot putt, he outlined the exploding current. “No worries,” he said.

Fisher hiked back to his boat and pushed off, seal-launching down a granite slab into the water. He charged into a strong current that ran through a maze of boulders along the left bank, threaded two narrow chutes, caught a micro-eddy, and climbed out on a little island of rock. He stood holding his paddle and scouted again, then got back in and, with two powerful strokes, found the thread of current he wanted for his flight over a ten-foot fall. Disappearing in the froth below, he took a few heart-stopping moments too many to pull clear, then paddled hard on a stormy ramp of water that drove him into a surging eddy along the left wall. He flipped and rolled upright, his boat bobbing and scraping the wet black rock.

There is no more terrible place to roll and recover than in a fierce eddy against a wall, but Fisher kept his focus. Urgently scanning for a way out, he set his angle and poured on a sprint, breaking out of the vortex and into the main current, where he dodged a crashing foam pile, broke through a big wave, and was clear.

If a whitewater kayaker is unable to paddle out of danger, he has only one option: pull the cord on his spray skirt, slide out of the cockpit, and swim for safety. In the drastic rapids of the Tsangpo, however, there would be little chance for a team member in a kayak to rescue a paddler who was out of his boat. A throw rope could make it only a fraction of the way across the river. Despite the moral support of running in a group, each kayaker was essentially on his own.

The equation was simple: A swim meant almost certain death. And so the team had made a grim pact. “We talked about it.” said Johnnie Kern. “We decided that out here, you drown in your boat. Swimming’s not an option.”

FOR THE OTHER PADDLERS watching Fisher’s run, especially Lindgren, it was a decisive moment. Fisher had cowboyed down and made itÔÇöbut he might not have. Communication hadn’t been clear among the paddlers; there had been no plan of attack.

Lindgren leads with unrelieved and charmless intensity. For most of the trip he’d been wound tight as piano wire, worrying, calculating, keeping his own thoughts and company. At times he was preoccupied, surly. When someone said good morning, he often didn’t reply, or shook himself out of his abstracted state long enough to respond with an automatic, “Yeah, good morning, how’s it going?” His friends, the paddlers who had known him for years, said it was just his way on an expedition. You got used to it.

“At first I thought he was rude as hell,” Johnnie Kern said. “Then you learn that’s Scotty.” Lindgren’s management style put everyone on guard, and he wanted it that way.

Like alpine climbers, extreme kayakers have to reckon not only with their own risks, but with the guilt and grief that come with the loss of close companions. In 1997, Johnnie and Willie Kern lost their older brother Chuck on the Black Canyon of the Gunnison in ColoradoÔÇöthey watched him miss his line and disappear into a horrendous boulder sieve. Lindgren drove nonstop from California to help the twins recover the body. “Chuck was my best friend,” Lindgren told me one night in Lhasa. “I’ve lost 11 friends in three years to rivers.”

Not long after Fisher’s close call, the Tsangpo kayakers reached the stretch of river where Doug Gordon had died. They pulled off the water and, with the torrent reverberating in the narrow inner canyon, observed a moment of silence in honor of a fallen colleague.

No one on the team is willing to say much about it, but that day the kayakers also held a meeting that changed the rules of engagement. One expedition member later told me that “Steve got a bit of the stick.” But the real point of the meeting was that a solo run like Fisher’s wouldn’t happen again. The paddlers vowed to forgo wild-hare impulsiveness and to work as a team. That meant moving slowly, methodically, and communicating constantly. No more winging it.

For the next two days they paddled nearly continuous whitewater, with the river making its inexorably steep drop through the HimalayasÔÇöa flow of 15,000 cubic feet per second down gradients of 100 to 150 feet per mile, a volume equivalent to the Colorado River as it pours through the Grand Canyon, but about 15 times steeper. On the eighth day on the Upper Tsangpo, a black pyramid of rock and pines loomed up ahead on the left. The mountain vented steam, and you could smell the sulfur. This was the fortress of Dorje Traktsen, one of the abodes of the vengeful protector deity of the gorge. Across the river on a wooded bluff lay the stone ruins of the ancient monastery of Pemak├Âchung. All around it was flattened vegetation: the beds of animals called takinÔÇöstout, low-slung bovines that are a favorite prey of the region’s hunters. Gorals, goatlike creatures with ruddy coats, grazed on the hillsides. Downstream, the river disappeared between soaring walls, twisting through layer after layer of steep spurs and drainages cutting in from either side, marching eastward into a distant haze. Beyond the gorge, high mountains of snow and ice formed a rugged white backdrop. Farther still, visible through a notch, was a piece of the snowy Pome Range, walling off the north side of the Lower Gorge and forcing the Tsangpo to run south to India.

On the tenth day the kayakers reached a section of stepping drops that they couldn’t see down. Fisher, Abbott, and Knapp scouted downstream on foot, reporting appalling holes and a must-make ferry across the river. (During a ferry, a kayaker points his bow upstream and uses the current to move sideways from one side of the river to another.) If you miss a must-make ferry, you get swept downstream into features that have a high likelihood of killing you.

Lindgren nailed the ferry first, with Willie Kern and Ellard following. They shot across the river, aiming for the lower edge of a boulder, behind which lay a pool and safety. But curling off this rock was a big pulsing wave that fed like a funnel into the main current. When Johnnie Kern hit the wave, it surged and tossed him upside-down into the middle of the river. He was running blind toward treacherous ledges, with his brother screaming at him to stay in the center. Heeding the warnings, he found an escape line and eddied out.

It wasn’t over yet. Exiting the sanctuary, Fisher slammed into a big wave train, augered into a hole, flipped, rolled, and came up holding the two pieces of his broken paddle. As he careened into another huge hole, he used half of his paddle, digging like a possessed canoer and fighting his way across the river.

“I knew how Doug Gordon might have felt,” Fisher said that night, “getting swept helplessly to the center of this huge river, not knowing what was below, knowing how big it all is.”

DAY 11, FEBRUARY 13, TIBETAN NEW YEAR. The porters refused to work. They were growing more weary and rancorous by the day; there had been a series of petty theftsÔÇöwatches, river knives. A few hundred yards below camp the Tsangpo jogged left and ran northeast, straight through a corridor of high vertical cliffs with no bank. Lindgren dubbed it the Northeast Straightaway. The team expected to find the heaviest whitewater yet, and they needed a day to scout it.

The Straightaway was relentless. In places the current was so loud that they had to yell into the handheld radios to be heard by the ground crew. More than a third of the water was unrunnable, so the team spent hours hauling their kayaks from boulder to boulder, picking their way along cliffs and relaunching through caves and off high rocks.

When it was all over they skated across a green pool and into a beautiful camp, a deep cove of beach, jumbled with rocks and driftwood. Pines and hemlocks leaned over from the opposite wall; overhead was a swath of sky as blue and clear as the midwinter Himalayas could offer.

The team was exhausted and euphoric. Willie and Johnnie Kern unzipped their drysuits. “Big day,” Willie said, beaming. “Good day. That’s what we live for, right there.” Johnnie gave up a hint of Yankee smile. “Proud,” he said. “It was proud. Running, portaging, scouting, running. Proud.” He stood at attention for a second and broke into a grin.

Two short days and a few tough rapids later, on February 16, the seven kayakers hit small shore eddies at a drainage above a tight left corner: Clear Creek. The corner was hemmed by a cliff and ravine that climbed 5,000 feet straight up into a world of Himalayan snow. They threw their paddles onto the pale boulders, stepped out of their boats, and celebrated the historic moment. The ground crew cheered. In 14 days of combat they had completed the 44 miles of the Upper Tsangpo Gorge, paddling 100 percent of the runnable water and portaging only 23 times. Lindgren pulled the Explorers Club flag out of his boat and unfurled it. “The Upper Tsangpo Gorge is officially stamped,” he said.

Nobody basked in the glory. All Lindgren’s team had to do was look around: a dead end surrounded by high rock walls and thousands of feet of near-vertical mountain face. The river disappeared around the corner with a sound like jet engines. Just below, it cascaded over Rainbow Falls and then, a few hundred yards later, the cataract of Hidden Falls. Between Hidden and the confluence with the Po Tsangpo was the so-called Five-Mile Gap, a stretch of the Tsangpo so deeply incised that it had been seen by few, if any, Western eyes. The only way out was up.

UP 2,000 FEET INTO THE SNOW, and then another 3,000 feet over a pass that in winter was a complete mystery. This was the way to the Lower Gorge, where Lindgren was determined to lead his kayakers to another historic first descent.

That evening, in a narrow woods camp, Dustin Knapp stripped the shoulder straps and hipbelts off his backpack and worked with intense concentration to attach them to his kayak. Soon the other paddlers were retrofitting their boats for the mountain portage.

At daybreak the Tibetan porters shouldered their loads and followed the five Sherpas into the woods. The kayakers stood their boats on their bows, slipped into and buckled their pack straps, and tipped their awkward loads free of the ground.

The ancient trail went straight up through dense jungle, over rock slabs and a dirt embankment with chips of rocks and roots for handholds. It wound higher and higher, etched in thin footholds of dirt and root, under spruce and pine, and crested out on a jagged, rocky spine just below the tree line. The kayakers moved along the ridge like colorful mountain beasts, passing an old prayer flag, refined to near-transparency by the wind and sun. After nine brutal hours, the long train of porters, kayakers, and trekkers trudged onto a snowfield and climbed through an avalanche run-out to make camp in a bowl of snow at 9,200 feet.

At first light the next morning, Andrew Sheppard led the way, slowly, steadily cutting steps up a steep couloir. His ice ax made a rhythmic double cut and scrape, followed by the sound of his heavy boots kicking out the footholds. Jangbu Sherpa swung his ax behind Sheppard to deepen the steps, with the other Sherpas right behind. Then came the ragged line of porters and the seven red and orange and yellow kayaks.

The line had moved out of the gully, tenuously ascending a steep, open face when the trance was broken by a loud cry: “Flip over! Flip! FLIP!” Tsawong, a Tibetan translator from Lhasa, had slipped and was skidding down the mountain. As he sailed past the long string of men, the call went up for him to flip onto his stomach and self-arrest. Near the precipice, he somehow did, using his trekking pole. He lay for a minute in a little heap and cried.

In the bright sun the snow was softening dangerously, but there was no time to rope up. A porter knocked loose a plate-size chunk of rock, which glanced off Johnnie Kern’s forearm and hurtled between Ken Storm’s legs, skimming his calf and almost knocking him off his feet. Finally the porters and kayakers crested the top. On a windswept hump of rocks surrounded by a sea of endless snow and thrusting peaks, they dropped their loads at 12,400 feet.

Lindgren slumped in the cockpit of his yellow kayak with his chin on his hands. “That was fucked,” he said. “That was not safe. Not in the least bit.”

Now we had to traverse. Senchen La, the pass over to the village of Pay┼Ş which sat below the great confluence, demanded that we contour north along the top of the ridge before dropping over. There were cliffs and icy gullies, and it would probably be as steep or steeper than what we had just completed.

The porters refused to take the route. They crowded, bareheaded and windburned, onto a rocky promontory, with the eastern Himalayas spilling brightly all around them, and told Dave Allardice they were not, no way, going over Senchen La. They lit cigarettes and told him where we were going instead: the village of Luku. No dicey traverse, just straight over the top.

Allardice is a tough customer. When Nepalese Maoist guerrillas recently showed up at his Kathmandu-based outfitting company demanding tribute, he sat them down and told them how much he had already done for local schools and villages, and that he wasn’t going to give them a bloody penny. They gave him a cigarette and he concluded with a lecture on the political realities of Nepal.

Now he gave his orders. This time, the porters shook their heads. Senchen La was too dangerous, impossible in winter. We go to Luku first, they said, then upriver to Pay┼Ş. Dave demanded, then reasoned, then cajoled, and then finally decided that maybe the porters had a point.

The expedition poured over Luku La into a snow drainage and glissaded down for miles. Mike Abbott grabbed the cockpit of his boat with one hand, put his other out as an outrigger, and let the galloping kayak pull him down. Jangbu, Sheppard, and the porters slid on their butts. After one more traverse onto rock above a plummeting icefall, we were in the woods again, and it was dusk.

Willie Kern was shakenÔÇöeveryone was. “I just put myself at greater risk than I ever allow myself on the river,” he said.

“I was climbing steep snow, in little footholds, strapped into a perfect toboggan,” Dustin Knapp said.

Steve Fisher, the survivor of a thousand close calls, said flatly, “That was the most dangerous thing I’ve ever done.”

EIGHTEEN DAYS AFTER THE PUT-IN at Pe, and after four days of non-stop portaging, the exhausted company straggled out of the jungle of the Lower Gorge and into the village of Gogden, population about 150. Beyond the village lay the Tsangpo, in a riven chasm too deep to show its waters, and across the gorge was a sloping wall of terraced fields and scattered houses beneath snowy peaks.

The expedition members were invited into several houses, and in the dimness of smoke-blackened rooms with wide-plank floors everyone ate fresh popcorn and drank bowl after bowl of clarified grain liquor sloshed out of plastic gas cans. The open hearths glowed red, the bronze prayer wheels beside them gleamed, and the rafters were hung with pig stomachs packed with yak butter. The kayakers mimed to their baffled M├Ânpa hosts. Unlike the farmers of Pe and the Upper Gorge, the M├Ânpa are huntersÔÇöone of the few Buddhist hunting cultures on earth. They served yak-butter tea to cut the liquor, and by the time we were led into a sloping cow pasture to set up camp, some of us couldn’t untie our shoes.

The next day Mike Abbott, Willie Kern, and Dustin Knapp hiked down into the Lower Gorge to take stock of the river and returned to report a startling transformation: the turquoise current, swelled by the water of the Po Tsangpo, flowed through a 300-foot-high bedrock scour on either side. The rocky banks we’d seen in the satellite photographs were gone. The river was now a barren trough of steep walls lined with a stupefying scar, the track of a cataclysm. In June 2000, only a month after Space Imaging’s satellite had passed overhead, a great mud dam that had been formed by a landslide on the Yigong, a tributary of the Po Tsangpo, had burst. Ken Storm and the team had heard rumors about this flash flood, but nothing had given them an inkling of the scale of transformation on the Lower Gorge.

The team received another unwelcome surprise when the Gogden elders informed Lindgren that the expedition was subject to an ancient Tibetan tradition known as ula. Under the rule, they said, traveling parties are obliged to change porters at every village. They politely said they wouldn’t let the expedition move until Lindgren and Allardice relented, but there was a steely threat of physical intimidation behind the ultimatum. The porters from Pe, though, figured they had been contracted to accompany the expedition all the way through to the end of the trip and were expecting to be paid in full regardless.

There was an afternoon of meetings at one end of a pasture, some of the head porters sitting in a tight circle in feverish negotiations with Allardice and Lindgren. Finally the younger porters got impatient, pushed aside the elders, and demanded to be paid right away.

Allardice said, “Police,” and made a handcuff motion. Dustin Lindgren pointed at faces and gestured as if to write down their names. Furious shouts went up. When translator Tsawong took out his porter book to look up the names of ringleaders, the hotheads lost it and the whole crowd surged forward. Punches flew, and everybody was yelling. The porters, most of them armed with knives and machetes, had become a mob.

Desperate to head off disaster, Lindgren got on the satellite phone and called the Chinese liaison who had obtained our permits and arranged our overland travel. “Our lives are in danger here,” he said. “They’re threatening our lives.” He asked the liaison to speak to one of the headmen from Pe, and the two talked for quite a while, with the phone cutting out several times.

It was a low point for Lindgren. The portage had taken its toll, he was exhausted, he’d lost weight. Now this.

Allardice was measured. “Scott, is it worth it, keeping up this talking?”

Lindgren made the decision. “Right now, we have no option except to pay them what they want,” he said.

So he paid, $9,000 more than the original bargain. With a bitter taste he hired 38 new porters from Gogden, and the expedition moved on.

EVERY EXPEDITION KAYAKER has the same nightmare: paddling to a point of no exit. A river with no shoreline is a one-way street. Once walled in, with only death drops below, there is no way out or back. At high flows, a river like this exhibits a unique and deadly hydrology. Water deflects off the walls and piles on top of other water, creating a gradient toward the center of the channel as well as downstream. So a kayaker trying to get to one side has to actually paddle upstream. Shore eddies become surging boils of water that can dome up and reject a boater just as he tries to break in.

The lower Tsangpo had become such a river. The flood had simply erased the rocky bank that had been the paddlers’ margin of safe conduct in the Upper Gorge, leaving behind only scoured bedrock. As we hiked out of Gogden, the river revealed itself now and then, thrashing wildly against the gouged wallsÔÇöwith no takeouts in sight. It began to dawn on the paddlers that the Lower Gorge had almost certainly become unrunnable.

Over another snowy pass and down into tropical forest, to a cluster of houses on the lip of the gorge: the village of Pay┼Ş. From here we could look straight up the river, S-turning through sheer jungled walls and slides thousands of feet high. At every bend were thundering river-wide features, waterfalls, and ledges, all hemmed in by a 30-stories-high band of bedrock. Lindgren shook his head. “Pay┼Ş to Luku is out of the question. We’ll take a look upstream.” The paddlers scouted. They spent a day in two teams, one dropping to the river straight below Pay┼Ş, the other hiking upstream through the S-turn to look for river access and scouting possibilities. It didn’t look good.

Meanwhile, despite the volume of snow we’d encountered up high, Storm, Allardice, Sheppard, Dustin Lindgren, two Sherpas, and two Tibetan guides decided to take their chances on an audacious side-expedition: They’d try to climb over Senchen La and drop to Hidden Falls. While the rest of the expedition continued upstream toward the top of the Great Bend, this small party headed straight up the side of the gorge. They said they’d be perhaps five days behind the rest. For the first time, the team was splitting up.

Lindgren still hoped that at least a piece of river below the confluence of the Po Tsangpo could be tackled by the kayakers. After another reconnaissance, Lindgren’s group at last came back down to the Tsangpo and camped on a smooth beach of fine white sand tucked among huge boulders. The river rushed and heaved by.

“It’s a different river,” Lindgren said, “pretty big.”

A run from the confluence to Pay┼Ş was only about eight river miles, but Fisher guessed the flow tearing past here was 25,000 cubic feet per second, almost twice the current of the Upper Gorge. There were big drops just downstream, with no likely place to pull out and portage. The satellite maps were now useless for gauging rapids and planning a route.

At our final camp, in the village of Tsachu, perched high on a ridge above the river, the seven paddlers conferred. Lindgren said, “As far as I’m concerned we’re all wearing gold medals right now.” He asked the paddlers for a show of hands: Who was willing to call it quits? Seven arms went up.

The river had asserted itself. It had radically changed, and it humbled the paddlers. Lindgren had made it clear from the start that they’d take no blind chances. They’d gotten this far, and he wasn’t going to leave behind any dead.

They’d been the first to descend the Tsangpo’s great prizeÔÇöthe fabled Upper Gorge. Now they brought the expedition to a close with a first descent of a nine-mile section of the Po Tsangpo. Then they paddled through the confluence and down the Yarlung Tsangpo a few miles, around the apex of the Great Bend. The next day the Hidden Falls crew arrived in camp, triumphant. They had reached the falls and Andrew Sheppard had rappelled right to the brink, to a point where no one had ever stood. Then, like the radical mountain man that he is, he had free-climbed to the very edge of Rainbow Falls.

We stayed a week in Tsachu. Flocks of dark cranes were migrating northward, and at night their frayed, disembodied cries fell out of the dark. Curious villagers gathered at our camp and told us that something unutterably sad was soon to unfold in Tsachu and Pay┼Ş and all the other hamlets around the Great Bend. The Chinese-controlled government had told them that in the spring these ancient villages would be depopulated, that the residents would be relocated to new towns and farmland outside the gorge. There were rumors of a national parkÔÇöor a huge hydroelectric project.

No one will live here anymore? we asked. They shook their heads.

We hiked out of the Po Tsangpo to the Lhasa-Chengdu highway. It felt like the end of more than just an expedition. If the news was true, M├Ânpa hunters would no longer haunt the high trails, replenishing prayer flags as they went. There would be only the cries of cranes flying over, and the wind, and the unceasing sound of the great river. The wind would whip the white flags and take their inked prayers, little by little, into the gorge, until they were washed clean.