Until I went to the Philippines, I had been living with the delusional belief that whitewater rafting was a simple process that involved taking an inflatable boat down a river with an irregular streambed profile. Well, after a few days on Luzon, the largest of the nation’s 7,100-odd islands, I was beginning to realize that rafting in that country has as much to do with navigating Class V roads as it does with running rivers. We began in the capital, Manila, where the traffic is as crowded and tight as a raging dance party moving between the book stacks in a library. As we traveled north, the roads were still clogged—with aggressive street vendors, military checkpoints, washed-out switchbacks, and mudslides.

At play in the spray: Greg Findley at the helm on the Chico River.

At play in the spray: Greg Findley at the helm on the Chico River. Kalinga kids at the Tinglayan put-in.

Kalinga kids at the Tinglayan put-in.

Jeepney ride near Tinglayan.

Jeepney ride near Tinglayan. A quiet moment on the lower Cagayan River.

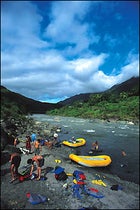

A quiet moment on the lower Cagayan River. Prepping at the Tinglayan put in.

Prepping at the Tinglayan put in. Ben, Benny, and Oliver (left to right) ready to roll.

Ben, Benny, and Oliver (left to right) ready to roll. Bridget Findley in vigilant mode.

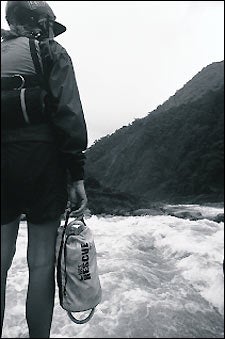

Bridget Findley in vigilant mode.

Then, as we finally closed in on the upper reaches of the Chico River, about 390 road miles north of Manila, a new roadway nemesis took the form of chickens and pigs crisscrossing in front of our vehicle, a truck/bus hybrid called a jeepney. These were no ordinary fowl and swine, either. Should a driver hit one of these chickens, he’d not only pay for that bird, but also the next three generations of lost chicken offspring. The animals were owned by the Kalinga, a highland tribe of former headhunters who have cultivated over the last several hundred years a general impression amongst neighboring tribes that it’s a bad idea to travel along the Chico. The week before we passed through, a driver hit and injured a child. I heard the settlement process broke down when the child’s father hacked the driver to death in the street with a machete.

The person in charge of seeing us through this drive and all other logistical obstacles was Anton Carag, a tall, laid-back Filipino from nearby Tuguegarao, a town along the lower Cagayan River. A politician’s son and former rancher, Anton became a whitewater enthusiast in a nation that did not have a preformed kayaking clique. But with the Philippine economy in shambles and extractive industries and damming on the rise, Anton felt that the best way to create viable jobs and promote conservation in the region was to establish an environmentally friendly adventure-travel company. So he and some partners from Manila founded ���ϳԹ���s and Expeditions Philippines. Via mutual acquaintances, they hooked up with Mukuni, a wilderness-whitewater company based in the States and owned by Greg and Bridget Findley, from Bozeman, Montana, who wanted to come over with a few clients to check out the potential rafting scene and train local guides.

The initial Mukuni plan was to do an exploratory trip on the Class IV upper Cagayan, the Philippines’ longest river, which drains the Sierra Madre in north Luzon. But then, as our group of five American clients and several Filipino guides-in-training assembled in Manila, word came that Marxist guerrillas had raided a police station for weapons. They were holed up in Nueva Ecija, along the only road leading to the river’s upper stretches. A plan that had brewed in the minds of Anton and the Findleys for two years was gone in seconds.

“There’s been a slight change of plans,” announced Greg. Anton, totally familiar with this kind of thing, just smiled and shook his head. Then he and Greg quickly began deciding what exactly the new plan would be. Fortunately, Luzon is full of wild, raging rivers barely touched by travelers. After a couple of days of logistical shuffling they had it pegged. We would travel to the jungled Cordillera Central and then raft the upper Chico River, including Dead Carabao, a Class V rapid named after a bloated water buffalo some American kayakers had found spinning in a back eddy a few weeks earlier. But before we could deal with Dead Carabao we had to get through the live hogs on the road.

With no livestock casualties to speak of, we closed in on the village of Tinglayan, which sits in the mountains on the west side of the Chico where a steep canyon wall tapers off at the narrow floodplain. Here and there, centuries-old rice terraces cantilevered out of the surrounding hillsides in descending steps. Thick stands of coconut palms and banana plants on both sides of the river jutted far above the impenetrable jungle of tangled vines. Below us, the river flowed and frothed. Roughly a hundred miles to the north, after merging into the lower Cagayan, it dumped into the Babuyan Channel between the South China and Philippine Seas.

Our jeepney, decorated with a Las Vegas slot machine/Virgin Mary motif, clashed sharply with the village dwellings, which were equal parts wood, concrete, and corrugated metal. In keeping with Philippine tradition, Anton had to find the mayor and inform him of our plans to raft the river. While he was attending to that, I checked out the arms on the older men who had gathered around the jeepney. Detailed forearm tattoos denoted “outstanding bravery,” i.e. successful headhunting forays, but over the last 40 years an elaborate series of peace treaties among the area villages has all but stopped the practice. The last real headhunting heyday was in the decade following World War II, when U.S. forces had scattered the defeated Japanese occupiers into the mountains, where many resistors fell prey to this Kalinga form of tough justice.

The mayor gave us his blessing to proceed, but he sent two guys in their late teens, Ben and Oliver, to escort us. They had no idea we were coming, but they were ready to depart in approximately ten seconds. Their gear was a pair of cutoff shorts each, and their teeth were stained crimson from chewing betel nut, a stimulant taken with quicklime and rolled into the leaves of a vine. The juice they spit trailed out behind them on the rocks and mud like blood from an elk that’s been hit with an arrow. Anton agreed to pay them $20 each for three days, a whopping salary by Philippine standards, and it seemed to be a healthy and productive transition toward procuring money instead of body parts. Still, I hoped to use Anton as a translator to ply them for a few of Grandpa’s stories about the good old days of headhunting.

It took a couple of hours to rig the two rafts. Seven little kids showed up, stripped off their clothes, and used the rafts as water slides, fearlessly slipping under the fast current and emerging downstream. The two Kalinga guides watched us loading the rafts with some interest, and then slapped the boats approvingly and put their helmets on. Ready to go. When we floated away from the shore everything turned calm and quiet—like when you leave a concert, with the rushing water providing the post-amplifier ear buzz.

Instantly, a great managerial power shift had occurred. Instead of being at the mercy of the Philippines’ unpredictability, we were now relying on the constancy of gravity. Greg Findley captained the oar raft, with a great load mounded in the back and tied down with a cobweb of blue straps. I coveted this mound dearly, figuring it to be a crow’s nest of sorts. Cindy Hanson, an amiable purple-haired graphic artist from Wisconsin, took the shotgun position in front.

The other raft was stripped bare and full of paddlers, with Greg’s wife, Bridget—a diver’s knife strapped to her jacket—yelling out commands like a guard on a slave-powered Viking ship. Her crew was an eclectic bunch. There was Dave Forsyth, an American soap-opera actor and former combat medic; Greg Von Doersten, a photographer; Anton and two of his Filipino employees, Jasper Inventor and Benny Tasi from Luzon, who were trying to bone up on rafting know-how; Shona Campbell, a camcorder-wielding American graduate student earning a film degree from the University of Montana; plus the Kalinga guides.

Water was everywhere; it rose on the rapids, it came from the sky in showers, it dripped from the overhanging cliffs, and it gushed from the hills in arcing waterfalls. Peaks on the ridgelines above rose up 4,000 feet from the river’s floor, and clouds hung from them like bits of passing thunderheads that had ripped free. Some of the ridges were topped with pine, others were rolled over with a coat of vegetation so green and thick it looked like you could pitch a tent on them. Between squalls of rain a visible haze lifted off the jungle.

In the canyon bottom, though, it was no meandering sightseeing trip. The minute we pulled into the river we were hit by near-constant whitewater. Some of the rapids ended in sharp curves that threw the boats elbow-scrapingly close to rock walls. The rest of the rapids ended with more rapids.

Late in the evening, with rain still pouring down, we pulled into camp on a small rise between the river and a stream-fed pond. A few grazing carabao kept it mowed like a lawn, and little spurts of pungent vegetation grew out of the manure piles. Anton and Jasper fried up some dried and salted squid in bacon grease and prepared tapa, a traditional Philippine dish with carabao meat (not from those carabao) marinated in garlic and vinegar and served on rice. Over dinner we cracked jokes and had a long, convoluted conversation that began and ended with whether we’d have to portage the Dead Carabao rapids.

When I got out of my tent the next morning the Kalinga guys were collecting freshwater crabs, which they singed on a smoldering log. Anyone in camp at that moment could tell you that trouble was in the air. In addition to the upcoming rapids with their ominous name, it turned out that 14 people had drowned in a flash flood at our camp two years ago. Also, the day before, a man had dropped a squashed, emaciated piglet off a hanging bridge in such a way that it splashed us as we floated past. Taking these events as bad signs, it was with some hesitation that I approached the rapids.

Instead of barreling right in, we pulled over to check out Dead Carabao, which added to the tension. The canyon tightened down, forming a series of steep ledges punctuated by swirling deep pits with rocks. After an hour of watching Greg and Bridget scout the rapids and explain all the obstacles and travails to Anton, Jasper, and Benny, I started to think that a portage seemed perfectly reasonable. The term Class V didn’t really mean much to me, but this here was a real carabao killer.

Eventually it was decided that, screw it, we’d go. Greg wanted to take the oar boat with the gear through first. After that, everyone else would follow in the paddle boat. Contingency plans were made to cover any scenario save the river somehow drying up and leaving us stranded in a cloud of dust. Downstream, Bridget and Anton set up safety ropes should we roll, be hung up, or get knocked out. The Kalinga guys spent this preparatory time throwing small rocks at another rock, which they had placed on a large rock in the river.

Greg pulled into the current and wet his neck with river water for safe passage. Cindy adjusted her hat over her purple curls. We rode the river around a steep bend and then the sound of the falling water hit, reminding me of the noise made by a massive car wreck. The current carried us smoothly to the first big ledge before it tripped over its own feet and rolled into froth, spilling us forward. Waves crashed up in blinding walls like a snowplow arching slush off a roadway into our windshield, and we hurtled down into watery pits only to be spit upward. Then, very suddenly, I was hit with about a gallon of water up my nose, followed by deep relief: We were on smooth water, and Greg pulled onto shore.

Now everyone standing at the bottom of the run was totally jazzed to scramble back upstream and shoot the rapids with the paddle raft. Just when all the celebrations and high-fiving were winding down, Greg looked up and said, “What’s this?”

I looked upriver and saw our Kalinga escorts in the paddle raft, minus the paying customers, minus the raft’s captain, spinning uncontrollably. Jasper and Anton stared at the approaching raft like it was an oddly dressed woman walking down the street, but Greg and Bridget wore horrified expressions. The raft’s new pilots paddled with extraordinary nonchalance considering the situation. Then they weren’t paddling at all, because they had entered Dead Carabao, and it was all they could do to hang on. It didn’t seem like they had any particular line in mind, and their run was beautiful in a fatalistic sort of way. They failed to catch the back eddy at the end of the rapids, and they failed to even try grabbing the safety lines, so they ran the next rapids, too, and then finally pulled over on the wrong side of the river, way downstream.

Sound bites from the river bank included “Total cowboy move”…”Utter lack of respect”…”No concern for safety”…”They could have been injured”…”Does anyone here have any idea at all what in the fuck those two were doing?” I couldn’t help but sit down and laugh, thinking that just because we’re on the river doesn’t mean we’re not in the Philippines.

The Kalinga guys simply sat on a rock and looked at us, waiting. For a moment it seemed as if our expedition coalition might dissolve. Bridget wanted to give them the boot, but changed her mind. Instead, they got a hearty lecture from Anton, who translated Bridget’s tirade. We never learned why they hijacked the raft, but I think it was partly a demonstration. For centuries the Kalinga have fought off various nations—even their own country’s government—that wanted to come to this land and leave behind armed regiments, mines, dams, churches, and fleets of earthmoving equipment. I have a feeling that those two guys were just fighting off any notions we may have had about them being afraid of this rafting shit. After their scolding, they joined us in the raft with their helmets and life jackets back on, looking as happy to be in that boat as the minute we launched.

Downstream we encountered nearly all 895 species of Philippine butterflies. Later, we paddled a rapids where the river widened way out and spilled through its course on steps strewn with car-size boulders. For every yard we went forward we seemed to fall one, like we were riding an aquatic escalator. We camped that night on a dried oxbow, with the tents spread along what was once the junction of two torrents. High-water marks were still many feet above us. Considering the near-constant rain, I checked every few minutes for an approaching flash flood and weighed my risks of sleeping there against the more unknown risks of sleeping in the jungle. Considering the Philippines have 167 reptiles and 110 mammals, the oxbow won out.

Toward nightfall we all gathered around a big fire the Kalinga guides had magically built with thoroughly wet wood. As I swigged some champagne and chewed through a few dried and salted squid, I grappled with that age-old question: If I’m standing in front of a fire in a light rain, do I get drier or wetter? While I pondered this, Anton was pondering the future. “I hope you can all come back next year, when we finally get to run the upper Cagayan,” he said. “Things with the guerrillas will be cooled off by then.”

Dave, the actor, said, “I bet it’ll be done raining then, too, right?”

Everyone laughed.

But then Anton and Greg began setting some dates for the renewed exploratory trip, and I realized they were serious. Our last day on the river, the rapids thinned out and lost the flamboyance of the previous day, except on a long stretch known as The Playground. There the Chico whipped through a gorge and the center of the current rose up like the hackles on an angry dog. The raft rode along the crest, bucking a series of smaller waves, as if it might slide off to either side.

The word “boondocks” comes from the Philippine word for mountain, bundok. It struck me as funny that we could be coming out of the boondocks while we were still way up in the bundoks, if you know what I mean. The valley widened, there were more cultivated banana plants and coconut trees, and less raw jungle. Mudslides off agricultural plots had recently ripped down hillsides, leaving scars like dirt roads with abrupt beginnings and ends. In the middle of the river, a nude man was building a series of large, mysterious rock cairns on a gravel bar, and we gave each other weird looks as the raft passed.

One of the bends in the river eventually turned out to be the bend and there was our jeepney, an out-of-place hunk of chrome shining on a large bank of fist-size gravel, seemingly blasted back from some future century. The lowland drivers looked as tense as they had when they’d dropped us off. We deflated the rafts and loaded them on the roof. Everyone jumped in and I sprawled out on a very comfortable pile of life jackets. The Kalinga guys waved goodbye. They were headed in a much different direction. Then the jeepney swung downhill, lurching along and dodging chickens.

Outfitter: Mukuni Wilderness Whitewater Expeditions, 800-235-3085; Dates: Cagayan River trips will run January 16- February 3 and February 6-24. Cost: $2,750-$3,150 per person (excluding airfare), which includes eight days of rafting, four days of sea kayaking, and two days of trekking