I’M TALKING TO Pavlo the Sailor in a back-alley Piraeus café, where mustached old men sip Greek coffee each morning under blueing Titanic posters and generic wall murals of the Acropolis. It’s two days before I’m scheduled to sail the Greek islands, and this has proven my favorite way to kill time in Athens’s old industrial port town. The harbor sits just three blocks away, and apart from the café, every shop in the alley sells buoys, rope, or life preservers.

sailing the Greek Isles

sailing the Greek Isles

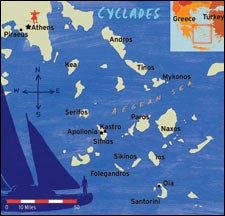

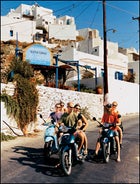

GRECIAN FORMULA: Motoring around on the island of Sifnos; below, scenes from the Cyclades.

GRECIAN FORMULA: Motoring around on the island of Sifnos; below, scenes from the Cyclades.sailing the Greek Isles

sailing the Greek Isles

ODYSSEAN DISTRACTIONS: The village of Oia, on Santorini; right, Swimming in Santorini's sunken caldera.

ODYSSEAN DISTRACTIONS: The village of Oia, on Santorini; right, Swimming in Santorini's sunken caldera.sailing the Greek Isles

Though he tells me he has plenty of experience at sea, Pavlo doesn’t look much like a sailor: no wool cap, no bristly beard, no faded tattoos. His appearance is closer to that of a scientist: slight of build, clean-shaven, with graying hair and an intense gaze. When I tell him about my plans, he nods approvingly and lights a Marlboro. “If you’re going to write an article about sailing in Greece,” he says, “you must mention Odysseus.”

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

“I don’t want to write about myths,” I tell him. “I want to see the Greek islands as they are today. Besides, Odysseus sailed to Ithaca; I’ll be sailing in the Cyclades.”

Pavlo puffs on his cigarette and thinks this over carefully. “I have seen the Cyclades many times,” he says. “Each visit to each island depends on when you go, who you go with, and how long you stay.”

“Exactly,” I say. “It’s subjective. That’s why Odysseus has nothing to do with me.”

“Ah, but you’re wrong.” Pavlo’s eyes glitter through a cloud of smoke. “That’s why Odysseus has everything to do with you.”

THREE DAYS later I find myself in eight-foot seas off the coast of Serifos Island, trying not to vomit as I wrap the mainsheet onto the winch of a 55-foot sailboat. The boat’s skipper, an unflappable 34-year-old Californian named Max Fancher, comes over to assess my work. “You almost got it,” he says diplomatically. “Only you should probably wrap it clockwise instead of counterclockwise, since the winch only goes in one direction.”

Nodding at my own mistakea blatant flub, akin to putting on underwear over the outside of my pantsI unwrap the winch and start over.

In spite of my seasickness and nautical ineptitude, I’m happy to be sailing into the heart of the Cycladesa stunningly beautiful archipelago of some 30 major islands southeast of the Greek mainland in the Aegean. Indeed, when most people envision the Greek islands,

The only problem is that I know very little about sailingwhich is why I’ve joined an eight-boat flotilla organized by Berkeley-based OCSC Sailing. Our goal for the next two weeks is to island-hop through the Cyclades to the gorgeous volcanic crescent of Santorini, then loop our way back to Athensa journey of 300 nautical miles. Some of the 46 sailors in our flotilla are folks who’ve trained for months on San Francisco Bay specifically for this kind of experience; others, like Gar Duke and Nicole Friend, at the helm of the Dafne, are sharpening their skills in anticipation of buying their own boat and sailing it around the world.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

My boat, the Assos, consists of Captain Max, his fiancée, Maggie Holmes, a first mate, a photographer, and five female novices ranging in age from 25 to 36. Like me, my fellow novices have come here to mix a hands-on vacation in the Greek islands with informal sailing instruction. Unlike the lessons OCSC offers on San Francisco Bay, this experience does not involve book study or comprehensive training. Rather, those who want to get a taste of sailing are invited to learn the ropes (which, Max informs me, are called lines) by helping with the day-to-day operation of the boat.

Amid the learning, Max continually reminds us we’re on vacation, and the atmosphere on board the Assos is fun and relaxed. Most of my boatmates are friends of Maggie’s, and they all share her insouciant intelligence, a predilection for wearing bikinis, and the tendency to giggle whenever they hear the name Assos. I have a boyish crush on every one of them, despite the fact that most of them have thrown up at least once today.

Rewrapping the sheet, I grind the winch and adjust the mainsail. The Assos pitches in the waves and sea spray whips across the cockpit. As we clear the lee of Serifos Island, the wind edges up past 25 knots and Captain Max decides our crew has had enough drama for one day. Sheeting in the sails, we motor across the channel to the island of Sifnos, where we moor for the night. We awake the following morning to angry whitecaps churning the channel and reports of 60-knot gusts along the 53-mile route to Santorini. Until these winds let up, Max tells us, we’ll be marooned on Sifnos.

COMPARED WITH THE MARQUEE islands of the CycladesSantorini, Ios, MykonosSifnos doesn’t have much of a reputation. According to Herodotus, the gold and silver mines on this 30-square-mile island made it the richest in the Aegean in the sixth century b.c. Two hundred years later, with its wealth exhausted, it collapsed into insignificance. Since then, Sifnos (pop. 2,500) has existed as a nondescript outpost, known more for its poets and pottery than politics or geography.

Despite the island’s lack of distinction, however, the Assos (as my boatmates and I have taken to calling one another) immediately fall in love with Sifnos. The tourist crowds have left with high season, and we have the island mostly to ourselves. Renting motorcycles, we cruise up intricately terraced valleys to the central plateau,

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

Our talk of winds and weather has given way to sunbathing and cliff diving, and we spend most of our time swimming in a turquoise cove under the cliffs of Kastro. As the sun sets, I stroke slowly along the cliff’s edge, disturbing schools of fish that dart beneath me through big beams of late-day sunlight. I flip over onto my back and watch butterflies skim the water as doves dart in the sky above. If the lotus eaters of Odysseus’s day had it any better than this, I’d be surprised.

After three blissfully indolent days on Sifnos, Captain Max reports that the winds have calmed; we raise anchor and our casual crash course in sailing resumes. As I practice tying soggy half hitches and sheet bends in a rainy stretch of sea near Folegandros Island, Max assures me that the willingness to make mistakes speeds the learning process. “Sometimes you learn best by just going out to sea and having things happen,” he says.

The more time I spend aboard the Assos, the more I appreciate the way sailing connects me to the rhythms of the weather and the water. Away from land, moment-by-moment life is less of an abstraction, and the sea gradually reveals itself as an intricate and powerful wilderness. Moreover, I’m discovering that so many of the metaphors one uses to describe life on land originated from the rituals of the sea. Many timeswhen asking if we’re “making headway,” for instance, or offering to “batten down the hatches”I find myself using correct sailing terminology entirely by accident. With each day at sea, through trial and error, I get more and more comfortable with my role on the boat.

TWO DAYS OUT OF SIFNOS, the rain clears and we sail into the caldera of Santorini under brilliant blue skies. Often associated with the lost city of Atlantis, this caldera dates back to around 1500 b.c., when one of the biggest volcanic eruptions in recorded history collapsed the middle of the island and sent deadly tidal waves surging out across the eastern Mediterranean. More than 3,500 years later, the dramatic, red-veined cliffs that rim the caldera are studded with elegant churches, flagstone paths, and pastel-hued houses. It’s a singularly gorgeous sight, and we trim in our sails and drift around the 32-square-mile caldera to take it all in.

Later, when my boatmates and I dinghy in to the Santorini shore, we discover an island snarled with rental-car traffic jams, high-tension power lines, and billboards for places like Señor Zorba’s Mexican Restaurant. After the sleepy anonymity we enjoyed on Sifnos, this comes as a letdown.

We make our way to the clifftop village of Oia, which proves more authentic, with its twisting alleyways, cave houses, and grand Orthodox churches, though visitors from places like Houston, Helsinki, and Hong Kong easily outnumber the 500 or so locals. The time-honored tradition here is to photograph the sunset as it glitters over the waters of the caldera below, and the crew of the Assos is not to be left out. Brandishing our digital cameras, we position ourselves among hundreds of fellow tourists at cliffside, each of us trying to catch the perfect angle of sunlight on the whitewashed mansions and church domeswithout getting one another’s arms and heads and cameras in the frame.

Of course, Santorini isn’t the goal of our flotilla as much as a pivot point. After two nights anchored off the volcanic crescent, we begin our journey back to Athens.

As we follow the winds home, each new island yields humble discoveries. On Sikinos, I dine on wild rabbit and hike at night under the stars; in the marble-studded mountains of Naxos, I talk politics and drink Nescafé with Greek shepherds; on Paros, I eat ice cream along the harbor while a film crew shoots scenes for a Greek soap opera. Not the stuff of Odysseus, perhaps, but I find charm in the buzz of each little adventure.

On our final day at seathe 39-mile leg from Kea to Marina Alimos, outside Athensa pod of dolphins begins to flirt off our port bow. We fire up the engine and weave along with the gray creatures for the good part of an hour before running out of fuel. In an instant, the dolphins are gone and the Assos is left bobbing off the Greek coast.

We have only a hint of wind for our sailsand the port is still more than ten miles awayso Captain Max has us haul out a colorful spinnaker. With two weeks of experience behind us, we rig the downwind sail with cheerful efficiency.

For a moment, we roll with the waves as the spinnaker hangs limp at the bow. Then a slight breeze billows the sail, and we witness a phenomenon as elemental and bewitching as a bolt of lightning or a spark of fire: Wind and boat connect, lines go tight, and we surge forward.

As we slowly float toward Athens, I again think back to Pavlo the Sailor. Nearly 100 years ago, the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy also used the example of Odysseus to downplay the importance of one’s final destination. To paraphrase his poem “Ithaca”: Don’t expect Ithaca to give you riches. It has already given you this journey.

THE GREECE FLOTILLA was organized by Berkeley-based OCSC Sailing (800-223-2984, ), with boats chartered from the Moorings. In addition to offering vacations, OCSC Sailing runs a school that offers a wide range of courses and activities for all skill levels. Lessons fulfill the requirements of the U.S. Sailing certification system, feature a low student-teacher ratio (three students to one teacher is the maximum), and take place in the scenic and challenging conditions of San Francisco Bay. Flotilla sailing is a great hands-on alternative to traditional cruising, and OCSC Sailing can accommodate novices, in addition to those qualified to skipper and crew their own charter boat. Prices are approximate, since final rates depend on the size of boat, quality of boat, and number of participants. All flotillas run between $150 and $200 per person per day. The prices for Caribbean and South Pacific flotillas include meals, which are not included for Mediterranean flotillas (since great restaurants abound onshore). The Tahiti and Croatia trips do not include hotels (many people sleep exclusively on the boats); and international flights are not included with any of the following trips. 2006 OCSC SAILING SCHEDULE:

Tahiti, July 2030; $1,800 per person (based on six people per boat); Croatia, September 923; $2,200 per person (based on six people per boat); Turkey, June 1025; Multisport ���ϳԹ���, $3,500 per person. BOOKS:

The Rough Guide to the Greek Islands ($22) proved to be the most detailed and useful for the Cyclades. Lonely Planet’s Greek Islands ($22) is a dependable (if less detailed) guide. DK Eyewitness Travel Guides’ The Greek Islands ($25) has terrific photos and illustrations to whet one’s appetite for a Cyclades sojourn.