As I walk into the Timorese surf, Wayne Lovell checks my scuba gear one last time before we drop down to the coral reefs 40 feet below. If any sharks are around, I’ll follow his lead. Lovell, a former war-zone television cameraman for Reuters, has been to hellholes like Bosnia, Somalia, and Zaire. No mere shark is likely to rattle this rough-cut Brit. And if sharks underwater don’t scare him, neither do conditions elsewhere in East Timor. Lovell runs a dive shop in the capital, Dili, population 50,000. He thinks East Timor is paradise found. For the rest of us, it’s more like paradise with an asterisk.

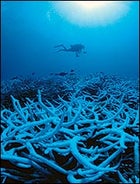

Spoils of Détente: diving among staghorn coral

Spoils of Détente: diving among staghorn coral After 400 years of Portuguese rule, 24 years of Indonesian military occupation, and two and a half years of bumbling United Nations administration, East Timor finally emerged as the world’s newest country on May 20, 2002. Ten degrees south of the equator, in the Lesser Sunda island chain between Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea, the mountainous, reef-fringed nation (population 800,000) occupies the eastern half of the 13,094-square-mile island of Timor, the western half of which is Indonesia. With an economy based on subsistence fishing and agriculture—supplemented by a good deal of international aid—nearly half the country’s residents live on less than 55 cents a day, ranking them among the world’s poorest. Tourism was stifled between 1975 and 1999, when Indonesia largely banned foreigners in order to have a freer hand to fight independence guerrillas. Today, those former guerrillas run the show, and they’re eager to make up for lost time, hoping that peace will lure travelers to this place Lovell calls home.

But even to rough-and-ready tourists like me, the country’s war wounds are evident. Many of East Timor’s buildings are gutted and roofless. Electricity is sporadic, and the tap water undrinkable. The only real hotels are in Dili, and they range from converted shipping containers to old hotel properties being refurbished by Portuguese investors. ���ϳԹ��� Dili, the few existing guest houses generally offer plywood beds with a little padding and a mosquito net. There’s always camping, but it’s necessary to negotiate with a village leader before your tent is staked, since intricate local property rights vary.

If you can handle these less-than-four-star accommodations, East Timor is rich with arms-free, all-natural adventure. Eighty miles southeast of Dili is the 225-square-mile Lore Reserve rainforest. It is dominated by a 3,000-foot peak known in the local language, Tetun, as Foho Lalehan (“Sky Mountain”). For years, East Timorese national hero Xanana Gusmao’s forces harassed Indonesia’s military from camps within the dense forest. Now Gusmao is East Timor’s first elected president, and he’s encouraging his former troops to go into business guiding eco-treks up the peak.

Offshore, East Timor is even more interesting: In surfing circles, rumors circulate of beautiful breaks near the south-coast town of Viqueque. And of the several hundred miles of reefs, only a few miles have been dived. Years of low-level fishing, an absence of industrial pollution, and a steady flow of cool, nutrient-filled waters from offshore trenches have kept the coral in excellent health.

I decide to take a look for myself, so Lovell and I swim 60 feet off K41 beach, 25 miles east of Dili, and dive 40 feet down to the sandy bottom to explore three-story coral walls where mobile-phone-sized lionfish splay poisonous fins in gestures of defiance, and clown fish dart about with dizzying speed. Looming barrel sponges appear large enough to swallow me whole. After 50 minutes, I’ve sucked my tank dry. As we surface and swim to shore, I feel a rumble. It’s not sharks, though. It’s peacekeepers rattling by in a heavy Humvee on the coastal road to Dili.

Back on the beach, Lovell slips out of his gear, tosses a few pieces of steak onto a barbecue, and joins in a round of volleyball with his Timorese friends. After quitting his cameraman job, Lovell traveled the world for almost a year, looking for the perfect place to open his scuba-dive shop. He visited Dili in December 2000 and returned a month later to settle. Is he nuts? Time will tell.

“East Timor’s a bit like the Old West, filled with mercenaries, misfits, and missionaries,” he says with a smile. “This place is right up my alley.”

»���ұ�ճ�

Australia’s Air North (011-61-8-8945-2999, ) flies to Dili from Darwin, Australia, for $203 one-way.

»CAR RENTAL

Rental agencies including Aust-Asia Car Rental (011-61-408-836-629, ) line the roadway between Comoro Airport and Dili. Sedans rent for about $44 per day; four-wheel-drive vehicles cost about $66 per day.

»�᰿�շ�����

You’ll find a reasonably up-to-date list at. Try the Timor Lodge Hotel, just outside the airport and about three miles from downtown (doubles, $55; 011-61-408-836-629, ).

»WHEN TO GO

The dry season is late April to October. From November through mid-April, rains wash out the more poorly maintained roads.

»�ٱ��ձ�����

Lovell’s shop, The FreeFlow (PADI), in Dili, offers two-tank dives for about $100, including transportation and food (011-61-419-817-826, ). Dili Dive (NAUI), also in town, charges $35 for a two-tank dive, including transportation (011-61-409-276-850, or e-mail the shop’s Australian affiliate at coraldivers@bigpond.com ).

»GENERAL INFORMATION

Call the former East Timor tourism minister, Vincente Ximenes (011-61-407-971-123). He and his four-member staff will make arrangements for visitors.