NIGHTTIME COMES IN THE FORM OF LIGHT rather than darkness when you’re hanging around the waterfront in Seattle. Airplanes crisscrossing overhead turn into flashing pinpricks of green and red, and the Space Needle, at the foot of Queen Anne Hill, blazes alive like a desert casino. Soon the lights from ferry terminals, souvenir shops, and clam chowder joints glitter across the surface of Puget Sound, and the waterfront’s numbered network of piers becomes a meeting ground for skate punks, panhandlers, yuppies, cops, drunk students, random passersby, and tired tourists dragging their crabby kids.

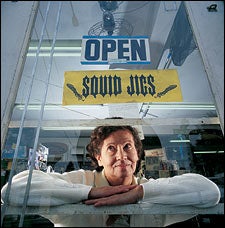

Maria Beppu, co-proprietor of Linc’s Tackle in Seattle

Maria Beppu, co-proprietor of Linc’s Tackle in Seattle

Sometimes, though, around December, when the solar calendar and the lunar phase align with the earth’s rotation just so, an entirely different kind of nighttime meeting occurs here, and all hell breaks loose. Millions of creatures rise out of Puget Sound’s depths and look to the emerging lights of Seattle with hungry eyes. Each slimy and voracious predator is armed with ten sucker-bearing appendages, a jet that shoots an inky substance to confuse its enemies, a sharp, pointy beak used to gouge hunks of flesh from prey, and the ability to dodge forward, backward, sideways, or in a 360-degree turn with lightning speed. No anchovy or crustacean is safe from Loligo opalescens, otherwise known as the Pacific, or market, squid. And no squid is safe from the Seattle squid jiggers who flock to the docks at dusk and stay into the wee hours of the night, hoping to catch a few.

I first heard about squid jigging from my longtime buddy Matt Drost, a 30-year-old graduate student and bluegill-fishing Midwesterner who’s lived in Seattle for five years. His message on my machine—”We’re seriously missing out, man; we should be squid jigging”—had the urgency of someone recently hooked into a pyramid scheme. I live in Montana, where fishing becomes nauseating in its predictability: white people in brown fishing vests, all catching trout. The opportunity to outwit a close cousin of the notoriously crafty octopus and the vicious giant squid was very tempting. Plus, killing a squid and eating it isn’t looked down on like whacking a trout is, probably because trout seem serene and gentle, whereas a squid looks like it would kill you if it had the chance.

When Matt, who by now had gotten a taste of jigging himself, phoned again to announce that the peak of squid season would coincide with his winter break, I bought myself an insulated one-piece mechanic’s suit for 20 bucks at a pawn shop, figuring I’d wear it over my styling duds to keep them free of squid ink. I threw it into the trunk of my gray ’87 Subaru and took off.

A BASIC JIGGING SETUP involves a standard light rod and reel, a portable floodlight, and a handful of lures known as squid jigs.

Squid-jigging success rests on the jig itself, a five- or six-dollar contraption engineered for cold-blooded simplicity. If you’ve ever watched a jig bob up and down in the water, you know why its name was derived from the word for a lively dance. The top end of a jig is shaped like a pinkie finger and decorated like a small, flashy fish. The bottom end of a jig sports a profusion of J-shaped needles. A squid doesn’t bite the jig and get lip-hooked in the conventional way that fish do. Instead, a squid seizes the jig with its tentacles. The jigger must detect the squid’s presence through the rod, then yank on the line to impale the squid on the needles. In winter, when large numbers of squid congregate to spawn, they feed voraciously in the shallow waters at night, gobbling up anything that’s smaller than they are. The jig simply has to look alive.

If you ask around on the docks about where to buy a jig, you will wind up with directions to Linc’s Tackle. This dusty but well-organized fishing shop lies east of the waterfront, in the International District. The shop’s founder, Lincoln Beppu, was born in the United States to Japanese parents in 1912 and died in 1992. He opened the corner-store business on Rainier Avenue South and King Street in 1950, about five years after he and his brothers, Monroe, Taft, and Grant, were released from a World War II internment camp for Japanese-Americans.

Lincoln Beppu recognized that his neighborhood clientele of Asian immigrants did not have much in the way of disposable income, so he encouraged squid jigging on the grounds that it was cheap and close by, and that you could get a good meal out of it. Lincoln imported many of his jigs from Japan. People have been catching squid in Asia and the Mediterranean for thousands of years, and many centuries ago the Japanese began whittling, from deer antlers, intricate and decorative jigs that look almost exactly like the ones used today. These ancient jiggers lured their quarry with torches instead of halogen lights.

Linc’s Tackle is now owned by Lincoln’s son, Jerry Beppu, a 57-year-old man who wears his graying hair slicked back in a way that accidentally appears hip. Jerry’s wife, Maria, the daughter of a French-Canadian mother and a Filipino father, helps run the shop. In the window of Linc’s Tackle is an old, yellowing sign that says LET’S GO SQUID JIGGING: COME IN FOR ADVICE AND TACKLE.

Matt and I caught Jerry and Maria during their evening rush, which coincides with the setting of the sun. Jerry was peeling a tangerine and Maria was pantomiming back and forth with a man who spoke neither English nor Japanese. She pointed to each available size of jig, which vary in length from a ballpoint pen to a pen’s cap, and waited for the customer to nod yes or no. He picked his size. Then she went through the colors, which range widely. Some are plain neon yellow and others are obviously inspired by an appreciation for the psychedelic.

I gazed over the man’s shoulder and spotted the squid jig of all squid jigs. It was a beauty: a glow-in-the-dark jobby with a translucent top revealing an internal swirled cat’s-eye design. Based on zero experience, I knew this jig would work. It cost me $3.25. I also forked over $23.90 for a one-year out-of-state shellfish license ($8.67 for Washington residents). Matt picked out a handful of trusted jig designs, and we headed for the door. As we stepped outside, Jerry Beppu yelled, “Patience and luck!”

RIGHT ABOUT DUSK we drove under the Alaska Way Viaduct, near Pioneer Square, a historic district of restaurants and trendy shops a block off the waterfront. We parked between an idling limousine and a man sleeping beneath a blue plastic tarp, walked across Alaska Way, and headed north, “up the Sound,” keeping an eye out for anybody who looked like he might be getting ready to jig some squid. It was still a little early and no jiggers were at Pier 63, the most popular gathering spot for jigging, so we decided to try a rogue move and jig Pier 57, a few blocks south behind Fisherman’s Restaurant and Bar and a kitschy art gallery called Pirate’s Plunder.

I’d pulled the battery out of my Subaru and lugged it along with us. We took two pieces of copper wire with roach clips, ran them from the battery to an AC/DC inverter, and plugged in a big-ass, 2,070-lumen floodlight. When I shone the light on the water, I swore it would parboil any squid that happened along. As we were messing with this outfit, a professional-looking man in his early fifties wearing dress slacks and a trench coat came out of the art gallery.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

I figured he was there to kick us off the pier, but we didn’t bother lying. “We were thinking we might try to catch some squid,” Matt said.

“You got a light, huh?”

“Hell, yeah,” I answered. He went back inside. In a moment he returned with a fishing rod.

It got so windy that I wrapped a bungee cord around my head to hold my hood in place. We drew quite a crowd as it got dark. The art gallery guy’s daughter showed up with a fishing pole and her boyfriend. Another guy and girl of about college-freshman age walked up to ask what we were doing. I told them, and they got comfortable leaning against a rail, like they were going to stay until it happened. A man in a red leather jacket walked up. “What you catch?” he asked. He spoke with an Italian accent.

“Squid. You like squid?”

“Yes, I cook many ways,” he said. Several other people crowded in close to the light, putting rods together.

I’d never caught a squid, so I wasn’t sure what to expect. Puget Sound is also home to the mysterious giant squid, so it was with some trepidation that I lowered my psychedelic jig into the water.

I looked over at Matt. He had his jig in the water about halfway to the bottom, which he said was 20 feet down.

“You want to move the rod up and down,” Matt suggested. “Real lightly.” Within seconds I became aware that a squid was groping my jig.

I cranked on the reel, and a squid emerged in a fury of squirting ink and grappling tentacles. Even though it was only about eight inches long, an average size, I was struck by the memory of those sea monsters that destroy Tokyo in old Japanese movies. A sea-monster scream seemed so apropos to the squid’s emergence that Matt provided one, a habit of his that I adopted as my own. It was a shrill screech, sort of a gusheegushowee. As I jacked the squid over the rail, it landed a shot of black ink right on the chest of my coveralls, forming a kick-ass badge. I announced that from now on, I would answer only to Sheriff Squid.

The squid gurgled and changed colors from white to red to brown, like a chameleon wired on speed. At the top of its body a round head with two large eyes formed the base for eight arms and two spindly tentacles. The body, a fleshy cylinder called the mantle, resembled an occupied condom. A thin, cellophane-like shell gave the mantle a slight rigidity. Looking at a squid, you’ve got to hand it to whoever started eating them. What an open-minded individual! I dropped the squid into my bucket and tried to visualize the legal daily limit of ten pounds.

AN AGGRAVATING TING about squid is that they’ll clear out at any moment, without warning. That’s what happened at Pier 57: Just when I was getting my groove and had enough squid to cover the bottom of a five-gallon bucket, we had a squid shutdown. All the folks sharing our light packed up and headed a ten-minute walk north to Pier 63 without so much as a good-bye.

Matt and I followed. Pier 63 was now a big party. A generator powered a large bank of floodlights, and a crowd of 50 people or so was lined up in the glow. People were dropping jigs down into what looked like a docking slip for a large ship.

The generator’s owner, a frail old Korean man, was warming his hands in the buzzing machine’s exhaust. “I don’t jig much myself,” he told me. “I just use my lights so my friends and neighbors here can have a good time.” I asked him his name, but he wouldn’t say, because you’re not supposed to use gasoline-powered equipment on public piers. Now and then some pain-in-the-ass type will file a complaint and the cops will be forced to shut him down. “When they do, I cool it for a week and then come back out like nothing happened,” he said.

Matt and I thanked him and squeezed into the line. I was standing next to a 52-year-old Cambodian man named Savuth Thach, who was dressed from head to toe in the plastic bags that car dealers send your old tires home in when you buy new ones. He gave us some dried squid. While I chewed, he told me that he’d fled Cambodia in 1975 when the Khmer Rouge took power. He caught squid back in Cambodia by dragging a white rag through the water to lure them up to the surface, where he could net them. “A squid thinks the jig is another squid and wants to mate it, not eat it,” Savuth told me. I wasn’t going to challenge this theory; Savuth had way more squid in his bucket than I did.

“So do you, like, work the jig in a sexually provocative way?” I asked.

“No, just jiggle and feel,” he said, yanking in another squid. “Just jiggle and feel.”

Farther along, I met a 30-year-old Filipino named Rudy, who makes his own jigs out of lead, straight pins, and glow-in-the-dark tape. He used to catch squid in the Philippines by throwing dynamite into the water. The explosion would stun the schools of squid, making them easy to net. These days he gives some squid to friends and uses the rest to make a traditional Philippine dish called adobo, with squid marinated in vinegar, garlic, soy sauce, bay leaves, and crushed peppercorns, then cooked and served with rice. I asked Rudy if he thinks a squid wants to mate with the jig.

“The squid wants to fight the jig,” he said, “or maybe mate it.”

The mood on the pier suddenly turned serious. Some good schools of squid had moved in, and everyone was concentrating. Matt and I crowded into a gap amid a group of Japanese-American college students. They were fixing to make some ika sansai, a cooked-squid salad. So many squid were getting cranked up over the rail that the pier’s surface was slimy with ink. No sooner would you drop your jig down than you were pulling up a squid. Matt and I had been providing sea-monster screams for everybody in our area, but the responsibility had grown too demanding. From then on we screamed only for our own squid.

At one point Matt took a shot of squid ink right in the eye and had to retreat momentarily. The ink is harmless, but it stings a little. As he recoiled, his place was seized by a little old Thai lady in a plastic bonnet who’d been weaving through the crowds searching for primo spots. The woman wanted squid, and she didn’t want to stay up all night getting them. She set a small stool down, climbed up so she could reach over the rail, and set into a punishing bout of squid jigging. She’d lower a jig down and stare out over the harbor for a moment. Then, as though she’d been struck by a brilliant idea, she would crank up the lure with a squid attached, give the creature a second to expel its ink away from her clothes, and flick it into her bucket. Several times she pulled up her jig with two squid attached. I couldn’t help but let out a double monster scream, which failed to amuse her. She’d jiggle her bucket a bit after every catch, as if assessing the needs of several recipes. After she had a couple pounds, she gathered her things into a basket and left.

The squid kept coming. The fishing motif of “first, biggest, and most” was totally absent. There wasn’t a trace of that usual pier-fishing possessiveness about who’s standing in what spot. The collective goal was for everyone to get something. Rudy was lending out his homemade jigs left and right. One guy with a hot spot next to a pylon kept waving everyone over. When a woman’s jig got caught on the pylon, all activity in her area stopped until it was freed.

THE EVENING’S RUN of squid lasted until about midnight. It was one of those all-consuming, action-packed stretches of time when you can’t even think about the things you’re supposed to be doing with your life. The catch tapered off until you had to look around for a few minutes to see somebody pull one up. At about 1 a.m. the gang trickled away. If someone’s bucket was low on squid, the folks with good catches poured in a few. And then everyone headed up the hill, back to the lights of the city.

Matt and I caught about ten pounds of squid that night, and it took days to cook them all up. You can eat everything on a squid but the beak, shell, and eyes. We cut the bodies into strips and covered them with pasta sauce. We stuffed them with cheese and mushrooms. We blanched, broiled, and boiled them. But my favorite recipe was the simplest: Squeeze the ink into a pan, add butter, then cook the squid for a minute or two. Squirt with lemon and eat. Then, before the pan cools, suck back the ink. Swish it until your teeth are coated good and black. Then smile at your friends—or, if you’re alone, at the mirror. Big smile. You’re an American squid jigger.