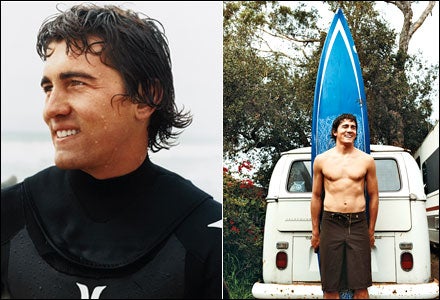

Greg Long has stopped again, waiting for me to catch up. It’s late February, and the lean, tousle-haired surfer is jogging in place on the beach at Trestles, the world-famous break where he grew up, an hour south of Los Angeles. He’s wearing a hooded wetsuit, carrying a pair of swim goggles, and indulging himself in a bit of schadenfreude as he flogs me up the beach. I’m spent, and we’re less than an hour into his daily regimen. So far, we’ve sprinted four miles in soft sand and returned swimming along the shoreline, while overhead waves crashed on top of us. His goal, he tells me, is to simulate the violence of a big-wave beatdown. When I finally catch up, he’s laughing.

“Are you all right?” he asks.

I nod.

“Want me to hang with you?”

“No,” I cough. “Do your thing.”

Long’s thing is a relentless, year-round quest to find and ride the planet’s biggest waves. And, at 25, he’s extremely good at it. In January, at Cortes Bank, an open-ocean break 105 miles west of San Diego, he and his tow-in-surfing crew caught what were likely the tallest waves ever ridden: at least 80 feet. A week later, just south of San Francisco, Long won the iconic Maverick’s Surf Contest by paddling into 20-foot barrels. He’s had his board chomped from beneath him by a ten-foot tiger shark off Oahu and been held underwater for several minutes while multiple waves pummeled him. And after the winter swells go quiet in the Pacific, he switches hemispheres. In July 2006, at Dungeons, in South Africa, he rode a 65-footer and collected the 2007 Billabong XXL Biggest Wave award, along with $15,000 that he split with his jet-ski driver.

That’s a decent paycheck, until you compare it with the millions that World Tour surfers like Kelly Slater and the Irons brothers make. Big-wave surfers operate under the radar, eschewing serious money for lifestyle. There is, of course, an exception: 44-year-old Laird Hamilton. Yet Long’s recent dominance has been so complete that even his status seems within reach.

But while Hamilton got rich and famous by ignoring all contests and instead having his picture taken towing into monster waves, Long is sponsorless. “They’re on different planets,” says Evan Slater, the editor of Surfing magazine. “Laird is a superhero. Greg is a classic surfer—understated and personable. But he could be the undisputed king of big waves.”

First, Long needs a job. From 2001 to 2006, he made a modest five-figure salary as a team rider for Ocean Pacific. But when OP was sold in November 2006, the new bosses dumped their sponsorship program—and Long with it.

So he’s still living at home with his parents. Long’s father, Steve, is a lifeguard at San Onofre State Beach—where Trestles is located—a job that comes with coveted employee housing. It’s where Greg and his brother, Rusty, also a well-known big-wave rider, were raised.

Since OP dropped him, Long’s had to fund his big-wave missions with savings and contest winnings. He even buys and barters for his own boards, including the nine-foot-six Chris Christenson he used at Maverick’s. And yet, before the last heat, the six finalists agreed to split the prize money evenly. “As far as I’m concerned, that $30,000 was the devil sitting in the lineup,” says Long.

It’s not that he’s radically anticapitalist. Long just thinks surfers should be intrinsically motivated. Take, for example, the Cortes mission: While the rest of California suffered a storm that knocked down trees, cut off electricity, and closed roads, Long, Brad Gerlach, Grant Baker, Mike Parsons, and Rob Brown braved 20-foot swells on the hundred-mile journey out to sea. With room for only one of the team’s two jet skis on board the expedition’s 36-foot catamaran, Long took turns driving the other ski all the way to the bank.

“It probably wasn’t the safest thing,” he says. “But if somebody else had caught those waves, I’d have cried.”

Two days ago, Long packed up his gear at the end of the North Pacific’s big-wave season. “The jet stream’s split,” he told me as I helped him wheel his jet skis under an awning at his parents’ house. Greg wasn’t the only Long packing up. After 33 years as a lifeguard, his dad has retired and is moving to Oregon.

“This is a new chapter for me,” says Greg. “When I come home next fall, I’ll probably be living in my van until I can find a new place to stay.” Or not. In April, he was close to signing a lucrative multi-year deal with Hurley.

“I thought about going back to school and calling it quits,” says Long. “Then there’s the side of me that says, ‘Go chase every big swell you can, and have the time of your life. It’s going to come around.’ ”