Excerpted from , by James Nestor. The full ebook single is available from .

More Atavist Originals

Half-Safe.

Half-Safe.THEY HAD SPENT 14 days in darkness.

Late on the morning of the 15th day, December 2, 1950, light finally peeked through a crack in the curtain that hung over the passenger-side window. Ben lifted the curtain and looked outside. The sky was blue, and the sun, as big as a dinner plate, shone brightly. The storm clouds had retreated to the horizon. Ben took a dirty tissue from his shirt pocket, swabbed his eyes, and lifted himself from behind the steering wheel.

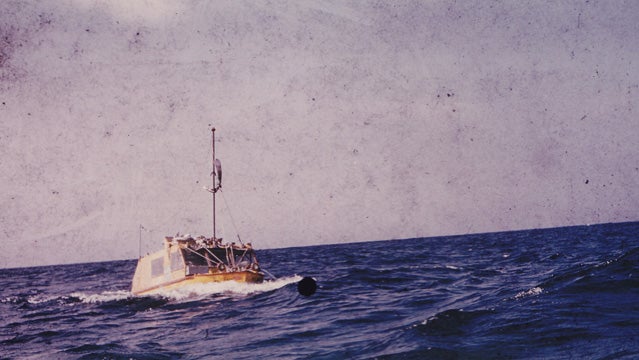

It had been four full months since Ben and his wife, Elinore, steered the tiny amphibious jeep they called Half-Safe into the frigid waters of Halifax Harbor and headed east toward Africa. It was the first time anyone had tried to circumnavigate the world by land and sea in a single vehicle, let alone one that was eight times smaller than any motorized boat that had ever crossed the Atlantic. It was a harebrained scheme, and the Carlins knew it. That was the point.

���ϳԹ��� for its own sake had first attracted Ben, an engineer from rural Western Australia, to Elinore, an American Red Cross nurse, when the two met in India at the end of World War II. And there could be no more outlandish adventure than an attempt to “drive” across the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans—and actually drive across the continents in between—in an automobile. Especially this automobile—a converted 1942 GPW (General Purpose Willys) amphibious jeep built by Ford for the U.S. Army. It looked like a cross between a 4×4 and a rowboat, with a stubby pointed front, a square rear end, and a five-by-10 steel box on top. It was half car, half boat, and entirely ridiculous. The GPW amphibious jeeps were designed to putter through shallow streams for a few minutes at a time and usually failed even at that; they had proved so useless in the field that the Army canceled production. They were never intended to be used on the ocean.

Helpless and lost in the middle of 41 million square miles of open water, Ben and Elinore realized that their comic little adventure was quickly becoming a suicide mission. Both were in their thirties, but looked as though they had aged decades in just a few weeks. Elinore, famished and vomiting anchovies into a tin mug, had gone from voluptuous to skeletal. Ben looked worse. His skin was pale, a delta of stress lines spread across his forehead, and his eyes were baggy and bloodshot. His face was caked with exhaust soot, engine grease, and sweat.

But now, weeks into their Atlantic crossing, the Carlins had no choice but to suck it up and keep following the compass east, toward the coast of the Spanish colony of Western Sahara, toward solid ground and safety.

Ben squinted out Half-Safe’s back hatch and looked at the deck. The jeep was sitting dangerously low in the water. Waves washed over the windshield and side windows, threatening to swamp the cabin. The cloth sea anchor, designed to drag in the water to stabilize the vehicle, floated behind Half-Safe in tatters, shredded by the storm.

I FIRST HEARD ABOUT Carlin and Half-Safe about a decade ago, after my own, less extraordinary misadventure at sea. I was sailing the Golden Gate, the strait spanned by the famous bridge, outside San Francisco with an old friend named Steve, a novice sailor who had just bought a 36-foot boat. We were barely out of the harbor before it became obvious that neither of us knew what we were doing. Then the motor broke. Soon we were drifting slowly west, toward the open ocean.

It was my first real taste of being adrift at sea, lost. For six hours, Steve and I felt alternately terrified and oddly bored. By nightfall, Steve had given up and called emergency rescue. As we waited to be towed back into the harbor, he told me about a guy named Ben Carlin who spent years in this kind of predicament—years stuck in the five-by-10 cabin of a tricked-out military jeep that was somehow also a boat, trying to make it around the world.

When I got home, I went online and read what I could. The Ben Carlin story seemed too ridiculous to be true—but if it was true, it was the most bizarre adventure tale I’d ever heard. Either way, I had to find out more. There wasn’t much to find, however: a one-line mention on a GeoCities page, a picture of the jeep on a site maintained by Army-vehicle enthusiasts. Carlin had written two books offering partial accounts of the journey, but they were both long out of print and difficult to track down.

Ten years after first hearing about Carlin, and still unable to piece his story together, I flew to Perth, Australia in November 2011. If there were answers to the Ben Carlin mystery they’d be at the Guildford Grammar School, his former alma matter, which houses nearly all of the surviving records of Carlin’s bizarre around-the-world quest. A few days after arriving at Guildford, Carlin’s life and his adventure began to unravel in ways more strange, tragic, and extraordinary than I had ever expected. Soon, I was no longer just exhuming Ben Carlin’s story after 60 years, but in an odd way becoming a part of it.

BY THE MORNING OF December 2, 1950, the rain returned, followed by wind and waves. By afternoon, the swells had risen to 30, 40, even 50 feet. The jeep was flung stories-high over the crests of the waves and down the other side so violently that Ben and Elinore were shot from their seats into mid-air. The tank carrying most of Half-Safe’s fuel broke loose from the hull; Ben watched as it bobbed in the spindrift and then disappeared into the darkness. He had no other option but to gun the engine and try to run before the storm. This was no ordinary storm. It was a full-on hurricane—and the Carlins were in the middle of it.

By evening the swells had gotten bigger. They slammed into the jeep with such deafening force Ben knew it was only a matter of time before the roof collapsed, the cabin flooded, and the jeep sank. Ben turned to Elinore and made her scream the escape procedure in his ear.

“You shout, ‼��ܳ�,’�ĝ she yelled, her voice straining above the din of the rain and wind beating on the steel walls of the cabin. “I get out and wait. You follow and grab the gear. I follow you. Keep in contact!”

Another wave hit.Ben pulled the lighter from his shirt pocket and lit a cigarette. Elinore watched the cherry dance in the darkness, wondering which of the waves detonating against Half-Safe’s windshield would be the one to finally burst in. Through the passenger-side curtain, she and Ben watched the sky darken. They felt a swell below their feet inflate like a giant lung and crash down the other side. Ben tumbled, his cigarette arcing across the dashboard like a rescue flare shot into a moonless night. The window went black. Half-Safe climbed another wave.