“Summer means many different , in his home.

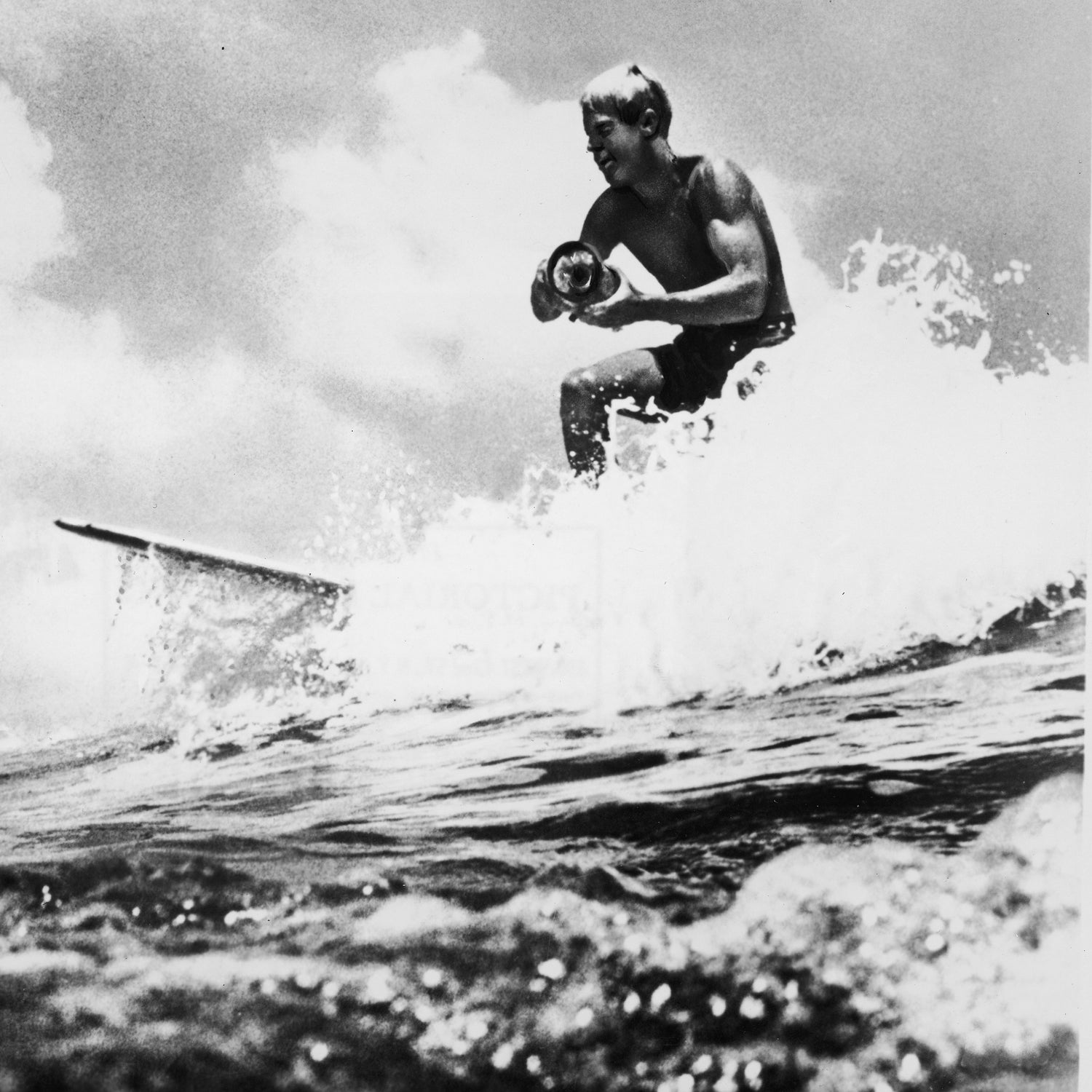

Ostensibly a tale of two surfers chasing perfect waves,��The Endless Summer is better understood as the original outdoor-sports lifestyle fantasy, the Dead Sea scrolls upon which our entire climbing/surfing/skiing road-trip religion was founded. With Brown narrating in a sun-saturated and cracker-jack American patter, the film opens with a montage/primer on the sport of surfing, just to let viewers know how much fun those crazy kids are having on the coast. Then it follows clean-cut longboarders Mike Hynson and Robert August around the world to Senegal, Ghana, South Africa, Australia, Tahiti, New Zealand, and Hawaii.

Brown was a fledgling surf filmmaker when he made The Endless Summer for $50,000. He initially screened the film, in 1964, the same way everybody screened surf films in those days, driving up and down the west coast booking auditoriums and church halls, selling tickets, playing records, and narrating live. All by himself. After two years of that, Brown was so convinced The Endless Summer could sell to a broader audience—and so frustrated with movie distributors telling him it couldn’t play inland—that he rented the Sunset Theater in Wichita, Kansas, for two weeks. The place sold out, so Brown pulled the same trick at a theater in New York City and landed himself a theatrical distribution deal.��Newsweek soon called The Endless Summer one of the ten best films of 1966,���վ����� magazine called Brown the “Bergman of the boards,” and the film grossed $30 million worldwide.��

As Matt Warshaw writes in ,��the actual wave-riding in The Endless Summer was badly outdated almost as soon as middle-American audiences saw it. Surfboards had gotten much shorter in the intervening three years, and surfers were already making the switch from old-school longboard technique to modern slashing-and-carving. Same for the personal style of the surfers themselves, whose buzzed hair and propensity to wear suits and ties on airplanes looked downright square as early as 1967. So it’s a testament to the power of Brown’s vision that The Endless Summer still became a one-film culture industry, a touchstone for every outdoor-sports travel documentary from the legendary 1968 Mountain of Storms,��in which North-Face founder Doug Tompkins and Patagonia-founder Yvon Chouinard drove a VW bus to South America surfing and skiing and climbing along the way, to the spellbinding new ,��about Aamion and Daize Goodwin’s global surf travels with their beautiful kids.��

Bruce Brown was born on December 1, 1937, in San Francisco. He lived in Oakland until age nine, then moved with his family to Long Beach. He started surfing at eleven and saw early surf movies at the local Elk’s Club. He joined the Navy out of high school, served on a submarine, and shot his first hobby film with an 8mm camera while stationed in Honolulu in 1955. After he was discharged, Brown came back to California and went to Long Beach City College, but dropped out to work as a lifeguard.

The first big surfing boom, touched off by the bestselling book and Hollywood movie Gidget, was just getting rolling when Brown landed a job at Dale Velzy’s surf shop in Manhattan Beach, California. Velzy saw Brown’s home surf movies and started screening them for paying customers, charging 25 cents admission. Soon, they’d negotiated a deal for Velzy to bankroll Brown on a trip back to Hawaii, with funding for a proper movie camera, 50 rolls of film, six plane tickets, and Brown’s living expenses. The result was Brown’s first feature-length documentary,��Slippery When Wet.��Four more followed, at a pace of one per year: Surf Crazy (1959),��Barefoot ���ϳԹ��� (1960),��Surfing Hollow Days (1961), and �²��ٱ�����Dz��������(1962).��

“When Bruce made The Endless Summer,��in 1963,” says Warshaw, “it looked like some obscure guy stepped up to the plate and hit a homer, but the truth is he’d been doing rough drafts for years. In all those earlier movies, you can see him working out camera angles and that patter and voice.”

After the runaway success of The Endless Summer, Brown partnered with Steve McQueen to make a documentary about his other big love, off-road motorcycle-racing. The resulting documentary,�� (1971), was nominated for a 1972 Academy Award. Brown spent most of the next two decades riding motorcycles, fishing commercially with his own swordfish boat, surfing, and racing rally cars with his wife, Pat. In 1994, Brown came out of semi-retirement to make The Endless Summer 2 with his son, Dana, whose Step Into Liquid (2003) was the fifth-highest grossing sports documentary ever.��The Endless Summer 2 never matched the culture-changing power of the original but it was an awfully good time—both to watch and to film. Robert “Wingnut” Weaver, one of the surfer stars of that film, recalls painful days and creative arguments between Brown and his director of photography. “But every morning,” says Weaver, “there was a smile and a cigarette and a cup of coffee and off we went.”

Brown was also loyal to those he cared about. Weaver, who lives in Santa Cruz, California, saw him a dozen times a year in the last decade of Brown’s life. “He’s halfway between my house and where my mom lives in Newport, so we had a standing deal where I’d stop in and make dinner on the way south, and sleep over, and he’d make dinner on the way north,” says Weaver. Brown lived in a canyon off the Coast Highway near Santa Barbara. Weaver recalls the phone ringing one evening, and Brown looking out the window at a car stopped in the middle of the highway with lights blinking. It was a friend, dropping a bag of live lobsters for Brown on the median strip; Weaver had to dash through traffic to collect.

Near the end of Brown’s life, in a joint interview with Dana, Brown talked about his surfing buddies from the 1950s, how John Severson launched Surfer magazine, Hobie Alter made surfboards and boogie boards, and Brown himself took to making movies. “We just tried to figure out something to do to stay at the beach,” said Brown.��

By that measure—and almost every other measure imaginable—Brown’s life was a soaring success. Not only did he live near the water, he kept surfing well into his early 70s. “Bruce liked going with me,” says Weaver, “because after every wave he rode, I’d catch a wave myself and paddle over and find him and let him grab my ankle leash. Then I’d tow him back out for another. Bruce really lived his life in the best possible fantasy world he could’ve had. I don’t think he would’ve changed a thing.”