The Greatest Boat Race Ever (Dreamed Up Over Beers)

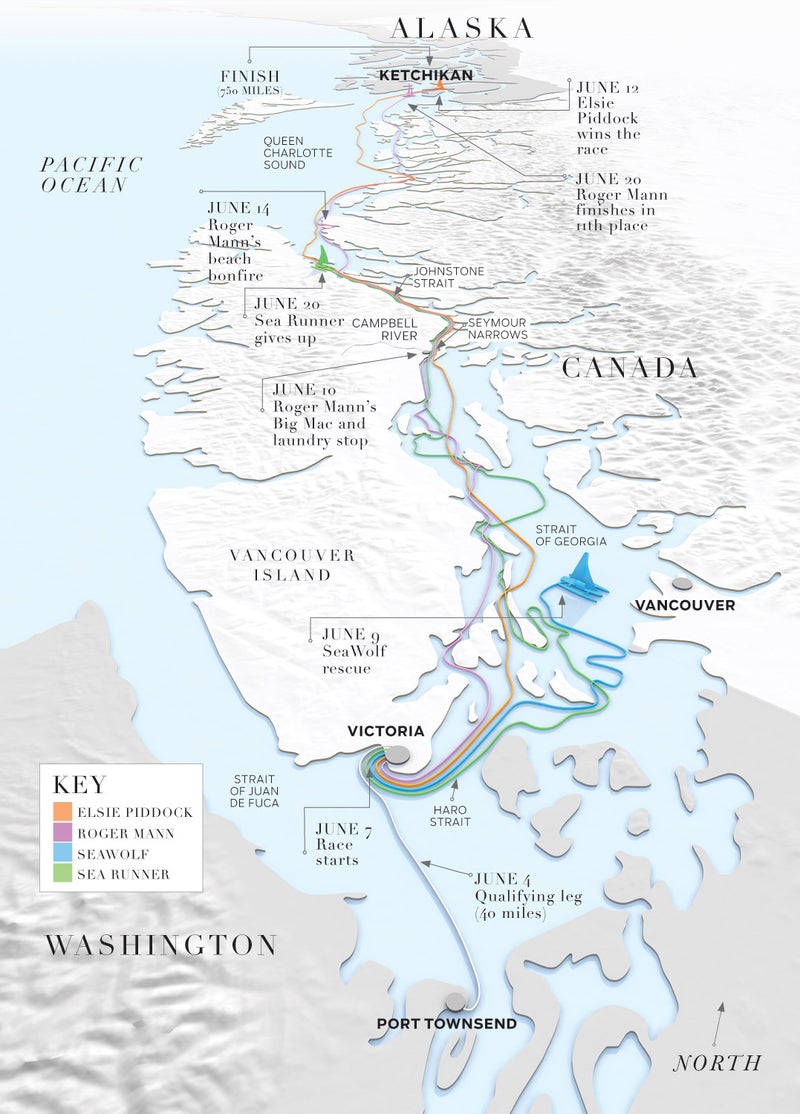

The rules: Pilot a boat 750 miles from Port Townsend, Washington, to Ketchikan, Alaska—no motors allowed. The prize: $10,000 nailed to a piece of wood. The result: Seven capsizings, four lifesaving Big Macs, one dramatic coast guard rescue, and a cast of oddball adventurers who reclaimed the salty heart of ocean racing.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On a concrete ramp near the pier in Port Townsend, Washington, Alan Hartman pulls on his eye patch. It’s uncomfortable, but the doctors say it’s necessary to keep salt water out of his right cornea, which the 47-year-old fisherman recently speared while chainsawing brush near his remote Alaska cabin.

He drove himself an hour to the nearest hospital, where he encouraged doctors to cut out the eye so he could make it into a necklace, but ten stitches saved his sight. Hartman hauls his boat, a 18-foot trimaran, down to the beach and squeezes his rain-barrel torso into the two-foot-wide cockpit. He dips a paddle into Port Townsend Bay and raises a flimsy sail. His tent and sleeping bag are strapped to the hull without any weather protection. He is resolute that neither his wound nor some wet nights’ sleep will keep him from the journey ahead. “This race is going to change my life,” he says.

It’s 4:30 a.m. on June 4. The predawn light slowly turns the sky from charcoal to slate, revealing clouds on the water and a total of 53 vessels making final preparations for today’s 40-mile crossing of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the first leg of a 750-mile quest that will conclude in Ketchikan, Alaska.

The teams have 36 hours to reach Victoria, British Columbia. Those who make the cut-off will continue racing up the coast. The boats that take too long or require assistance will be disqualified. There are small boats, big boats, strange boats, solo racers, and crews of up to six men and women, all competing under a chosen team name. Six Canadian rowers are Team Soggy Beavers. Alan Hartman opts for the more literal Team Hartman. Three sailors on a lightweight carbon-fiber trimaran call themselves Team Elsie Piddock, after a children’s-book character. The name may be tame, but the crew is not: their captain is Al Hughes, a Seattle sailor with immense hands who lives on a boat and has completed three solo races across the Pacific. He stands aboard his vessel in a drysuit, sizing up the field. Looking around, he is amazed at the motley fleet assembled.

Of some concern to Hughes is a shining 22-foot catamaran emblazoned with the Stars and Stripes and the Sperry Topsider logo. It’s crewed by Team FreeBurd: Tripp and Chris Burd, 31- and 27-year-old -brothers who live in the sailing mecca of Newport, Rhode Island, and look like they just stepped out of an Abercrombie ad. Tripp, who has swept-back blond hair and a square jaw, has predicted that they will complete the opening leg “by breakfast.”

Nearby, George Corbett and Mike McCormack, thirtysomething buddies from Squamish, British Columbia, are futzing with their neon yellow 17-foot trimaran. Corbett, a thin engineer with a crew cut, and McCormack, a long-haired sailing guide, found it on a beach in Mexico, full of sand, after a hurricane. It’s a foiling boat, like the ones used in the most recent America’s Cup, meaning that when it catches enough wind, a submerged hydrofoil elevates the hulls out of the water, reducing drag and radically increasing speed. This one, however, is rather spindly and not intended for open-water odysseys. Looking at it, Al Hughes is dubious about its chances. But the guys are bullish. They have dubbed themselves Team SeaWolf, after the legendary predator that feeds on salmon up the British Columbia coast.

About 20 yards down the beach, a small crowd hovers around another 17-foot catamaran that looks as though it was inspired by the Millennium Falcon. The hulls are made from recycled plywood; the foam inside came from a dumpster. In the cockpit is a pedal drive assembled from old bike parts. The tiller is made of bamboo purchased on Craigslist and lashed together with bike tubes. On the bow sits a piece of amber of the sort that Vikings used to take to war. The creators of the vessel are two boat-building aficionados from Seattle: Thomas Nielsen, 53, a medical consultant with pipe-cleaner eyebrows, and Scott Veirs, a 45-year-old marine biologist. Calling themselves Team Sea Runner, they are out to prove that money and technology do not always rule the day.

Nielsen and Veirs take a long look at the weather report. It is, in a word, bad. A westerly wind has been blowing at 30 knots all night, forming steep six-foot waves. They decide to swap out their mainsail for a smaller one. This is a delicate matter, because the sails—which are cut into crab-claw shapes inspired by ancient Polynesian vessels—are made of simple tarps, and the mast is constructed from an old windsurfing spar and more bamboo. Veirs, a soft-spoken father of two with calves the size of fire extinguishers, delicately hops on board and says, “This is a good boat to learn to sail on, if you’re in Polynesia.”

Next to them sits a small red Hobie Cat trimaran piloted by Roger Mann, a laconic South Carolina jet mechanic who recently taught himself to sail. He calls himself Team Discovery. He had his boat shipped from a factory directly to Port Townsend; upon opening the boxes, two days ago, he nearly cut off his left index finger, then stitched the digit up himself with his suture kit. He now sits on his boat in a drysuit, calmly eating freeze-dried rice and beef.

The light comes up, and boats push into the bay. At 5 A.M. a foghorn blows. Team FreeBurd tears off in a patriotic blur. Team Elsie Piddock soon catches them. Onshore, someone plays the Soviet national anthem over loudspeakers. Once Team Sea Runner is finally ready, around 6:30, Nielsen puts on a rubber mask adorned with a serpent and starts screaming “Snake face! Snake face!” as he pedals into the maelstrom. Frustrated by limited peripheral vision, Alan Hartman removes his eye patch, baring the pink fury of his cornea. For about 90 minutes, masts of every shape and color hobby-horse over the horizon. Then the first SOS call comes in.

The trailer for the movie , a film by featuring R2AK racers Tripp and Chris Burd of Team FreeBurd.

Welcome to the inaugural Race to Alaska. Billed as “the Iditarod with a chance of drowning,” the race is designed to reclaim the raw, salty heart of ocean competition from the billionaires who dominate technofied events like the America’s Cup. The rules are simple: captain a boat from Port Townsend to Ketchikan along the Inside Passage of British Columbia, with no motors and no support. Don’t get eaten by a bear. The first boat wins $10,000 cash. The runner-up gets a set of steak knives.

Like any good boondoggle, this one was conceived over beer. It was during Port Townsend’s Wooden Boat Festival in September 2013, and Jake Beattie was having a cold one.

Port Townsend is a town of 9,200 at the northeastern corner of the Olympic Peninsula. Residents are a mix of retirees who have realized the American dream and younger people who appear uninterested in doing so. What unites the place is a love for boats. You can’t lower a boom in PT without hitting someone who builds, repairs, or resides on some small wooden vessel.

Beattie, 39, grew up in nearby Bellingham, taught for Outward Bound, and cut his teeth as first mate on the Bounty a decade before it sank in Hurricane Sandy. He was now heading up the Port Townsend–based , a nonprofit that educates people about traditional seafaring.

He was relaxing in a festival beer tent, talking with friends about seizing the proverbial day. In the past five years, wooden boats had enjoyed a popularity surge, a maritime answer to beekeeping and backyard farming. Port Townsend’s Boatbuilding had a wait list, and trade publications like were thriving. This in spite of—or maybe in response to—the age of Instagram and Twitter.

The group started to talk about ocean races. As far as Beattie was concerned, the greatest one happened back in 1968, when Britain’s Sunday Times sponsored the , an around-the-world challenge that attracted every nutjob on water: Nigel Tetley, a South African who sank; Donald Crowhurst, a Brit who’d joined the race to buoy his failing business, then faked his position and disappeared; and Beattie’s hero, Frenchman Bernard Moitissier, who, while leading the fleet, came to the realization that the seas shouldn’t be commercialized and promptly rerouted to Tahiti. Since then? Carbon fiber, GPS, Larry Ellison, the Nascar-ification of sailing.

Beattie took a sip and cracked an expression that he often wears, the half grin of a man who is surprised that the authorities have not yet discovered his most recent prank. His exact words remain a matter of some debate, but this was the gist: “What if we nailed ten grand to a tree in Ketchikan?”

The conversation stopped—and then resumed with a collective hell yes. Despite the spontaneous nature of the proposal, the race route was actually a calculated choice. The Inside Passage to Alaska is a 750-mile labyrinth of open straits, tidal channels, boat-eating shoals, and fast-flowing ocean rivers. It’s often dead calm, perfect for rowboats. Periodically, though, it offers up hellacious headwinds. The tides flow at four, five, sometimes eight knots. Miss an ebb and you might get dragged backward; catch one and you’re in a fast lane full of deadheads, great bundles of water-logged timber that lurk just under the surface. Beattie decided to hold the race in June, when the weather is normally calm but also occasionally not. With good winds, a fast boat would make the trip in a week. With no wind, it could take a month of rowing or pedaling. This would create a nautical Rubik’s Cube, a problem designed to spur the kind of ingenuity that’s gone the way of the sextant.

Now Beattie just needed participants, prize money, and enough cash for incidentals like emergency SPOT satellite trackers, which would connect racers to search and rescue networks and allow fans to follow the competition online. Crowdsourcing was the obvious choice, but Beattie eschewed Facebook and frequently claimed that his cell phone lacked messaging capabilities. Still, he made a to raise $10,000—the prize. The video showed someone nailing cash to a tree and blowing a horn, a siren call to the tribe.

The tribe didn’t immediately beat down the doors. The first registered competitor was Mann, the South Carolina jet mechanic. So Beattie cajoled his friend Colin Angus, a record-setting ocean rower based in Victoria, to sign up, attaching a name to the race. This prompted the Pacific Northwest’s ocean-going set to pay heed, and soon the fleet filled out with ex-Olympians, a septuagenarian former Peace Corps volunteer, veteran ocean rowers, one liver-transplant recipient, two organic farmers, and a midwestern paddleboarder who intended to sleep onshore in his drysuit. A children’s-book author named Hannah Viano signed on after noting the disappointing lack of women in the race, joining a newly engaged couple who work on Antarctic research vessels. Veirs and Nielsen, Team Sea Runner, set upon a rigorous sleep-deprivation training program, as well as hypothermia-endurance sessions in Puget Sound in January. Alan Hartman paid the $650 entry fee in beaver pelts.

Given the fleet’s diversity of experience, Beattie decided to separate the wheat from the chaff in a supported opening leg of the race, the challenging daylong crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria. Competitors would be accompanied by search and rescue teams. After that the safety net would fall away; so, the thinking went, would much of the fleet.

Attrition set in early. Angus, the ringer, failed to secure his boat to his trailer while driving to the race’s start, and it tumbled off somewhere outside Seattle. The organic farmers bailed; something came up. The paddleboarder was concussed by a falling tree in a Missouri suburb. Hartman impaled himself in the eye. He at least stayed in, proclaiming, “I can’t pull a Palin.”

The first SOS turns out to be a red herring—a sailor whose SPOT tracker momentarily turns off, freaking everyone out.

The second comes in at around 8 a.m. and is real. The victims, a duo on a fast catamaran who met just days before the race, have not yet left Port Townsend Bay when their mast crashes down due to a loose turnbuckle. They limp onto a beach, arguing as they drag their boat across kelp beds. The first mate, a kayaking guide, hitchhikes back to town. She will later publicly accuse her captain of a number of charges, including wearing sweatpants during the race (true), towing his boat to the starting line with a Prius (also true), and entering the race under an alias (unverifiable). One down.

Thirty minutes later, a former U.S. Marine in a solo kayak starts taking on water and steadily sinking. A support boat arrives to save him, and another vessel hauls the waterlogged kayak back to Port Townsend.

George Corbett and Mike McCormack of Team SeaWolf are flying along in their foiling boat, making a beeline for Victoria, when their mainsail tears off, forcing McCormack to power them the last seven miles using the craft’s pedal drive. By the time they arrive in Canada, Team FreeBurd has long since finished breakfast.

Meanwhile the half-blind Alaskan endures. For about six hours and 20 miles, Hartman bashes through the choppy waves by paddling, but around 11:30 a.m. the tide shifts and starts flowing south. This, in tandem with the wind, creates big breakers, which repeatedly flood his boat. The first time he capsizes, he doesn’t see it coming. One moment he’s riding a wave, the next he’s in the drink. He wiggles out of his seat and puts all his weight on one of his extended pontoons, righting the ship. His tent and sleeping bag are gone. His primary concern, though, is getting back on board before anyone sees him—aid from a support vessel means instant disqualification. He hops back in and discovers that he has busted his rudder cables. He paddles for Protection Island, a spit of bird-inhabited land at the southern end of the strait, where he strips down and dries off.

A few hours later, he sets back out with no steering. He capsizes for the second time, rights the boat, and makes for a beach. He gathers himself, launches, and capsizes a third time. He limps to shore, calls race command on his radio, and says, matter-of-factly, “It’s beyond my ability and safety zone to continue.” He will spend two weeks in the village of Sequim, working on a farm to raise funds to get back to Alaska.

Throughout the morning, Team Sea Runner flops gently over the waves in their science experiment. Rescue boats motor up, especially after Nielsen makes the decision to detour 15 or so miles around Protection Island, but he brushes off the assistance vessels with friendly banter. Then the team’s radio crackles: headquarters. “Team Sea Runner,” says a voice. “Team Sea Runner, please respond.”

Nielsen tries to reassure them, but the channel seems jammed up.

“Fuck ’em,” he says, stowing the radio. “They don’t need to know what’s going on.”

Around 1 p.m. he looks at his iPhone, tracking the other teams’ progress. Most have already made the crossing.

He says, “They’re all thinking, Those guys have tarp sails, they’ll never make it. I don’t care. They have high-tech stuff. But if it breaks, they can’t jury-rig it!”

It doesn’t take acute powers of deduction to see that Nielsen thinks he can win this thing, passing all those shining tris and cats as they beg for tows in some haggard cove. He has everything planned in granular detail, from daily calorie targets (6,000, much of it in salted olive oil) to defecation strategies (a canvas funnel). That amber Viking warrior stone? It belongs to Nielsen.

Veirs, on the other hand, isn’t feeling particularly competitive. He is more interested in exploring the coast and discussing the philosophy of Polynesian watercraft. Soon after Nielsen’s rant, Veirs offers up a contemplative discourse on orca biology.

At about 6 p.m., when they’re just a few miles from Victoria, they suddenly start moving backward—a flooding tide. The guys try to tack out to sea, but the current gets stronger. Around 7:30, they pull up to a rocky beach at the far eastern edge of Vancouver Island, just before getting flushed clear to Washington State. They are tying up to a kelp bed, preparing to spend the night, when a small yacht approaches and a white-haired man calls out: “How you doing?”

It’s Veirs’s dad, Val, who has been following them on the race tracker on the Race to Alaska’s website, along with some eight million other fans. Nielsen hisses, “They can’t help us.”

They chat briefly, then Dad motors off and Nielsen remembers something. He sailed these waters back when he was a twenty-something hotshot with the Canadian coast guard. There’s a sheltered route around the back side of a small island—he once wrecked a girlfriend’s boat there. The guys pedal into a calm channel. Eagles flap above abandoned beaches; seals play in the shallows. The falling sun seems to take Nielsen’s competitive fire with it. “Why,” he asks, “would you race through waters like these?”

George Corbett of Team SeaWolf stands shirtless on the dock in Victoria, a wild grin on his face and a cigarette in his mouth. Piles of ramen noodles lie at his feet. It’s two nights after the qualifying leg, the eve of the real race. Tomorrow he’s going to quit smoking. Tonight he’s lighting new cigarettes with the ends of old ones.

The 28 teams that survived the qualifying stage are all moored in Victoria’s well-appointed harbor, surrounded by food carts and buskers. When an onlooker approaches Corbett to ask about the boat’s foiling system, he points to McCormack, his long-haired and tattooed partner, who is messing with a tangle of rigging. “It’s like spaghetti,” Corbett says. “Stick a fork in and twirl. See what you get.”

McCormack works away silently. They have repaired the mainsail that tore on the crossing from Port Townsend, but there’s still much to be done: food to pack and rigging to fix. “Shit show,” explains Corbett succinctly. It will take well into the night. But then Corbett stomps out his cigarette and abruptly announces that he has scored a Tinder date with a cute Victoria neuroscientist. “She cuts open mouse brains and shit,” he says. “I gotta go.” He shakes his head, apologizes to McCormack, and leaves.

Nearby, Tripp Burd stands by his catamaran, looking far less confident than he did in Port Townsend. The brothers made the crossing to Victoria in just over four hours, coming in second. But last night, all qualifying racers attended a mandatory safety briefing by the Canadian coast guard’s regional search and rescue supervisor, Susan Pickrell, a no-nonsense woman who noted that there’s only one rescue chopper for the whole coast. “So if you think a helicopter is going to fly out and come pluck your ass out of the water, it’s not gonna happen,” she said. She also added that survival time without a drysuit could be up to three and a half hours, depending “on how fat you are and how much will you have to live.”

Tripp now looks like a kid deeply out of his element. He and his brother have done multi-day races before, but that was in Florida, and hotels were involved. Their initial plan for this event was to sail all day and night, but other competitors have warned them about the dangers of speeding through log-filled channels in the dark. Now they’re planning to anchor in coves at night and sleep in drysuits on their tarpaulin. Their boat has no other shelter. “I’m scared to death,” he says.

The next day, Sunday, June 7, the 68 racers gather at noon near a statue of Captain Cook—an inauspicious icon, maybe, but the only one available. It’s a LeMans start. Beattie sounds a horn, and the crews run down to their boats. Team Sea Runner is first off the dock. The real race is on.

It's always dead calm before a gale.

For the first few hours following the departure, there’s no wind and the fleet sticks together, inching north through Haro Strait to the town of Sidney, where the Gulf Islands create a maze of small channels that present the first opportunity to choose your own adventure.

Everyone has the same goal: to reach the town of Campbell River, 120 miles up the Strait of Georgia and roughly one-fifth of the way to Ketchikan, by Monday evening, the second night out of Victoria. That’s when an ebbing tide will push through Seymour Narrows, a churning ocean river that feeds into the second major test of the course, Johnstone Strait. The boats that make the Monday evening tide at Seymour Narrows should be the ones to beat, soaring west and then north into open waters while the rest wait eight hours for the tide to shift again.

How they get to the narrows, though, is a matter of choice. When the leaders of the fleet reach Sidney, in front is Team Soggy Beavers in their rowboat, followed by a scrum of boats. Then a gentle southerly picks up, allowing the bigger boats to unfurl their sails. The fleet splinters.

Team Elsie Piddock flies out in front, followed by Team FreeBurd. Hughes’s plan is to stay in the calmer waters to the west of the Gulf Islands, then duck out into the open Strait of Georgia as late as possible, since the forecast is calling for headwinds starting at midnight.

A few teams opt to head into the Strait of Georgia early, Sea Runner among them. Around 10:30 p.m. on Sunday, Veirs is at the helm, cruising along into the sunset, when he sees humpbacks feeding near Saturna Island. The biologist smiles and follows them north into the Strait of Georgia. Then the wind dies. Dead calm.

Suddenly, a fierce headwind kicks up from the north. It gets dark, clouds obscuring the moon. The waves grow to six feet. Veirs tries to pound upwind, but a gust rips off the boat’s larger tarp sail and it falls on Nielsen’s head. He springs up and stands on the bow, boat rocking in the waves. He has a plan: “Scott, I’m going to stand here while you stand on my wrists and raise the other sail!”

Veirs furls the fallen sail, grabs the smaller one, and jumps up onto his partner’s forearms. Somehow they don’t buck off the boat, and Veirs manages to rig up the sail.

About this time, Team FreeBurd is 20 miles north, charging through the strait. Their catamaran climbs up one wave and dives five feet into the trough of the next. A cylindrical shape flashes in the bioluminescence directly off the bow: a log the size of a telephone pole. The impact sounds like a gunshot. The brothers limp to a protected cove, where they discover that their hull survived. They put on a smaller reef sail and set back out. It promptly tears off twice in a row.

Team Elsie Piddock, meanwhile, cruises on. By Monday afternoon, Al Hughes and crew have reached Campbell River. They fly through Seymour Narrows on an ebbing tide, leaving the fleet in their wake. “The rich,” Hughes will explain later, invoking a sailor’s favorite cliché, “got richer.”

At the same time, the poor are getting poorer. By Monday afternoon, while Elsie Piddock shoots through Seymour Narrows, the rest of the fleet is scattered throughout the Gulf Islands, seeking shelter. FreeBurd is one of many teams repairing wind-ruined rigging in the various marinas that dot Vancouver Island’s coast. Mann, the solo South Carolinian, pilots his Hobie through the quieter inland waters, making slow, steady progress. Team SeaWolf, meanwhile, decides to gamble.

They entered the Strait of Georgia on Sunday night, within sight of three other boats. But by Monday afternoon they’re alone; the others have all reconsidered their routes or bailed from the race completely.

But the way the Squamish boys figure it, you can’t foil without wind, so they decide to stay in open water. At about 6 p.m. Monday, the 25-knot gusts lie down, and Corbett sets a northwesterly bearing.

Then the wind picks back up. Hard. By midnight it’s gusting to 30 knots from the northwest, pushing against the tide. The waves are so steep, Corbett can’t tack safely. Soon he’s heading southeast, toward the Fraser River delta, where the water gets shallow, kicking up dangerous waves.

McCormack tries flanking their bow with paddles in order to help them turn. But the foiling boat has too much sail up; attempting to reef it in these conditions, or even for the guys to switch positions on the boat, would cause them to capsize. They try to have normal conversations in order to stay calm: Do you want kids? How did it go with the mouse-dissecting neuroscientist? Then a massive wave washes over them.

When they’re about a mile offshore, Corbett says, “I think we gotta face the music.” He has been fighting in a blender for nine hours. McCormack argues briefly, but at around 3 a.m. they radio the Canadian coast guard. Soon a hovercraft crashes up through the waves and the guys scramble aboard. Their boat is later found floating hulls up somewhere near the town of Richmond, British Columbia.

“If you’re going to wreck,” George will later say, with a hint of something like pride in his voice, “you want to do it with a bit of style.”

As the winds continue to roar, Mann spends three days making slow progress through the Gulf Islands, well behind the leaders of the fleet, before poking out into the Strait of Georgia. He pulls into Campbell River on Wednesday afternoon, ties up to a pier, and walks to a McDonald’s, where he consumes four consecutive Big Macs. Then he falls asleep in a laundromat while drying his clothes. At 11 p.m., he makes the curious decision to catch the next tide through Seymour Narrows, which arrives at 1 a.m. “I’m in a race,” he will later explain. “The night doesn’t scare me so much.”

In three hours, he’s heading into a 20-knot northerly under a full moon. The tide is at his back; the waves are steep, eight feet high and three seconds apart. Whirlpools swirl. He dives into a trough, and before he can look up a wall of ocean falls on his head, driving him off his boat into the dark, frigid water. He’s tethered to his cockpit with a surfboard-style leash, and he pulls himself back in. High basalt walls loom on either side of the narrows, offering no place to land. He eventually emerges at a little bay, drops anchor, and sleeps for six hours.

Early the next morning, he heads into a thrashing Johnstone Strait. The water fills his boat, drowning his electronic chart plotter and his GPS device and forcing him to resort to paper charts. He begins to shiver almost constantly. He camps on a beach but misjudges the tide and wakes up when a wave washes him off the logs he’s sleeping on. He starts to feel the cold in his eyeballs.

Over the next week, Mann loses track of the days. Hallucinations set in—trees, mostly, but also a barrel of laughing monkeys and a supermarket full of Mountain Dew. He ties up to a kelp bed, gets lost in the fog.

On the water again, he’s spotted by Team UnCruise, an Alaskan sailor competing, along with his daughter and her boyfriend, on a trimaran. They give him a hot meal. Mann emerges into Queen Charlotte Sound invigorated. “I came out with a whole new perspective after five days straight of kicks in the head,” he says later. “I thought, It’s all got to get better, because it’s not going to get any worse.”

The next evening, Mann spies a beautiful beach near Cape Caution and makes for it, envisioning a campfire. But the waves pitchpole him stern over bow into the surf. His mast hits the shallow seafloor, and another wave buries him. His drysuit is open at the zipper—a grave error committed in the name of convenience—and seawater encases his legs like icy concrete. He drags his boat onto shore by his arms, reaches into his life vest, grabs a knife, and slices open his drysuit. Eighty pounds of Pacific Ocean pour out. He strips down and starts a fire.

Mann spends the night retrieving what he can from the beach. A few essential items don’t wash up, including his anchor and his desalinator. The next morning, he shoves off again in his spare drysuit and runs into Team Blackfish, a three-man crew on a sleek catamaran whose captain forces Roger to spend the day on board drinking tea.

Over the next week, Mann loses track of the days. Hallucinations set in—trees, mostly, but also a barrel of laughing monkeys and a supermarket full of Mountain Dew. He ties up to a kelp bed, gets lost in the fog. He gets washed off logs again while sleeping. Mosquitoes swarm him. Dahl porpoises circle his boat. He figures he loses 20 pounds. It is an awful, beautiful experience.

On Saturday, June 20, two weeks after leaving Victoria, he pulls around the bow of an immense Disney cruise ship in Ketchikan. He spots a small dock with about 15 people on it. One of them is a customs official, waiting to find out if he’s bringing any dairy products into the United States. Another is a race fan in a kilt who says that the Iditarod has nothing on this and offers Mann fish and chips. He devours the food with difficulty, since his fingers are the size of sausages. In a flat voice he says, “I came through a lot of stuff. Everything hurts but your heart and your soul. It’s good to go. It’s intact. You’re like, OK. I got this.” He pauses. “And then you get kicked in the head again.”

He flies home the next day and leaves his boat at the dock. He says it’s a gift for Jake Beattie.

Team Elsie Piddock wins the Race to Alaska in just five days, at one point flying 120 miles in a single tack. When they reach the pier in Ketchikan, on Friday, June 12, about 40 fans and a handful of local reporters are waiting. So is Beattie, with the cash nailed to a piece of wood.

Another sleek trimaran crewed by Team MOB (Mail Order Bride) Mentality comes in second on Monday, June 15. Team Por Favor, in a 33-foot sloop monohull, is so close behind that MOB Mentality splits the steak knives with them. The Burd brothers take fourth place.

Fifteen teams finish the race. Legends begin to circulate among boat enthusiasts. The Elsie Piddock cost a million dollars (false). A freighter smashed a vessel on the opening crossing (also false). Multiple teams took extended pauses before reentering U.S. waters to polish off their marijuana stores (unverifiable).

The teams trickle into Ketchikan throughout June. One young man in a classic monohull pulls up to the dock in the early-morning hours of June 20, sees a few cameras, and declares he is on the verge of a nervous breakdown. On June 26, a 71-year-old arrives with his 26-year-old first mate, having spent the morning jury-rigging their broken rudder. He steps ashore and says simply, “I do this stuff.”

Team Sea Runner bows out north of Johnstone Strait after two weeks, one dismasting, and more than one verbal sparring match. They come back a few weeks later to retrieve their humbled craft and tow it to Veirs’s Seattle garage.

On June 29, Beattie sits in a café in Ketchikan, eating scallops and thinking about the future. Nearly nine million people have visited the race tracker. Some were inspired to chase down their favorite teams along the way to offer up high-calorie gifts: canned venison, beer, a tub of ice cream for Roger Mann. Beattie has fielded calls from reality-TV producers and potential big-dollar sponsors. That might be a good thing. It might not.

Now, though, only three vessels are still out there. Beattie checks the race tracker on his iPhone and gets up suddenly. One of the boats is coming in. He runs over a bridge and across a parking lot, making for the pier. Slowly at first, then faster, trying to reach the dock before the racers arrive. They’re rowing a beautiful little monohull that they salvaged out of a blackberry bush. It’s the kind of boat this race was made for. Beattie tears down the streets in a dead sprint. He arrives just in time to see a haggard man hop out of the craft and scream, “I truly think everyone should do this!”

Contributing editor Abe Streep () wrote about Greenpeace international director Kumi Naidoo in April.